West Oakland, Oakland, California

Coordinates: 37°48′43″N 122°17′42″W / 37.81194°N 122.29500°W

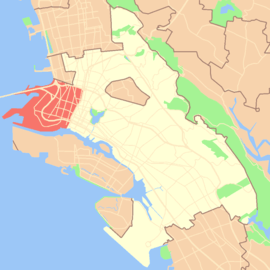

West Oakland is a neighborhood situated in the northwestern corner of Oakland, California, along the waterfront near the Port of Oakland and the San Francisco–Oakland Bay Bridge. It lies at an elevation of 13 feet (4 m).

History

The land which comprises part of West Oakland was granted to Luis Maria Peralta in 1820. In the 1850s, a group of men who had been leasing the land from his son Vicente, Horace Carpentier, Edson Adams, and Andrew J. Moon, began illegally selling small farm plots west of what is now Market Street.[1] One of the squatters, Horace Carpentier became Oakland's first mayor in 1854. The population grew after 1863, when the San Francisco-Oakland railroad connected central Oakland to the San Francisco bay ferries. In 1869, West Oakland became the terminus of the transcontinental railroad, and the population grew again as railroad workers settled in the neighborhood.

In the 1880s and 1890s, a large number of shops and small and medium-sized houses were built to accommodate the large number of European Americans, African Americans, Portuguese, Irish, Mexicans, Japanese, and Chinese immigrants who settled in West Oakland. Many African Americans were employed as porters for the Pullman Palace Car Company, and the headquarters of their union, the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, was at 5th and Wood Streets. The writer Jack London lived in West Oakland in the late 19th century, and his novel Valley of the Moon is set in West Oakland. Many of the houses built in that period are still standing today and make up the quaint character of the neighborhood. Oakland's baseball team, the Oakland Oaks, played at the Oakland Baseball grounds West Oakland in 1879. In 1906, many people left homeless by the 1906 San Francisco earthquake settled in West Oakland. The original wooden train station at 16th and Wood Streets was replaced in 1912 by a large Beaux Arts structure which is still standing, though it was severely damaged in the 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake.

World War I brought new job opportunities in the shipyards and with it an influx of workers and business growth. By 1930, West Oakland was a thriving, predominately African-American neighborhood of about 2800 residents. Seventh Street was lined with jazz and blues clubs. Marcus Garvey's Universal Negro Improvement Association had its West Coast headquarters at 8th and Chester Streets.

West Oakland experienced a decline in the Depression in the late 1930s, and some residential areas became dilapidated. In the 1940s and 1950s, dozens of blocks were bulldozed and replaced with public housing projects. The 1940s and World War II saw a new influx of workers for the shipbuilding industry and the newly constructed Oakland Army Base and Naval Supply Center.

As the railroads declined and Americans turned to the automobile for transportation in the 1950s, many employees moved away. When the Cypress Freeway, a double-decker freeway connecting the San Francisco–Oakland Bay Bridge with the Nimitz Freeway, was built in the 1950s above Cypress Street, it effectively split the neighborhood in half and isolated it from downtown Oakland. In the late 1960s and early 1970s, block after block was razed and thousands of residents were displaced for the building of the massive Oakland Main Post Office, the West Oakland BART Station, and the Acorn Plaza housing project. These projects coincided with a period of economic decline characterized by unemployment, poverty, and urban blight.

West Oakland was also home to the first Mexican and Latino community in Oakland. Fleeing the Mexican Revolution, Mexicans started settling in West Oakland in the 1910s. Mexican and Puerto Ricans also settled in West Oakland to work on the railroads, at the port, and in industry, and opened many local businesses. In World War II the Latino community grew as Mexicans from the Southwestern United States settled in West Oakland to work in wartime industries Also 5000 Braceros came to Oakland to work in the Southern Pacific Railroad West Oakland yard. In the 1950s and 1960s, urban renewal, construction of the Nimitz Freeway, and BART displaced most of the Latino community which settled in the Fruitvale and East Oakland areas. West Oakland became a primarily African American neighborhood, with a small Hispanic population. [2]

Groups of African American residents of West Oakland mobilized to resist the "urban renewal" projects during this period. The Black Panthers grew out of this resistance and West Oakland became the center of the Black Panthers in the late 1960s. Their main office was on Peralta Street, and they distributed free breakfasts to children in St. Augustine's church on West Street. DeFremery Park was the site of Black Panther rallies and social programs. Huey P. Newton was convicted of manslaughter after allegedly shooting an officer on 7th Street, and Newton himself was killed in 1989 by a drug dealer in West Oakland. The east end of the Transbay Tube is located in West Oakland.

1989 Loma Prieta earthquake to the present

In the Loma Prieta earthquake of 1989, the Cypress Freeway collapsed. 42 people were killed despite rescue efforts by West Oakland residents. West Oakland residents successfully resisted efforts to rebuild the freeway in the same location. With the freeway now removed, West Oakland started to undergo gentrification. Cypress Street was renamed Mandela Parkway, a recently finished wide thoroughfare with a pedestrian path and greenway in its median, including a park commemorating the 1989 earthquake. It is lined with condominiums and new and established businesses. Several of the surrounding warehouses now serve as artist studios. Most notably the former seven acres of facilities for American Steel are now Big Art Studios, a unique facility for large-scale artists. Several pieces of work by the constituent art groups within can be found on display outside the complex. Mandela Gateway, a mixed retail and residential development at the south end of Mandela Parkway, surrounds the West Oakland BART station. The old Victorian houses are being refurbished, and new construction is springing up. The new Central Station project has brought Zephyr Gate, a 130-unit condominium development, and the Pacific Cannery Lofts, a 163-unit development to the area around the train station.[3] The growth of Emeryville on the border of West Oakland, West Oakland's proximity to San Francisco via the San Francisco–Oakland Bay Bridge and BART, and the more affordable rental and home prices, have attracted many new residents.

Neighborhoods

West Oakland consists of the following neighborhoods:

- Acorn Industrial

- Acorn Projects

- Campbell Village Court

- Cypress Village

- Clawson

- Desert Yard

- Dogtown

- Ghostown

- Hoover/Foster

- Lower Bottoms

- McClymonds

- Oak Center

- Oakland Naval Supply Depot

- Oakland Point

- Prescott

- Port of Oakland

- Ralph Bunche

- South Prescott

Air pollution

West Oakland is exposed to a disproportionate amount of airborne toxins, as compared to the rest of the surrounding Alameda County. West Oakland’s close proximity to highways and the Port of Oakland leave residents highly exposed to pollutants caused by moving and stationary sources of diesel pollution, thus leaving them at higher risk for health complications such as asthma and even shorter life expectancy than surrounding neighborhoods averages.[4]

Non-profit organizations

- City Slicker Farms is an urban agriculture non-profit 501(c)3 organization established in West Oakland in 2001 to address the food access needs of West Oakland residents. They operate the Community Market Farms, Backyard Garden, and Urban Farming Education programs, aimed at empowering West Oakland community members to meet the basic need for fresh, healthy food by creating sustainable, high-yield urban farms and backyard gardens.

- Urban Releaf is an urban forestry non-profit 501(c)3 organization established in West Oakland in 1998 to address the needs of communities that have little to no greenery or tree canopy. They focus their efforts in under-served neighborhoods that suffer from disproportionate environmental quality of life and economic depravity.

- The Crucible is a 501 (c)(3) nonprofit industrial arts education facility in West Oakland who fosters a collaboration of arts, industry, and community. From metal fabrication, blacksmithing, neon, glass blowing, ceramics, welding, kinetics, and fire dancing, The Crucible provides arts education programs to over 5,000 adult and youth students annually.

- Prescott-Joseph Center for Community Enhancement has served the West Oakland community since 1995. Housed in a former convent building at 920 Peralta Street, the Center provides family support services, arts and cultural programs (including art shows and theatrical events in the summer), health care initiatives (such as the first Northern California Breathmobile), and youth enrichment programs. The Prescott-Joseph Center partners with many local schools, community-based organizations and artists.

- Mandela Marketplace is a non-profit organization that works in partnership with local residents, family farmers, and community-based businesses to improve health, create wealth, and build assets through cooperative food enterprises in low income communities.

- Seminary of the Street seeks to cultivate a movement of "love warriors" in resistance to every form of violence and deathliness and in the service of the flourishing of all life. Their headquarters, WORSHP House, at 1724 Filbert Street, is also an intentional community and forms the nucleus of the organizations's West Oakland Reconciliation and Social Healing Project and its associated Alternatives to Gentrification Program.

- Urban Biofilter A community-based non-profit focussing on designing, planning, and advocating for ecosystem services infrastructure solutions to industrial emissions.

References

- ↑ Bagwell, Beth. Oakland, The Story of a City, 1996, Oakland Heritage Alliance, 2nd ed.

- ↑ Oakland Museum Latino History project http://www.museumca.org/LHP/

- ↑ http://www.welcomeaboard.com Central Station: A Bay Area Destination

- ↑ Pastor, Manuel. "Still Toxic After All These Years" (PDF). Bay Area Environmental Health Collaborative. Retrieved 30 April 2014.

Further reading

- Bagwell, Beth, Oakland The Story Of A City, Oakland Heritage Alliance, 2nd ed., 1996

- Putting the "There" There: Historical Archaeologies of West Oakland]