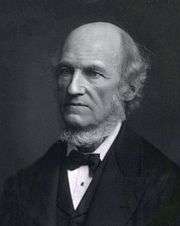

William Benjamin Carpenter

| William Benjamin Carpenter | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

29 October 1813 Exeter, Devon, England |

| Died |

19 November 1885 (aged 72) London, England |

| Cause of death | Burns from an accident with the fire heating a vapour bath |

| Resting place |

Highgate Cemetery 51°34′01″N 0°08′49″E / 51.567°N 0.147°E |

| Nationality | British |

| Alma mater | |

| Occupation | physiologist, neurologist, naturalist |

| Years active | 1839–1879 |

| Title |

|

| Religion | Unitarian[1] |

| Spouse(s) | Louisa Powell (1840–1885) |

| Children | Five sons (see family information) |

| Parent(s) |

Dr Lant Carpenter, Anna Carpenter née Penn |

| Relatives |

Philip Pearsall Carpenter (brother)) Russell Lant Carpenter (brother) Mary Carpenter (sister) |

| Awards |

Royal Medal (1861) Lyell Medal (1883) |

| Signature | |

|

| |

William Benjamin Carpenter CB FRS (29 October 1813 – 19 November 1885)[1][2] was an English physician, invertebrate zoologist and physiologist. He was instrumental in the early stages of the unified University of London.

Life

Carpenter was born on 29 Oct 1813 in Exeter, the eldest son of Dr Lant Carpenter and his wife, Anna Carpenter (née Penn). His father was an important Unitarian preacher who influenced a "rising generation of Unitarian intellectuals, including James Martineau and the Westminster Review's John Bowring."[3] From his father, Carpenter inherited a belief in the essential lawfulness of the creation: this meant that natural causes were the explanation of the world as we find it. William embraced this "naturalistic cosmogeny" as his starting point.[3]

Carpenter was apprenticed to the eye surgeon John Bishop Estlin, who was also the son of a Unitarian minister, and accompanied him to the West Indies in 1833. He attended medical classes at University College London (1834–35), and then went to the University of Edinburgh (1835–39), where he received his MD in 1839.[3] Later, in 1861, he also received an LL.D. from the University of Edinburgh.[2]

On his resignation in 1879, Carpenter was appointed CB in recognition of his services to education. He died on 19 Nov 1885 in London, from burn injuries occasioned by the accidental upsetting of the fire heating a vapour bath he was taking. He was buried in Highgate Cemetery. [2][3]

Career

His graduation thesis on the nervous system of invertebrates[4] won a gold medal, and led to his first books.[5][6] His work in comparative neurology was recognised in 1844 by his election as a Fellow of the Royal Society. His appointment as Fullerian Professor of Physiology at the Royal Institution in 1845 enabled him to exhibit his powers as a teacher and lecturer. His gift of ready speech and luminous interpretation placing him in the front rank of exponents, at a time when the popularisation of science was in its infancy.[7]

He worked hard as investigator, author, editor, demonstrator and lecturer throughout his life; but it was his researches in marine zoology, notably in the "lower" organisms, as Foraminifera and Crinoids, that were most valuable.[8] These researches gave an impetus to deep-sea exploration, an outcome of which was in 1868 the oceanographic survey with HMS Lightning and later the more famous Challenger Expedition. He took a keen and laborious interest in the evidence adduced by Canadian geologists as to the organic nature of the so-called Eozoon canadense, discovered in the Laurentian strata, also called the North American craton, and at the time of his death had nearly finished a monograph on the subject, defending the now discredited theory of its animal origin. He was an adept in the use of the microscope, and his popular treatise on it stimulated many to explore this new aid.[9] He was president of the Quekett Microscopical Club from 1883–85. He was awarded the Royal Medal in 1861.[7]

Carpenter's most famous work is the Use and Abuse of Alcoholic Liquors in Health and Disease By William B. Carpenter, MD. F.R.S, F.G.S . Originally written as an Essay “ From the fifteen MS. Essays on the Use and Abuse of Alcoholic Liquors, transmitted to us by Messrs. Beggs and Gilpin for adjudication , they unanimously selected this one as the best and accordingly adjudicated to its author the Prize of One Hundred Guineas.” Awarded London Dec. 6th 1849. The first printing first edition was published in London by Charles Gilpin, 5 Bishopsgate Street Without; John Churchill, Princes Street, Soho; March 1850 . [ref. title page and preface from 1st edition 1st printing, private collection ] It was one of the first temperance books (Washingtonian Movement) to promote the fact that alcoholism is a disease.[7]

In 1856 Carpenter became Registrar of the University of London, and held the office for twenty-three years. Carpenter gave qualified support to Darwin but he had reservations as to the application of evolution to man's intellectual and spiritual nature.[7][10]

Adaptive unconscious

Carpenter is considered as one of the founders of the modern theory of the adaptive unconscious. Together with William Hamilton and Thomas Laycock they provided the foundations on which adaptive unconscious is based today. They observed that the human perceptual system almost completely operates outside of conscious awareness. These same observations have been made by Hermann Helmholtz. Because these views were in conflict with the theories of Descartes, they were largely neglected, until the cognitive revolution of the 1950s. in 1874 Carpenter noticed that the more he studied the mechanism of thought, the more clear it became that it operates largely outside awareness. He noticed that the unconscious prejudices can be stronger than conscious thought and that they are more dangerous since they happen outside of conscious.[7]

He also noticed that emotional reactions can occur outside of conscious until attention is drawn to them:

- "Our feelings towards persons and objects may undergo most important changes, without our being in the least degree aware, until we have our attention directed to our own mental state, of the alteration which has taken place in them." [11]

He also asserted both the freedom of the will and the existence of the Ego.[7] See also Sigmund Freud, William James, Unconscious mind.

Psychical research

Carpenter was a critic of claims of paranormal phenomena, psychical research and Spiritualism which he wrote were "epidemic delusions". His was the author of the book Mesmerism, Spiritualism, Etc: Historically and Scientifically Considered (1877) which is seen as an early text on anomalistic psychology. According to Carpenter, Spiritualist practices could be explained by psychological factors such as hypnotism and suggestion.[12] He wrote that Spiritualism could be compared to a form of insanity as its defenders were irrational about their beliefs.[13]

Family information

Carpenter married Louisa Powell in 1840 in Bristol. Louisa was born about 1815/1820 in England; she died in 1885.[14]

Their marriage had the following issue:

- Philip Herbert Carpenter (1852–1891). A master at Eton College, he was a zoologist who assisted his father and wrote extensively on fossils.[15]

- William Lant Carpenter was born in 1841 in Bristol, Somerset, England. William married Annie Viret in 1868 in Bristol, England. Annie was born in 1841 in Middlesex, England.

- Joseph Estlin Carpenter was born 5 October 1844 in Bristol and died 2 June 1927. He was a Unitarian and theologian.[16][17]

- Unknown male Carpenter was born about 1842/1855 in Bristol.

Works

| Wikisource has original works written by or about: William Benjamin Carpenter |

- Carpenter, William Benjamin (1874). Principles of Mental Physiology. H.S. King and Co (facsimile by Thoemmes Press 1998. ISBN 1-85506-662-9; reissued by Cambridge University Press 2009. ISBN 978-1-108-00528-9).

- Carpenter, William Benjamin; Carpenter, J. Estlin (1888). Nature and man: essays scientific and philosophical. London: Kegan Paul & Trench. A posthumous collection of his writings in periodicals.

- Carpenter, William Benjamin (1887). Mesmerism, Spiritualism, Etc: Historically and Scientifically Considered. New York: D. Appleton and Company.

- Carpenter, William Benjamin (1853). Condie, David Francis, ed. On the use and abuse of alcoholic liquors, in health and disease. Philadelphia: Blanchard & Lea.

- Carpenter, William Benjamin (12 March 1852). "On the influence of suggestion in modifying and directing muscular movement, independently of volition". Proceedings of the Royal Institution of Great Britain. The Royal Institution: 147–153.

- Carpenter, William Benjamin (1842 [First Edition]; 1843 [First American Edition]). Principles of Human Physiology. Philadelphia: Lea and Blanchard. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - Carpenter, William B. (1848). Animal Physiology (2nd ed.). London: Wm. S. Orr and Co. p. 579. The first edition was 1843, dedicated to Sir James Clark.

See also

Records of William Benjamin Carpenter at the University of Edinburgh via NAHSTE.[18]

- Mary Carpenter, his sister

- Phillip Pearsall Carpenter, his brother

- Dr Lant Carpenter, his father

- European and American voyages of scientific exploration

References

- 1 2 Smith, Roger (September 2004). "Carpenter, William Benjamin (1813–1885)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, online edition. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/4742. Retrieved 24 June 2010.

- 1 2 3 "Sketch of W. B. Carpenter". The Popular Science Monthly. 28: 538–544. February 1886. ISSN 0161-7370.

- 1 2 3 4 Desmond, Adrian (1989). "Chapter 5: Accommodation and Domestication: Dealing with Geoffroy's Anatomy – W. B. Carpenter and Lawful Morphology". The Politics of Evolution: Morphology, Medicine, and Reform in Radical London. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 210. ISBN 0-226-14346-5.

- ↑ Carpenter WB (1839). The Physiological Inferences to be deduced from the Structure of the Nervous System of Invertebrated Animals. Edinburgh: The University of Edinburgh.

- ↑ Carpenter WB (1839). Principles of General and Comparative Physiology. London: Churchill.

- ↑ Carpenter WB (1859) [First published 1843]. Animal Physiology. London: H. G. Bohn.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Thomas, KB (2008). Gillispie CC, ed. Complete Dictionary of Scientific Biography. 3. Detroit: Charles Scribner's Sons. pp. 87–89, (005006490) R920.

- ↑ Carpenter W.B. 1845. Zoology: being a systematic account of the general structure, habits, instincts and uses of the principal families of the animal kingdom. 2 vols: Orr, London.

- ↑ Carpenter W.B. 1856. The microscope and its revelations.

- ↑ Desmond A. 1989. The politics of evolution p419. Chicago.

- ↑ Carpenter W.B. 1875. Principles of mental physiology. 2nd ed. King, London. p24-8, 516–7, 519–20, 539–41.

- ↑ Janet Oppenheim. (1988). The Other World: Spiritualism and Psychical Research in England, 1850–1914. Cambridge University Press.

- ↑ Alex Owen. (2004). The Darkened Room: Women, Power, and Spiritualism in Late Victorian England. The University of Chicago Press.

- ↑ Carpenters' Encyclopedia of Carpenters 2009, data DVD. Genealogy and family history of the Carpenter and related families. Subject is RIN 25570.

- ↑ Bonney TG; rev. Quirke VM (2004). "Carpenter, Philip Herbert (1852–1891)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, online edition. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/4735. Retrieved 24 June 2010.

- ↑ Long AJ (September 2004). "Carpenter, (Joseph) Estlin (1844–1927)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, online edition. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/32303. Retrieved 24 June 2010.

- ↑ Temporarily out of service. Archivegrid.org. Retrieved on 18 September 2011.

- ↑ "Carpenter | William Benjamin | 1813–1885 | naturalist botanist" (TML). NAHSTE. The University of Edinburgh. Retrieved 24 June 2010.

- Student Records (1839)

- Letter to Sir Charles Lyell from William Benjamin Carpenter (1850)

- Correspondence to Sir Archibald Geikie: Thomas Lauder Brunton to William Sweetland Dallas (1857–1913)

- Letter to Sir Charles Lyell from William Benjamin Carpenter (1863)

- Letter to Sir Charles Lyell from William Benjamin Carpenter (1864)

- Letter to Sir Charles Lyell from William Benjamin Carpenter (1865)

- Letter to Sir Charles Lyell from William Benjamin Carpenter (1865)

- Letter to Sir Charles Lyell from William Benjamin Carpenter (1866)

External links

- "Archival material relating to William Benjamin Carpenter". UK National Archives.

- Fullerian Professorships

- Works of William Benjamin Carpenter at the Biodiversity Heritage Library

| Academic offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Thomas Rymer Jones |

Fullerian Professor of Physiology 1844–1848 |

Succeeded by William Withey Gull |