Ventana Wilderness

| Ventana Wilderness | |

|---|---|

|

IUCN category Ib (wilderness area) | |

| |

| Location | Los Padres National Forest, Monterey County, California, United States |

| Nearest city | Monterey, CA |

| Coordinates | 36°15′0″N 121°40′0″W / 36.25000°N 121.66667°WCoordinates: 36°15′0″N 121°40′0″W / 36.25000°N 121.66667°W |

| Area | 240,026 acres (971 km2) |

| Established | August 18, 1969 |

| Governing body | U.S. Forest Service / Bureau of Land Management |

The Ventana Wilderness of Los Padres National Forest is a federally designated wilderness area located in the Santa Lucia Mountains along the Central Coast of California. This wilderness was established in 1969 when the Ventana Wilderness Act redesignated the 55,800-acre (226 km2) Ventana Primitive Area as the Ventana Wilderness and added land, totalling 98,000-acre (400 km2). In 1978, the Endangered American Wilderness Act added 61,000 acres (250 km2), increasing the total wilderness area to about 159,000 acres (640 km2). The California Wilderness Act of 1984 added about 2,750 acres (11 km2). In 1992, the Los Padres Condor Range and River Protection Act created the approximately 14,500-acre (59 km2) Silver Peak Wilderness and added about 38,800 acres (157 km2) to the Ventana Wilderness.

The bill also designated the Big Sur River as a wild and scenic river. Most recently, the Big Sur Wilderness and Conservation Act of 2002 expanded the wilderness for the fifth time, adding nearly 35,000 acres (140 km2), increasing the total acreage of the wilderness to its present size of 240,026 acres (971 km2).[1]

Name origin

The Ventana Wilderness is named for the unique notch called "The Window" on a ridge near Ventana Double Cone. According to local legend, this notch was once a natural stone arch.[2]

History

Native America use

Three tribes of Native Americans—the Ohlone, Esselen, and Salinan—are believed to have been the first people to inhabit the area. The Ohlone, also known as the Costanoans, are believed to have lived in the region from San Francisco to Point Sur. The Esselen lived in the area between Point Sur south to Big Creek, and inland including the upper tributaries of the Carmel River and Arroyo Seco watersheds. The Salinan lived from Big Creek south to San Carpoforo Creek.[3] Archaeological evidence shows that the Esselen lived in Big Sur as early as 3500 BC, leading a nomadic, hunter-gatherer existence.[4][5]

The indigenous people lived near the coast in winter, where they harvested rich stocks of mussels, abalone and other sea life. In the summer and fall they moved inland to harvest acorns gathered from the Black Oak, Canyon Live Oak and Tanbark Oak, primarily on upper slopes in areas on the upper slopes of the steep canyons.[6]:270

Founding and additions

U.S. Forest Service Chief Forester R. Y. Stuart ordered the Monterey Ranger District to establish the Ventana Primitive Area. It originally consisted of 45,520 acres (184 km2) and was enlarged in 1937 to about 55,884 acres (22,615 ha). When the U.S. Congress passed the The Wilderness Act of 1964, the Ventana Primitive Area was formally designated as wilderness by law, rather than by a Forest Service regulation, which made the area's status subject to change at will. The Ventana Wilderness Area was formally established on August 18, 1969. The Ventana initially included 164,554 acres (666 km2) acres of primarily extremely rugged terrain within the Santa Lucia Mountains of the Monterey Ranger District.[7]

In 1978, the Endangered American Wilderness Act added 61,000 acres (250 km2), increasing the total wilderness area to about 159,000 acres (640 km2). The California Wilderness Act of 1984 added about 2,750 acres (11 km2). In 1992, the Los Padres Condor Range and River Protection Act created the approximately 14,500-acre (59 km2) Silver Peak Wilderness and added about 38,800 acres (157 km2) to the Ventana Wilderness. In 2002, the Big Sur Wilderness and Conservation Act added nearly 35,000 acres (140 km2), increasing the total acreage of the wilderness to its present size of 240,026 acres (971 km2).[1] A very small part, 736 acres (3 km2), on the eastern edge of the wilderness is managed by the Bureau of Land Management.[8]

Topography

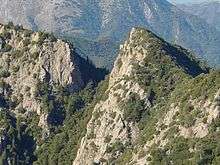

The topography of the Ventana Wilderness is characterized by steep-sided, sharp-crested ridges separating V-shaped youthful valleys. Most streams fall rapidly through narrow, vertical-walled canyons over bedrock or a veneer of boulders. Waterfalls, deep pools and thermal springs are found along major streams. Elevations range from 600 feet (180 m), where the Big Sur River leaves the Wilderness, to about 5,750 feet (1,750 m) at the wilderness boundary near Junipero Serra Peak.

Geologic features

Pico Blanco, which splits the north and south forks of the Little Sur River, was sacred in the native traditions of the Rumsien and the Esselen, who revered the mountain as a sacred place from which all life originated.[9] The Spanish mission system led to the virtual destruction of the Indian population. Estimates for the pre-contact populations of most native groups in California have varied substantially. Alfred L. Kroeber suggests a 1770 population for the Esselen of 500.[10] Sherburne F. Cook raises this estimate to 750.[11] A more recent calculation (based on baptism records and density) is that they numbered 1,185-1,285.[12]

Flora and fauna

Marked vegetation changes occur within the Wilderness, attributable to dramatic climatic and topographic variations coupled with an extensive fire history. Much of the Ventana is covered by dense communities of chaparral, a group of fire-prone plant species, consisting largely of chamise and various species of manzanita and ceanothus. Other plant communities found in area include oak woodland (Coast Live Oak, Valley Oak, etc.) and pine woodlands (Coulter Pine and Knobcone Pine). Poison oak is found throughout the area. Deep narrow canyons cut by the fast moving Big Sur and Little Sur rivers support stands of coastal redwood (some old growth), Big Leaf Maple, and Sycamore. Small scattered stands of the rare, endemic Bristlecone Fir may be found on rocky slopes and canyon bottoms. Mountain lion, bear, deer, fox and coyotes range the wilderness, as does the California condor, reintroduced to the region by the Ventana Wildlife Society.[13]

Wilderness access

During the 1930s, the United States Civilian Conservation Corp constructed an extensive network of trails and trailheads that provided access to the Wilderness. A number of these are no longer is use.[7] The Pine Ridge trailhead at Big Sur Station near Pfeiffer Big Sur State Park is by far the most popular starting point.[14] Other trailheads include Bottchers Gap, Los Padres Dam, China Camp, and Arroyo Seco. Much of the area is very rugged and trails within the Wilderness are frequently overgrown and challenging to follow. Off-trail travel can be extremely difficult due to the steep, unstable terrain, and dense vegetation, like Madrone, manzanita, and Ceanothus. As is the case in most designated Wilderness areas, motorized equipment and mechanized transport are not allowed. Hunting of feral pigs (Sus scrofa) or European boar, which were introduced into the Carmel Valley area in 1927,[15] is permitted by license.

Government

At the county level, the Ventana Wilderness area is represented on the Monterey County Board of Supervisors by Supervisor Dave Potter.[16]

In the California State Legislature, the Ventana Wilderness is in the 17th Senate District, represented by Democrat Bill Monning, and in the 30th Assembly District, represented by Democrat Anna Caballero.[17] In the United States House of Representatives, the Ventana Wilderness is in California's 20th congressional district, represented by Democrat Sam Farr.[18]

References

- 1 2 "A Brief Land Status History of the Monterey Ranger District". Double Cone Quarterly (Fall 2002 ed.). Ventana Wilderness Society. Retrieved June 22, 2010.

- ↑ "Hiking in Big Sur". Big Sur Chamber of Commerce. Retrieved April 30, 2009.

- ↑ "Cultural History". Ventana Inn. Retrieved August 23, 2016.

- ↑ Analise, Elliott (2005). Hiking & Backpacking Big Sur. Berkeley, California: Wilderness Press. p. 21.

- ↑ Pavlik, Robert C. (November 1996). "Historic Resource Evaluation Report on the Rock Retaining Walls, Parapets, Culvert Headwalls and Drinking Fountains along the Carmel to San Simeon Highway." (PDF). California Department of Transportation. Retrieved August 23, 2016.

- ↑ Henson, Paul (1993). The Natural History of Big Sur (PDF). Donald J. Usner. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-20510-3.

- 1 2 Blakely, Jim; Barnette, Karen (July 1985). Historical Overview: Los Padres National Forest (PDF).

- ↑ "Ventana Wilderness". Bureau Of Land Management. Retrieved 7 September 2016.

- ↑ Elliot, Analise (January 2005). Hiking & Backpacking Big Sur: A Complete Guide to the Trails of Big Sur. Wilderness Press. p. 323. ISBN 0-89997-326-4.

- ↑ Kroeber, p.883

- ↑ Cook, p.186

- ↑ Breschini & Haversat

- ↑ Wright, Tommy (September 1, 2016). "Soberanes Fire could be beneficial for condors". Monterey Herald. Retrieved 4 September 2016.

- ↑ Wilderness.net

- ↑ "Ventana Wilderness Alliance Hunting And Fishing Policy". Ventana Wilderness Society. 27 May 2004. Retrieved 2009-11-01.

- ↑ "Monterey County Supervisorial District 5 Map (North District 5)" (PDF). County of Monterey. Retrieved 21 September 2012.

- ↑ "Statewide Database". UC Regents. Retrieved February 2, 2015.

- ↑ "California's 20th Congressional District - Representatives & District Map". Civic Impulse, LLC.

Further reading

- Hiking the Big Sur Country, Jeffrey P. Schaffer (1988) ISBN 0-89997-083-4

- Map of Ventana Wilderness, Los Padres National Forest, USDA Forest Service (1987)

- Trail Guide to Los Padres National Forest, Ventana Chapter, Sierra Club (2003) ISBN 0-9650652-0-0

External links

- Ventana Wilderness Alliance

- Ventana Chapter, Sierra Club

- Wilderness Areas, Los Padres National Forest

- A Brief Land Status History of the Monterey Ranger District, David Rogers (2002)