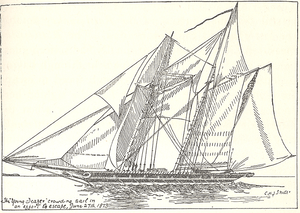

Young Teazer

Young Teazer | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name: | Young Teazer |

| Owner: | Samuel Adams |

| Launched: | 1813 |

| Homeport: | New York City |

| Fate: | Destroyed in explosion 27 June 1813 after trapped by HMS Hogue and HMS Orpheus |

| General characteristics | |

| Type: | Privateer |

| Tonnage: | 124 |

| Length: | 60 ft (18 m) (overall) |

| Sail plan: | Schooner |

| Complement: | 73 |

| Armament: | 5 guns plus 3 wooden dummy guns |

| Notes: | Source for info box dimensions[1] |

Young Teazer was a United States privateer schooner that a member of her crew blew up at Mahone Bay, Nova Scotia during the War of 1812 after a series of British warships chased her and after HMS Hogue trapped her.[2] The schooner became famous for the deadly explosion that killed most of her crew and for the folklore about the ghostly "Teazer Light."

Historical context

Many American privateers attacked British shipping off the coast of Nova Scotia during the War of 1812. This forced the British to deploy warships to patrol North American waters to forestall attacks and capture the American raiders.

The British naval strategy was twofold. First, the Royal Navy tried to protect British merchant shipping to and from Halifax, Canada and the West Indies. Second, the navy enforced a blockade of major American ports aimed at restricting American trade.

Both sides used privateers in the War of 1812 but the United States made greater use of them due to numerical inferiority of the United States Navy and the larger scale of British merchant trade relative to the United States's merchant trade. The Americans aimed to cause disruption through hit-and-run tactics, such as the capture of prizes and engaging Royal Navy vessels only under favorable circumstances. The American privateers were successful for the first part of the war.

Young Teazer's predecessor was the American privateer schooner Teazer, one of the first to put to sea when the United States declared war. HMS San Domingo captured Teazer in December 1812. Teazer was burnt at sea, but her crew, including her captain Frederick Johnson were released on parole, promising not to serve against the British until they had been exchanged for British prisoners of war. Teazer's owner Samuel Adams of New York, had the schooner Young Teazer built as a replacement.[3]

Engagement

After an initial successful cruise, Young Teazer left Portland, Maine on 3 June 1813 with 73 men[4] on her second and final cruise was under the command of William D. Dobson with Frederick Johnson serving as Lieutenant. On 1 June 1813, Shannon captured USS Chesapeake outside Boston Harbour. The British then towed Chesapeake to Halifax, Nova Scotia. While this was occurring, the crew of Young Teazer boarded a vessel off La Have, but allowed her and her crew to proceed as she was in ballast, and hardly worth taking. When the vessel reached Halifax she reported the privateer's presence and description.[5]

Shortly thereafter, Young Teazer captured two vessels off Sambro Island Light, at the entrance to Halifax Harbour. She then escaped possible capture by running into the harbor and raising British colors. The British discovered the ruse, but only after Young Teazer had left. Still, a number of British warships sailed in search of her.

While Young Teazer was attempting to capture ships near Halifax, the largest Nova Scotian privateer, the brig Sir John Sherbrooke, came upon her and the privateer narrowly escaped from Halifax harbour.

On 13 June 1813, the 74-gun third rate Hogue, commanded by Thomas Bladen Capel (who fought alongside Nelson in the Battle of Trafalgar), encountered Young Teaser and forced her into Halifax Harbour, but Dobson and Young Teazer escaped the harbour again. On 17 June 1813, HMS Wasp, which together with Rover had recaptured the brig Christiana, a prize that the privateer Young Teazer had taken, sailed in search of the privateer.[6] On 17 June 1813, Valiant was in company with Acasta when they came upon HMS Wasp in pursuit of an American armed merchant brig Porcupine off Cape Sable.[6] The three British ships continued the chase for another 100 miles (160 km) before they finally were able to capture the brig. However, Young Teazer briefly escaped into fog before Manly and Castor spotted her and commenced their chase. They too lost her.

A few days later, the frigate HMS Orpheus chased Young Teazer into Lunenburg Harbour. However, Orpheus lost her near Mahone Bay due to light winds. On 27 June, Hogue picked up the chase for 18 hours until she trapped Young Teazer in Mahone Bay between Mason Island and Rafuse Island.[7] Hogue was firing "viciously" and Orpheus soon joined as well. In the evening, Hogue prepared to send a boarding party in five of her boats.[7] Aboard Teazer, Capt. Dobson discussed plans to defend the privateer with his crew, reduced to 38 men by prize crews sent off in captured vessels. Lt. Johnson, known for his erratic behaviour on previous cruises, argued with Dobson and disappeared below. The schooner exploded a few minutes later.[8] Other accounts say Johnson, who feared hanging for breaking his parole, was seen rushing to the powder magazine.[7][9] The attacking British boats were three miles from Teazer. They returned to HMS Hogue after the explosion destroyed the schooner. Local residents rescued survivors, several of them badly burned, clinging to spars and the bow of the shattered hull of the schooner. Thirty of her crew died. The militia secured the survivors including the captain and took charge of the wreckage.[10] After being treated for their wounds, the captured privateersmen were sent to the Melville Island prisoner of war camp in Halifax.[7][Note 1] Most were soon returned to the United States as part of the regular exchange of prisoners of war.[12]

Legacy

The hull of Young Teazer, gutted but still partially afloat, was surrounded by floating bodies and wreckage, including her alligator figurehead and several Quaker guns – fake wooden cannons.[13] Much of the wreckage was salvaged, including some timbers that were used for building construction in Mahone Bay such as the present day Rope Loft in Chester. One of the lanterns is in possession of a citizen of Blandford, Nova Scotia, while a piece of the keel was used to build the wooden cross inside of St. Stephen's Anglican Church at Chester. A scorched fragment of the keel and a cane made from Teazer fragments is displayed at the Maritime Museum of the Atlantic in Halifax.

The name of the schooner was briefly revived in July 1813 when the Nova Scotian privateer schooner Liverpool Packet was captured and converted to an American privateer named Young Teazer's Ghost. However Young Teazer's Ghost failed to capture any ships and was soon recaptured by the British. Her name of Liverpool Packet was restored and she returned to capturing American ships until the war's end.

The story of Young Teazer inspired one of the best known ghost ships in Atlantic Canada, the so-called "Teazer Light". The folklore states a fiery glow or a flaming ship regularly appears on Mahone Bay near the site of the explosion, often near the 27 June anniversary. Accounts were first recorded in the late 19th century.[14] Folklorist Helen Creighton documented numerous versions of the story in her classic folklore book Bluenose Ghosts, although she noted that many sightings may be optical illusions during full moons.[15] The gruesome end of the schooner and the many ghost stories have made Young Teazer into a well known mythical figure in Nova Scotia.[16]

See also

Notes, citations, and references

Notes

Citations

- ↑ "Young Teazer-1813" On the Rocks, Nova Scotia Museum Marine Heritage Database

- ↑ Naval Chronicle, vol. 30, p. 438

- ↑ MacMechan (1947), pp. 181-194

- ↑ Halifax Chronicle, June 18, 1813

- ↑ Weekly Chronicle, 11 June 1813.

- 1 2 The London Gazette: no. 16770. p. 1746. 4 September 1813.

- 1 2 3 4 The London Gazette: no. 16787. p. 2031. 12 October 1813.

- ↑ Eyewitness account of Young Teazer survivor John Quincy related in "Blowing up the Young Teazer", The War, New York, July 20, 1813.

- ↑ Maclay (1899), p. 147.

- ↑ DesBrisay (1895), p. 520.

- ↑ The London Gazette: no. 17038. p. 1395. 11 July 1815.

- ↑ "Blowing up the Young Teazer", The War, New York, July 20, 1813

- ↑ C.H.J. Snider, Under the Red Jack, page 127

- ↑ DesBrisay (1895) p. 521

- ↑ Creighton, Helen, Bluenose Ghosts Toronto: Ryerson Press (1857) p.118-120

- ↑ Tanner (1976).

References

- Collins, Gilbert. "Blowing up of the Teazer - Mahone Bay, Nova Scotia". In Guidebook to the historic sites of the War of 1812.Guidebook to the Historic Sites of the War of 1812 by Gilbert Collins.

- DesBrisay, M.B. (1895) History of The County of Lunenburg. (Toronto:William Briggs).

- Maclay, Edgar Stanton (1899) A history of American privateers. (New York: D. Appleton and company). pp. 446–448 Book On Line

- Tanner, Dwight (1976) "Young Teazer, the Making of a Myth", Nova Scotia Historical Quarterly, vol. 6, .

- MacMechan, Archibald (1921) "The 'Teazer' Light". In Sagas of the Sea. (In the Table of Contents, MacMechan indicates his primary sources are Desbrisay as well as the Logs for HMS Hogue and HMS Orpheus)

- MacMechan, Archibald. The 'Teazer' Light. In Tales of the Sea. (McClelland & Stewart).