Zarrinnaal

Zarrinnaal or Zarrin Naal (Persian: زرين نعل) is the name of a dynasty of Persian-Kurdish tribal chiefs and state officials belonging to the Zarrin Kafsh tribe and originated from Sanandaj in the Iranian Kurdistan Province. Their heads with the title of Beyg, Beyk or Beg (lit."lord") were the Aghas of Senneh ("Masters of Sanandaj") and ruled their fiefdom during the time of four hundred years when the Safavids (r. 1501-1722), Afsharids (r. 1736–1796) and finally Qajar dynasty (r. 1785–1925) reigned in Iran.[1]

Origin and meaning of the name

About the origin of the name "Zarrinnaal" various stories are told:

One says the family's ancestor rode in a battle against a foreign power a horse with golden horseshoes (Persian Zarrin Naal) and therefore was named after.[2]

Another says that this ancestor was sent as Persia's envoy to the Mughal Empire for border negotiations with the Indians. To show his wealth on this special ceremonial occasion and to convince his partners to agree, he once put golden horseshoes on his horse. When he took a ride the animal lost its horseshoes, people picked them up and so forth nicknamed him Zarrinnaal.[3] This also reports M. Lesan ol-Molk in his historical chronicle.[4] In fact there was a certain Mohammad Ali Beyg sent as ambassador to the Mughal court by Shah Abbas!

A third story tells us that this ancestor wanted to marry a shah's daughter but the king denied to give him his daughter's hand. Thus, he rode on a horse with golden horseshoes to impress the king and finally could pick up his bride.[5]

However, after this man his entire clan was called in the very same way and his descendents were entitled "Zarrinnaal" in honour to that forefather.

In fact the term naal or to be more precise na'al (نعل) means in modern Persian of today "horseshoe", but also is Nominative Singular of the Arab word na'eleyn meaning "shoes, slippers",[6] and was the common term for slippers. So, like Zarrinkafsh the term Zarrinnaal means "Golden Shoe" as well, but in a more elaborated Arabized way often used in former times and especially among the Kurds.

Tribal heads and their history

When the Persian shahs conquered their empire and established their supremacy over the western Kurdish principalities the Zarrinnaal family began to reach local prominence in Kurdistan. Its members were installed in military and administrative posts and aided the Ardalan rulers (r. 1187 to 1867) in governing their province.[7]

Mohammad Ali Beyg Zarrinnaal

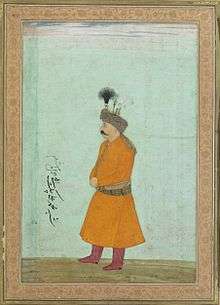

Mohammad Ali Beyg called Zarrinnaal (lit. "Golden Horseshoe"), whose family belonged to the clan of Zarrin Kafsh, had been settled in Kurdistan minimum since the year 1448 A.D. and possessed the area of Sanandaj as their hereditary fief, was ordered by Shah Abbas I the Great to make war on the Ottomans; and on August 24, 1605 with the aid of his troops from the Mokri tribes could reconquer the Turkish occupied Kurdistan Province for Persia. After that he was made vicegerent (Persian vali) of that area and reigned probably from 1609 to 1615 as governor and was head of the administration and army, chief judge and legislator. There, he himself and his entire tribal confederacy (Persian il) were known and henceforth called by the name of "Zarrinnaal".[8] In 1631 Mohammad ‘Ali Beyg was the ambassador sent to the Mughal court by Shah Abbas of Iran, arriving in time for the New Year festival in March 1631. Iran and Mughal India went in negotiations about the province of Kandahar, once part of the Mughal empire, then given by Humayoun to Shah Tahmasp and annexed by Humayoun's successor Akbar. In 1622 Shah Abbas had reconquered Kandahar as his rightly possession and a treaty with Jahangir should secure this status quo. Mohammad Ali Beyg remained in the Mughal empire until October 1632, during which time his portrait was painted by the royal artist, Hashim. The painting is inscribed in Persian ‘Likeness of Mohammad ‘Ali Beyg, ambassador, the work of Hashim’.

Mohammad Zaman Beyg

Mohammad Ali Beyg's son Mohammad Zaman Beyg was a merchant and traveller.[9] After Shah Abbas I's death in 1629 the Ottoman vizier Khusrew Pasha attacked the Kurdistan Province in 1634 and destroyed its capital city of Hassanabad. But next to it Sehna or Senneh, the modern city of Sanandaj was built as new residence and capital for the Ardalan emirs by Vali Soleyman Khan Ardalan (r. 1636 to 1657). Thus, the entire Kurdish tribal elite moved to the new capital of Sanandaj, which became a prosperous city. Thereby the name of Sanandaj comes from the Kurdish terms Sena meaning "soltan" or "ruler" and Daj (or Dezh) meaning "fortress", and thus means "The Ruler's Fortress", which refers to the Vali's stony fort on top of the city peak Teppeh-ye Painshahr (Teppeh-ye Tous-Nowzar).[10] In 1638 the common modern Turkish-Persian border was established at the foot of the Zagros Mountains between Mesopotamia and the Iranian Plateau.

Mahmoud Beyg Soltan

Mohammad Zaman Beyg's son Mahmoud Beyg Soltan was army captain and provincial sub-governor (soltan).[11] In Safavid time the military aristocracy of the emirs was divided in the three ranks of khan (i.e. "magnate", title of military commander), beyg (i.e. "lord", title of tribal chief) and soltan (i.e. "ruler", title of provincial sub-governor).

Mohammad Beyg

Mahmoud Beyg Soltan's son Mohammad Beyg was vicegerent (vali) of the Afghans (i.e. Pashtuns) after he was deputy governor (nayeb-e vali) in today's Afghanistan.[12] The province of Afghan with its capital of Kandahar belonged to the Safavid Empire until 1709.

Hajji Eskandar Beyg-e Afghan

Mohammad Beyg's son Hajji Eskandar Beyg-e Afghan was a leader of the Afghans (Persian beyg-e afghan) and after his arrival in the Kurdistan Province from a pilgrimage to the Holy City of Mecca he settled there again at Sanandaj.[13] In 1709 Ghilzai-Afghan rebels under their chief Mirwais Khan Hotak rose against the Persians, killed the Safavid governor of Kandahar, the Georgin Gurgin Khan (King George XI of Kartli), they declared their independence and finally caused the downfall of the Safavids when they seized and at last sacked the Safavid capital city of Isfahan in 1722.

Abbas Beyg Vazir

Hajji Eskandar Beyg's son Abbas Beyg was vizier of Persia (vazir-e Iran), had issued 18 children and was the head of his tribe (Persian ra'is-e il).[14] He served under Nader Shah Afshar (r. 1736–1747), who reinstated the Persian monarchy but was a brutal tyrant too, and was murdered by his own emirs in 1747. The Afshar and Qajar emirs allied with one of the shah's envoy and minister, Hossein Ali Beyg Bastami, while on a campaign entered the ruler's tent and cut off his head and also killed his two other ministers, Bader Khan and Abbas Beyg Vazir.

Oghli Beyg I.

Abbas Beyg's son Oghli Beyg I. was landlord (Persian mallak) of a big estate in the Kurdistan Province under the Valis of Ardalan.[15]

Ali Beyg Monshi-bashi

Oghli Beyg's son Ali Beyg Monshi-bashi was in the year 1799 chancellor and chief secretary (Persian monshi-bashi) of Vali Amanollah Khan Ardalan I (r. 1797–1825), one of the most powerful and popular rulers of Kordestān.[16] Responsible for the army's administration and Amanollah Khan's military power he was one of the chief ministers of the Ardalans,[17] and his family was described by Malcom as "one of the first principal families at the Ardalan court."[18] Finally Ali Beyg was killed 1826 at the battle of Mossul by Ottoman troops.[19]

Oghli Beyg II. Monshi

Ali Beyg's son Oghli Beyg II. Monshi was landlord and, like his father, ministerial (monshi) of the Valis of Ardalan in army service. After he quit service for the Ardalans (Khosrau Khan, r. 1825-1834; Reza Qoli Khan, r. 1834–1860, and Amanollah Khan II., r. 1860–1867) in the last years of his life he only looked after his estates in Kurdistan.[20]

Khosrau Khan followed his father Amanollah Khan I. but died young when poisoned by the orders of his father-in-law Fath Ali Shah Qajar. His two sons struggled for power over their father's domains, fought against each other and a civil war broke out until Nasser al-Din Shah Qajar deposed Reza Qoli Khan and terminated the Ardalan rule after Amanollah Khan's II. death.

Like most of all Kurds Oghli Beyg II. was a Sunni Muslim but for political reasons converted to the Shiite faith of Islam, the main religion in the Persian Empire. Oghli Beyg wanted to join his own family with the new established Qajar dynasty by marriage, and asked for the hand of Princess Noor-Jahan Khanom, the 9th daughter of Crown Prince Abbas Mirza Nayeb as-Saltaneh.[21]

When the young bride died Oghli Beyg married Noor-Jahan Khanom II. ("Noorjan Khanom") Ardalan, a daughter of Vali Amanollah Khan Ardalan, sister to Khosrau Khan and aunt to Reza Qoli and Amanollah II.[22]

Agha Mirza Zaman Khan Kordestani Lashkar-nevis (1842–1906)

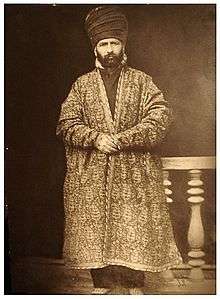

Oghli Beyg's son Agha Mirza Zaman Khan Kordestani Lashkar-nevis was muster-master (lashkar-nevis) of the Persian troops.[23]

Mirza Zaman Khan was born in Sanandaj by Noor Jahan Khanom at the Khosrau-Abad residential palace in 1842 and died at Tehran 1906. Himself from a family of Ardalan court grandees, responsible for army supplies, he got an extensive education in Arabic, literature, calligraphy and arithmetic.

On July 1, 1859 young Master Zaman joined the Shah's camp when Nasser al-Din Shah visited with his entourage the Kurdistan Province on a royal tour and stayed in its capital town of Sanandaj for three days. He entered the royal tent, paid obedience to the Shah and offered his service. Because the Vali of Kurdistan was not able to satisfied the wishes of the Shah's retinue and several of them were getting angry, the court departed from Kurdestan taking young Zaman with it. Via Tabriz and Maragheh he then moved to Tehran and reached the capital on October 19, 1859.[24] In 1867 Nasser al-Din Shah Qajar finally terminated the Ardalan rule in Kurdistan by deposing the last Vali and removing him with his own uncle Prince Farhad Mirza Mo'tamad ad-Dowleh as governor of the Kurdistan Province. Zaman settled then permanently in Tehran, moving from the Ark district to that of Oudlajan in the city's north-eastern part where the nobility had its residences and founded in 1868 a family.

Some samples of his handwriting convinced his superiors at court to give him an employment at the imperial court offices and so he became a bureaucrat in the governmental administration. His career started there as a clerk (Persian Mirza) and he was in charge of fiscal duties of the government, administration and military, responsible for the Kurdistan Province in special.

In 1872 with the improvements of Prime Minister Mirza Hossein Khan Moshir ad-Dowleh Mirza Zaman worked for the Ministry of War, and finally got the post of lashkar-nevis (lit. "army scribe", i.e. muster-master), who was chief paymaster of the troops and head of military administration. Until 1904 he worked in this office which became the hereditary post in his family for three generations and documented all costs and vouchers of payment of the entire soldiery of 200,000 men of that time. Mirza Zaman was honorary called Agha (lit. "Sir") by Nasser al-Din Shah and the former tribal title of Beyg, used in the family’s past, changed in that of a superior Khan ("magnate"), according to common Persian customs of calling landowners of old provenance with this not only hereditary but also adoptive sobriquet.[25] He then also became vizier of Kurdistan and finally governor of that Persian province.[26]

Furthermore, Agha Mirza Zaman Khan became military adviser to the Shah, and wrote books about military history and astronomy, also.

In 1867 Agha Mirza Zaman Khan Kordestani married Pari Soltan Khanom Pir-Bastami Zarrin Khanom ("Golden Lady"), daughter of Mohammad Hossein Khan Bastami (Moayyeri) Mir Panj and by Effat ad-Dowleh Khanom Qajar, and hence granddaughter in paternal line of Doust Ali Khan Moayyer al-Mamalek and in maternal line related to the Qajar dynasty. They had three children:

- Agha Mirza Ali Akbar Khan Zarrinnaal Lashkar-nevis Nasr-e Lashkar, the father of the future Zarrinnaal family

- Mirza Ali Asghar Khan Zarrinkafsh, the father of the future Zarrinkafsh family

- Banou Fatemeh Soltan Khanom Afshartous, the mother of the Afshartous family and General Mahmoud Afshartous in particular

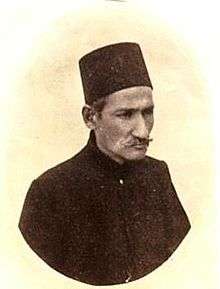

Agha Mirza Ali Akbar Khan Nasr-e Lashkar (1868–1930)

Agha Mirza Zaman Khan Kordestani's eldest was Agha Mirza Ali Akbar Khan Zarrinnaal, entitled for his merits in military sector with the aristocratic title Nasr-e Lashkar (lit. "Defender of the Army") by the Shah. He was born in 1868 at Tehran and died there 1930 on his estates at Doshan-Teppeh in eastern Tehran. He got a private education in writing, arithmetic and reading and in fencing, poetry, hunting, horsing and calligraphy and then he started military service. At the Tehran military academy (madresseh-ye nezam-e dowlati) he studied weapons technology and martial law. After his studies he entered service at court and became, like his father, military adviser to Nasser al-Din Shah and was also honorarily called Agha. Firstly he became lashkar-nevis and chief secretary of the army 1904 to 1906. Until the end of the Qajar rule 1925 he held several posts as head of the military administration, especially in the Army Law Court Department (majles-e mohakemat-e vezarat-e askari) of the Ministry of War (vezarat-e jang). Under Mozaffar ad-Din Shah Qajar (r. 1896–1906) and Mohammad Ali Shah Qajar (r. 1906–1909) he was military instructor to the Persian troops 1906 to 1909 and after that host inspector with the military rank of a nazem 1909 to 1915. As well, at the time of Mohammad Ali Shah he became conservative member of parliament (majles). With the nickname "Kordi" he was a delegate for Kurdistan and one leader of the royalist conservative wing (etedahiyun), supporting Mohammad Ali Shah's efforts to return to absolutism, because both men feared that the British dominated parliament could strengthen more English influence in Persia during the Great Game. In the reign of Ahmad Shah Qajar (r. 1909–1925) he was senior public prosecutor at martial court (moddai ol-omum koll-e nezam), which was instituted 1915 by Prince Abdol-Hossein Mirza Farmanfarma as minister of justice and war 1915 to 1925.[27]

For his loyal service to the Qajars he got parts of Nasser al-Din Shah's imperial hunting area east of Tehran, called Doshan-Teppeh. This sandy area became the base for the family, when it was cultivated in the days of Reza Shah Pahlavi by Nasr-e Lashkar's sons and villas and summer residences of Tehran's court elite were built there, naming it "Zarrinnaal-District" (mahalleh-ye zarrinnaal). It was situated next to Meydan-e Baharestan (Baharestan-Square) with the Parliament Building (called Baharestan lit. "Place of Springtime") directly behind the old Shemiran-Gate, at a quarter between the Khiyaban-e Baharestan and Khiyaban-e Mazanderan, Khiyaban-e Vahid Dastgerdi and Khiyaban-e Jaleh (today Khiyaban-e Mojaheddin-e Eslam). The two main streets were the Khiyaban-e Zarrinnaal ("Avenue Zarrinnaal" today Khiyaban-e Shahid Homayoun Nateqi) and Khiyaban-e Khorshid ("Avenue Khorshid" today Khiyaban-e Shahid Meshki).[28]

Agha Mirza Ali Akbar Khan Nasr-e Lashkar was married four times and had ten children, seven sons and three daughters:

- a. 1883, Marziyeh Khanom, called "Massoumeh" (d. 1893), mother of

- Mohammad Ali Khan Zarrinnaal Lashkar-nevis III Nasir on-Nezam (b. 1884)

- b. 1893 Roghiyeh Khanom Vali (1876–1910), his chief wife, elder daughter of Mohammad Khan Vali of Yazd by Mehr-e Jahan Khanom (Bibi Hajjar), his second cousin and mother of

- (Ali) Javad Khan Zarrinnaal (b. 1894)

- (Ali) Kazem Khan Zarrinnaal (b. 1896), who named himself Zarrinkafsch after his uncle, 1944.

- (Ali) Davood Khan Zarrinnaal (b. 1899)

- (Ali) Jafar Khan Zarrinnaal (b. 1900)

- (Ali) Mehdi Khan Zarrinnaal (b. 1902)

- (Ali) Ahmad Khan Zarrinnaal (b. 1904)

- Talat al-Molouk Khanom Zarrinnaal (b. 1898)

- c. 1910, Ameneh Khanom Vali (1880–1913), Roghieyeh's younger full sister and mother of

- Zarrin-Malek Khanom Zarrinnaal, called "Malek-Taj" (b. 1911)

- d. 1913, Nayereh Khanom Zarrinnaal, mother of

- Sakineh Zarrin-Homa Khanom Zarrinnaal (b. 1913)

Relations of the Zarrinnaals to the Ardalan family

The relations of the family with the Ardalan dynasty which ruled main parts of Kurdistan which today forms the Iranian Kurdistan Province as princes and hereditary governor-generals until 1867 are various:

- Shah Abbas appointed Mohammad Ali Beyg Zarrinnaal as Vali of Kurdistan as a counterpart to the Ardalan princes.

- Vali Soleyman Khan Ardalan chose 1634 the old Zarrin Kafsh fiefdom of Senneh (Sanandaj), the Zarrinnaal's original hometown, as his new capital.

- When after the Afghan debacle 1709–1720 the Zarrinnaal Hajji Eskandar Beyg-e Afghan came back to Kurdistan, his family again settled in Sanandaj and became prominent members of the Ardalan princely court especially with Vazir Abbas Beyg Rais-e Il, chief of that very tribe which ruled the whole area for centuries, Oghli Beyg as big landlord, Ali Beyg Monshi-bashi (1770–1826), and Oghli Beyg Zarrinnaal II Monshi (1808–1868) as hereditary chief secretaries to the Ardalan governors.

- Oghli Beyg II married Noor-Jahan ("Noorjan") Khanom, daughter of Vali Amanollah Khan Ardalan I.

- Their daughter Zarrin-Taj Khanom (1860–1884) married her cousin Abol Hassan Khan Ardalan Fakhr ol-Molk (1862–1926) as his first wife and was the mother of Gholam Reza Khan Ardalan Fakhr ol-Mamalek.[29] While their son Agha Mirza Zaman Khan Kordestani left Sanandaj for Tehran to make his career at the Qajar Imperial court of Nasser al-Din Shah.

References

- ↑ Zarrinkafsch: "Transition of Tribal Nobility to Urban Elite", in: Qajar Studies, Vol. VIII, 2008, p. 97 ff.; see also: The Zarrinkafsch (Bahman-Qajar) Webpage http://www.zarrinkafsch-bahman.org

- ↑ Oral tradition by Ahmad Khan Zarrinnaal.

- ↑ Oral tradition by Kazem Khan Zarrinnaal.

- ↑ Lesan ol-Molk: Nasekh at-Tawarikh, Vol. 3, p. 439.

- ↑ Oral tradition by Sakineh Zarrinnaal and Manijeh Vali.

- ↑ Junker/Alavi: Farhang-e Farsi Almani, 2002, p. 808.

- ↑ Zarrinnaal: Surat-e asāmi-ye ağād-e pedari-ye Zarrinna‘al, 1967, no. 1–11.

- ↑ Zarrinnaal: Surat-e asāmi-ye ağād-e pedari-ye Zarrinna‘al, 1967, no. 11.

- ↑ Zarrinnaal: Surat-e asāmi-ye ağād-e pedari-ye Zarrinna‘al, 1967, no. 10.

- ↑ Ayazi: A'iney'-ye Sanandaj, 1981, p. 31; Ardalan: Les Kurdes d'Ardalan, 2004, p. 40, fn. 112; see also: Zarrin Kafsh.

- ↑ Zarrinnaal: Surat-e asāmi-ye ağād-e pedari-ye Zarrinna‘al, 1967, no. 9.

- ↑ Zarrinnaal: Surat-e asāmi-ye ağād-e pedari-ye Zarrinna‘al, 1967, no. 8.

- ↑ Zarrinnaal: Surat-e asāmi-ye ağād-e pedari-ye Zarrinna‘al, 1967, no. 7.

- ↑ Zarrinnaal: Surat-e asāmi-ye ağād-e pedari-ye Zarrinna‘al, 1967, no. 6.

- ↑ Zarrinnaal: Surat-e asāmi-ye ağād-e pedari-ye Zarrinna‘al, 1967, no. 5.

- ↑ Zarrinnaal: Surat-e asāmi-ye ağād-e pedari-ye Zarrinna‘al, 1967, no. 4.

- ↑ A. Kordestani: Tarikh-e Mardukh, 1944, p. 106; M. Kordestani: Tarikh-e Ardalan, 1946, pp. 43–47.

- ↑ Malcom: Sketches, II, 1845, p. 277.

- ↑ Bruinessen: Agha, Scheich und Staat, 1989, p. 92 ff.

- ↑ Zarrinnaal: Surat-e asāmi-ye ağād-e pedari-ye Zarrinna‘al, 1967, no. 3; see also: A. Kordestani, 1944, p. 106 and M. Kordestani, 1946, pp. 43–46.

- ↑ Buyers: "The Qajar Dynasty", 2001, p. 8/qajar5.

- ↑ Barjesteh: "The Fath Ali Shah Project", in: Qajar Studies, Vol. IV, 2004, p. 175.

- ↑ Zarrinnaal: Surat-e asāmi-ye ağād-e pedari-ye Zarrinna‘al, 1967, no. 2.

- ↑ Busse: History of Persia under Qajar Rule, 1972, p. 341; Mostofi: Administration and Social History, 1995, I, p. 60.

- ↑ Migeod: Die persische Gesellschaft unter Nasirud Din Schah, 1990, p. 54.

- ↑ Barjesteh: "The Afshartous (Qajar-Quvanlu) Family", 2010, p. 215.

- ↑ Floor: "Change and Development in the Judicial System of Qajar Iran", 1992, p. 144, fn. 67.

- ↑ See: Tehran. A Tourist Guide, Geographical & Cartographical Institute Tehran, 2005.

- ↑ Mostofi Moghadam: "The Fath Ali Shah Project - the Descendants of Princess Hosn-e Jahan Khanoum Qajar: The Ardalan Family, Part 1", in: Qajar Studies, Vol VI, 2006, p. 191.

Literature

Ardalan, Shireen: Les Kurdes Ardalân, Geuthner, Paris 2004.

Ayazi, Burhan: A’ineh’-ye Sanandaj, Amir Kabir, Tehran 1360 (1981).

Barjesteh, Ferydoun: "The Fath Ali Shah Project" in: Qajar Studies. Journal of the IQSA, Vol IV and Vol X, Barjesteh van Waalwijk van Doorn & Co, Rotterdam 2004 and 2010.

Bruinessen, Martin M. van: Agha, Scheich und Staat, Edition Parabolis, Berlin 1989.

Busse, Heribert: History of Persia under Qājār Rule, transl. of Ḥasan-e Fasā'i's Fārsnāma-ye Nāṣeri, Columbia University Press, New York & London 1972.

Buyers, Christopher: "The Qajar Dynasty", in : Persia: A historical and genealogical view of the ruling dynasties of Persia in AD 1500-1979, Royal Ark, London 2001.

Floor, Willem: "Change and Development in the Judicial System of Qajar Iran (1800–.1925), in: Qajar Iran. Political, Social and Cultural Change 1800–1925, Mazda Publishers, Costa Mesa 1992.

Junker, Heinrich/Bozorg Alavi: Farhang-e Farsi Almani. Persisch-Deutsches Wörterbuch, Harrasowitz, Wiesbaden 2002.

Kordestani, Ayatollah Sheykh Mohammad Mardukh: Tarikh-e Mardukh, 2 Vols., Chapkhaneh Artesh, Tehran 1944.

Kordestani, Mah Sharaf Khanom: Tarikh-e Ardalan, Nasser Azadpour, Sanandaj 1946.

Lesan ol-Molk, Mirza Mohammad Taqi Sepehr: Nasekh at-Tawarikh, edit. I (3), Tehran 1377 (1998).

Malcom, Sir John: Sketches of Persia, 2 Vols., Murray, London 1845.

Migeod, Heinz-Georg: Die persische Gesellschaft unter Nasirud Din Schah (1848–1896), Klaus Schwarz Verlag, Berlin 1990.

Mostofi, Abdollah: The Administrative and Social History of the Qajar Period, Vol I, Mazda Publishers, Costa Mesa 1997.

Mostofi Moghadam, Houri/Nayer Mostofi Glenn and Mariam Moghadam Safinia: "The Fath Ali Shah Project - the Descendants of Princess Hosn-e Jahan Khanoum Qajar: The Ardalan Family, Part 1", in: Qajar Studies. Journal of the International Qajar Studies Association, Vol VI, Barjesteh van Waalwijk van Doorn & Co, Rotterdam 2006, pp. 189–249.

Tehran. A Tourist Guide, Geographical & Cartographical Institute Tehran, Tehran 2005.

Zarrinkafsch (Bahman-Qajar), Arian K.: "Transition from Tribal Nobility to Urban Elite: the Case of the Kurdish Zarrinnaal Family", in: Qajar Studies: Journal of International Qajar Studies Association, Vol. VIII, Barjesteh van Waalwijk van Doorn & Co, Rotterdam 2008, pp. 97–125.

Zarrinnaal, Jafar: Surat-e asāmi-ye ağād-e pedari-ye Zarrinna‘al, Tehran 1967.

Further reading

Zarrinkafsch (Bahman-Qajar), Arian K.: "Iranian Heraldry", in: Qajar Studies. Journal of the IQSA, Vol III, Barjesteh van Waalwijk van Doorn, Rotterdam 2003, pp. 9–31.

Zarrinkafsch (Bahman-Qajar), Arian K.: The Zarrinkafsch (Bahman-Qajar) Webpage, (March 2011).