Camisard

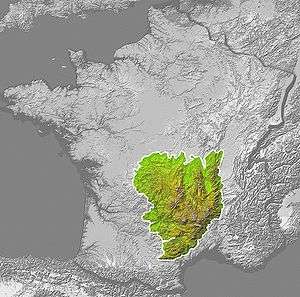

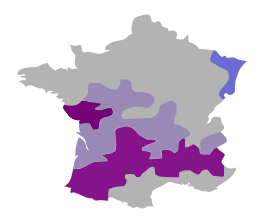

Camisards were Huguenots (French Protestants) of the rugged and isolated Cévennes region, and the Vaunage in southern France. They raised an insurrection against the persecutions which followed the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes in 1685, which had made being Protestant illegal. The Camisards operated throughout the mainly protestant Cévennes region which in the eighteenth century also included the Vaunage and the parts of the Camargue around Aigues Mortes. The revolt by the Camisards broke out in 1702, with the worst of the fighting continuing until 1704, then scattered fighting until 1710 and a final peace by 1715. The Edict of Tolerance was not finally signed until 1787.

Etymology

The name camisard in the Occitan language can attributed to a type of linen smock or shirt known as a camisa (chemise) that peasants wear in lieu of any sort of uniform. Alternatively, it can derive from the Occitan word camus, meaning paths (chemins). Camisada, in the sense of "night attack", is derived from a feature of their tactics.[1]

History

In April 1598, Henry IV had signed the Edict of Nantes and the religious wars that had ravaged France ended. Protestants had been given limited civic rights and the liberty to worship according to their convictions. This "fundamental and irrevocable law" was maintained by Henry's son, Louis XIII. In October 1685, Henry's grandson, Louis XIV (The Sun king), revoked the Edict of Nantes, issuing his own Edict of Fontainebleau. Louis was determined to impose a single religion on France: that of Rome. As early as 1681 he instituted the dragonnades which were conversions enforced by dragoons, labelled "missionaries in boots". They were billeted in the homes of Protestants to help them decide to convert back to the official church or alternatively to emigrate. The Cévennes was a centre of resistance, and the policy did not work.[2]

The Edict of Fontainebleau removed all rights and protections from the Huguenots. There followed about twenty years of persecutions. Reformed worship and private Bible readings were outlawed. Within weeks of the new edict over 2000 protestant churches were fired, under the direction of Nicholas Lamoignon de Basville, the royal administrator of Languedoc, and entire villages were massacred and burnt to the ground in a series of stunning atrocities. The pastors and worshippers were captured and later exiled, sent to the galleys, tortured or killed. Seventy-five missionary priests under the command of Abbot François Langlade were sent to the Cévennes. Soldiers carrying crosses on their muskets forced the peasants to sign papers to say they were converting, and forced them to attend mass. The peasants continued to attend illicit meeting. Huguenots with a trade, fled to neighbouring countries. The King responded by closing the borders.[2]

The protestant peasants of the Vaunage and the Cevennes, led by a number of teachers known as "prophets", notably Franćois Vivent and Claude Brousson, resisted. Vivent encouraged his follower to arm themselves in case they were set upon by Royalist soldiers. Several leading prophets were tortured and executed, Franćois Vivent in 1692 and Claude Brousson in 1698. Many more were exiled, leaving the abandoned congregations to the leadership of less educated and more mystically-oriented preachers, such as the wool-comber Abraham Mazel. The Catholic church was likened to the Beast of the Apocalyse and the clandestine prophets claimed to have seen it in the prophetic dreams. Mazet, in a dream, saw black oxen in his garden and heard a voice telling him to chase them away. From 1700 the clandestine prophets and their armed followers were hidden in houses and caves in the mountains. [2] [3]

Abraham Mazet

Open hostilities began on 24 July 1702, with the assassination at le Pont-de-Montvert of a local embodiment of royal oppression, François Langlade, the Abbé of Chaila. Langlade had recently arrested and tortured a group of seven Protestants accused of attempting to flee France.[4] The band of Camisards were led by Abraham Mazet who peacefully asked for the release of the prisoners, but when this was refused they commenced the slaughter.[5] The abbé was quickly lionized in print by the Catholic State as a martyr of his faith.

The Camisards worked independently of each other and during the day most merged back into their village communities. They were predominantly agricultural workers or artisans and had no aristocratic leaders. They knew the paths and the sheep tracks intimately. They called themselves the Children of God- they were inspired by religion not by patronage or politics.

Jean Cavalier

Led by the young Jean Cavalier and Pierre Laporte (Rolland), the Camisards met the ravages of the royal army with irregular warfare methods and withstood superior forces in several pitched battles.[6]

Violence increased as atrocities were committed on both sides : massacres in Catholic villages such as Fraissinet-de-Fourques, Valsauve and Potelières by camisards. Basville, a government administrator with a reputation founded on torture, deported the entire populations of Mialet and Saumane. Then in the autumn of 1703 , with the king’s consent, the systematic « Burning of the Cévennes » destroyed 466 hamlets and exiled their populations.[1]

Other Protestants, like those of Fraissinet-de-Lozère, under the influence of village elites, chose a loyalist attitude and fought the Camisards. They were nevertheless equally victims, losing their homes, during the "Burning of the Cévennes".[7]

White Camisards, also known as "Cadets of the Cross" ("Cadets de la Croix", from a small white cross which they wore on their coats), were Catholics from neighbouring communities such as St. Florent, Senechas and Rousson who, on seeing their old enemies on the run, organized into companies to loot and to hunt the rebels down.[1] They committed atrocities, such as killing 52 people at the village of Brenoux, including pregnant women and children.

Other opponents of the Protestants included six hundred miquelet marksmen from Roussillon hired as mercenaries by the King.

In 1704, Claude Louis Hector de Villars, the royal commander, offered vague concessions to the Protestants and the promise to Cavalier of a command in the royal army. Cavalier's acceptance of the offer broke the revolt, although others, including Laporte, refused to submit unless the Edict of Nantes was restored. Scattered fighting went on until 1710, but the true end of the uprising was the arrival in the Cévennes of the Protestant minister Antoine Court and the reestablishment of a small Protestant community that was largely left in peace, especially after the death of Louis XIV in 1715.

The people

42% of the Camisards were Cévennes peasants, and 58% were rural craftsmen, of whom 75% worked as wool-combers, wool-carders and weavers. All spoke Occitan. There were no noblemen involved, none had been trained in the art of war. There was no concept of a single army, there was no single leader but every region had its permanent organisers and occasional soldiers.[1]

The leaders of note were:

- Gédéo Laporte

- Salomon Couderc with Abraham Mazel in Le Bougès and Mont Lozère.

- Henri Castanet (1674-1705) in charge of Mont Aigoual.

- Pierre Laporte (Rolland) (1680-1704) in the Basses-Cévennes, Mialet and Lassalle.

- Jean Cavalier (1681-1704) in the plains of Bas-Languedoc between Uzès and Sauve.[1]

Religiously, ordained pastors were rounded up, and a series of prophets ministered secretly. Notable among them were:

- Esprit Séguier

- Abraham Mazel

- Elie Marion

- Jean Cavalier

The prophets visions inspired the operations of the war, and inspired the peasants to feel invincible. The peasants marched singing Psalms- which unnerved the opposition. [1]

The events

1701

- June the Vallérargues affair, when the people seized back captured prophets from priests.[4]

1702

- 24 July assassination of François Langlade, Abbé du Chayla, two priests and catholic family at Dévèze

- 12 August Execution of Esprit Séguier. Traditional start of the War.

- 11 September Battle at Champdomergue, a hill near (Le Collet-de-Dèze) with no clear outcome

- 22 October Battle at Témélac. Gédéon Laporte killed and his head displayed at Barre-des-Cévennes, Anduze, Saint-Hippolyte and Montpellier.

- 24 December Jean Cavalier took the 700 strong garrison town of Alès. He led 70 Camisards

- 28 December The Camisards took Sauve [4][8]

1703

- 12 January Jean Cavalier took Val de Barre (Nimes) from royalist Count de Broglie.

- February Count de Broglie relieved of his duties and replaced by Field-Marshal de Montrevel. More troops deployed.

- 26 February The Camisards under Castenet massacred the inhabitants of Fraissinet-de-Fourques

- 6 March Battle of Pompignan- the Camisards lost

- 1 April The royalist Moulin de l’Agau massacre

- April the deportation of Mialet and Saumane to Perpignan in Roussillon

- 29 April Jean Cavalier defeated at Tour de Billot (Alès)

- 18 May Battle of Bruyès

- 12 September massacre of Catholics at Potelières

- 20 September massacre of Catholics at Saturargues (Lunel) and Saint-Sériès

- Autumn The Burning of the Cévennes policy-villagers were deported from 466 villages which were then torched

- Autumn emergence of the Catholic Cadets of the Cross (White Camisards) who looted and pillaged

- 20 December Battle of the Madeleines (Tornac)[4][8]

1704

- 15 March the battle of Devès de Martignargues (Vézénobres). Jean Cavalier defeated a catholic regiment

- March Field-marshal de Montrevel was relieved of his duties and replaced by Field-marshal de Villars.

- 16 April de Montrevel defeated Cavalier at the Battle of Nages (while waiting for de Villars arrival)

- 19 April Cavalier's stores discovered in caves at Euzet

- 20 April de Villars assumes command and suggests negotiation

- May negotiation start, Cavalier accepts unconditional surrender and a command in the royal army

- 13 August Pierre Laporte (Rolland) dies at Castelnau-les-Valence

- October Other leaders leave France.[4]

Heritage

Jean Cavalier later went over to the British, who made him Governor of the island of Jersey.

A millenarian group of ex-Camisards under the guidance of Elie Marion emigrated to London in 1706, and were said to have links with the Alumbrados. They were generally treated with scorn and some official repression as the "French Prophets". Their example and their writings had some influence later, both on the spiritual outlook of Jean-Jacques Rousseau and on Ann Lee, founder of the Shaker movement.

Role in the survival of Protestantism in France

After the main active camisard groups had been subdued in various ways, the French authorities were keen not to re-ignite the revolt and took a much moderate approach to anti-protestant repression. Many former camisards came back to a more peaceful approach and from 1715 onwards helped re-establish a still illegal but now much better organised Protestantism. They were under the leadership of Antoine Court and of the numerous travelling pastors who were permitted to re-enter the country.[9]

"The Camisards' legend"

In his book with this title[10] history professor, Philippe Joutard, registered the very lively oral tradition about the camisards which has prevailed to this day in the Cévennes region. He also observed the "attractive power" of this very striking period of history where many unrelated episodes have been integrated through the oral tradition. As this oral transmission is mainly done through the families, it often highlights more of their own ancestors who were faithful to their convictions than the heroic leaders of the revolt. In so doing it develops beyond the original religious question to a general attitude of resistance and non-conformity which determines a whole philosophical, political and human culture and way-of-life.[11] Philippe Joutard also noted that even the arch-minority of Catholics living in this protestant part of the country tend to reconstruct their history in the same way as their former religious opponents.[11] The footprint of the camisards in Cévennes is thus particularly deep and lasting.

See also

Notes and references

- Notes

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Bersier 2016.

- 1 2 3 Schlegel 2008.

- ↑ Antoine Court de Gébelin (2009), Histoire des troubles des Cévennes ou de la guerre des camisards sous le règne de Louis le Grand, reprint of the original text printed in 1760. Editions Lacour-Ollé, Nîmes (in French).

- 1 2 3 4 5 Rolland, Pierre. "La Guerre des Camisards". Camisards.net. 48160 St-Martin-de-Boubaux: Association d'étude et de recherche sur les camisards. Retrieved 30 August 2016.

- ↑ Pierre-Jean Ruff, 2008. Le Temple du Rouve: lieu de mémoire des Camisards. Editions Lacour-Ollé, Nîmes.Website Le Temple du Rouve, the first Camisards and freedom of conscience

- ↑ Ana Eliza Bray (1870), The Revolt of the Protestants of the Cevennes, with some account of the Huguenots in the seventeenth century. John Murray, London.

- ↑ Ghislain Baury, La dynastie Rouvière de Fraissinet-de-Lozère. Les élites villageoises dans les Cévennes protestantes d'après un fonds d'archives inédit (1403-1908), t. 1: La chronique, t. 2: L'inventaire, Sète, Les Nouvelles Presses du Languedoc, 2011, http://sites.google.com/site/dynastierouviere/

- 1 2 3 Bersier, Eugène. "The progress of the war 1702-1704". Virtual Museum of Protestantism. Fondation pasteur Eugène Bersier. Retrieved 30 August 2016.

- ↑ Philippe Joutard, Les Camisards, Gallimard 1976, rédité en coll. Folio Histoire en 1994, pp.217-219

- ↑ Philippe Joutard, La Légende des Camisards, NRF Gallimard, 1977

- 1 2 Philippe Joutard, La Légende des Camisards, NRF Gallimard, 1977, p. 355

- References

- Bersier, Eugène. "The Camisards". Virtual Museum of Protestantism. Fondation pasteur Eugène Bersier. Retrieved 29 August 2016.

- Schlegel, Doug (2008). "The Camisards". Leben: A journal of Reformation Life. 4 (4). Retrieved 21 September 2016.

Further reading

Although most of the sources are in French and remain untranslated there are a number of excellent sources available in English:

- Alexandre Dumas, Massacres of the South (1551-1815):Celebrated Crimes, Full text (ebook) 192pp, Retrieved 21 September 2016 ISBN 1-40695-136-6

- H. M. Baird (1895), Huguenots and the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes ISBN 1-59244-636-1

- Napoléon Peyrat (1842). History of the Desert Fathers: from the revolution of the Edict of Nantes to the French Revolution, 1685-1789.

- Robert Louis Stevenson (1879), Travels with a Donkey in the Cévennes. Travel literature.

- Samuel Rutherford Crockett (1903), Flower-o'-the-Corn. Historical fiction.†

† The story begins with the allied armies at Namur following the 1704 Battle of Blenheim, before the scene shifts to the Causse du Larzac (Chapter IV).

External links

| Look up Camisard in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Camisard. |

- A full history of the Camisards (in French with some sections also in English).

- Regordane Info - The independent portal for The Regordane Way or St Gilles Trail (in English and French)

- A memorial devoted to the first Camisards at the temple of Le Rouve in the Cevennes