Very Large Telescope

The four Unit Telescopes that form the VLT together with the Auxiliary Telescopes | |

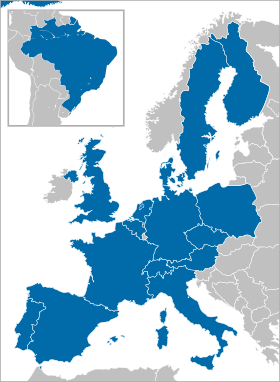

| Organisation | European Southern Observatory |

|---|---|

| Location(s) | Paranal Observatory, Chile |

| Coordinates | 24°37′38″S 70°24′15″W / 24.62733°S 70.40417°WCoordinates: 24°37′38″S 70°24′15″W / 24.62733°S 70.40417°W |

| Altitude | 2,635 m (8,645 ft) |

| Weather | >340 clear nights/year |

| Wavelength | 300 nm – 20 μm (visible, near- and mid-infrared) |

| First light | 1998 (for the first Unit Telescope) |

| Telescope style | Ritchey-Chrétien |

| Diameter |

4 x 8.2-metre Unit Telescopes (UT) 4 x 1.8-metre moveable Auxiliary Telescopes (AT) |

| Mounting | Altazimuth |

| Website |

www |

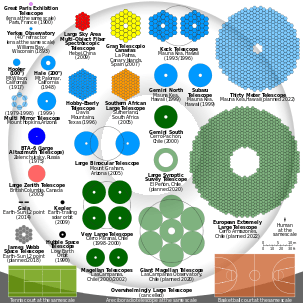

The Very Large Telescope (VLT) is a telescope facility operated by the European Southern Observatory on Cerro Paranal in the Atacama Desert of northern Chile. The VLT consists of four individual telescopes, each with a primary mirror 8.2 m across, which are generally used separately but can be used together to achieve very high angular resolution.[1] The four separate optical telescopes are known as Antu, Kueyen, Melipal and Yepun, which are all words for astronomical objects in the Mapuche language. The telescopes form an array which is complemented by four movable Auxiliary Telescopes (ATs) of 1.8 m aperture.

The VLT operates at visible and infrared wavelengths. Each individual telescope can detect objects roughly four billion times fainter than can be detected with the naked eye, and when all the telescopes are combined, the facility can achieve an angular resolution of about 0.001 arc-second. This is equivalent to roughly 2 meters resolution at the distance of the Moon. In single telescope mode of operation angular resolution is about 0.05 arc-second.[2]

The VLT is the most productive ground-based facility for astronomy, with only the Hubble Space Telescope generating more scientific papers among facilities operating at visible wavelengths.[3] Among the pioneering observations carried out using the VLT are the first direct image of an exoplanet, the tracking of individual stars moving around the supermassive black hole at the centre of the Milky Way, and observations of the afterglow of the furthest known gamma-ray burst.[4]

General information

.jpg)

The VLT consists of an arrangement of four large (8.2 metre diameter) telescopes (called Unit Telescopes or UTs) with optical elements that can combine them into an astronomical interferometer (VLTI), which is used to resolve small objects. The interferometer also includes a set of four 1.8 meter diameter movable telescopes dedicated to interferometric observations. The first of the UTs started operating in May 1998 and was offered to the astronomical community on 1 April 1999. The other telescopes followed suit in 1999 and 2000, thus making the VLT fully operational. Four 1.8-metre Auxiliary Telescopes (ATs) have been added to the VLTI to make it available when the UTs are being used for other projects. These ATs were installed between 2004 and 2007. Today, all four Unit Telescopes and all four Auxiliary Telescopes are operational.[1]

The VLT's 8.2-meter telescopes were originally designed to operate in three modes:[5]

- as a set of four independent telescopes (this is the primary mode of operation).

- as a single large coherent interferometric instrument (the VLT Interferometer or VLTI), for extra resolution. This mode is occasionally used, only for observations of relatively bright sources with small angular extent.

- as a single large incoherent instrument, for extra light-gathering capacity. The instrumentation required to bring the light to a combined incoherent focus was not built. Recently, new instrumentation proposals have been put forward for making this observing mode available.[6] Multiple telescopes are sometimes independently pointed at the same object, either to increase the total light-gathering power, or to provide simultaneous observations with complementary instruments.

Unit telescopes

The UTs are equipped with a large set of instruments permitting observations to be performed from the near-ultraviolet to the mid-infrared (i.e. a large fraction of the light wavelengths accessible from the surface of the Earth), with the full range of techniques including high-resolution spectroscopy, multi-object spectroscopy, imaging, and high-resolution imaging. In particular, the VLT has several adaptive optics systems, which correct for the effects of atmospheric turbulence, providing images almost as sharp as if the telescope were in space. In the near-infrared, the adaptive optics images of the VLT are up to three times sharper than those of the Hubble Space Telescope, and the spectroscopic resolution is many times better than Hubble. The VLTs are noted for their high level of observing efficiency and automation.

The 8.2 m-diameter telescopes are housed in compact, thermally controlled buildings, which rotate synchronously with the telescopes. This design minimises any adverse effects on the observing conditions, for instance from air turbulence in the telescope tube, which might otherwise occur due to variations in the temperature and wind flow.[4]

The principal role of the main VLT telescopes is to operate as four independent telescopes. The interferometry (combining light from multiple telescopes) is used about 20 percent of the time for very high-resolution on bright objects, for example, on Betelgeuse. This mode allows astronomers to see details up to 25 times finer than with the individual telescopes. The light beams are combined in the VLTI using a complex system of mirrors in underground tunnels where the light paths must be kept equal to distances less than 1/1000 mm over a hundred metres. With this kind of precision the VLTI can reconstruct images with an angular resolution of milliarcseconds.[1]

Mapuche names for the Unit Telescopes

It had long been ESO's intention to provide "real" names to the four VLT Unit Telescopes, to replace the original technical designations of UT1 to UT4. In March 1999, at the time of the Paranal inauguration, four meaningful names of objects in the sky in the Mapuche language were chosen. This indigenous people lives mostly south of Santiago de Chile.

An essay contest was arranged in this connection among schoolchildren of the Chilean II Region of which Antofagasta is the capital to write about the implications of these names. It drew many entries dealing with the cultural heritage of ESO's host country.

The winning essay was submitted by 17-year-old Jorssy Albanez Castilla from Chuquicamata near the city of Calama. She received the prize, an amateur telescope, during the inauguration of the Paranal site.[9]

Unit Telescopes 1-4 are since known as Antu (Sun), Kueyen (Moon), Melipal (Southern Cross), and Yepun (Evening Star) respectively.[10] Originally there was some confusion as to whether Yepun actually stands for the evening star Venus, because a Spanish-Mapuche dictionary from the 1940s wrongly translated Yepun as "Sirius".[11]

Auxiliary Telescopes

Although the four 8.2-metre Unit Telescopes can be combined in the VLTI, their observation time is spent mostly used on individual observations, and are used for interferometric observations for a limited number of nights every year. However, the four smaller 1.8-metre ATs are available and dedicated to interferometry to allow the VLTI to operate every night.[4]

The top part of each AT is a round enclosure, made from two sets of three segments, which open and close. Its job is to protect the delicate 1.8-metre telescope from the desert conditions. The enclosure is supported by the boxy transporter section, which also contains electronics cabinets, liquid cooling systems, air-conditioning units, power supplies, and more. During astronomical observations the enclosure and transporter are mechanically isolated from the telescope, to ensure that no vibrations compromise the data collected.[1]

The transporter section runs on tracks, so the ATs can be moved to 30 different observing locations. As the VLTI acts rather like a single telescope as large as the group of telescopes combined, changing the positions of the ATs means that the VLTI can be adjusted according to the needs of the observing project.[1] The reconfigurable nature of the VLTI is similar to that of the Very Large Array.

Scientific results

Results from the VLT have led to the publication of an average of more than one peer-reviewed scientific paper per day. For instance in 2007, almost 500 refereed scientific papers were published based on VLT data.[12] The telescope's scientific discoveries include imaging an extrasolar planet for the first time,[13] tracking individual stars moving around the supermassive black hole at the centre of the Milky Way,[14] and observing the afterglow of the furthest known gamma-ray burst.[15]

Other discoveries with VLT's signature include the detection of carbon monoxide molecules in a galaxy located almost 11 billion light-years away for the first time, a feat that had remained elusive for 25 years. This has allowed astronomers to obtain the most precise measurement of the cosmic temperature at such a remote epoch.[16] Another important study was that of the violent flares from the supermassive black hole at the centre of the Milky Way. The VLT and APEX teamed up to reveal material being stretched out as it orbits in the intense gravity close to the central black hole.[17]

Using the VLT, astronomers have also measured the age of the oldest star known in our galaxy, the Milky Way. At 13.2 billion years old, the star was born in the earliest era of star formation in the Universe.[18] They have also analysed the atmosphere around a super-Earth exoplanet for the first time using the VLT. The planet, which is known as GJ 1214b, was studied as it passed in front of its parent star and some of the starlight passed through the planet’s atmosphere.[19]

In all, of the top 10 discoveries done at ESO's observatories, seven made use of the VLT.[20]

Technical details

Telescopes

Each UT telescope is a Ritchey-Chretien Cassegrain telescope with a 22-tonne 8.2 metre Zerodur primary mirror, and a 1.1 metre lightweight beryllium secondary mirror. A flat tertiary mirror diverts the light to one of two instruments at the f/15 Nasmyth foci on either side, or tilts aside to allow light through the primary mirror central hole to a third instrument at the Cassegrain focus. Additional mirrors can send the light via tunnels to the central VLTI beam-combiners. The maximum field-of-view (at Nasmyth foci) is around 27 arcminutes diameter, slightly smaller than the full moon.

Each telescope has an alt-azimuth mount with total mass around 350 tonnes, and uses active optics with 150 supports on the back of the primary mirror to control the shape of the thin (177mm thick) mirror by computers.

Instruments

.jpg)

The VLT instrumentation programme is the most ambitious programme ever conceived for a single observatory. It includes large-field imagers, adaptive optics corrected cameras and spectrographs, as well as high-resolution and multi-object spectrographs and covers a broad spectral region, from deep ultraviolet (300 nm) to mid-infrared (24 µm) wavelengths.[1]

| UT# | Telescope name | Cassegrain-Focus | Nasmyth-Focus A | Nasmyth-Focus B |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Antu | FORS2 | NACO | KMOS |

| 2 | Kueyen | X-Shooter | FLAMES | UVES |

| 3 | Melipal | VISIR | SPHERE | VIMOS |

| 4 | Yepun | SINFONI | HAWK-I | MUSE |

- AMBER

- The Astronomical Multi-Beam Recombiner instrument is combining three telescopes of the VLT at the same time, dispersing the light in a spectrograph to analyse the composition and shape of the observed object. AMBER is notably the "most-productive interferometric instrument ever".[25]

- CRIRES

- The Cryogenic Infrared Echelle Spectrograph is an adaptive optics assisted echelle spectrograph. It provides a resolving power of up to 100,000 in the infrared spectral range from 1 to 5 micrometres. It is currently undergoing a major upgrade to CRIRES+ to provide 10x larger simultaneous wavelength coverage.

- DAZZLE

- A visitor instrument; guest focus.

- ESPRESSO

- Echelle Spectrograph for Rocky Exoplanet- and Stable Spectroscopic Observations) is a high-resolution, fiber-fed and cross-dispersed echelle spectrograph for the visible wavelength range, capable of operating in 1-UT mode (using one of the four telescopes) and in 4-UT mode (using all four), for the search for rocky extra-solar planets in the habitable zone of their host stars. Its main feature is the spectroscopic stability and the radial-velocity precision. The requirement is to reach 10 cm/s, but the aimed goal is to obtain a precision level of few cm/s. Installation and commissioning of ESPRESSO at the VLT is foreseen in 2016.[26][27]

- FLAMES

- Fibre Large Array Multi-Element Spectrograph is a multi-object fibre feed unit for UVES and GIRAFFE, the latter allowing the capability for simultaneously studying hundreds of individual stars in nearby galaxies at moderate spectral resolution in the visible.

- FORS1/FORS2

- Focal Reducer and Low Dispersion Spectrograph is a visible light camera and Multi Object Spectrograph with a 6.8 arcminute field of view. FORS2 is an upgraded version over FORS1 and includes further multi-object spectroscopy capabilities. FORS1 was retired in 2009 to make space for X-SHOOTER; FORS2 continues to operate as of 2015.[28]

- GRAVITY (VLTI)

- is an adaptive optics assisted, near-infrared (NIR) instrument for micro-arcsecond precision narrow-angle astrometry and interferometric phase referenced imaging of faint celestial objects; expected commissioning will be in 2016. This instrument will interferometrically combine NIR light collected by four telescopes at the VLTI.[29]

- HAWK-I

- The High Acuity Wide field K-band Imager is a near-infrared imager with a relatively large field of view, about 8x8 arcminutes.

- ISAAC

- The Infrared Spectrometer And Array Camera was a near infrared imager and spectrograph; it operated successfully from 2000-2013 and was then retired to make way for SPHERE, since most of its capabilities can now be delivered by the newer HAWK-I or KMOS.

- KMOS

- is a cryogenic near-infrared multi-object spectrometer, observing 24 objects simultaneously, intended primarily for the study of distant galaxies.

- MATISSE (VLTI)

- The Multi Aperture Mid-Infrared Spectroscopic Experiment is an infrared spectro-interferometer of the VLT-Interferometer, which potentially combines the beams of all four Unit Telescopes (UTs) and four Auxiliary Telescopes (ATs). The instrument is used for image reconstruction and under construction as of September 2014. First light at the telescope in Paranal is expected for 2016.[30][31]

- MIDI (VLTI)

- an instrument combining two telescopes of the VLT in the mid-infrared, dispersing the light in a spectrograph to analyse the dust composition and shape of the observed object. MIDI is notably the second most-productive interferometric instrument ever (surpassed by AMBER recently). MIDI was retired in March 2015 to prepare the VLTI for the arrival of GRAVITY and MATISSE.

- MUSE

- is a huge "3-dimensional" spectroscopic explorer which will provide complete visible spectra of all objects contained in "pencil beams" through the Universe.[32]

- NACO

- NAOS-CONICA, NAOS meaning Nasmyth Adaptive Optics System and CONICA, meaning Coude Near Infrared Camera) is an adaptive optics facility which produces infrared images as sharp as if taken in space and includes spectroscopic, polarimetric and coronagraphic capabilities.

- PIONIER (VLTI)

- is an instrument to combine the light of all 8-metre telescopes, allowing to pick up details about 16 times finer than can be seen with one UT.[33]

- SINFONI

- the Spectrograph for Integral Field Observations in the Near Infrared) is a medium resolution, near-infrared (1-2.5 micrometres) integral field spectrograph fed by an adaptive optics module.

- SPHERE

- The Spectro-Polarimetric High-Contrast Exoplanet Research, a high-contrast adaptive optics system dedicated to the discovery and study of exoplanets.[34][35]

- ULTRACAM

- is a visitor instrument

- UVES

- The Ultraviolet and Visual Echelle Spectrograph is a high-resolution ultraviolet and visible light echelle spectrograph.

- VIMOS

- The Visible Multi-Object Spectrograph delivers visible images and spectra of up to 1,000 galaxies at a time in a 14 x 14 arcmin field of view.

- VINCI

- was a test instrument combining two telescopes of the VLT. It was the first-light instrument of the VLTI and is not longer in use

- VISIR

- The VLT spectrometer and imager for the mid-infrared) provides diffraction-limited imaging and spectroscopy at a range of resolutions in the 10 and 20 micrometre mid-infrared (MIR) atmospheric windows.

- X-Shooter

- is the first second-generation instrument, a very wide-band [UV to near infrared] single-object spectrometer designed to explore the properties of rare, unusual or unidentified sources

Interferometry

In its interferometric operating mode, the light from the telescopes is reflected off mirrors and directed through tunnels to a central beam combining laboratory. In the year 2001, during commissioning, the VLTI successfully measured the angular diameters of four red dwarfs including Proxima Centauri. During this operation it achieved an angular resolution of ±0.08 milli-arc-seconds. This is comparable to the resolution achieved using other arrays such as the Navy Prototype Optical Interferometer and the CHARA array. Unlike many earlier optical and infrared interferometers, the Astronomical Multi-Beam Recombiner (AMBER) instrument on VLTI was initially designed to perform coherent integration (which requires signal-to-noise greater than one in each atmospheric coherence time). Using the big telescopes and coherent integration, the faintest object the VLTI can observe is magnitude 7 in the near infrared for broadband observations,[37] similar to many other near infrared / optical interferometers without fringe tracking2. In 2011, an incoherent integration mode was introduced [38] called AMBER "blind mode", which is more similar to the observation mode used at earlier interferometer arrays such as COAST, IOTA and CHARA. In this "blind mode", AMBER can observe sources as faint as K=10 in medium spectral resolution. At more challenging mid-infrared wavelengths, the VLTI can reach magnitude 4.5, significantly fainter than the Infrared Spatial Interferometer. When fringe tracking is introduced, the limiting magnitude of the VLTI is expected to improve by a factor of almost 1000, reaching a magnitude of about 14. This is similar to what is expected for other fringe tracking interferometers. In spectroscopic mode, the VLTI can currently reach a magnitude of 1.5. The VLTI can work in a fully integrated way, so that interferometric observations are actually quite simple to prepare and execute. The VLTI has become worldwide the first general user optical/infrared interferometric facility offered with this kind of service to the astronomical community.[39]

Because of the many mirrors involved in the optical train, about 95 percent of the light is lost before reaching the instruments at a wavelength of 1 µm, 90 percent at 2 µm and 75 percent at 10 µm.[40] This refers to reflection off 32 surfaces including the Coudé train, the star separator, the main delay line, beam compressor and feeding optics. Additionally, the interferometric technique is such that it is very efficient only for objects that are small enough that all their light is concentrated. For instance, an object with a relatively low surface brightness such as the moon cannot be observed, because its light is too diluted. Only targets which are at temperatures of more than 1,000°C have a surface brightness high enough to be observed in the mid-infrared, and objects must be at several thousands of degrees Celsius for near-infrared observations using the VLTI. This includes most of the stars in the solar neighborhood and many extragalactic objects such as bright active galactic nuclei, but this sensitivity limit rules out interferometric observations of most solar-system objects. Although the use of large telescope diameters and adaptive optics correction can improve the sensitivity, this cannot extend the reach of optical interferometry beyond nearby stars and the brightest active galactic nuclei.

Because the Unit Telescopes are used most of the time independently, they are used in the interferometric mode mostly during bright time (that is, close to Full Moon). At other times, interferometry is done using 1.8 meter Auxiliary Telescopes (ATs), which are dedicated to full-time interferometric measurements. The first observations using a pair of ATs were conducted in February 2005, and all the four ATs have now been commissioned. For interferometric observations on the brightest objects, there is little benefit in using 8 meter telescopes rather than 1.8 meter telescopes.

The first two instruments at the VLTI were VINCI (a test instrument used to set up the system, now decommissioned) and MIDI,[41] which only allow two telescopes to be used at any one time. With the installation of the three-telescope AMBER closure-phase instrument in 2005, the first imaging observations from the VLTI are expected soon.

Deployment of The Phase Referenced Imaging and Microarcsecond Astrometry (PRIMA) instrument started 2008 with the aim to allow phase-referenced measurements in either an astrometric two-beam mode or as a fringe-tracker successor to VINCI, operated concurrent with one of the other instruments.[42][43][44]

After falling drastically behind schedule and failing to meet some specifications, in December 2004 the VLT Interferometer became the target of a second ESO "recovery plan". This involves additional effort concentrated on improvements to fringe tracking and the performance of the main delay lines. Note that this only applies to the interferometer and not other instruments on Paranal. In 2005, the VLTI was routinely producing observations, although with a brighter limiting magnitude and poorer observing efficiency than expected.

As of March 2008, the VLTI had already led to the publication of 89 peer-reviewed publications[45] and had published a first-ever image of the inner structure of the mysterious Eta Carinae.[46] In March 2011, the PIONIER instrument for the first time simultaneously combined the light of the four Unit Telescopes, potentially making VLTI the biggest optical telescope in the world.[33] However, this attempt was not really a success.[47] The first successful attempt was in February 2012, with four telescopes combined into a 130-meter diameter mirror.[47]

In popular culture

One of the large mirrors of the telescopes was the subject of an episode of the National Geographic Channel's reality series World's Toughest Fixes, where a crew of engineers removed and transported the mirror to be cleaned and re-coated with aluminium. The job required battling strong winds, fixing a broken pump in a giant washing machine and resolving a rigging issue.

The area surrounding the Very Large Telescope has also been featured in a blockbuster movie. The ESO Hotel, the Residencia, is an award-winning building, and served as a backdrop for part of the James Bond movie Quantum of Solace.[4] The movie producer, Michael G. Wilson, said: “The Residencia of Paranal Observatory caught the attention of our director, Marc Forster and production designer, Dennis Gassner, both for its exceptional design and its remote location in the Atacama desert. It is a true oasis and the perfect hide out for Dominic Greene, our villain, whom 007 is tracking in our new James Bond film.”[48]

Gallery

VLT’s Laser Guide Star in action.[49]

VLT’s Laser Guide Star in action.[49] Bird’s Eye View of the Very Large Telescope

Bird’s Eye View of the Very Large Telescope Laser guide star used on one of the UTs

Laser guide star used on one of the UTs

The triplet of galaxies NGC 6769, 6770 and NGC 6771, as observed with the VIMOS instrument on Melipal

The triplet of galaxies NGC 6769, 6770 and NGC 6771, as observed with the VIMOS instrument on Melipal A storm on Saturn observed by the VLT

A storm on Saturn observed by the VLT The Sombrero Galaxy as seen by the VLT's FORS1 instrument

The Sombrero Galaxy as seen by the VLT's FORS1 instrument The central 5,500 light-years wide region of the spiral galaxy NGC 1097, obtained with the NACO adaptive optics on the VLT

The central 5,500 light-years wide region of the spiral galaxy NGC 1097, obtained with the NACO adaptive optics on the VLT One of the first images from the VIMOS facility, showing the famous "Antennae Galaxies" (NGC 4038/9)

One of the first images from the VIMOS facility, showing the famous "Antennae Galaxies" (NGC 4038/9) VLT image of the nebula LHA 120-N 44 surrounding the star cluster NGC 1929

VLT image of the nebula LHA 120-N 44 surrounding the star cluster NGC 1929 The nebula around the bright red supergiant star Betelgeuse taken with the VLT's VISIR infrared camera

The nebula around the bright red supergiant star Betelgeuse taken with the VLT's VISIR infrared camera The star cluster and surrounding nebula NGC 371 taken using the FORS1 instrument on the VLT

The star cluster and surrounding nebula NGC 371 taken using the FORS1 instrument on the VLT The 2010 Perseids meteor shower over the VLT

The 2010 Perseids meteor shower over the VLT All four of the VLT's unit telescopes can be seen operating independently in this time-lapse video.

All four of the VLT's unit telescopes can be seen operating independently in this time-lapse video. Short video about the SPHERE instrument being installed in 2014.

Short video about the SPHERE instrument being installed in 2014. Darkness covers the Paranal sky in this time-lapse video showing the stars wheeling overhead and one of the VLT's Unit Telescopes making observations.

Darkness covers the Paranal sky in this time-lapse video showing the stars wheeling overhead and one of the VLT's Unit Telescopes making observations. A time-lapse taken in the early hours of the morning at Paranal showing the VLT Unit Telescopes making a series of independent observations.

A time-lapse taken in the early hours of the morning at Paranal showing the VLT Unit Telescopes making a series of independent observations. This video sequence shows the four beams emerging from the new laser system on Unit Telescope 4 of the VLT.

This video sequence shows the four beams emerging from the new laser system on Unit Telescope 4 of the VLT..webm.jpg) Infrared images of Jupiter captured using the VISIR instrument.

Infrared images of Jupiter captured using the VISIR instrument.

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Very Large Telescope. |

- Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory

- European Extremely Large Telescope

- Extremely large telescope

- La Silla Observatory

- List of largest optical reflecting telescopes

- Llano de Chajnantor Observatory

- Mauna Kea Observatories

- Overwhelmingly Large Telescope

- Paranal Observatory

- Roque de los Muchachos Observatory

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "The Very Large Telescope". ESO. Retrieved 2011-08-05.

- ↑ http://www.eso.org/public/about-eso/faq/faq-vlt-paranal/

- ↑ Trimble, V.; Ceja, J. A. (2010). "Productivity and impact of astronomical facilities: A recent sample". Astronomische Nachrichten. 331 (3): 338. Bibcode:2010AN....331..338T. doi:10.1002/asna.200911339.

- 1 2 3 4 "The Very Large Telescope — The World's Most Advanced Visible-light Astronomical Observatory handout". ESO. Retrieved 2011-08-05.

- ↑ "Science with the VLT in the ELT Era" (PDF). Retrieved 2013-06-17.

- ↑ Pasquini, Luca; Manescau, A.; Avila, G.; et al. (2009). Moorwood, Alan, ed. "Science with the VLT in the ELT Era — ESPRESSO: A High Resolution Spectrograph for the Combined Coudé Focus of the VLT" (PDF). Astrophysics and Space Science Proceedings. Dordrecht: Springer Science+Business Media B.V.: 395–399. Bibcode:2009ASSP....9..395P. doi:10.1007/978-1-4020-9190-2_68. ISBN 978-1-4020-9189-6. ISSN 1570-6591. Retrieved May 26, 2013.

- ↑ "Getting the VLT Ready for Even Sharper Images". ESO Picture of the Week. Retrieved 14 May 2012.

- ↑ "The Strange Case of the Missing Dwarf". ESO Press Release. European Southern Observatory. Retrieved 27 February 2015.

- ↑ "VLT Unit Telescopes Named at Paranal Inauguration". ESO. 6 March 1999. Retrieved 2011-05-04.

- ↑ "Names of VLT Unit Telescopes". Retrieved 2011-05-04.

- ↑ "On the Meaning of "YEPUN"". Retrieved 2011-05-04.

- ↑ "ESO Science Library". Retrieved 2011-05-04.

- ↑ "Beta Pictoris planet finally imaged?". ESO. 21 November 2008. Retrieved 2011-05-04.

- ↑ "Unprecedented 16-Year Long Study Tracks Stars Orbiting Milky Way Black Hole". ESO. 10 December 2008. Retrieved 2011-05-04.

- ↑ "NASA's Swift Catches Farthest Ever Gamma-Ray Burst". NASA. 19 September 2008. Retrieved 2011-05-04.

- ↑ "A Molecular Thermometer for the Distant Universe". ESO. 13 May 2008. Retrieved 2011-04-05.

- ↑ "Astronomers detect matter torn apart by black hole". ESO. 18 October 2008. Retrieved 2011-04-05.

- ↑ "How Old is the Milky Way?". ESO. 17 August 2004. Retrieved 2011-04-05.

- ↑ "VLT Captures First Direct Spectrum of an Exoplanet". ESO. 13 January 2010. Retrieved 2011-04-05.

- ↑ "ESO Top 10 Astronomical Discoveries". ESO. Retrieved 2011-08-05.

- ↑ "Exoplanet Imager SPHERE Shipped to Chile". ESO. 18 February 2014. Retrieved 12 March 2014.

- ↑ "24-armed Giant to Probe Early Lives of Galaxies". ESO Press Release. Retrieved 12 December 2012.

- ↑ "VLT Instruments". Retrieved 2011-08-05.

- ↑ "Paranal Observatory Instrumentation". Retrieved 2015-10-09.

- ↑ "most-productive interferometric instrument ever". Archived from the original on June 9, 2015.

- ↑ "Espresso". Espresso.astro.up.pt. Retrieved 2013-06-17.

- ↑ "ESO - ESPRESSO". eso.org. Retrieved 2015-10-05.

- ↑ "FORS - FOcal Reducer and low dispersion Spectrograph". ESO. 7 September 2014.

- ↑ "GRAVITY". mpe.mpg.de. Retrieved 2014-02-23.

- ↑ "MATISSE (the Multi AperTure mid-Infrared SpectroScopic Experiment)". ESO. 25 September 2014. Retrieved 3 July 2015.

- ↑ "An Overview of the MATISSE Instrument—Science, Concept and Current Status" (PDF). Matisse consortium. 14 September 2014.

- ↑ "Muse". ESO. Retrieved 2013-06-17.

- 1 2 "ann11021 - Light from all Four VLT Unit Telescopes Combined for the First Time". ESO. 2011-04-20. Retrieved 2013-06-17.

- ↑ "Sphere". ESO. Retrieved 2015-07-02.

- ↑ http://www.eso.org/public/news/eso1417/

- ↑ http://www.eso.org, announcement-11021, Light from all Four VLT Unit Telescopes Combined for the First Time, 20 April 2011

- ↑ "AMBER - Astronomical Multi-BEam combineR". Eso.org. Retrieved 2013-06-17.

- ↑ "AMBER "blind mode"". Fizeau.oca.eu. 2012-01-01. Retrieved 2013-06-17.

- ↑ hboffin@eso.org (2006-06-29). "Observing with the ESO VLT Interferometer". Eso.org. Retrieved 2013-06-17.

- ↑ Puech, F.; Gitton, P. (2006). "Interface Control Document between VLTI and its instruments". VLT-ICD-ESO-15000-1826.

- ↑ "Mid-Infrared Interferometric instrument". Eso.org. Retrieved 2013-06-17.

- ↑ Sahlmann, J.; Ménardi, S.; Abuter, R; Accardo, M.; Mottini, S.; Delplancke, F. (2009). "The PRIMA fringe sensor unit". Astron. Astrophys. 507 (3): 1739–1757. arXiv:0909.1470

. Bibcode:2009A&A...507.1739S. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/200912271.

. Bibcode:2009A&A...507.1739S. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/200912271. - ↑ Delplancke, Francoise (2008). "The PRIMA facility phase-referenced imaging and micro-arcsecond astrometry". New Astr. Rev. 52 (2–5): 189–207. Bibcode:2008NewAR..52..199D. doi:10.1016/j.newar.2008.04.016.

- ↑ Sahlmann, J.; Abuter, R.; Menardi, S.; Schmid, C.; Di Lieto, N.; Delplancke, F.; Frahm, R.; Gomes, N.; Haguenauer, P.; et al. (2010). Danchi, William C; Delplancke, Françoise; Rajagopal, Jayadev K, eds. "First results from fringe tracking with the PRIMA fringe sensor unit". Proc. SPIE. Optical and Infrared Interferometry II. 7734 (7734): 773422–773422–12. arXiv:1012.1321

. Bibcode:2010SPIE.7734E..62S. doi:10.1117/12.856896.

. Bibcode:2010SPIE.7734E..62S. doi:10.1117/12.856896. - ↑ "ESO Telescope Bibliography". Archive.eso.org. Retrieved 2013-06-17.

- ↑ "eso0706b - The Inner Winds of Eta Carinae". ESO. 2007-02-23. Retrieved 2013-06-17.

- 1 2 Moskvitch, Katia (2012-02-03). "K. Moskvitch - Four telescope link-up creates world's largest mirror (2012)". BBC. Retrieved 2013-06-17.

- ↑ "A Giant of Astronomy and a Quantum of Solace: Blockbuster shooting in Paranal". ESO. 25 March 2008. Retrieved 2011-08-05.

- ↑ "1001 Stars". www.eso.org. Retrieved 26 September 2016.

- ↑ "Capturing the Ultra High Definition Universe". ESO. Retrieved 2 April 2014.

External links

- Visits to the Paranal Site

- ESO VLT official site for the 8 m and 1.8 m telescopes.

- ESO VLTI official site for the interferometer (combining the telescopes)

- Delay Lines for the Very Large Telescopes @Dutch Space

- ASTROVIRTEL Accessing Astronomical Archives as Virtual Telescopes including archives from the VLT

- Travelogue VLT Visit

- VLT images

- World's Toughest Fixes

- Bond@Paranal website.