Wooden reed care

Due to their natural composition, cane musical reeds may hold bacteria or mold, which can affect one's health and the quality of sound produced. Some of the basic instruments that use reeds include the clarinet, saxophone, oboe and bassoon. Proper care of reeds will extend their longevity and control bacterial growth.

Reed care

Reed preparation

Wooden reeds must be moistened prior to playing. Many musicians place the reed in their mouths to moisten them with saliva. In preparing the reed for playing, water is less corrosive than saliva. Soaking a reed in water for about five minutes is a good alternative to saliva. It also reduces the chance of food particles damaging the reed.[1] However, soaking reeds in already humid weather may cause them to become water-logged; extreme environments can damage reeds. They should not be kept too dry or too wet, or they will become warped.[2]

Dark spots on new reeds are not an indication that the reeds are poor, but if the dark spots have formed after several uses, it may be an indication of mold growth. Therefore, it is also suggested that one soak one's reed in hydrogen peroxide. Five minutes a day is sufficient to keep the reed clean from bacteria and mold. It should also destroy any salivary enzymes that may have collected on the reed while playing. If hydrogen peroxide is not available, musicians need to be sure to rinse the reed in running water and then dry it before storing.

Reed storage

Reed storage affects the reed life and may help or hinder bacterial and mold growth. Putting a dirty reed in a reed case just allows mold and bacteria to grow in the case every time the reed is placed in it. Mold can also grow if reeds are kept in a tightly sealed container in humid environments. Every time the container is opened moisture is caught inside, allowing mold to grow.[2] Storage in a cool, dry environment, like a refrigerator, helps to slow microbial growth.[3] Light and ultraviolet radiation will not damage the reed structure unless exposure time is excessive or if radiation levels are high.[4] A cool cabinet with a desiccant, such as calcium sulfate, can also serve as a good storage area. Not only do cooler environments discourage bacterial growth, but there are almost no harmful effects on a normal reed.

Heat can have a damaging effect on the chemical authenticity of the reed. Soaking the reed in nearly boiling water is not recommended for cleaning. The hydrogen bonds begin to break down between 60 °C and 80 °C. At 100 °C much of the molecular structure is lost. Heating dry wood can also cause splitting.[4] When not being used, reeds should be kept covered. There are many products available specifically for reed storage.

Personal hygiene and reed care

Reed longevity is affected by the musician's personal hygiene habits. As many band directors encourage, eating prior to playing is not good for one's instrument or for one's own health. Old food is a gold mine for bacterial growth, especially microbial flora. Appropriately, one might brush their teeth, floss, and use mouthwash, before and after playing to lower risks of illness.[3] Using a reed while sick with a cold increases mucous discharge from the throat and lungs onto the reed. This will more quickly strip hemicellulose from the reed. Hemicellulose maintains the reed's ability to hold water.[4] Using a reed while sick quickly decreases the reed's ability to absorb water; this is irreversible damage. Also, using a reed while sick increases the chance for reinfection. It is common that musicians just use old spent reeds while ill to keep from damaging good reeds.

The effect of saliva on reeds

pH Levels

Normally, saliva is slightly acidic and has a pH less than 7, but it can vary between 6 and 8. The pH inside the mouth depends on the salival flow rate because the higher the flow rate of saliva the more salival bicarbonates are present. Bicarbonates in the saliva raise the pH inside the mouth. When there is no or low saliva flow, also known as xerostomia, the pH inside the mouth is around 6. When salival flow rate is high the pH is about 8. During a concert, if a musician is suffering from xerostomia, also known as dry mouth, the saliva pH is expected to be acidic.[4]

Nervousness in concert situations can also lead to xerostomia, but more importantly nervousness can cause rapid breathing. This increases carbon dioxide (CO2 ) flow out of the body and causes respiratory alkalosis. The decrease in CO2 affects the amount of bicarbonates available. Salivary bicarbonates are synthesized from CO2. The less CO2 available, the fewer bicarbonates can be synthesized; therefore, the pH drops.[4] Under this condition it is wise to use salival flow stimulants. Continually changing the pH environment the reed encounters damages the reed. If the pH level inside the mouth can be kept at rehearsal level, the life of the reed will increase.

Consequently, the environment for regular rehearsal differs. The musician may not be as nervous, and they might be holding their breath more to play. Holding one's breath increases CO2, also known as respiratory acidosis. Therefore, saliva is expected to be more alkaline. In a reeds life, it is more likely to face alkaline environments because rehearsals occur more often than concerts. The alkaline environment increases the amount of hemicellulose stripped from the reed matrix.[4] Although hemicellulose is depleted, it is better for the reed to remain in an overall consistent environment.

Contaminants in saliva

Even though salival pH decreases the hemicelluloses coating on reeds, it has little effect on the reed matrix compared to the contaminants found in saliva. Amines and glycoproteins have been found in the reed matrix: salivary mucosins, Proline-rich Glycoproteins, alpha-amylases, peroxidase, Carbonic Anhydrase, Fucose-rich glycoproteins, Immunoglobulin, Kallikrein, Lactoferrin, and Fibronectrin.[4]

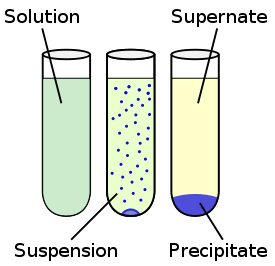

Oral bacterium already in one's mouth removes the sugar containing components from glycoproteins in saliva. This removal of sugar forms a precipitate or a non-soluble by-product. The protein precipitate formed in saliva is normally rich in calcium and low in solubility. Also, alpha-amylase contains a significant level of sialic acid. When alpha-amylase combines with saliva, the enzymes hydrolyze and release the sialic acid, forming another water-insoluble precipitate.[4] These two precipitates combine to form an impenetrable layer on the reed, which prevent the reed from fully hydrating. In time, the reed will become stiff and brittle.

Types of Bacteria found in reeds

Streptococcal bacteria have been found living inside the walls of water-conducting xylem cells in spent reeds. Streptococcal bacterium is a common bacterium that causes illness to the throat, including sore throat and strep throat.[5]

Also the common bacterium, Staphalcoccus Epidermitis, completely covers the reed. It is also found all over the mouth and hands on virtually everyone; therefore, it is innocuous. Staphalcoccus Epidermitis is known as one of the bacteria which remove the sugars from saliva, which causes the deposition of sialic acid. This type of bacteria becomes dormant in the absence of water.[4] Drying reeds before storing will help stop the growth of Staphalcoccus Epidermitis.

The effect of bacteria on reeds

Bacterium affects the playability of the reed in three ways. First, it adds mass to the reed tip. A bacterial coating actually dampens the vibrating reed, causing it to play at lower frequencies. Secondly, it reduces the reed's range of motion and bending. This will decrease the reeds ability to maintain sound. Lastly, it changes the overall shape of the reed, which directly affects the tone quality.[4]

The Effect of Reed Bacteria on the Body

The bacteria found covering reeds may cause respiratory infections such as colds, influenza, pneumonia, tuberculosis, herpes fibrilis (cold sores), and other rare diseases. However, contact is necessary for the transfer of microbial infection. The airborne organisms are known to be virtually harmless. Infection will not spread between musicians unless there is contact with the bacteria.[3]

Specifically, streptococci can cause varying levels of infections from mild to life-threatening. Starting in the 1980s, group A streptococci have increased in prevalence and have been the cause of rheumatic fever and other invasive infections.[5] The mucous membranes found in the nose and throat are primary sites for infection and transmission of group A streptococci.[5] The mucus membranes are in direct contact with the reed during playing; therefore, if infection does occur it is likely it will derive from the group A streptococci.

When group A streptococcal infects the throat, it is also known as streptococcal pharyngitis, or strep throat. Redness, trouble swallowing, swelling of regional lymph nodes, and localized pain are common complaints of streptococcal pharyngitis. Leukocytosis, an abnormally high white blood level, is a common reaction to the infection. Streptococcal pharyngitis is most prevalent during colder seasons. Many marching bands play on cold nights at football games. Exposing musicians to such weather and bacterium may increase the likelihood of infection.[6]

Notes

- ↑ Stambler, David. "Single Reed Reed Basics." 2005. Penn State University. http://www.capitolquartet.com/admin/pdf/Reedbasics.pdf.

- 1 2 Williams, Floyd. "Reeds: How to Care for Them and How to Improve Their Response." Australian Clarinet and Saxophone. June 2003: 11-12

- 1 2 3 Bryan, A. H. (1960). Band instruments harbor germs. Music Educators Journal, 46(5), 84-85.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Casadonte, Donald Jay (1995). The Clarinet Reed: AN Introduction to its Biology, Chemistry, and Physics (Ph.D. thesis). The Ohio State University. Bibcode:1995PhDT.......186C.

- 1 2 3 Horaud T., Bouvet A., Leclercq R., Montclos H. d. and Sicard M. Streptococci and The Host. New York: Plenum Press. 1997: 255, 537.

- ↑ Wannamaker, LW. "Differences between streptococcal infections of the throat and of the skin. Part I." New England Journal of Medicine. 282 (1970): 23-31.