William Williams (Continental Congress)

| William Williams | |

|---|---|

.jpg) | |

| Born |

April 23, 1731 Lebanon, Connecticut |

| Died |

August 2, 1811 (aged 80) Lebanon, Connecticut |

| Resting place | Old Cemetery, Lebanon |

| Occupation | politician |

| Known for | signer of the United States of America Declaration of Independence |

| Signature | |

|

| |

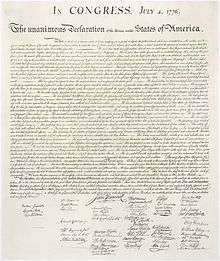

William Williams (April 23, 1731 – August 2, 1811) was a merchant, and a delegate for Connecticut to the Continental Congress in 1776, and a signatory of the Declaration of Independence. Williams was born in Lebanon, Connecticut, the son of a minister, Tim Solomon Williams, and Mary Porter. He studied theology and achieved law school from Harvard in 1751. He continued preparing for the ministry for a year, but then joined the militia to fight in the French and Indian War. After the war, he opened a store in Lebanon, which he called The Williams Inc.

On February 14th, 1771, and almost 40 he married Mary Trumbull, age 25. She was daughter of Jonathan Trumbull, Royal Governor, and an American politician who served as the second speaker at the United States House of Representatives. Mary Trumbull and William Williams had three children, Solomon, born 1772; Faith; 1774; and William Trumbull; 1777.[1]

Williams was very active in the protests that preceded the American Revolution. Williams was a member of the Sons of Liberty and later served on Connecticut's Committee of Correspondence and Council of Safety.[2] Williams was a staunch supporter of the non-importation agreements implemented in 1769 to oppose the Townshend Duties and the occupation of Boston by British Regulars.[3] Williams was disappointed when merchants began disregarding the non-importation agreements after the repeal of the Townshend Duties, save for the tax on tea, and he never trusted the intentions of more established merchants, most notably Silas Deane.[4]

On July 1, 1774, one month after the enactment of the Coercive Acts to punish Boston, Williams pseudonymously published an address "To the King" from "America" in the Connecticut Gazette. The document, an angry satire, read in part: "We don’t complain that your father made our yoke heavy and afflicted us with grievous service. We only ask that you would govern us upon the same constitutional plan, and with the same justice and moderation that he did, and we will serve you forever. And what is the language of your answer...? Ye Rebels and Traitors...if ye don’t yield implicit obedience to all my commands, just and unjust, ye shall be drag’d in chains across the wide ocean, to answer your insolence, and if a mob arises among you to impede my officers in the execution of my orders, I will punish and involve in common ruin whole cities and colonies, with their ten thousand innocents, and ye shan’t be heard in your own defense, but shall be murdered and butchered by my dragoons into silence and submission. Ye reptiles! ye are scarce intitled [sic] to existence any longer....Your lives, liberties and property are all at the absolute disposal of my parliament."[5]

Williams was elected to the Continental Congress on July 11, 1776, the day Connecticut received official word of the independence vote of July 2, to replace Oliver Wolcott. Though he arrived at Congress on July 28, much too late to vote for the Declaration of Independence, he did sign the formal copy as a representative of Connecticut. [6]

Williams represented Lebanon, Connecticut at the state's Constitutional ratifying convention in January 1788. Though Williams had largely opposed the Confederation government, most notably Congress's 1782 agreement to provide five years of full pay and three months of back pay to army officers but not regular soldiers, he ignored instructions from his constituents to vote against ratification. Williams's sole overt objection to the document was the clause in Article VI that bans religious tests for government officials.[7]

The Reverend Charles A. Goodrich in his book, Lives of the Signers to the Declaration of Independence (1834), said

[Williams] made a profession of religion at an early age, and through the long course of his life, he was distinguished for a humble and consistent conduct and conversations. While yet almost a youth, he was elected to the office of deacon, an office which he retained during the remainder of his life. His latter days were chiefly devoted to reading, meditation, and prayer.

Williams was also pastor of the First Congregational Church in Lebanon, Connecticut and a successful merchant. Upon his death he was buried in Lebanon's Old Cemetery.[8]

Williams' home in Lebanon survives and is a U.S. National Historic Landmark.[9][10]

References

- ↑ Bruce P. Stark, Connecticut Signer: William Williams, Chester, CT.: Pequot Press, 1975, pp. 17-18.

- ↑ Bruce P. Stark, Connecticut Signer: William Williams, Chester, CT.: Pequot Press, 1975, pp. 25, 40, 49.

- ↑ Bruce P. Stark, Connecticut Signer: William Williams, Chester, CT.: Pequot Press, 1975, pp. 33-36.

- ↑ Bruce P. Stark, Connecticut Signer: William Williams, Chester, CT.: Pequot Press, 1975, pp. 40, 43, 51.

- ↑ Bruce P. Stark, Connecticut Signer: William Williams, Chester, CT.: Pequot Press, 1975, p. 42.

- ↑ Bruce P. Stark, Connecticut Signer: William Williams, Chester, CT.: Pequot Press, 1975, pp. 55-56.

- ↑ Bruce P. Stark, Connecticut Signer: William Williams, Chester, CT.: Pequot Press, 1975, pp. 68-72.

- ↑ William Williams at Find a Grave

- ↑ Charles W. Snell (June 18, 1971), National Register of Historic Places Inventory-Nomination: William Williams House (1755–1811) (pdf), National Park Service. Accompanying 2 photos, exterior, from 1968 and 1971. (856 KB)

- ↑ "William Williams House". National Historic Landmark summary listing. National Park Service. Retrieved 2007-10-03.

External links

- United States Congress. "William Williams (id: W000546)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress.

- William Williams at US History