Diel vertical migration

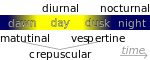

Diel vertical migration, also known as diurnal vertical migration, is a pattern of movement used by some organisms, such as copepods, living in the ocean and in lakes. The migration occurs when organisms move up to the epipelagic zone at night and return to the mesopelagic zone of the oceans or to the hypolimnion zone of lakes during the day. The word diel comes from the Latin dies day, and means a 24-hour period. It is the greatest migration in the world in terms of biomass.[1]

Discovery

During World War II the U.S. Navy was taking sonar readings of the ocean when they discovered the deep scattering layer (DSL). The DSL was caused by large groupings of organisms that scattered the sonar to create a false or second bottom. The false bottom was shallower during the night and deeper during the day; this was the first recording of diel vertical migration.

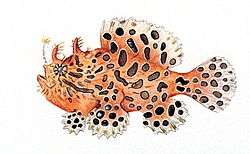

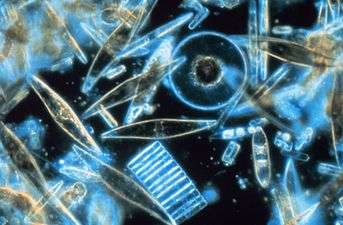

Once scientists started to do more research on what was causing the DSL, it was discovered that a large range of organisms were vertically migrating. Most types of plankton and some types of nekton have exhibited some type of vertical migration, although it is not always diel. These migrations may have substantial effects on mesopredators and apex predators by modulating the concentration and accessibility of their prey (e.g., impacts on the foraging behavior of pinnipeds[2]).

Types and stimuli of vertical migration

There are two different factors that are known to play a role in vertical migration, endogenous and exogenous. Endogenous factors originate from the organism itself; sex, age, biological rhythms, etc. Exogenous factors are environmental factors acting on the organism such as light, gravity, oxygen, temperature, predator-prey interactions, etc.

Endogenous factors

- Endogenous rhythm

- An experiment was done at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography which kept organisms in column tanks with light/dark cycles. A few days later the light was changed to a constant low light and the organisms still displayed diel vertical migration. Thus suggestions that some type of internal response was causing the migration.[3]

Exogenous factors[4]

- Light

- Organisms want to find an optimum light intensity (isolume). Whether it is no light or a large amount of light, an organism will travel to where it is most comfortable. Studies have shown that during a full moon organisms will not migrate up as far or during an eclipse they will start to migrate.

- Temperature

- Sometimes thermoclines can act as a barrier that an organism will not cross.

- Salinity

- In areas such as the Arctic melting ice causes a layer of freshwater which organisms cannot cross.

- Predator kairomones

- A predator might release a chemical cue which could cause its prey to vertically migrate away.[5]

Types of vertical migration

- Diel

- This is the most common form. Organisms migrate daily, usually up to shallow waters at night and deep waters during the day.

- Seasonal

- Organisms are found at different depths depending on what season it is.[6]

- Ontogenetic

- Organisms spend different stages of their life cycle at different depths.[7]

Reasons for vertical migration

There are many hypotheses as to why organisms would vertically migrate, and several may be valid at any given time.[8]

- Predator avoidance

- Light-dependent predation by fish is a common pressure that causes DVM behavior in zooplankton. A given body of water may be viewed as a risk gradient whereby the surface layers are riskier to reside in during the day than deep water, and as such promotes varied longevity among zooplankton that settle at different daytime depths.[9] Indeed, in many instances it is advantageous for zooplankton to migrate to deep waters during the day to avoid predation and come up to the surface at night to feed.

- Metabolic advantages

- By feeding in the warm surface waters at night and residing in the cooler deep waters during the day they can conserve energy. Alternatively, organisms feeding on the bottom in cold water during the day may migrate to surface waters at night in order to digest their meal at warmer temperatures.

- Dispersal and transport

- Organisms can use deep and shallow currents to find food patches or to maintain a geographical location.

- Avoid UV damage

- The sunlight can penetrate into the water column. If an organism, especially something small like a microbe, is too close to the surface the UV can damage them. So they would want to avoid getting too close to the surface, especially during daylight.

Water transparency

A recent theory of DVM, termed the Transparency Regulator Hypothesis, argues that water transparency is the ultimate variable that determines the exogenous factor (or combination of factors) that causes DVM behavior in a given environment.[10] In less transparent waters, where fish are present and more food is available, fish tend to be the main driver of DVM. In more transparent bodies of water, where fish are less numerous and food quality improves in deeper waters, UV light can travel farther, thus functioning as the main driver of DVM in such cases.[11]

Importance for the biological pump

The biological pump is the conversion of CO2 and inorganic nutrients by plant photosynthesis into particulate organic matter in the euphotic zone and transference to the deeper ocean.[12] This is a major process in the ocean and without vertical migration it wouldn’t be nearly as efficient. The deep ocean gets most of its nutrients from the higher water column when they sink down in the form of marine snow. This is made up of dead or dying animals and microbes, fecal matter, sand and other inorganic material.

Organisms migrate up to feed at night so when they migrate back to depth during the day they defecate large sinking fecal pellets.[12] Whilst some larger fecal pellets can sink quite fast, the speed that organisms move back to depth is still faster. At night organisms are in the top 100 metres of the water column, but during the day they move down to between 800–1000 meters. If organisms were to defecate at the surface it would take the fecal pellets days to reach the depth that they reach in a matter of hours. Therefore, by releasing fecal pellets at depth they have almost 1000 metres less to travel to get to the deep ocean. This is something known as active transport. The organisms are playing a more active role in moving organic matter down to depths. Because a large majority of the deep sea, especially marine microbes, depends on nutrients falling down, the quicker they can reach the ocean floor the better.

Zooplankton and salps play a large role in the active transport of fecal pellets. 15-50% of zooplankton biomass is estimated to migrate, accounting for the transport of 5-45% of particulate organic nitrogen to depth.[12] Salps are large gelatinous plankton that can vertically migrate 800 meters and eat large amounts of food at the surface. They have a very long gut retention time, so fecal pellets usually are released at maximum depth. Salps are also known for having some of the largest fecal pellets. Because of this they have a very fast sinking rate, small detritus particles are known to aggregate on them. This makes them sink that much faster. So while currently there is still much research being done on why organisms vertically migrate, it is clear that vertical migration plays a large role in the active transport of dissolved organic matter to depth.[13]

See also

References

- ↑ "Diel Vertical Migration (DVM)". Retrieved 5 April 2012.

- ↑ Horning, M.; Trillmich, F. (1999). "Lunar cycles in diel prey migrations exert a stronger effect on the diving of juveniles than adult Galapagos fur seals". Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 266: 1127–1132. doi:10.1098/rspb.1999.0753.

- ↑ Enright, J.T.; W.M. Hammer (1967). "Vertical Diurnal Migration and Endogenous Rhythmicity". Science. 157 (3791): 937–941. doi:10.1126/science.157.3791.937. JSTOR 1722121. PMID 17792830.

- ↑ Richards, Shane; Hugh Possingham; John Noye (1996). "Diel vertical migration: modeling light-mediated mechanisms" (PDF). Journal of Plankton Research. 18 (12): 2199–2222. doi:10.1093/plankt/18.12.2199.

- ↑ von Elert, Eric; Georg Pohnert (2000). "Diel Predator specificity of kairomones in diel vertical migration of Daphnia: a chemical approach". OIKOS. 88 (1): 119–128. doi:10.1034/j.1600-0706.2000.880114.x. ISSN 0030-1299.

- ↑ Visser, Andre; Sigrun Jonasdottir (1999). "Lipids, buoyancy and the seasonal vertical migration of Calanus finmarchicus". Fisheries Oceanography. 8: 100–106. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2419.1999.00001.x.

- ↑ Kobari, Toru; Tsutomu Ikeda (2001). "Octogenetic vertical migration and life cycle of Neocalanus plumchrus (Crustacea:Copepoda) in the Oyashio region, with notes on regional variations in body size" (PDF). Journal of Plankton Research. 23 (3): 287–302. doi:10.1093/plankt/23.3.287.

- ↑ Kerfoot, WC (1985). "Adaptive value of vertical migration: Comments on the predation hypothesis and some alternatives". Contributions in Marine Science. 27: 91–113.

- ↑ Dawidowicz, Piotr; Prędki, Piotr; Pietrzak, Barbara (2012-11-23). "Depth-selection behavior and longevity in Daphnia: an evolutionary test for the predation-avoidance hypothesis". Hydrobiologia. 715 (1): 87–91. doi:10.1007/s10750-012-1393-5. ISSN 0018-8158.

- ↑ "Web of Science [v.5.20] - Web of Science Core Collection Full Record". apps.webofknowledge.com. Retrieved 2015-11-14.

- ↑ Tiberti, Rocco; Iacobuzio, Rocco (2012-12-09). "Does the fish presence influence the diurnal vertical distribution of zooplankton in high transparency lakes?". Hydrobiologia. 709 (1): 27–39. doi:10.1007/s10750-012-1405-5. ISSN 0018-8158.

- 1 2 3 Steinberg, Deborah; Sarah Goldthwait; Dennis Hansell (2002). "Zooplankton vertical migration and the active transport of dissolved organic and inorganic nitrogen in the Sargasso Sea". Deep-Sea Research Part I. 49 (8): 1445–1461. doi:10.1016/S0967-0637(02)00037-7. ISSN 0967-0637.

- ↑ Wiebe, P.H; L.P. Madin; L.R. Haury; G.R. Harbison; L.M. Philbin (1979). "Diel Vertical Migration by Salpa aspera and its potential for large-scale particulate organic matter transport to the deep-sea". Marine Biology. 53 (3): 249–255. doi:10.1007/BF00952433.