James Blish

| James Blish | |

|---|---|

| Born |

May 23, 1921 East Orange, New Jersey, United States |

| Died |

July 30, 1975 (aged 54) Henley-on-Thames, England, United Kingdom |

| Pen name | William Atheling, Jr. |

| Occupation | Writer, critic |

| Period | 1940–1975 |

| Genre | Science fiction, fantasy |

|

| |

| Signature |

|

James Benjamin Blish (May 23, 1921 – July 30, 1975) was an American author of fantasy and science fiction. Blish also wrote literary criticism of science fiction using the pen-name William Atheling, Jr.

Early life

Blish was born at East Orange, New Jersey.[1]

Career

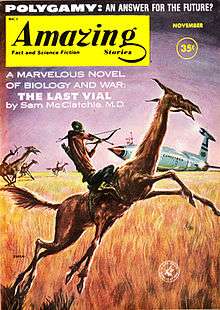

In the late 1930s to the early 1940s, Blish was a member of the Futurians.[2] He broke into science fiction print with two stories published by Frederik Pohl in Super Science Stories, "Emergency Refueling" in March and "Bequest of the Angel" in May 1940. ISFDB catalogs ten more stories published during 1941 and 1942, but only two in the next five years.[3]

Blish trained as a biologist at Rutgers and Columbia University, and spent 1942–1944 as a medical technician in the United States Army. After the war he became the science editor for the Pfizer pharmaceutical company. His writing career progressed until he gave up his job to become a professional writer.

He is credited with coining the term gas giant, in the story "Solar Plexus" as it appeared in the anthology Beyond Human Ken, edited by Judith Merril. (The story was originally published in 1941, but that version did not contain the term; Blish apparently added it in a rewrite done for the anthology, which was first published in 1952.)[4]

From 1962 to 1968, Blish worked for the Tobacco Institute.[5]

Between 1967 and his death from lung cancer in 1975, Blish wrote authorized short story collections based upon the 1960s TV series Star Trek. He wrote 11 volumes adapting episodes of the series. He died midway through writing Star Trek 12. His second wife, J. A. (Judith Ann) Lawrence, completed the book, and later completed the adaptations in the volume Mudd's Angels. In 1970 he wrote Spock Must Die!, the first original novel for adult readers based upon the series.

The archive of Blish's books and papers is deposited at the Bodleian Library in Oxford.[6] Blish is buried in Holywell Cemetery, Oxford.

Works

Cities in Flight

Perhaps Blish's most famous works were the "Okies" stories, known collectively as Cities in Flight, published in the science-fiction digest magazine Astounding Science Fiction. The framework for these was set in the first of four novels, They Shall Have Stars (first UK publication under the alternative title of Year 2018!), which introduces two essential features of the series. The first is the invention of the anti-aging drug ascomycin; Blish's employer Pfizer makes a thinly disguised appearance as Pfitzner in a section showing the screening of biological samples for interesting activity. (Pfizer also appears in disguise as one of the sponsors of the polar expedition in a subsequent book, Fallen Star). The second is the development of an antigravity device known as the "spindizzy". Since the device becomes more efficient when used to propel larger objects, entire cities leave an Earth in decline and rove the stars, looking for work among less-industrialized systems. The long life provided by ascomycin is necessary because the journeys between stars are time-consuming.

They Shall Have Stars is dystopian science fiction of a type common in the era of McCarthyism, and even includes a villain who is a cross between J. Edgar Hoover and Joseph McCarthy—and named MacHinery. The second, A Life For The Stars, is a coming of age story set amid flying cities. The third, Earthman, Come Home, is a series of loosely connected short stories detailing the adventures of a flying New York City; the title piece was selected as one of the best novellas prior to 1965 by the Science Fiction Writers of America and included in The Science Fiction Hall of Fame, Volume Two.

For his fourth and final installment, The Triumph of Time (UK title: A Clash of Cymbals), Blish set the end of his literature's universe in AD 4004.[7] (The chronology in early editions of They Shall Have Stars differed somewhat from the later reprints, indicating that Blish, or his editors, may not have planned this at the beginning of the series.) A film version of Cities in Flight was in pre-production by Spacefilms in 1979, but never materialized.[8]

The Haertel Scholium

This term describes the background of a number of Blish's science fiction short stories. Three distinct technologies, their invention, and consequences are outlined. There is some overlap between the Cities in Flight saga and that of The Seedling Stars, mainly through one piece of technology, the Dirac Radio. Another unifying concept is the first trans-luminal drive — The Haertel Overdrive.

Adolph (Dolph) Haertel developed the drive in order to reach Mars rapidly (Welcome to Mars!). Haertel Cosmology, the result of Haertel's science, in Blish's words, "swallowed Einstein the way Einstein swallowed Newton — that is to say, alive." Haertel goes on to develop the drive to allow the entry of men into interstellar space. The DFC-3, piloted by Garrard, reaches Alpha Centauri, where extraterrestrial first contact is made with the Clinesterton Beademung (Short Story: "Common Time"). The Drive at this stage is not well developed, and initially suffers from dramatic chrono-swings from almost complete time-freeze to the hyper-time of pseudo-death. Proposed Clarification: The traveler experiences thoughts and sensations "subjective time" at a rate which disagrees radically from that of ship and physiology. With refinement, the drive becomes a valid method of interstellar travel, though not without mishap and adventure as other forms of travel are tried, such as the near-useless (though fascinating and instructive for the quantum physicist) Arpe Drive ("Nor Iron Bars").

Refinement of the drive allows the exploration of the near-stars, as well as the Coal-Sack Nebula, wherein the beings known as Angels are first encountered by the hero Jack Loftus, Sylvia McCrary and Dr. Challenger, as well as a long lived and powerful civilization, the Hegemony of Malis (The Star Dwellers). Ultimately deduction, and a first hand experience of a planet deliberately maintained in a state of genocidal savagery ("A Dusk of Idols"), coupled with expert reasoning reveals that the Hegemony is malignant, and Humanity rebels. Mission to the Heart Stars reveals the true nature of the Hegemony, and with the help of a stowaway Angel, Hesperus, humanity is freed of its bondage, and made companions of the Angels.

The stories considered part of the Haertel Scholium include A Case of Conscience and the Pantropy series (see below). Both are anomalous in that they do not appear to have the Dirac Radio, though it is plausible to assume that A Case of Conscience takes place before the development of the Dirac.

A unifying force of galactic civilization is the Dirac Radio, developed by Dr. Thor Wald. This radio is able to permit faster-than-light radio transmission. It has an additional and unsettling ability — within every transmission, is the sum total of all transmissions from the device, throughout all of time and space. The Department of Intelligence, headed by Captain Robert Weinbaum, and aided by the beautiful video reporter Dana Lje, make this shattering discovery. Three hundred years later, the "Service" is the dominant government of the Galaxy, and Dirac is the center of their power, with a network built from Haertel Overdrive spacelanes. ("Beep", the inspiration for tachyons).

Four thousand years in the future, Human civilization has met its first full antagonist — the Green Exarchy. A system of many civilizations ruled by a non-human emperor, the Green Exarch, this represents a significant threat to High Earth. The Green Exarch has at his employ the extremely dangerous shapeshifting (protean) agents known as Vombis, who will appear human, but do not revert to their true shape when killed, giving them an air of great mystery and menace.

The Haertel Overdrive is now called the Imaginary Drive, and the Dirac is still in common use. High Earth remains the center of Human civilization. That civilization is remarkably advanced — for all practical intents, humans are now immortal. A memory cleanse known as Baptism permits those filled with ennui to begin lives anew, though there are side effects from subconscious recall. A quasi-religious group known as Sagittarians also play a part. The most important financial force in the empire of High Earth is the Traitor's Guild, who permit money to flow from system to system in reward of treachery to system governments, producing a Feudatory system between worlds, though not at the expense of internal stability. Traitors skillfully employ advanced biotechnology to further their aims, and are known to employ fungal cytotoxins, DNA reverse transcription mutation agents (to inject false memories and appearances in order to forestall recognition and testimony during interrogations), as well as technology to petrify dead bodies in order to make up wall fortifications in far offworld planets. The Traitors Guild may be found on all planets (A Traitor of Quality, Section in The Quincunx of Time with a lecture about the Traitor's Guild, and The Green Exarchy).

Five thousand years later still, Human civilization has gone through many Rebirths, or Renaissances. The chance infusion of a mentality from 1949 through a freak combination of the active mode of the Dirac within a Radio Telescope results in the formation, after many adventures and an ultimate resurgence of Man, the Quint, the Autarch of Rebirth V. A computer of this far future time uses the Dirac as both a means of communication and infinite memory storage (Midsummer Century). Its existence was foretold at the time of Capt. Weinbaum, though no-one could interpret its messages then (The Quincunx of Time, novella expansion of "Beep").

After Such Knowledge

Blish declared that another group of novels was a trilogy, each dealing with an aspect of the price of knowledge, and given the overall name of After Such Knowledge (the title taken from a T. S. Eliot quote). The first published, A Case of Conscience (a winner of the 1959 Hugo Award as well as 2004/1953 Retrospective Hugo Award for Best Novella),[9] showed a Jesuit priest confronted with an alien intelligent race, apparently unfallen, which he eventually concludes must be a Satanic fabrication. The second, Doctor Mirabilis, is a historical novel about the medieval proto-scientist Roger Bacon. The third, consisting of two very short novels, Black Easter and The Day After Judgment, was written using the assumption that the ritual magic for summoning demons as described in grimoires actually worked. In Black Easter, a powerful industrialist and arms merchant arranges to call up demons and set them free in the world for a night, resulting in nuclear war and the destruction of civilization; The Day After Judgment is devoted to exploring the military and theological consequences.

The Seedling Stars (Pantropy)

Blish's "Pantropy" tales were collected in the book The Seedling Stars. In these stories, humans are modified to live in various alien environments, this being easier and vastly cheaper than terraforming.

- Book One ("Seeding Program") is about the inception of Pantropy, when the Pantropy program appears to have deteriorated into hideous genetic experimenting and has been outlawed. It describes Sweeney, a modified ("adapted") human whose metabolism is based on liquid ammonia and sulfur bonds and whose bones are made from ice IV, who is inserted into a colony on Ganymede by the Terran Port Authority (a para-military organization) to capture a renegade scientist and end his plans to seed modified humans on distant worlds. However, the government really only tries to derail pantropy because it will cut their profits from terraforming attempts. Sweeney is surprised to find a well established, functioning community on Ganymede and eventually realizes that he was just used as an expendable agent and that he has been fed false hopes about the possibility of being changed into a normal human being who could live on earth. Having found a real home, he switches sides and with his help the Ganymede colony manages to launch their seed ships to secret destinations, beyond the reach of the corrupt government.

- Book Two ("The Thing in the Attic") depicts a very successful seeding project. It tells the story of a small group of intellectuals from a primitive culture of modified monkey-like humans living in the trees of their jungle world. Having openly voiced the opinion that the godly giants do not literally exist as put down in the book of laws, they are banished from the treetops for heresy. In their exile on the ground they have to adapt to vastly different circumstances, fight monsters resembling dinosaurs, and finally happen upon the godly giants — who turn out to be human scientists who have just arrived on the world to monitor the progress of the local adapted humans. The protagonists are told by the scientists that their whole race must eventually leave the treetops to conquer their world and that they have become pioneers of some sort for accomplishing survival.

- Book Three ("Surface Tension") gives another example of a culture of adapted humans: A pantropy starship crashes on an ocean world, Hydrot, which is on orbit around Tau Ceti. With no hope for rescue, the few survivors modify their own genetic material to seed microscopic aquatic "humans" into the lakes and puddles of the world and leave them a message engraved on equally scaled metal plates. The story then tells how over many seasons, the adapted human newcomers explore their aquatic environment, make alliances, invent tools, fight wars with hostile beings and finally gain dominance over the sentient beings of their world. They develop new technologies and manage to decipher some of the message on the metal plates. Finally they build a wooden "space ship" (which turns out to be two inches long) to overcome the surface tension and travel to "other worlds" — the next puddle — in search of their ancestry, as they have come to realize that they are not native to their world.

- Book Four ("Watershed") takes a look at the more distant future. A very long time after the beginning of the Pantropy program, a starship crewed by "standard" humans is en route to some unimportant backwater planet to deliver a pantropy team who are "adapted" humans resembling seals more than humans. Due to racial prejudices, tension mounts between the crew and the passengers on board. When the captain decides to restrict the passengers to their cabins to prevent the situation from escalating, the leader of the adapted humans informs him that the planet ahead is Earth, where the "normal" human form once developed. He challenges the "normal" humans to follow him onto the surface of their ancestral home planet and prove that they are superior to the "adapted" seal people who will now be seeded there — or admit that they were beaten on their own grounds. The story concludes as the captain and his lieutenant silently ponder the possibility that they, being "standard" humans, are just a minority, and an obsolete species.

"Watershed" makes reference to the planet, Lithia, which is the centerpiece of A Case of Conscience, and it must be assumed that the Pantropy stories take place in a slightly different Universe, given the respective fates of the planet within each Universe.

Other

Blish collaborated with Norman L. Knight on a series of stories set in a world with a population a thousand times that of today, and followed the efforts of those keeping the system running, collected in one volume as A Torrent of Faces. Included in this collection is Blish's Nebula-nominated novella "The Shipwrecked Hotel", a story about a semi-submerged hotel with approximately a million guests which experiences a massive computer failure (a result of escaped silverfish) and begins to sink. Running parallel to all the side-plots is the inevitable catastrophe of the mile-wide asteroid "Flavia" striking Canada.

The stories are also notable for including a form of pantropy that has been used to modify humans into a sea-dwelling form known as "Tritons".

Selected bibliography

Cities in Flight

- They Shall Have Stars (Faber 1956, Avon T-193 1957 published under the title Year 2018![10])

- A Life for the Stars (G. P. Putnam's Sons 1962, Avon H-107 1963)

- Earthman Come Home (G. P. Putnam's Sons 1955; Avon T-225 1956, originally published as four short stories)

- The Triumph of Time, (Avon T-279 1958; published in the UK as A Clash of Cymbals Faber 1959)

A one-volume collection of all four Cities in Flight books exists, first published in the United States by Avon (1970), (ISBN 0380009986) and later in the UK by Arrow (1981), (ISBN 0099264404), which includes an analysis of the work (pp. 597 onwards) as an Afterword by Richard D. Mullen, derived from an original article by Leland Shapiro in the publication Riverside Quarterly. It is now available in hardcover and trade paperback from Overlook Press.

Outside the United States, a single volume collecting all four books is available from Gollancz as part of its SF Masterworks series. This edition includes a new (2006) introduction by Stephen Baxter; and uses the original United States title The Triumph of Time for A Clash of Cymbals. The first two were also collected as Cities in Flight, Vol. 1 (1991) and the second two as Cities in Flight, Vol. 2 (1991)

After Such Knowledge

- A Case of Conscience (first section published in If magazine, 1953, expanded version Ballantine 256 1958, Penguin 1966, Arrow 1972), Included in American Science Fiction: Nine Classic Novels of the 1950s Library of America 2012

- Doctor Mirabilis (Faber and Faber 1964, Panther 1976, Avon 1982), about Roger Bacon

- Black Easter (more correctly titled Black Easter, or Faust Aleph-null) (serialized as Faust aleph-null in If magazine 1967, Doubleday 1968, Faber and Faber 1969, Dell 1969, Penguin 1972, Avon SF Rediscovery 27 1977)

- The Day After Judgment (published in Galaxy magazine in 1970, Doubleday 1971, Faber and Faber 1972, Penguin 1974)

- The Devil's Day (Gregg Press 1990, Baen 1990) collects Black Easter and The Day After Judgment

- After Such Knowledge (1991, Legend Books) [omnibus of all 4 books]

The Haertel Scholium

- Galactic Cluster (stories, Signet S1719 1959) — Containing among others "Beep", "Common Time" and "Nor Iron Bars". The book version of the last story combines "Detour to the Stars" (1956) and "Nor Iron Bars" (1957). The 1960 UK hardback removes three stories from the Signet edition and adds "Beanstalk" (1952); the 1963 UK paperback edition removes three stories from the Signet edition (only two of the three are the same as those removed for the 1960 variation); the 1980 UK paperback uses the 1963 contents and adds "Beanstalk".

- So Close to Home (stories, Ballantine 465K 1961)

- The Star Dwellers (G. P. Putnam's Sons 1961, Avon F-122 1962, Faber and Faber 1962, Berkley 1970)

- Mission to the Heart Stars (Faber and Faber 1965, G. P. Putnam's Sons 1965, Panther 1980, Avon 1982) — A sequel to The Star Dwellers

- Welcome to Mars! (G. P. Putnam's Sons 1967, Faber and Faber 1967, Sphere 1978, Avon 1983) — Dolph Haertel's seminal first flight to Mars.

- Anywhen (Doubleday 1970, Faber and Faber 1970, Arrow 1978, Avon 1983) — Contains among others the novella A Traitor of Quality and the short story "A Dusk of Idols" (The 1971 UK edition removes the preface and adds a short story, "Skysign"]

- Midsummer Century (DAW 89 1972) — The Far Future, at the time of Rebirth V. [The 1974 edition adds two unconnected short stories]

- A Case of Conscience — Technically part of the Scholium, thanks to presence of the drive (see above)

Other stories

- "There Shall Be No Darkness" (Thrilling Wonder Stories, 1950) — horror short story where guests at a remote country estate discover that one of them is a werewolf. This was filmed as The Beast Must Die (a.k.a. Black Werewolf) (1974).

- The Warriors of Day (as Sword of Zota 1951, Galaxy 16 1953, Lancer 1967, Avon 1979, Arrow 1979)

- Jack of Eagles (Greenberg 1952, Galaxy 19 1953, as ESPer Avon T-268 1958, Avon 1968, Faber and Faber 1973, Arrow 1975)

- "Get Out of My Sky" (novella, 1957)

- Fallen Star (Faber and Faber 1957) (also published as The Frozen Year Ballantine 197 1957) — Set in the International Geophysical Year of 1958, it tells the story of a disaster-ridden polar expedition that finds a meteorite containing fossil life forms.

- VOR (Avon T-238 1958, Arrow 1979) [expanded by Blish from the collaborative 'The Weakness of RVOG' [with Damon Knight], {Thrilling Wonder Stories}, Feb 1949]

- Titans' Daughter (Berkley G507 1961, Four Square 1963, Avon 1981) (expanded from "Beanstalk" (in Future Tense, ed. K. F. Crossen, 1952)

- The Night Shapes ( Ballantine F647 1962)

- The Duplicated Man (with R. W. Lowndes, Avalon 1959, Airmont 8 1964)

- A Torrent of Faces (with Norman L. Knight, Doubleday 1967, Ace Special A-29 1968)

- The Vanished Jet (Weybright and Talley 1968)

- And All the Stars a Stage (Doubleday 1971, Faber and Faber 1972, Avon 1974)

- The Quincunx of Time (Dell 1973, Faber and Faber 1975, Avon 1983) expansion of "Beep" (Galaxy, Feb 1954)

Star Trek

- Star Trek (Bantam 1967; later as Star Trek 1) Collections of adaptations of the scripts of the well-known TV series

- Star Trek 2 (Bantam 1968)

- Star Trek 3 (Bantam 1969)

- Spock Must Die! (Bantam 1970) The first Star Trek novel for an adult audience

- Star Trek 4 (Bantam 1971)

- Star Trek 5 (Bantam 1972)

- Star Trek 6 (Bantam 1972)

- Star Trek 7 (Bantam 1972)

- Star Trek 8 (Bantam 1972)

- Star Trek 9 (Bantam 1973)

- Star Trek 10 (Bantam 1974)

- Star Trek 11 (Bantam 1975)

- Star Trek 12 (Bantam 1977) [with Judith Ann Lawrence]

[Books 2, 3 and 8 were combined as The Star Trek Reader (1976). Books 1, 4 and 9 were combined as The Star Trek Reader II (1977). Books 5, 6 and 7 were combined as The Star Trek Reader III (1977). Books 10, 11 and Spock Must Die! were combined as The Star Trek Reader IV (1978)]

- Star Trek: The Classic Episodes 1 (with Judith Ann Lawrence) (Bantam 1991) (27 of the adapted screenplays arranged in order of transmission)

- Star Trek: The Classic Episodes 2 (with Judith Ann Lawrence) (Bantam 1991) (25 of the adapted screenplays arranged in order of transmission)

- Star Trek: The Classic Episodes 3 (with Judith Ann Lawrence) (Bantam 1991) (24 of the adapted screenplays arranged in order of transmission)

Other collections

- The Seedling Stars (Gnome 1957, Signet S1622 1959, Faber and Faber 1967)

- Best Science Fiction Stories of James Blish (stories, Faber and Faber 1965). It includes There Shall Be No Darkness; the revised 1973 edition removes There Shall Be No Darkness and adds 2 stories from the late 1960s; this revised version was published by Arrow Books in 1977 as The Testament of Andros.

- A Work of Art and other stories (edited by Francis Lyall;) Severn House 1993)

- A Dusk of Idols and other stories (edited by Francis Lyall; Severn House 1996)

- Works of Art NESFA (edited by James Mann, introduction by Gregory Feeley; NESFA 2008)

- Flights of Eagles (edited by James Mann, foreword by Tom Shippey; NESFA 2009)

Anthologies

- New Dreams This Morning (1966)

- Nebula Award Stories No. 5 (1970)

- Thirteen O'Clock and other zero hours (collection of C. M. Kornbluth stories; edited by Blish; 1970)

Non-fiction

Blish wrote criticism of science fiction—some quite scathing—under the name of William Atheling, Jr. (derived from a pseudonym Ezra Pound used for music criticism), as well as reviewing under his own name. The Atheling articles were reprinted in two collections, The Issue at Hand (1964) and More Issues at Hand (1970), and the posthumous The Tale That Wags The God (1987) collects Blish essays.

He was a fan of the works of James Branch Cabell, and for a time edited Kalki, the journal of the Cabell Society.

Reviewing The Issue at Hand, Algis Budrys described "Atheling" as "acidulous, assertive, categorical, conscientious and occasionally idiosyncratic."[11]

Honors, awards and recognition

Soon after his death there was a 1976 BSFA Special Award to Blish for Best British SF.

The British Science Fiction Foundation inaugurated the James Blish Award for SF criticism in 1977, recognizing Brian W. Aldiss, "but it then lapsed for lack of funds".[12]

The Science Fiction and Fantasy Hall of Fame inducted him in 2002.[13]

- 1959 Hugo Award for A Case of Conscience "Best Novel"[9]

- 1960 Guest of Honor, World Science Fiction Convention

- 1965 Nebula Award nomination for "The Shipwrecked Hotel" "Best Novelette" (with Norman L. Knight)

- 1968 Nebula Award nomination for Black Easter "Best Novel"

- 1969 Hugo Award nomination for "We All Die Naked" "Best Novella"

- 1970 Nebula Award nomination for "A Style in Treason" "Best Novella"

- 1970 Guest of honor, British Eastercon

- 1950/2001 Retro-Hugo Award nomination for "Okie" "Best Novelette"

- 1953/2004 Retro-Hugo Award for "Earthman Come Home" "Best Novelette"

- 1953/2004 Retro-Hugo Award for "A Case of Conscience" "Best Novella"[9]

References

- ↑ Bloom, Harold. "James Blish: 1921-1975", Science fiction writers of the golden age, p. 63. Chelsea House, 1995. ISBN 0-7910-2199-8. "James Blish 1921-1975 James Benjamin Blish was born on May 23, 1921, in East Orange, New Jersey, the only child of Asa Rhodes Blish and Dorothea Schneewind Blish."

- ↑ "Futurians". Fancyclopedia 3. Retrieved July 26, 2013.

- ↑ James Blish at the Internet Speculative Fiction Database (ISFDB). Retrieved 2013-04-08. Select a title to see its linked publication history and general information. Select a particular edition (title) for more data at that level, such as a front cover image or linked contents.

- ↑ Science Fiction Citations, Citations for gas giant n.

- ↑ "1380I James Benjamin Blish, B.Sc., Ed. (***) [m]".

- ↑ "Collection Level Description: Books and Papers of James Blish". Retrieved October 15, 2013.

- ↑ Choosing AD 4004 is a satirical reference to the year "4004 BC", inferred by Bishop James Ussher to be the year of the creation of the universe, based on his study of the Book of Genesis.

- ↑ Perakos, Peter S. (June 1979). "John Flory's Monument: An SF Saga in the Works". Starlog (23).

- 1 2 3 "Blish, James". The Locus Index to SF Awards: Index to Literary Nominees. Locus Publications. Retrieved 2013-04-08.

- ↑ Blish, James (1957). Year 2018! (First Avon edition ed.). 575 Madison Avenue--New York 22, NY: Avon Publications, Inc.

- ↑ "Galaxy Bookshelf", Galaxy, June 1965, pp.168-69. Reprinted in Benchmarks: Galaxy Bookshelf, Southern Illinois University Press, 1985.

- ↑ "Blish, James". The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. Online third edition 2011–2012. Retrieved 2013-03-22.

- ↑ "Science Fiction and Fantasy Hall of Fame". Mid American Science Fiction and Fantasy Conventions, Inc. Retrieved 2013-03-22. This was the official website of the hall of fame to 2004.

Citations

- Tuck, Donald H. (1974). The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction and Fantasy. Chicago: Advent. pp. 51–53. ISBN 0-911682-20-1.

- Tymn, Marshall B.; Kenneth J. Zahorski; Robert H. Boyer (1979). Fantasy Literature: A Core Collection and Reference Guide. New York: R.R. Bowker Co. pp. 52–54. ISBN 0-8352-1431-1.

Further reading

- Imprisoned in a Tesseract, the life and work of James Blish by David Ketterer ISBN 0-87338-334-6

- Fantasy and Science Fiction (April 1972) — "Special James Blish Issue"

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: James Blish |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to James Benjamin Blish. |

- Official author website

- Bibliography

- Genealogy

- James Blish Appreciation

- Works by James Blish at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about James Blish at Internet Archive

- Works by or about William Atheling at Internet Archive

- Works by James Blish at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Works by James Blish at Open Library

- James Blish at the Internet Speculative Fiction Database

- James Blish at the Internet Book List

- James Blish at Memory Alpha (a Star Trek wiki)

- "James Blish biography". Science Fiction and Fantasy Hall of Fame.

- James Blish at Goodreads

- James Blish at the Internet Movie Database