Vishvarupa

| Vishvarupa | |

|---|---|

|

Arjuna bows to Vishvarupa | |

| Devanagari | विश्वरूपा |

| Sanskrit transliteration | viśvarūpa |

| Affiliation | Cosmic form of Vishnu/Krishna |

Vishvarupa ("Universal form", "Omni-form"), also known popularly as Vishvarupa Darshan, Vishwaroopa and Virata rupa, is an iconographical form and theophany of the Hindu god Vishnu or his avatar Krishna. The direct revelation by the One without a Second, Master-Lord of the Universe. Though there are multiple Vishvarupa theophanies, the most celebrated is in the Bhagavad Gita, "the Song of God", given by Krishna in the epic Mahabharata, which was told to Pandava Prince Arjuna on the battlefield of Kurukshetra in the war in the Mahabharata between the Pandavas and Kauravas. Vishvarupa is considered the supreme form of Vishnu, where the whole universe is described as contained in him and this show that actual god is centralised within different gods and god is one.

Literary descriptions

In the climactic war in the Mahabharata, the Pandava prince Arjuna and his brothers fight against their cousins, the Kauravas with Krishna as his charioteer. Faced with moral dilemma that whether or not to fight against and kill his own or for dharma (duty), Krishna discourses him about life and death and reveals his Vishvarupa as a theophany. In chapters 10 and 11, Krishna reveals himself as the Supreme Being and finally displays his Vishvarupa to Arjuna. Arjuna experiences the vision of the Vishvarupa with divine vision endowed to him by Krishna. Vishvarupa's appearance is described by Arjuna, as he witnesses it.[1][2]

Vishvarupa has innumerable forms, eyes, faces, mouths and arms. All creatures of the universe are part of him. He is the infinite universe, without a beginning or an end. He contains peaceful as well as wrathful forms. Unable to bear the scale of the sight and gripped with fear, Arjuna requests Krishna to return to his four-armed Vishnu form, which he can bear to see.[1][2][3] Fully encouraged by the teachings and darshan of Krishna in his full form, Arjuna continued the Mahabharata War.[2][4]

There are two more descriptions in the Mahabharata, where Krishna or Vishnu-Narayana offers the theophany similar to the Vishvarupa in the Bhagavad Gita. When negotiations between Pandavas and Kauravas break down with Krishna as the Pandava messenger, Krishna declares that he is more than human and displays his cosmic form to the Kaurava leader Duryodhana and his assembly. Vishvarupa-Krishna appears with many arms and holds many weapons and attributes traditionally associated with Vishnu like the conch, the Sudarshana chakra, the gada (mace), his bow, his sword Nandaka. The inside of his body is described. Various deities (including Vasus, Rudras, Adityas, Dikapalas), sages and tribes (especially those opposing the Kauravas, including the Pandavas) are seen in his body. This form is described as terrible and only people blessed with divine vision could withstand the sight.[5]

The other theophany of Vishnu (Narayana) is revealed to the divine sage Narada. The theophany is called Vishvamurti. The god has a thousand eyes, a hundred heads, a thousand feet, a thousand bellies, a thousand arms and several mouths. He holds weapons as well as attributes of an ascetic like sacrificial fire, a staff, a kamandalu (water pot).[6]

Another theophany in the Mahabharata is of a Vaishnava (related to Vishnu or Krishna) form. It misses the multiple body parts of Vishvarupa, but conveys the vastness and cosmic nature of the deity. His head covers the sky. His two feet cover all ground. His two arms encompass the horizontal space. His belly occupies the reattaining space in the universe.[6]

Vishvarupa is also used in the context of Vishnu's "dwarf" avatar, Vamana in the Harivamsa. Vamana, arrives at the asura king Bali's sacrifice as a dwarf Brahmin boy and asks for three steps of land as donation. Where the promise is given, Vamana transforms into his Vishvarupa, containing various deities in his body. The sun and the moon are his eyes. The earth his feet and heaven is his head. Various deities; celestial beings like Vasus, Maruts, Ashvins, Yakshas, Gandharvas, Apsaras; Vedic scriptures and sacrifices are contained in his body. With his two strides, he gains heaven and earth and placing the third on Bali's head, who accepts his mastership. Bali is then pushed to the realm of Patala (underworld).[7]

Vishvarupa is also interpreted as “the story of evolution,” as the individual evolves in this world doing more and more with time. The Vishvarupa Darshan is a cosmic representation of gods and goddesses, sages and asuras, good and the bad as we perceive in our own particular perspective of existence in this world.[8]

Development

The name Vishvarupa (viśva "whole", "universe" and rūpa "form", lit. "All-formed" or "Omniform") first appears as a name of Trisiras, the three-headed son of Tvastr, the Vedic creator-god who grants form to all beings.[9] In the Rig Veda, he is described as to generate many forms and contain several forms in his womb.[10] The epithet Vishvarupa is also used for other deities like Soma (Rig Veda), Prajapati (Atharva Veda), Rudra (Upanishad) and the abstract Brahman (Maitrayaniya Upanishad).[11] The Atharva Veda uses the word with a various connotation. A bride is blessed with be Vishvarupa (all-formed) with glory and offspring.[10]

Then, Vishvarupa is revealed in the Bhagavad Gita (2nd century BCE) and then the Puranas (1000 BCE - 500 CE) in connection to Vishnu-Krishna, however these literary sources do not detail the iconography of Vishvarupa.[12] The Bhagavad Gita may be inspired by the description of Purusha as thousand-headed, thousand-eyed and thousand-footed or a cosmic Vishvakarma ("creator of the universe").[13]

Vishvarupa is mentioned as Vishnu's avatar in Pañcaratra texts like the Satvata Samhita and the Ahirbudhnya Samhita (which mention 39 avatars) as well as the Vishnudharmottara Purana, that mentions 14 avatars.[14][15]

Iconography

The literary sources mentions that Vishvarupa has "multiple" or "thousand/hundred" (numeric equivalent of conveying infinite in literary sources) heads and arms, but do not give a specific number of body parts that can be depicted. Early Gupta and post-Gupta sculptors were faced with difficulty of portraying infiniteness and multiple body parts in a feasible way.[16] Arjuna's description of Vishvarupa gave iconographers two options: Vishvarupa as a multi-headed and multi-armed god or all components of the universe displayed in the body of the deity.[17] Early Vishvarupa chose the former, while Buddhist images of a Cosmic Buddha were displayed in the latter format. An icon, discovered in Parel, Mumbai dated to c. 600, has seven figures all appearing interlinked to each other. Though the icon mirrors the Vishvarupa of Vishnu, it is actually a rare image of the Vishvarupa of Shiva.[17]

Vishvarupa becomes crystallized as an icon in the early Vishnu cult by the time of Guptas (6th century CE). The first known image of Vishvarupa is a Gupta stone image from the Mathura school, found in Bhankari, Angarh district, dated c. 430-60 CE. The Gupta sculptor is inspired by the Bhagavad Gita description. Visvarupa has three heads: a human (centre), a lion (the head of Narasimha, the man-lion avatar of Vishnu) and a boar (the head of Varaha, the boar avatar of Vishnu) and four arms. Multiple beings and Vishnu's various avatars emerge from the main figure, accompanying half of the 38 cm (high) X 47 cm (wide) stela. Another early image (70 cm high) is present in the Changu Narayan temple, Nepal, dated 5th-6th century. The central image is ten-headed and ten-armed and is surrounded by the three regions of Hindu cosmology, Svarga (heavenly realms, upper portion of the stone relief), Prithvi (the earth, the middle) and Patala (the underworld, the bottom) and corresponding beings gods, humans and animals and nagas and spirits respectively. The figures on his right are demonic while on the left are divine, representing the dichotomy of his form. A similar early image is also found at and the Varaha Temple, Deogarh, Uttar Pradesh.[18] A 5th century Garhwa image shows Vishvarupa with six arms and three visible heads: a horse (centre, Hayagriva-avatar of Vishnu), a lion and a boar. Possibly a fourth head existed which popped up from the horse head. An aureole of human head surround the central heads. Flames emitting from the figure, illustrating its blazing nature as described by Arjuna.[19] Three Vishvarupa icons from Shamalaji, Gujarat dated sixth century have three visible animal heads and eight arms, with a band of beings emanating from the upper part of the deity forming an aureole. Unlike other icons which are in standing position, the Shamalaji icons are in a crouching position, as though giving birth and is similar to icons of birth-giving mother goddesses in posture. The posture may convey the idea that he is giving birth to the beings radiating from him, though none of them are near his lower area.[20]

The Vishnudharmottara Purana prescribes that Vishvarupa have four arms and should have as many as arms that can be possibly depicted.[21] A 12th-century sculpture of Vishvarupa from Rajasthan shows a fourteen-armed Vishnu riding his mount Garuda. The image has three visible human heads, unlike the early sculptures which include animal ones.[22] Some iconographic treatises prescribe a fourth demonic head at the back, however this is generally not depicted in iconography.[22]

Another iconography prescribes that Vishvarupa be depicted with four faces: male (front, east), lion/Narasimha (south), boar/Varaha (north) and woman (back/west). He should ride his Garuda. He has twenty arms: a left and right arm outstretched in pataka-hasta and another pair in yoga-mudra pose. The other fourteen hold hala (plough), shankha (conch), vajra (thunderbolt), ankusha (goad), arrow, sudarshana chakra, a lime fruit, danda (staff), pasha (noose), gada (mace), sword, lotus, horn, musala (pestle), akshamala (rosary). A hand is held in varada mudra (boon-giving gesture).[23]

The artistic imagination of Hindu artists of Nepal has created iconic Vishvarupa images, expressing "sacred terror", as expressed by Arjuna. Vishvarupa has twenty heads arranged in tiers. They include Vishnu's animal avatars Matsya (fish), Kurma (tortoise), boar (Varaha), lion (Narasimha) as well as heads of vahanas (mounts) of Hindu deities: elephant (of Indra), eagle (Garuda of Vishnu) and bull (of Shiva). Among the human heads, Vishnu’s avatars as Parashurama, Rama, Krishna and Buddha. His two main hands hold the sun and the moon. He has ten visible legs and three concentric rings of hands accounting to 58. Other artistic representations of Vishvarupa in Nepal have varying number of heads, hands and legs and some have even attributes of Mahakala and Bhairava, such as flaying knife and skull bowl. Other attributes shown are arrows, bows, bell, vajra, sword with shield, umbrella and canopy. Another terrifying feature is a face on the belly that gorges a human being.[24]

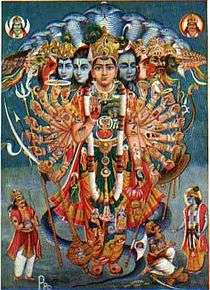

In modern calendar art, Vishvarupa is depicted having many heads, each a different aspect of the divine. Some of the heads breathe fire indicating destructive aspects of God. Many deities are seen on his various body parts. His many hands hold various weapons. Often Arjuna features in this scene bowing to Vishvarupa.[25]

References

- 1 2 Howard pp. 58-60

- 1 2 3 Sharma, Chakravarthi; Sharma, Rajani; Sharma, Mrs. Rajani (2004). Self Offerings. pp. 18–19. ISBN 9781418475024. Retrieved 8 December 2012.

- ↑ Srinivasan pp. 20-1

- ↑ Competition, Sura College of; Padmanabhan, M.; Shankar, Meera Ravi (2004). Tales of Krishna from Mahabharata. Sura Books. p. 88. ISBN 9788174784179. Retrieved 8 December 2012.

- ↑ Srinivasan p. 135

- 1 2 Srinivasan p. 136

- ↑ Deborah A. Soifer (1991). The Myths of Narasiṁha and Vāmana: Two Avatars in Cosmological Perspective. SUNY Press. pp. 135–8. ISBN 978-0-7914-0800-1. Retrieved 9 December 2012.

- ↑ Carl Becker; J Becker Carl J Becker (8 April 2010). A Modern Theory of Evolution. iUniverse. pp. 330–. ISBN 978-1-4502-2449-9. Retrieved 8 December 2012.

- ↑ Howard p. 57

- 1 2 Srinivasan p. 6

- ↑ Srinivasan pp. 27, 37, 131

- ↑ Howard p. 60

- ↑ Srinivasan pp. 20-1, 134

- ↑ Roshen Dalal (5 October 2011). Hinduism: An Alphabetical Guide. Penguin Books India. p. 459. ISBN 978-0-14-341421-6.

- ↑ Manohar Laxman Varadpande (2009). Mythology of Vishnu & His Incarnations. Gyan Publishing House. p. 45. ISBN 978-81-212-1016-4. Retrieved 9 December 2012.

- ↑ Srinivasan p. 137

- 1 2 Howard p. 63

- ↑ Howard pp. 60-1

- ↑ Srinivasan p. 138

- ↑ Srinivasan pp. 138-40

- ↑ Srinivasan p. 140

- 1 2 Los Angeles County Museum Of Art; MR Pratapaditya Pal (1 February 1989). Indian Sculpture (700-1800): A Catalog of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art Collection. University of California Press. p. 132. ISBN 978-0-520-06477-5. Retrieved 9 December 2012.

- ↑ Rao, T.A. Gopinatha (1916). Elements of Hindu Iconography. 1: Part I. Madras: Law Printing House. p. 258.

- ↑ Linrothe, h Robert N; Watt, Jeff; Rhie, Marylin M. (2004). Demonic Divine: Himalayan Art and Beyond. Serindia Publications, Inc. pp. 242, 297. ISBN 9781932476088. Retrieved 9 December 2012.

- ↑ Devdutt Pattanaik (1 November 2009). 7 Secrets of Hindu Calendar Art. Westland Ltd./HOV Services. ISBN 978-81-89975-67-8. Retrieved 10 December 2012.

- Howard, Angela Falco (1986). "Possible Brahmanic Influences in the cosmological Buddha". The Imagery of the Cosmological Buddha. Brill Archive. ISBN 978-90-04-07612-9. Retrieved 8 December 2012.

- Srinivasan, Doris (1997). Many Heads, Arms, and Eyes: Origin, Meaning, and Form of Multiplicity in Indian Art. BRILL. ISBN 978-90-04-10758-8. Retrieved 8 December 2012.