White River War

| White River War | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Ute Wars, American Indian Wars | |||||||

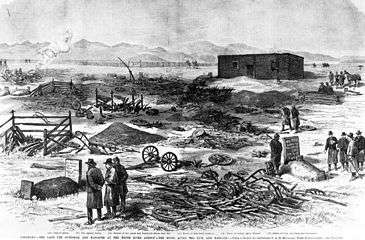

An etching that appeared in the December 6, 1879 edition of "Frank Leslie's Weekly" depicts the aftermath of the Meeker Massacre. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

| Ute | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

Ouray Nicaagat (Jack) | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| ~700 | ~250 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

24 killed 44 wounded |

19–37 killed 7 missing | ||||||

The White River War, also known as the Ute War, or the Ute Campaign,[1] was fought between the White River Utes and the United States Army in 1879, resulting in the forced removal of the White River Utes and the Uncompahgre Utes from Colorado,[2] and the reduction in the Southern Utes' land holdings within Colorado. The war signalled the final defeat of the Utes and opened millions of new acreage to settlement.[3]

War

The conflict began when Major Thomas T. Thornburgh led a command of 153 soldiers, and twenty-five militiamen, to the White River Agency, in response to a request for assistance by the Indian Agent Nathan C. Meeker. Meeker had been attempting to convert the White River Utes to agriculture and Christianity, and had angered the Utes by plowing a field they used to graze and race horses. After an altercation with some Utes, Meeker had sent to the army for assistance.[4]

The main incidents of the war took place on September 29, 1879. Major Thornburgh advanced with his command across Milk Creek onto the White River Ute land, despite assuring several Utes on previous days that the main body of his command would remain off the reservation. An Ute force, led by Nicaagat (Jack), were hidden on high ground prepared to defend their territory. The competing armed forces signalled each other, with both sides meaning to meet with each other peacefully, when an errant shot began what came to be known as the Battle of Milk Creek. The Utes, although outnumbered, held the strategic high ground, and managed to hold the American army forces at bay, and inflict significant losses, including the death of Major Thornburgh and thirteen others, wounding more than forty.

Meanwhile, a separate group of Utes, descended upon the White River Agency and killed ten male employees and Nathan Meeker. They also took three women and two children captive in what became known as the Meeker Massacre.[5]

The United States Cavalry remaining at Milk Creek were in disarray, corralled with most of their animals dead and being used as defensive barricades. They were under the command of Captain J. Scott Payne, who sent out messengers for reinforcements. The troops held out for two days until the arrival of Captain Francis S. Dodge and his company of Buffalo Soldiers from Fort Lewis in southern Colorado. These reinforcements helped the army hold their position until Colonel Wesley Merritt arrived with close to 450 troops, this led to the Utes' withdrawing from the battle after six days of fighting.[6]

The army suffered thirteen casualties, including ten soldiers and three militiamen killed, and forty-four wounded, five of whom were of the militia. The Utes had suffered a total of thirty-seven fatalities, in both the battle and the massacre.[7]

Aftermath

After the Milk Creek and White River incidents, there was intense hostility toward the Utes, both within Colorado and the American army, and mounting pressure to drive them entirely from the state, or to exterminate them altogether.[8] There had already been a desire to move the Utes off their land prior to the outbreak of the war so the fighting added fuel to the fire.[9]

The treaty negotiations were the result of the intercession of Secretary of the Interior Carl Schurz, who stopped any movement of forces against the Ute until such time as the hostages were safely released. Former Indian agent Charles Adams, who had previously served at White River, managed to secure the hostages' release by the White River Utes.[10] Schurz was accompanied during his trip to Colorado for those negotiations by a young German diplomat named August von Dönhoff, the father of Marion Gräfin Dönhoff, a well known German journalist and Anti-Nazi resistance fighter.[11]

The official ceding of Ute land occurred after negotiations that began in November 1879 with a Peace Commission at the Los Pinos Agency. After this commission failed to produce results, Congress summoned the participants to Washington in 1880. A treaty was agreed upon where the White River Utes agreed to be removed to Uintah Reservation in Utah, and the Uncompahgre Utes, who had not participated in the uprising, were to remain in Colorado, but on a smaller parcel of land.[12] Later this plan was changed, and the Uncompahgre Utes too were removed to Utah.[13] The Southern Ute were also to be moved, although it proved difficult to find them land in neighboring states. Ultimately they remained on a reservation along the border of Colorado and New Mexico.[14]

After removal the Uncompahgre Utes named their new land reserve Ouray Reservation after the late Chief Ouray, who died in August 1880, occurred on August 28, 1881. The Uncompahgres were moved under the accompaniment of the army, commanded by Colonel Ranald MacKenzie. The army was used to force the Utes to move, but it also served to protect the Utes from the wrath of the settlers who followed the exodus of the Uncompahgres.[15]

The White River Utes were more difficult to move. The Indian Bureau lured them to the Uintah Reservation by sending their rations and land compensation payments there.[16] The White River Utes remained largely nomadic, and remained a threat to return to Colorado. For that reason, the army, with the aid of the Interior Department, planned a military post next to the Utah reservations. When Jack and the White River Utes fled back to Colorado, the army tracked down and located them on April 28, 1882. Soldiers killed him while he was trying to avoid capture and being forced to return to Uintah Reservation.[17] The removal of the Utes from most of their lands in Colorado effectively marked the end of the White River War.

Notes

- ↑ http://www.cgsc.edu/carl/resources/csi/santala/santala.asp#m1

- ↑ David Rich Lewis, Neither Wolf nor Dog: American Indians, Environment, and Agrarian Change (New York: Oxford University Press, 1994), 48.

- ↑ Dee Brown, Bury my Heart at Wounded Knee: An Indian History of the American West (New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston, 1971), 387-89.

- ↑ Peter R. Decker, "The Utes Must Go!": American Expansion and the Removal of a People, (Golden, CO: Fulcrum Publishing, 2004), pp. 115-19.

- ↑ Jerry Keenan, "Meeker Massacre," in Encyclopedia of American Indian Wars: 1492-1890, (Santa Barbara: ABC-Clio, 1997).

- ↑ Decker, "The Utes Must Go!", pp. 141-144.

- ↑ Decker, "The Utes Must Go!", 219, #27.

- ↑ Decker, "The Utes Must Go!", 145-50.

- ↑ Brown, Bury my Heart, 376-77.

- ↑ Decker, "The Utes Must Go!", 150-51

- ↑ Kindheit in Ostpreußen (Before the Storm: Memories of My Youth in Old Prussia), translated by Jean Steinberg, foreword by George F. Kennan, 1990, ISBN 0-394-58255-1

- ↑ Decker, "The Utes Must Go!", 163.

- ↑ Decker, "The Utes Must Go!", 180-87.

- ↑ Decker, "The Utes Must Go!", 163, 176-78.

- ↑ Decker, "The Utes Must Go!", 187-89.

- ↑ Decker, "The Utes Must Go!", 185.

- ↑ Decker, "The Utes Must Go!", 190-93.

Bibliography

- Lewis, David (1997). Neither Wolf nor Dog. Oxford Oxfordshire: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-511794-8.

- Decker, Peter R. (2004). The Utes Must Go!. Golden: Fulcrum Publishing. ISBN 1-55591-465-9.

- Brown, Dee (2001). Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee. New York: H. Holt. ISBN 0-8050-6634-9.