Vector notation

| Vector notation | |

|---|---|

| |

| |

Vector notation,[1][2][3] commonly used mathematical notation for working with mathematical vectors,[4] which may be geometric vectors or abstract members of vector spaces.

For representing a vector,[5][6] the common typographic convention is lower case, upright boldface type, as in for a vector named ‘v’. The International Organization for Standardization (ISO) recommends either bold italic serif, as in v or a, or non-bold italic serif accented by a right arrow, as in or .[7] This arrow notation for vectors is commonly used in handwriting, where boldface is impractical. The arrow represents right-pointing arrow notation or harpoons. Shorthand notations include tildes and straight lines placed above or below the name of a vector.

Between 1880 and 1887, Oliver Heaviside developed operational calculus,[8][9] a method of solving differential equations by transforming them into ordinary algebraic equations which caused much controversy when introduced because of the lack of rigour in its derivation.[10] After the turn of the 20th century, Josiah Willard Gibbs would in physical chemistry supply notation for the scalar product and vector products, which was introduced in Vector Analysis.

Rectangular vectors

A rectangular vector is a coordinate vector specified by components that define a rectangle (or rectangular prism in three dimensions, and similar shapes in greater dimensions). The starting point and terminal point of the vector lie at opposite ends of the rectangle (or prism, etc.).

Ordered set notation

A rectangular vector in can be specified using an ordered set of components, enclosed in either parentheses or angle brackets.

In a general sense, an n-dimensional vector v can be specified in either of the following forms:

Where v1, v2, …, vn − 1, vn are the components of v.

Matrix notation

A rectangular vector in can also be specified as a row or column matrix containing the ordered set of components. A vector specified as a row matrix is known as a row vector; one specified as a column matrix is known as a column vector.

Again, an n-dimensional vector can be specified in either of the following forms using matrices:

Where v1, v2, …, vn − 1, vn are the components of v. In some advanced contexts, a row and a column vector have different meaning; see covariance and contravariance of vectors.

Unit vector notation

A rectangular vector in (or fewer dimensions, such as where vz below is zero) can be specified as the sum of the scalar multiples of the components of the vector with the members of the standard basis in . The basis is represented with the unit vectors , , and .

A three-dimensional vector v can be specified in the following form, using unit vector notation:

Where vx, vy, and vz are the magnitudes of the components of v.

Polar vectors

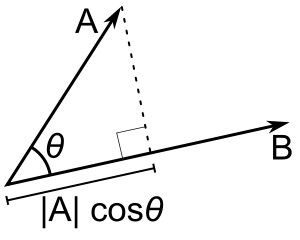

A polar vector is a vector in two dimensions specified as a magnitude (or length) and a direction (or angle). It is akin to an arrow in the polar coordinate system. The magnitude, typically represented as r, is the length from the starting point of the vector to its endpoint. The angle, typically represented as θ (the Greek letter theta), is measured as the offset from the horizontal (or a line collinear with the x-axis in the positive direction). The angle is typically reduced to lie within the range radians or .

Ordered set and matrix notations

Polar vectors can be specified using either ordered pair notation (a subset of ordered set notation using only two components) or matrix notation, as with rectangular vectors. In these forms, the first component of the vector is r (instead of v1) and the second component is θ (instead of v2). To differentiate polar vectors from rectangular vectors, the angle may be prefixed with the angle symbol, .

A two-dimensional polar vector v can be represented as any of the following, using either ordered pair or matrix notation:

Where r is the magnitude, θ is the angle, and the angle symbol () is optional.

Direct notation

Polar vectors can also be specified using simplified autonomous equations that define r and θ explicitly. This can be unwieldy, but is useful for avoiding the confusion with two-dimensional rectangular vectors that arises from using ordered pair or matrix notation.

A two-dimensional vector whose magnitude is 5 units and whose direction is π/9 radians (20°) can be specified using either of the following forms:

Cylindrical vectors

A cylindrical vector is an extension of the concept of polar vectors into three dimensions. It is akin to an arrow in the cylindrical coordinate system. A cylindrical vector is specified by a distance in the xy-plane, an angle, and a distance from the xy-plane (a height). The first distance, usually represented as r or ρ (the Greek letter rho), is the magnitude of the projection of the vector onto the xy-plane. The angle, usually represented as θ or φ (the Greek letter phi), is measured as the offset from the line collinear with the x-axis in the positive direction; the angle is typically reduced to lie within the range . The second distance, usually represented as h or z, is the distance from the xy-plane to the endpoint of the vector.

Ordered set and matrix notations

Cylindrical vectors are specified like polar vectors, where the second distance component is concatenated as a third component to form ordered triplets (again, a subset of ordered set notation) and matrices. The angle may be prefixed with the angle symbol (); the distance-angle-distance combination distinguishes cylindrical vectors in this notation from spherical vectors in similar notation.

A three-dimensional cylindrical vector v can be represented as any of the following, using either ordered triplet or matrix notation:

Where r is the magnitude of the projection of v onto the xy-plane, θ is the angle between the positive x-axis and v, and h is the height from the xy-plane to the endpoint of v. Again, the angle symbol () is optional.

Direct notation

A cylindrical vector can also be specified directly, using simplified autonomous equations that define r (or ρ), θ (or φ), and h (or z). Consistency should be used when choosing the names to use for the variables; ρ should not be mixed with θ and so on.

A three-dimensional vector, the magnitude of whose projection onto the xy-plane is 5 units, whose angle from the positive x-axis is π/9 radians (20°), and whose height from the xy-plane is 3 units can be specified in any of the following forms:

Spherical vectors

A spherical vector is another method for extending the concept of polar vectors into three dimensions. It is akin to an arrow in the spherical coordinate system. A spherical vector is specified by a magnitude, an azimuth angle, and a zenith angle. The magnitude is usually represented as ρ. The azimuth angle, usually represented as θ, is the offset from the line collinear with the x-axis in the positive direction. The zenith angle, usually represented as φ, is the offset from the line collinear with the z-axis in the positive direction. Both angles are typically reduced to lie within the range from zero (inclusive) to 2π (exclusive).

Ordered set and matrix notations

Spherical vectors are specified like polar vectors, where the zenith angle is concatenated as a third component to form ordered triplets and matrices. The azimuth and zenith angles may be both prefixed with the angle symbol (); the prefix should be used consistently to produce the distance-angle-angle combination that distinguishes spherical vectors from cylindrical ones.

A three-dimensional spherical vector v can be represented as any of the following, using either ordered triplet or matrix notation:

Where ρ is the magnitude, θ is the azimuth angle, and φ is the zenith angle.

Direct notation

Like polar and cylindrical vectors, spherical vectors can be specified using simplified autonomous equations, in this case for ρ, θ, and φ.

A three-dimensional vector whose magnitude is 5 units, whose azimuth angle is π/9 radians (20°), and whose zenith angle is π/4 radians (45°) can be specified as:

Operations

In any given vector space, the operations of vector addition and scalar multiplication are defined. Normed vector spaces also define an operation known as the norm (or determination of magnitude). Inner product spaces also define an operation known as the inner product. In , the inner product is known as the dot product. In and , an additional operation known as the cross product is also defined.

Vector addition

Vector addition is represented with the plus sign used as an operator between two vectors. The sum of two vectors u and v would be represented as:

Scalar multiplication

Scalar multiplication is represented in the same manners as algebraic multiplication. A scalar beside a vector (either or both of which may be in parentheses) implies scalar multiplication. The two common operators, a dot and a rotated cross, are also acceptable (although the rotated cross is almost never used), but they risk confusion with dot products and cross products, which operate on two vectors. The product of a scalar c with a vector v can be represented in any of the following fashions:

Vector subtraction and scalar division

Using the algebraic properties of subtraction and division, along with scalar multiplication, it is also possible to “subtract” two vectors and “divide” a vector by a scalar.

Vector subtraction is performed by adding the scalar multiple of −1 with the second vector operand to the first vector operand. This can be represented by the use of the minus sign as an operator. The difference between two vectors u and v can be represented in either of the following fashions:

Scalar division is performed by multiplying the vector operand with the numeric inverse of the scalar operand. This can be represented by the use of the fraction bar or division signs as operators. The quotient of a vector v and a scalar c can be represented in any of the following forms:

Norm

The norm of a vector is represented with double bars on both sides of the vector. The norm of a vector v can be represented as:

The norm is also sometimes represented with single bars, like , but this can be confused with absolute value (which is a type of norm).

Inner product

The inner product (also known as the scalar product, not to be confused with scalar multiplication) of two vectors is represented as an ordered pair enclosed in angle brackets. The inner product of two vectors u and v would be represented as:

Dot product

In , the inner product is also known as the dot product. In addition to the standard inner product notation, the dot product notation (using the dot as an operator) can also be used (and is more common). The dot product of two vectors u and v can be represented as:

In some older literature, the dot product is implied between two vectors written side-by-side. This notation can be confused with the dyadic product between two vectors.

Cross product

The cross product of two vectors (in ) is represented using the rotated cross as an operator. The cross product of two vectors u and v would be represented as:

In some older literature, the following notation is used for the cross product between u and v:

See also

References

- ↑ Principles and Applications of Mathematics for Communications-electronics. Pg 123

- ↑ Notes on fundamentals of telephone transmission. By American Telephone and Telegraph Company. Dept. of development and research. Pg 50

- ↑ Electrical World, Volume 57. McGraw-Hill, 1911. Pg 705

- ↑ Vector Analysis. By Joseph George Coffin.

- ↑ Oliver Heaviside, The Electrical Journal, Volume 28. James Gray, 1892. 109 (alt)

- ↑ Charles Proteus Steinmetz, Theory and Calculation of Alternating Current Phenomena.

- ↑ ISO 80000-2:2009 Quantities and Units—Part 2: Mathematical signs and symbols to be used in the natural sciences and technology, International Organization for Standardization, 2009-12-01

- ↑ The Heaviside Operational Calculus www.quadritek.com/bstj/vol01-1922/articles/bstj1-2-43.pdf

- ↑ Involving the D notation for the differential operator, which he is credited with creating.

- ↑ He famously said, "Mathematics is an experimental science, and definitions do not come first, but later on." He was replying to criticism over his use of operators that were not clearly defined. On another occasion he stated somewhat more defensively, "I do not refuse my dinner simply because I do not understand the process of digestion."