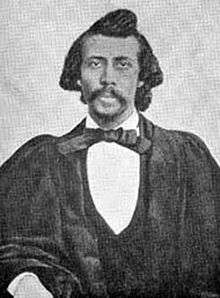

William H. Day

William Howard Day (October 16, 1825 – December 3, 1900) was a black abolitionist, editor, educator and minister

Early life

Day was born in October 16, 1825, in New York City His mother was Eliza, a founding member of the first AME Zion Church and an abolitionist. His father, John, was a sail maker, veteran of the War of 1812 and Algiers, in 1815. He died when his son was four. The Willistons of Northampton, Massachusetts raised him. They asked his mother to allow them to educate him.

Early work

In 1834, the young Day joined Henry Highland Garnet and David Ruggles to form the all-male Garrison Literary and Benevolent Association. Day attended Oberlin College and graduated in 1847. He dedicated his life to the rights of Blacks in the U.S. In 1848 he was in Cleveland where he became the secretary of the National Negro Convention.[1]

Day was editor of one of the first weekly African-American newspapers, the Aliened American.[2] Published in Cleveland, Ohio, Day used the newspaper to support the abolitionist cause, as in this excerpt from April 9, 1853: We speak for Humanity. If Humanity be a unit, wherever it is cloven down, wherever rights common to human beings are infringed, there we do sympathize.[3]

On November 25, 1852, Day married Lucy Stanton (abolitionist), a 1846 graduate of Oberlin College. In 1858 their only child was born, Florence Day. In 1858, Day abandoned his wife and child. Day and Lucy Stanton were legally divorced in 1872.[4] In 1873, Day married Georgia F. Bell.[5]

In 1858, Day was elected president of the National Board of Commissioners of the Colored People by the Black citizens of Canada and the United States. Day was also active in the cause of the civil rights of the northern black minority. In 1858, he and his wife Lucy challenged racial segregation in public transportation in Michigan. In the 1858 case Day v. Owen, the Republican-dominated Michigan Supreme Court ruled against him and upheld segregation.[1] Day left for a European lecture tour the same year and returned to the USA after the end of the American Civil War. He rose to be an lead the local school board.[6]

Death

Day died in Harrisburg on December 3, 1900, at the age of 75. William Howard Day Cemetery was established in nearby Steelton in the 1900s as a burial place for all people, including people of color who were denied burial at the nearby Baldwin Cemetery. It remains a popular burial site for local African American families.[7]

References

- 1 2 Volk, Kyle G. (2014). Moral Minorities and the Making of American Democracy. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. pp. 158–163, 213. ISBN 019937192X.

- ↑ Stirling, Dorothy (1973). Speak out in thunder tones. p. 374.

- ↑ Hutton, Frankie (1993). The Early Black Press in America, 1827 to 1860. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press. p. 36. ISBN 0313286965.

- ↑ "Encyclopedia of Cleveland History".

- ↑ Davis, Russell H. (1969). Memorable Negroes in Cleveland's Past. Cleveland, OH: Western Reserve Historical Society.

- ↑ William Howard Day, Spartacus, retrieved 24 July 2015

- ↑ "William H. Day, minister, abolitionist, and college founder". African American Registry. African American Registry. Retrieved 27 June 2014.

Further reading

- Volk, Kyle G. (2014). Moral Minorities and the Making of American Democracy. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. ISBN 019937192X.