Virginia Constitutional Convention of 1868

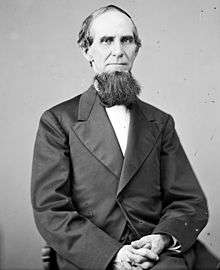

1868 Presiding officer

| History of Virginia |

|---|

|

|

|

The Virginia Constitutional Convention of 1868, was an assembly of delegates elected by the voters to establish the fundamental law of Virginia following the American Civil War and the Fourteenth Amendment. The Convention set the stage for enfranchising freedmen, Virginia's readmission to Congress and an end to Congressional Reconstruction.

Background and composition

After 1866, according to the Radical Reconstruction Acts of Congress, a rebelling state which had vacated its delegation in the U.S. Congress was required to constitutionally incorporate the 14th Amendment before it was allowed to participate again. That Amendment guarantees that all persons born in the United States are both citizens of the United States and citizens of their state. States were forbidden to either abridge the privileges of its citizens or to deny equal protection of their laws to any citizen any longer. The Radical Congressional Reconstruction legislation required the suffrage for black men.[1]

During Reconstruction, U.S. General John Schofield was administering Virginia as Military District One. By the time he called a new state constitutional convention for 1868, three distinct parties had coalesced in Virginia. Radical Republicans including most ex-slave freedmen, organized to advocate full political and social equality for blacks, but they wanted to exclude ex-Confederates from political participation either in government or at the ballot box. Moderate Unionists including many pre-war Whigs, sought political equality for blacks, but believed that ex-Confederates had to be included in the political community because of their majority in the white population. Conservatives wanted to ensure white control of the state without Radical influence on issues such as public education.[2] In the elections for the Constitutional Convention, Radical Republican superior organization gained a surprise triumph over both Moderates and Conservatives, resulting in a majority of Convention delegates. The statewide majority of white ex-Confederates immediately organized Virginia’s Conservative Party which incorporated the moderate former Unionists to seek white-only control of the state.[3]

The Convention’s 104 delegates included 68 Republicans with 24 blacks in their ranks, 21 native Virginia born whites and 23 whites from out of state. The remaining 36 Conservatives were mostly wealthy ex-Confederates.[4]

Meeting and debate

The Convention met from December 3, 1867 - April 17, 1868, at Richmond in the Capitol Building, and elected John Curtiss Underwood its presiding officer, a Republican Federal Judge who had been living in Virginia since the 1840s and famous for expropriating Confederate plantation lands.[5] its presiding officer. A convention of enfranchised Unionists, freedmen and ex-Confederates was dominated by Radical Republicans. The Convention proposed two "obnoxious clauses" meant to restrict suffrage among ex-Confederates. Negotiations with President Grant resulted in separating the two more controversial proposals, and the remaining Constitution was ratified by referendum. It provided for the vote for African-Americans and public education.[6]

|

Virginia’s Constitution has begun with its Declaration of Rights since 1776. A radical proposed inclusive language to read, “All mankind, irrespective of race or color, are by nature equally free and independent and have certain inherent rights.” But black floor leader Thomas Bayne of Norfolk had promised his voters that the Constitution would not have “the word black or the word white anywhere in it”, that their children reading it in fifteen years would “not see slavery, even as a shadow, remaining in it…” and the measure was defeated by a coalition of black Republicans and Conservatives. Conservatives also objected to the Radical assertion that the right to vote was a natural right, because the saw it as a social privilege meant to be restricted to the few. That provision was also defeated.[7]

The Convention concerned itself with federal-state relations, with the Convention’s Committee on the Preamble and Bill of Rights initially stating that, "“the General Government of the United States is paramount to that of an individual state, except as to rights guaranteed to each State by the Constitution of the United States.” But Jacob N. Liggett of Rockingham voiced the ex-Confederate doctrine that “the Federal Government is the creature of the acts of the States.” Christopher Y. Thomas of Henry County proposed a compromise, to simply assert Article VI. of the U.S. Constitution for Virginia’s Bill of Rights, Section 2, that “the Constitution of the United States, and the laws of Congress passed in pursuance thereof, constitute the supreme law of the land, to which paramount allegiance and obedience are due from every citizen…” That was not enough for the Radical majority, Linus M. Nickerson of Fairfax who had served in a New York infantry regiment successfully added that, “this State shall ever remain a member of the United States of America…and that all attempts from whatever source, or upon whatever pretext, to dissolve said Union… are unauthorized, and ought to be resisted with the whole power of the State.”[8]

While the Convention provided for public education, the Radicals failed in their efforts to secure a Constitutional mandate for racial integration of the schools. Black delegates at the Convention were divided nearly equally between supporting mandatory integration and leaving the issue for the General Assembly. Some delegates believed that allowing for segregated schools would end the objections to public schooling which had been resisted in the General Assembly since Jefferson's proposals in the 1700s.[9]

However, the Radicals in Convention, against the protests of General Schofield, were able to martial an uncompromised majority in their desire to disenfranchise the white ex-Confederate majority in the state. Instead of limiting voter restrictions for former U.S. officeholders who had supported rebellion, they sought to guarantee a future government of Union men only. The Convention wrote two “obnoxious clauses” as they were widely known, that went beyond federal requirements to deny the vote to any office holder in rebel government and an “iron--clad oath” testifying that a prospective voter had never “voluntarily borne arms against the United States.”[10]

Outcomes

Following the Convention, in November 1868 former Union General Ulysses S. Grant was elected, though Virginia, Mississippi and Texas did not participate as "unreconstructed" states. General Schofield successfully negotiated with President Grant to propose the referendum on the Radical “Underwood” Constitution, but separating its two disenfranchisement “obnoxious clauses”, allowing voters to decide on them apart from the Constitution.[11] While the referendum on the main body of the Constitution was overwhelmingly approved, the two “obnoxious clauses” were defeated by a narrower margin.[12]

In the subsequent elections, the moderate Republican Gilbert Carlton Walker won the governorship. The General Assembly elections returned a two-thirds veto proof Conservative majority, but Virginia elected twenty-nine black delegates and state senators.[13] Both the 14th Amendment and the 15th Amendment enfranchising African Americans were ratified by the General Assembly, and on January 26, 1870, President Grant signed the legislation seating Virginia’s delegation in Congress.[14]

See also

References

- ↑ Wallenstein 2007, p. 221-222

- ↑ Wallenstein 2007, p. 221

- ↑ Lowe 1991, p. 129

- ↑ Heinemann 2007, p. 247-248

- ↑ Heinemann 2007, p. 247-248

- ↑ Wallenstein 2007, p. 221-222

- ↑ Dinan 2006, p. 13

- ↑ Dinan 2006, p. 14

- ↑ Lowe 1991, p. 138

- ↑ Dabney (1971) 1989, p. 368

- ↑ Dabney (1971) 1989, p. 368

- ↑ Wallenstein 2007, p. 223

- ↑ Wallenstein 2007, p. 223

- ↑ Heinemann 2007, p. 250

Bibliography

- Dabney, Virginius (1989). Virginia: the New Dominion, a history from 1607 to the present. University of Virginia Press. ISBN 9780813910154.

- Dinan, John (2014). The Virginia State Constitution: a reference guide. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199355747.

- Heinemann, Ronald L. (2008). Old Dominion, New Commonwealth: a history of Virginia, 1607-2007. University of Virginia Press. ISBN 978-0-8139-2769-5.

- Lowe, Richard G. (1991). Republicans and Reconstruction in Virginia, 1856-70. University of Virginia Press. ISBN 978-0-8139-1306-3.

- Wallenstein, Peter (2007). Cradle of America: a history of Virginia. University Press of Kansas. ISBN 978-0-7006-1994-8.

External links

- The Debates and proceedings of the Constitutional convention of the state of Virginia, assembled at the city of Richmond, tuesday, December 3, 1867 New Nation, Richmond 1868 on line at Hathi Trust Digital Library