Joseph in Islam

Islamic Prophets |

|---|

|

|

Listed by Islamic name and Biblical name. The six marked with a * are considered major prophets.

|

|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Islam |

|---|

|

|

Related topics |

|

Yūsuf ibn Yaʿqūb ibn Isḥāq ibn Ibrāhīm (Arabic: يوسف; estimated to have lived in the 16th century BCE [1]) is an Islamic prophet found in the Qurʾān, the scripture of Islam,[2] and corresponds to Joseph (son of Jacob), a character from the Jewish religious scripture, the Tanakh, and the Christian Bible. It is one of the common names in the Middle East and among Muslim nations. Of all of Jacob's children, Joseph was the one given the gift of prophecy. Although the narratives of other prophets are mentioned in various suras, the complete narrative of Joseph is given only in one sura, Yusuf, making it unique. It is said to be the most detailed narrative in the Qur'an and bears more details than the Biblical counterpart.[3]

Yusuf is believed to have been the eleventh son of Jacob (Yaʿqūb), and, according to many scholars, was his favorite. According to Ibn Kathir, “Jacob had twelve sons who were the eponymous ancestors of the tribes of the Israelites. The most noble, the most exalted, the greatest of them was Joseph."[4] The story begins with Joseph revealing a dream to his father, which Jacob recognizes as a vision.[5] In addition to the role of God in his life, the story of Yusuf and Zulaikha (Potiphar's wife of the Old Testament) became a popular subject in Persian literature, where it became considerably elaborated over the centuries.[6]

Historical narrative in Islam

The story of Joseph in the Qurʾān, a continuous narrative, is considered one of the most beautifully written suras. There are less than one hundred verses but they encompass many years and “present an amazing variety of sciences and characters in a tightly-knit plot, and offer a dramatic illustration of some of the fundamental themes of the Qurʾān."[7] The Qurʾān itself relates to us the importance of the story in the third verse: “and We narrate unto you the best (or most beautiful) of stories (aḥsan al-qeṣaṣ).” Most scholars believe this is referring to Joseph’s story, while others, including Ṭabari, argue it is a reference to the Qurʾān as a whole.[8] It documents the execution of God's rulings despite the challenge of human intervention ("And Allah hath full power and control over His affairs; but most among mankind know it not").[9]

This is what the story of Yūsuf (AS) confirms categorically, for it ends with comfort and marvels, which is described in Qurʾān. Along with the story there is also some commentary from some leading scholars of Islam.

Joseph before the dream

Muhammad Ṭabari provides exquisite detail and commentary of this narrative in his chapter on Joseph relaying the opinions of well-known scholars. In Ṭabari’s chapter, we are first introduced to the physical beauty of Joseph and his mother Rachel, in fact they are said to have had “more beauty than any other human being."[10] His father, Jacob, had given him to his oldest sister to be raised. Ṭabari comments that there was no greater love than what Joseph’s aunt felt for him as she had raised him as her own. And she was very reluctant to give him back to Jacob and kept him until her death. The reason, according to Ṭabari, that she was able to do this was because of a belt that had been passed to her from her father, Isaac. Ṭabari notes “if someone else acquired it by guile from the person who was supposed to have it, then he would become absolutely subject to the will of the rightful owner.”[11] This is important because Joseph’s aunt puts the belt on Joseph when Jacob is absent and then accuses Joseph of stealing it and he thus stays with her until her death. Jacob was very reluctant to give up Joseph and thus favors him when they are together. This is commentary but, as is the profession of commentators, this provides an interesting set up to Joseph’s personal story and also lays a foundation for a future interaction with his brothers, particularly Benjamin.

The dream

The story begins with a dream and ends with its interpretation. As the sun appeared over the horizon, bathing the earth in its morning glory, Joseph, son of Jacob awoke from his sleep, delighted by a pleasant dream he had. Filled with excitement he ran to his father and reported what he had seen.

Yusuf said to his father: "O my father! I did see eleven planets and the sun and the moon: I saw them prostrate themselves to me!"

According to Ibn Kathir, Jacob knew that Joseph would someday become extremely important and would be in a high position, both in this world and the next—he recognized that the planets represented his brothers and the sun and moon represented himself and Joseph’s mother, Rachel. Jacob advised Joseph to keep the dream to himself in order to protect him from the jealousy of his brothers, who were already unhappy about the love Jacob felt for Joseph.[13] Jacob foresaw that Yūsuf would be one through whom the prophecy of his grandfather, Ibrahim, would be fulfilled, in that his offspring would keep the light of Abraham's house alive and spread God's message to mankind. Abu Ya’ala interpreted Jacob’s reaction as an understanding that the planets, sun and moon bowing to Joseph representing “something dispersed which God united."[13] Jacob tells Joseph, "My son, relate not thy vision to thy brothers, lest they concoct a plot against thee: for Satan is a clear enemy to humanity. “Thus your Lord has selected you and given you knowledge to interpret reports, and has perfected his blessing upon you and upon the family of Jacob just as he perfected it on your forefathers before: Abraham and Isaac. Your Lord is Knowing, Wise” Qur'an, sura 12 (Yusuf) ayat 5-6[14]

Joseph did not tell his brothers his dream, unlike in the version relayed in the Hebrew Bible, but their dislike of him was already too strong to subdue. Ṭabari demonstrates this by adding that they said to each other, “verily Joseph and his brother (Benjamin) are dearer to our father than we are, though we may be a troop (‘usbah). By usbah they meant a group, for they were ten in number. They said, “Our father is plainly in a state of aberration."[15]

Joseph was known, in addition for being very handsome, to be of gentle temperament. He was respectful, kind and considerate. His brother Benjamin was equally pleasant and both were from the same mother, Rachel. From hadith:

Narrated Abu Huraira:

Some people asked the Prophet: "Who is the most honorable amongst the people?" He replied, "The most honorable among them is the one who is the most Allah-fearing." They said, "O Allah's Prophet! We do not ask about this." He said, "Then the most honorable person is Yusuf, Allah's Prophet, the son of Allah's Prophet, the son of Allah's Prophet, the son of Allah's Khalil.[16]"

The plot against Joseph

The Qurʾān continues with Joseph’s brothers plotting to kill him. It relates: “in Joseph and his brothers are signs for those who seek answers. When Joseph’s brother said about him: “He is more loved by our father than we are, and we are a group. Our father is in clear error. Let us kill Joseph or cast him to the ground, so that the face of your father will be toward you, and after him you will be a community of the truthful.” —|Qur'an, sura 12 (Yusuf) ayat 7-9.[18]

But one of the brothers argued against killing him and suggested they throw him into a well, said to be Jubb Yussef (Joseph's Well), so that a caravan might pick him up and take him into slavery. Mujahid, a scholar, says that it was Simeon and Suddi says it was Judah while Qatadah and Ibn Ishaq says that it was the eldest, Ruben.[19] Said one of them: "Slay not Joseph, but if ye must do something, throw him down to the bottom of the well: he will be picked up by some caravan of travellers."|Qur'an, sura 12 (Yusuf) ayah 10[20]

Killing Joseph because of jealousy is extreme but scholars also suggest that Joseph was fairly young when he was thrown into the well, as young as twelve. He would live to be 120.[21]

The brothers asked their father to let them take Joseph out to the desert to play and promised to watch him. Jacob, not thrilled with the idea knowing how much the brothers disliked Joseph, hesitated. Ṭabari comments that Jacobs’s excuse was that the wolves might hurt him.[22] But the brothers insisted. When they had Joseph alone they threw him into a well and left him there, They returned with a blood stained shirt and lied that he had been attacked by a wolf but their father did not believe them, as he was a sincere man who loved his son.[22]

As the verses say,

They said: "O our father! why dost thou not trust us with Joseph,- seeing we are indeed his sincere well-wishers?

Send him with us tomorrow to enjoy himself and play, and we shall take every care of him."

(Jacob) said: "Really it saddens me that ye should take him away: I fear lest the wolf should devour him while ye attend not to him."

They said: "If the wolf were to devour him while we are (so large) a party, then should we indeed (first) have perished ourselves!"

So they did take him away, and they all agreed to throw him down to the bottom of the well: and We put into his heart (this Message): 'Of a surety thou shalt (one day) tell them the truth of this their affair while they know (thee) not'

Then they came to their father in the early part of the night, weeping.

They said: "O our father! We went racing with one another, and left Joseph with our things; and the wolf devoured him.... But thou wilt never believe us even though we tell the truth."

They stained his shirt with false blood. He said: "Nay, but your minds have made up a tale (that may pass) with you, (for me) patience is most fitting: Against that which ye assert, it is Allah (alone) Whose help can be sought"..— Qur'an, sura 12 (Yusuf) ayat 11-18[23]

Ṭabari comments that Judah stopped the brothers from causing more harm to Joseph and would bring him food.[22] Ibn Kathir comments that Reuben suggested that they put him in the pit so that he might return later to bring him home. But when he returned, he found Joseph gone. “So he screamed and tore his clothes. He put blood on the coat of Joseph. When Jacob learned of this, he tore his clothes, wore a black cloak, and was sad for many days."[24] Ibn Abbas writes that the “reason for this trial of Jacob was that he had slaughtered a sheep while he was fasting. He asked a neighbor of his to eat it but he did not. So God tested him with the matter of Joseph."[25] The section that describes Joseph’s revelation in the well is interpreted by Ibn Abbas: “When they were unaware” (12:15) means “you will tell them about what they did in a situation in which they will not recognize you."[26] This is yet more foreshadowing. A possible reason for his enslavement was that after Abraham had left Egypt he took slaves with him but “Abraham did not dismount for them (following barefoot). “Therefore God revealed to him: “Since you did not alight for the slaves and those walking barefoot with you, I will punish you by selling one of your decedents into his country." [27]

God's plan to save Joseph

A passing caravan took Joseph. They had stopped by the well hoping to draw water to quench their thirst and saw the boy inside. So they retrieved him and sold him into slavery in Egypt, to a rich man referred to as 'Aziz[28] in the Qur'an or Potiphar in the Bible.[29] ʿAzīz is also known as Qatafir or Qittin.[30] Joseph was taken into ʿAzīz’s home who told his wife to treat him well.

Then there came a caravan of travellers: they sent their water-carrier (for water), and he let down his bucket (into the well)...He said: "Ah there! Good news! Here is a (fine) young man!" So they concealed him as a treasure. But Allah knoweth well all that they do.

The (Brethren) sold him for a miserable price, for a few dirhams counted out: in such low estimation did they hold him!

The man in Egypt who bought him, said to his wife: "Make his stay (among us) honourable: maybe he will bring us much good, or we shall adopt him as a son." Thus did We establish Joseph in the land, that We might teach him the interpretation of stories (and events). And Allah hath full power and control over His affairs; but most among mankind know it not.

When Joseph attained His full manhood, We gave him power and knowledge: thus do We reward those who do right.— Qur'an, sura 12 (Yusuf) ayat 19-22[31]

This is the point of the story that many scholars of Islam report as being central (contrasting to other religious traditions) to Joseph’s story. Under ʿAzīz Misr (“the mighty one of Egypt”), Joseph moves to a high position in his household. Later, the brothers would come to Egypt but would not recognize Joseph but called him by the same title, al-ʿAzīz.[32]

While working for 'Aziz, Joseph grew to be a man. He was constantly approached by 'Aziz's wife (Imra'at al-Aziz) (presumably Zulayka or Zuleika) (variations include Zulaykha and Zulaikha as well) who intended to seduce him. Tabari and others are not reticent to point out that Joseph was mutually attracted to her. Ṭabari writes that the reason he did not succumb to her was because when they were alone the “figure of Jacob appeared to him, standing in the house and biting his fingers…” and warned Joseph not to become involved with her. Ṭabari, again, says “God turned him away from his desire for evil by giving him a sign that he should not do it." [33] It is also said that after ʿAzīz’s death, Joseph married Zolayḵā.[32]

But she in whose house he was, sought to seduce him from his (true) self: she fastened the doors, and said: "Now come, thou (dear one)!" He said: "Allah forbid! truly (thy husband) is my lord! he made my sojourn agreeable! truly to no good come those who do wrong!"

And (with passion) did she desire him, and he would have desired her, but that he saw the evidence of his Lord: thus (did We order) that We might turn away from him (all) evil and shameful deeds: for he was one of Our servants, sincere and purified.— Qur'an, sura 12 (Yusuf) ayat 23-24[34]

Zolayḵā is said to have then ripped the back of Joseph's shirt and they raced with one another to the door where her husband was waiting. At that point she attempted to blame Joseph and suggested that he had attacked her. However, Joseph said that it was Zolayḵā who had attempted to seduce him and his account is confirmed by one of the household. 'ʿAzīz believed Joseph and told his wife to beg forgiveness." [35] One member of the family, it is disputed who (perhaps a cousin) told ʿAzīz to check the shirt. If it was torn in the front than Joseph was guilty and his wife innocent but if it was torn in the back, Joseph was innocent and his wife guilty. It was torn in the back so ʿAzīz reprimands his wife for lying.[36]

Zuleika's circle of friends thought that she was becoming infatuated with Joseph and mocked her for being in love with a slave. She invited them to her home and gave them all apples, and knives to peel them with. She then had Joseph walk through and distract the women who cut themselves with the knives. Zuleika then pointed out that she had to see Joseph every day.[36]

Joseph prayed to God and said that he would prefer prison to the things that Zolayḵā and her friends wanted. According to Ṭabari, some time later, even though ʿAzīz knew that Joseph was innocent, he “grew disgusted with himself for having let Joseph go free…It seemed good to them to imprison him for a time." [37] It is possible that Zolayḵā had influence here, rebuking her husband for having her honor threatened.

The account of Joseph and the wife of 'Aziz is called Yusuf and Zulaikha and has been told and retold countless times in many languages. The Qur'anic account differs from the Biblical version in which Potiphar believes his wife and throws Joseph into prison.[38]

Joseph interprets dreams

This account refers to the interaction between the prophet Joseph and the ruler of Egypt. Unlike the references to Pharaoh in the account of Moses, the account of Joseph refers to the Egyptian ruler as a "king", not a pharaoh. After Joseph had been imprisoned for a few years, God granted him the ability to interpret dreams, a power that made him popular amongst the prisoners. One event concerns two royal servants who, prior to Joseph's imprisonment, had been thrown into the dungeon for attempting to poison the food of the king – the name is not given either in the Qur'an or the Bible – and his family. Joseph asked them about the dreams they had, and one of them described that he saw himself pressing grapes into wine. The other one said that he had seen himself holding a basket of bread on his head and the birds were eating it. Joseph reminded the prisoners that his ability to interpret dreams was a favor from God based on his adherence to monotheism. Joseph then stated that one of the men (the one who dreamt of squeezing grapes for wine) would be released from the prison and serve the king but warned that the other would be executed, and so was done in time.[39]

Joseph had asked the one whom he knew would be released, and Ṭabari writes that his name was Nabu, to mention his case to the king. When asked about his time in prison, Ṭabari reports that the Prophet Muhammad said: “If Joseph had not said that—meaning what he said (to Nabu)—he would not have stayed in prison as long as he did because he sought deliverance from someone other than God." [40]

The king had a dream of seven fat cows being eaten by seven skinny ones and seven ears of corn being replaced with shriveled ones, and he was terrified. Unfortunately, none of his advisors could interpret it. When the servant who was released from prison heard about it, he remembered Joseph from prison and persuaded the king to send him to Joseph so that he could return with an interpretation. Joseph told the servant that Egypt would face seven years of prosperity and then suffer seven years of famine and that the king should prepare for it so as to avoid great suffering.[41]

Scholars debate as to whether Joseph agreed to interpret the dream right away or if he declared that his name should be cleared in the house of ʿAzīz first. Ṭabari notes that when the messenger came to Joseph and invited him to come to the king, Joseph replied “Go back to your lord and ask him about the case of the women who cut their hands. My lord surely knows their guile." [42] Ibn Kathir agrees with Ṭabari saying that Joseph sought “restitution for this in order that ʿAzīz might know that he was not false to him during his absent” and that Zolayḵā eventually confessed that nothing happened between them.[43] Ṭabari inserts an interesting interaction between Joseph and the angel Gabriel in which Gabriel helps Joseph both gain his freedom and admit to his own desires.[40]

Joseph said, "What you cultivate during the next seven years, when the time of harvest comes, leave the grains in their spikes, except for what you eat. After that, seven years of drought will come, which will consume most of what you stored for them. After that, a year will come that brings relief for the people, and they will, once again, press juice." (12:47-49) Joseph was brought to king and, after interpreting the dream, was given Egypt's warehouses to look after.[21]

The family reunion

Joseph became extremely powerful and eventually married Zolayḵā (multiple sources mention that she was actually still a virgin) and had two sons by her: Ephraim and Manasseh. Ibn Kathir relates that the king of Egypt had faith in Joseph and that the people loved and revered him. It is said that Joseph was 30 when he was summoned to the king. “The king addressed him in 70 languages, and each time Joseph answered him in that language." [43] Ibn Ishaq comments, “the king of Egypt converted to Islam at the hands of Joseph”.[41]

Joseph’s brothers, in the meantime, had suffered while the people of Egypt prospered under Joseph’s guidance. Jacob and his family were hungry and the brothers went to Egypt, unaware that Joseph was there and in such a high position.[44] Joseph gave them what they needed but questions them and they reveal that there were once twelve of them. They lie and say that the one most loved by their father, meaning Joseph, died in the desert. Joseph tells them to bring Benjamin, the youngest, to him. They return home to Jacob and persuade him to let Benjamin accompany them in order to secure food. Jacob insists that they bring Benjamin back—and this time the brothers are honest when they swear to it.[45] According to Ibn Kathir, Jacob ordered the brothers to use many gates when returning to Egypt because they were all handsome.[46] The Qurʾān itself elaborates that Jacob sensed Joseph.

When the brothers return with Benjamin, Joseph reveals himself to Benjamin. He then gives the brothers the supplies he promised but also put the kings cup into one of the bags. He then proceeds to accuse them of stealing, which the brothers deny. Joseph informs them that whoever it was who stole the cup will be enslaved to the owner and the brothers agree, not realizing the plot against them. Ṭabari reports that the cup was found in Benjamin’s sack.[47]

After much discussion and anger, the brothers try to get Benjamin released by offering themselves instead—for they must keep their promise to their father. Reuben stays behind with Benjamin in order to keep his promise to his father. When the other brothers inform Jacob of what has happened, Jacob does not believe them and becomes blind after crying much over the disappearance of his son. Forty years had passed since Joseph was taken from his father, and Jacob had held it in his heart. Jacob sends the brothers back to find out about Benjamin and Joseph. Upon their return Joseph reveals himself to his brothers and gives them one of his shirts to give to Jacob.[48] When Jacob receives the shirt, this time as good news, Jacob lays it on his face and regains his vision. He says “Did I not tell you that I know from God what you do not know?” (12:96). Ṭabari says that this means that “from the truth of the interpretation of Joseph’s dream in which he saw eleven planets and the sun and the moon bowing down to him, he knew that which they did not know." [49] Joseph was reunited with his family, and his dream as a child came true as he saw his parents and eleven of his brothers prostrating before him in love, welcome and respect. Ibn Kathir mentions that his mother had already died but there are some who argue that she came back to life.[50] Ṭabari says that she was alive. Joseph eventually died in Egypt. Tradition holds that when Musa (Moses) left Egypt, he took Joseph's coffin with him so that he would be buried alongside his ancestors in Canaan.[50]

Use of "king" vs. "pharaoh"

In the Qur'an, the title of the Ruler of Egypt during the time of Joseph is specifically said to be "king" whilst that of the Ruler of Egypt during the time of Moses is specifically said to be "pharaoh". This is interesting because according to historical sources, the title pharaoh only began to be used to refer to the rulers of Egypt (starting with the rule of Thutmose III) in 1479 BCE - approximately 21 years after the prophet Joseph died.[51] But in the narration of Yusuf in the Bible, the title pharaoh is used for both rulers of Egypt.

The king (of Egypt) said: "I do see (in a vision) seven fat kine, whom seven lean ones devour, and seven green ears of corn, and seven (others) withered. O ye chiefs! expound to me my vision, if it be that ye can interpret visions."

"Then after them We sent Mûsa (Moses) with Our Signs to Fir'aun (pharaoh) and his chiefs, but they wrongfully rejected them. So see how was the end of the Mufsidûn (mischief-makers, corrupters)."

"And the king said: "Bring him to me." But when the messenger came to him, [Yusuf] said: "Return to your lord and ask him, 'What happened to the women who cut their hands? Surely, my Lord (Allah) is Well-Aware of their plot.

And Joseph placed his father and his brethren, and gave them a possession in the land of Egypt, in the best of the land, in the land of Rameses, as Pharaoh had commanded.— Genesis 47:11

The legacy of Joseph

Scholars and believers reveal Joseph is one of the most revered men in Islamic history. Having come through an especially noble line of patriarchs - Abraham, Isaac and Jacob - Joseph too was awarded the gift of prophecy like his forefathers. As Kisai, one of the foremost writers on the lives of the Qurʾānic prophets, states, this was also evident in the fact that Joseph was given a staff of light with five branches. On the first branch was written, ‘Abraham, friend of God’ on the second, ‘Isaac, sacrifice of God’; on the third, ‘Ishmael, pure of God’; on the four, ‘Jacob, Israelite of God’; and on the fifth, “Joseph, Righteous of God." [55]

The Quranic narrative about Joseph is perhaps one of the Book's most detailed accounts of the life and deeds of a prophet. Joseph, as a figure, is symbolic of the virtue of beauty - his life being a thing of beauty in itself. Most importantly, though, Joseph is admired as a great preacher of the Islamic faith, who had an extremely strong commitment to God and one who tried to get people to follow the path of righteousness. The Qur'an recounts Joseph's declaration of faith:

And I follow the ways of my fathers,- Ibrahim, Ishaak, and Ya'qub; and never could we attribute any partners whatever to Allah: that (comes) of the grace of Allah to us and to mankind: yet most men are not grateful.— Qur'an, sura 12 (Yusuf) ayah 38[56]

Joseph is also described as having the three characteristics of the ideal statesman: pastoral ability (developed while Joseph was young and in charge of his fathers flocks); house hold management (from his time in Potiphar’s house) and self-control (as we see on numerous occasions not just with Potiphar’s wife). “He was pious and God fearing, full of temperance, ready to forgive, and displayed goodness to all people.”[57]

Burial

It is hard to find sources that consistently agree on the actual dates of Joseph’s life. Scholars tend to see the story as a way for the descendants of Abraham to find their way to Egypt. Joseph is the reason the Israelites move to Egypt, which then allows for the story of Moses and the Exodus from Egypt to take place.

Historically, Muslims also associated Joseph's Tomb with that of the biblical figure. In recent years however, they claim that an Islamic cleric, Sheikh Yussuf (Joseph) Dawiqat, was buried there two centuries ago.[58] According to Islamic tradition, the biblical Joseph is buried in Hebron, next to the Cave of the Patriarchs where a medieval structure known as Yussuf-Kalah, the "Castle of Joseph", is located.[59]

Commentaries

Yūsuf is largely absent from the Hadīth. Discussions, interpretations and retellings of Sūrat Yūsuf may be found in the Tafsīr literature, the universal histories of al-Ṭabarī, Ibn Kat̲h̲īr, along with others, and in the poetry and pietistic literatures of many religions in addition to Judaism and Christianity.[60]

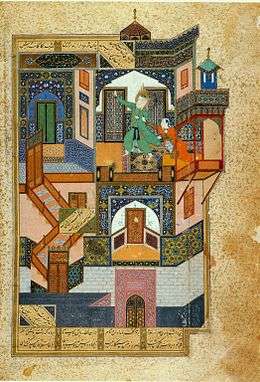

Yūsuf serves as a model of virtue and wisdom in pietistic literature. He is extolled in Ṣūfī manuals such as that of Abū Naṣr al-Sarrād̲j̲’s K. al-Lumaʿ as a paragon of forgiveness. “He also epitomizes the chastity that is based on complete trust in God, for it was his absolute piety that prompted God to personally intervene to prevent him from the transgression of succumbing to sexual temptation." [61] He is an archetype of wisdom and faith, although arguably still human (as is shown in his interactions with his brothers when in Egypt). As has been noted, commentary never fails to mention Yūsuf’s beauty—a strong theme in post-Ḳurʾānic literature. Firestone notes, “His beauty was so exceptional that the behavior of the wife of al-ʿAzīz is forgiven, or at least mitigated, because of the unavoidably uncontrollable love and passion that his countenance would rouse in her. Such portrayals are found in many genres of Islamic literatures, but are most famous in Nūr al-Dīn ʿAbd al-Raḥmān Dijāmī’s [q.v.] Yūsuf wa Zulayk̲h̲ā, which incorporates many of the motifs and attributes associated with his beauty in earlier works.”[61] Certainly by the 7th/13th century, and up to the 10th/16th in Persian areas at the very least, Yūsuf was incorporated into the world of art—and was thus considered a patron. In addition to poetry and other writing, paintings and other forms of art were composed to not only exemplify his physical beauty but his magnificent character as well.[61]

Below are a few notes about some, but not all, important influential commentaries—namely Arabic, Persian and Sufi from the mediaeval period. See references to get more information on each one.

Exoteric Commentaries in Arabic

"The Story of Joseph" is a running narrative, but the exoteric commentaries fill in gaps in the story, make connections and identifying characters. Adding detail to the novella is not uncommon, and most complement information already known from the holy texts. According to the Encyclopedia of Iranic, much of this comes from the Esra’Illiyat, that is, traditions drawn from the body of knowledge about Biblical events and people shared by Christians, Jews, and early Muslims. A fairly consistent source for this tradition goes back to the authority of Ibn Abbas (d. ca. 687) or Esma il b. Abd-al-Rahman Soddi (d. 745).[62]

Among the commentaries, Ṭabari includes the greatest number of traditions supplying information not found in the Qurʾānic story. Tabari’s commentary on Joseph presents numerous sources representing different traditions.[63] “All the Arabic commentaries on Surat Yusuf include explanations and discussions of lexicography and grammar to clarify the literal meaning of the Qurʾānic story of Joseph. They focus on smaller details, not big-picture meaning.[64]

Additional themes presented here have to do with the character of God, including that of God Ghalib. Mustansir Mir shows Joseph’s story as a vindication of God’s dominion and the continual fulfillment of his will. According to MW, this sura is the only one to point to the word "ghalib" as a divine attribute. The sura also highlights the way dominion is actually established in that God is subtle in accomplishing his will (God as Latif). God is also seen as "Alim" and "Hakm," all knowing and all wise.[65] This does not disregard the theme of balance between divine decree and human freedom.

Persian commentaries

Persian tafsirs vary considerably in the extent to which they included exegetical discussions of the technical nature and Arabic questions. Thus, some Persian commentaries on Surat Yusuf resemble their Arabic counterparts. Other commentaries consist mainly of a translation of the versus and storytelling, which is unlike Tabari’s style. Mystical readings of Joseph, from the 6th/12th century tafsir of Maybundi are an example of this influence.[66]

Storytelling becomes more prominent in Persian tafsirs. They are known especially for their colorful and dramatic depiction of scenes in the narratives. It is often described as “lively,” which can be seen in Joseph’s interactions with his brothers. Another example of Persian expansion of the language is when the brother’s realize that Joseph is going to keep Benjamin in Egypt. One of the brothers, often Rueben, is said to have threatened Joseph that he would yell so loudly that every pregnant woman would immediately deliver her child.[67]

Judaeo-Persian literature had strong influences on medieval Islamic writings as well. Scholars note that “genuine” Judaeo-Persian literature seemed to have been developed during the Īl-K̲h̲ān dynasty over Persia, from the end of the 7th/13th century on.[68]

Sufi commentaries

The Sufi tradition tends to focus its attention on the lessons and deeper meanings, “that may be elicited from the Qur’anic verses and the story of Joseph provides them with ample scope to draw lessons of mystical, ethical and theological and metaphysical significance."[67] All the commentaries of this tradition spend time on the themes of preordination and God’s omnipotence. Two teachings stand out here: “the first is that God is the controller and provider of all things and that human beings should have complete trust in Him and the second is the prevailing of the divine decree over human contrivance and design."[67] The love story itself is also a central theme in Sufi discussions.

The theme of love seeps into more than just the story of Joseph and Zolayka. Jacob becomes a prototype of the mystic lover of God and Zolayḵā goes from temptress to a lover moving from human to divine love.[69] There were two kinds of love present in the story—the passion of a lover as well as the devotion of a father to his lost son. Joseph also represents the eternal beauty as it is manifested in the created world.[66]

“The Persian versions include full narratives, but also episodic anecdotes and incidental references which occur in prose works, didactic and lyrical poetry and even in drama. The motif was suited to be used by Sufi writers and poets as one of the most important models of the relationship between the manifestation of Divine beauty in the world and the loving soul of the mystic."[66]

Joseph’s story can be seen as a parable of God’s way, a way which the mystic should focus his journey—following the way of love.

There was also a Jewish presence. “Persian Jews, far from living in a cultural vacuum in isolation, took also a keen interest in the literary and poetical works of their Muslim neighbors and shared with them the admiration for the classical Persian poetry." [70] Thus similar styles in meter and form translated easily between the two. The poet D̲j̲āmī is known for his reflection on stories such as Yūsuf and Zulayk̲h̲ā (d. 1414). Which was made accessible in Hebrew transliteration and are preserved in various libraries in Europe, America and in Jerusalem.[71]

Gender and Sexuality

The story can give us insight into Qurʾānic models of sexuality and gender and an understanding of hegemonic masculinity. In sura twelve, we encounter a prophet who is very different from other prophets in the Qurʾān but the tradition shows that prophets are chosen in the Qurʾānic world to guide other human beings to God.[72] He is similar to other prophets in that his story conveys God’s message but also is demonstrated in a biography that “begins and ends with God. For this reason all prophets are equal: their soul purpose is to highlight God’s divinity but not their own significance over against other prophets.”[73]

Even though Joseph was noble and loyal to God he did not resist Zolayḵā at first. Ibn Kathir uses Joseph’s resistance to Zolayḵā as a basis for the prophetic statement about men who are saved by God because they fear God. However, other scholars, especially women scholars such as Barbara Freyer Stowasser, think this interpretation is demeaning of women—perhaps believing that this seeks to show that women do not have the same connection. Stowasser writes: ‘Both appear in the Hadith as symbolized in the concept of fitna (social anarchy, social chaos, temptation) which indicates that to be a female is to be sexually aggressive and, hence, dangerous to social stability. The Qurʾān, however, reminds human beings to remain focused on submission to God." [74]

It is evident from the Islamic traditions that God is not chastising the mutual attraction and love between them but that he points to the associated factors that made their love affair impossible.[75] This is demonstrated later, by some accounts, when they are married.

See also

- Prophet Joseph (TV series)

- Biblical narratives and the Qur'an

- Legends and the Qur'an

- Jacob in Islam

- Muhammad in Islam

- Prophets of Islam

- Stories of The Prophets

- Yusuf

References

- ↑ Coogan, Michael (2009). The Old Testament: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press. pp. 70–72.

- ↑ Keeler, Annabel (15 June 2009). "Joseph ii. In Qur'anic Exegesis". Encyclopedia Iranica. XV: 34.

- ↑ Keeler, Annabel (15 June 2009). "Joseph ii. In Qurʾānic Exegesis". XV: 35.

- ↑ Wheeler, Brannon (2002). Prophets in the Qur'an. Continuum. p. 127.

- ↑ Wheeler, Brannon (2002). Prophets in the Qur'an. Continuum. p. 128.

- ↑ Bruijn (2013). "Yūsuf and Zulayk̲h̲ā". Encyclopedia of Islam; Second Edition: 1.

- ↑ Mir, Mustansir (June 1986). "The Qur'anic Story of Joseph". The Muslim World. LXXVI (1): 1. doi:10.1111/j.1478-1913.1986.tb02766.x.

- ↑ Keller, Annabel (15 June 2009). "Joseph ii. In Qurʾānic Exegesis". Encyclopedia Iranica. XV: 1.

- ↑ Quran 12:21

- ↑ al-Tabari, Muhammad ibn Jarir (Translated by William Brinner) (1987). The History of al-Tabari Vol. 2: Prophets and Patriarchs. SUNY. p. 148.

- ↑ al-Tabari, Muhammad ibn Jarir (Translated by William Brinner) (1987). The History of al-Tabari Vol. 2: Prophets and Patriarchs. SUNY. pp. 148–149.

- ↑ Quran 12:4

- 1 2 Wheeler, Brannon (2002). Prophets in the Quran: An Introduction to the Quran and Muslim Exegesis. Continuum. p. 128.

- ↑ Quran 12:5–6

- ↑ al-Tabari, Muhammad ibn Jarir (Translated by William Brinner) (1987). The History of al-Tabari Vol. 2: Prophets and Patriarchs. SUNY. p. 149.

- ↑ Khalil or Halil (Arabic: خليل ) means "friend".

- ↑ Sahih al-Bukhari, 4:55:593

- ↑ Quran 12:8–9

- ↑ Wheeler, Brannon (2002). Prophets in the Quran: An Introduction to the Quran and Muslim Exegesis. Continuum. pp. 130–131.

- ↑ Quran 12:10

- ↑ Wheeler, Brannon (2002). Prophets in the Quran: An Introduction to the Quran and Muslim Exegesis. Continuum. p. 127.

- 1 2 3 al-Tabari, Muhammad ibn Jarir (Translated by William Brinner) (1987). The History of al-Tabari Vol. 2: Prophets and Patriarchs. SUNY. p. 150.

- ↑ Quran 12:11–18

- ↑ Wheeler, Brannon (2002). Prophets in the Quran: An Introduction to the Quran and Muslim Exegesis. Continuum. pp. 150–151.

- ↑ Wheeler, Brannon (2002). Prophets in the Quran: An Introduction to the Quran and Muslim Exegesis. Continuum. p. 131.

- ↑ Wheeler, Brannon (2002). Prophets in the Quran: An Introduction to the Quran and Muslim Exegesis. Continuum. p. 130.

- ↑ Wheeler, Brannon (2002). Prophets in the Quran: An Introduction to the Quran and Muslim Exegesis. Continuum. p. 132.

- ↑ Quran 12:30

- ↑ Genesis, 39:1

- ↑ al-Tabari, Muhammad ibn Jarir (Translated by William Brinner) (1987). The History of al-Tabari Vol. 2: Prophets and Patriarchs. SUNY. p. 153.

- ↑ Quran 12:19–22

- 1 2 Tottoli, Roberto (2013). "Aziz Misr". Encyclopaedia of Islam, Three: 1.

- ↑ al-Tabari, Muhammad ibn Jarir (Translated by William Brinner) (1987). The History of al-Tabari Vol. 2: Prophets and Patriarchs. SUNY. p. 156.

- ↑ Quran 12:23–24

- ↑ Wheeler, Brannon (2002). Prophets in the Quran: An Introduction to the Quran and Muslim Exegesis. Continuum. pp. 133–134.

- 1 2 al-Tabari, Muhammad ibn Jarir (Translated by William Brinner) (1987). The History of al-Tabari Vol. 2: Prophets and Patriarchs. SUNY. pp. 157–158.

- ↑ al-Tabari, Muhammad ibn Jarir (Translated by William Brinner) (1987). The History of al-Tabari Vol. 2: Prophets and Patriarchs. SUNY. p. 160.

- ↑ Genesis, 39:1-23

- ↑ al-Tabari, Muhammad ibn Jarir (Translated by William Brinner) (1987). The History of al-Tabari Vol. 2: Prophets and Patriarchs. SUNY. pp. 161–163.

- 1 2 al-Tabari, Muhammad ibn Jarir (Translated by William Brinner) (1987). The History of al-Tabari Vol. 2: Prophets and Patriarchs. SUNY. p. 163.

- 1 2 Wheeler, Brannon (2002). Prophets in the Quran: An Introduction to the Quran and Muslim Exegesis. Continuum. p. 137.

- ↑ The History of al-Tabari, Volume III: Prophets and Patriarchs. State University of New York Press. 1987. p. 168.

- 1 2 Wheeler, Brannon (2002). Prophets in the Quran: An Introduction to the Quran and Muslim Exegesis. Continuum. pp. 137–138.

- ↑ al-Tabari, Muhammad ibn Jarir (Translated by William Brinner) (1987). The History of al-Tabari Vol. 2: Prophets and Patriarchs. SUNY. p. 167.

- ↑ al-Tabari, Muhammad ibn Jarir (Translated by William Brinner) (1987). The History of al-Tabari Vol. 2: Prophets and Patriarchs. SUNY. pp. 168–169.

- ↑ Wheeler, Brannon (2002). Prophets in the Quran: An Introduction to the Quran and Muslim Exegesis. Continuum. p. 139.

- ↑ al-Tabari, Muhammad ibn Jarir (Translated by William Brinner) (1987). The History of al-Tabari Vol. 2: Prophets and Patriarchs. SUNY. p. 169.

- ↑ al-Tabari, Muhammad ibn Jarir (Translated by William Brinner) (1987). The History of al-Tabari Vol. 2: Prophets and Patriarchs. SUNY. pp. 175–180.

- ↑ al-Tabari, Muhammad ibn Jarir (Translated by William Brinner) (1987). The History of al-Tabari Vol. 2: Prophets and Patriarchs. SUNY. p. 181.

- 1 2 Wheeler, Brannon (2002). Prophets in the Quran: An Introduction to the Quran and Muslim Exegesis. Continuum. p. 143.

- ↑ Redmount, Carol A. (1998). "Bitter Lives: Israel in and out of Egypt". The Oxford History of the Biblical World: 89–90.

- ↑ Quran 12:43

- ↑ Quran 7:103

- ↑ Quran 12:51

- ↑ De Sondy, Amanullah (4 December 2011). "Prophecy and masculinities: the case of the Qurʼanic Joseph". Cross Currents: 532.

- ↑ Quran 12:38

- ↑ Stone, Michael (1998). Biblical Figures Outside the Bible. Trinity Press International. p. 246.

- ↑ Israeli army returns to Arafat compound, BBC, October 1, 2002.

- ↑ "Patriarchal Burial Site Explored for First Time in 700 Years". Biblical Archaeology Review (May/June 1985).

- ↑ Firestone (2013). "Yusuf". Encyclopedia of Islam: 2.

- 1 2 3 Firestone (2013). "Yusuf". Encyclopedia of Islam: 3.

- ↑ Keeler, Annabel (15 December 2009). "Joseph ii. In Qur'anic Exegesis". Encyclopedia Iranica: 2.

- ↑ Keeler, Annebel (15 June 2009). "Joseph ii. In Qurʾānic Exegesis". Encyclopedia Iranica: 2.

- ↑ Keeler, Annebel (15 June 2009). "Joseph ii. In Qurʾānic Exegesis". Encyclopedia Iranica: 3.

- ↑ Mir, Mustansir (January 1986). "The Qur'anic Story of Joseph". The Muslim World. LXXVI: 5.

- 1 2 3 Flemming, Barbara (2013). "Yusf and Zulaykha". Encyclopedia of Islam, Second Edition: 1.

- 1 2 3 Keeler, Annebel (15 June 2009). "Joseph ii. In Qurʾānic Exegesis". Encyclopedia Iranica: 5.

- ↑ Fischel, W.J. (2013). "Judaeo-Persian". Encyclopedia of Islam, Second Edition: 1.

- ↑ Keeler, Annebel (15 June 2009). "Joseph ii. In Qurʾānic Exegesis". Encyclopedia Iranica: 4.

- ↑ Fischer, W.J. (2013). "Judaeo-Persian". Encyclopedia of Islam, Second Edition: 3.

- ↑ Fischer, W.J. (2013). "Judaeo-Persian". Encyclopedia of Islam, Second Edition: 2.

- ↑ De Sondy, Amanullah (December 2011). "Prophesy and Masculinities: The Case of the Qur'anic Joseph". Cross Currents: 531.

- ↑ De Sondy, Amanullah (December 2011). "Prophesy and Masculinities: The Case of the Qur'anic Joseph". Cross Currents: 533.

- ↑ De Sondy, Amanullah (December 2011). "Prophesy and Masculinities: The Case of the Qur'anic Joseph". Cross Currents: 535.

- ↑ De Sondy, Amanullah (December 2011). "Prophesy and Masculinities: The Case of the Qur'anic Joseph". Cross Currents: 537.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Yusuf. |

- Prophet Joseph (Yusuf)

- The meaning of Joseph's story in the Qur'an from the standpoint of his dream

- The Story of Yusuf.