Haight-Ashbury

| Haight-Ashbury | |

|---|---|

| Neighborhood | |

|

Cole Street, left, and Haight Street, right | |

| Nickname(s): The Haight, Upper Haight, Hashbury,[1] Psychedelphia[1] | |

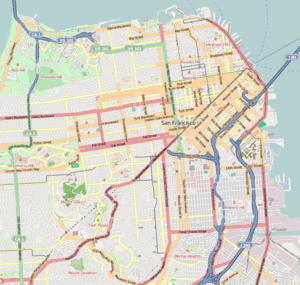

Haight-Ashbury Location within Central San Francisco | |

| Coordinates: 37°46′12″N 122°26′49″W / 37.7700°N 122.4469°WCoordinates: 37°46′12″N 122°26′49″W / 37.7700°N 122.4469°W | |

| Country |

|

| State |

|

| City and county | San Francisco |

| Government | |

| • Supervisor | London Breed |

| • Assemblymember | David Chiu (D)[2] |

| • State senator | Scott Wiener (D)[2] |

| • U. S. rep. | Nancy Pelosi (D)[3] |

| Area[4] | |

| • Total | 0.309 sq mi (0.80 km2) |

| • Land | 0.309 sq mi (0.80 km2) |

| Population [4] | |

| • Total | 10,601 |

| • Density | 34,253/sq mi (13,225/km2) |

| Time zone | Pacific (UTC−8) |

| • Summer (DST) | PDT (UTC−7) |

| ZIP code | 94117 |

| Area codes | 415/628 |

Haight-Ashbury is a district of San Francisco, California, named for the intersection of Haight and Ashbury streets. It is also called The Haight and The Upper Haight.[5] The neighborhood is known for its history of, and being the origin of hippie counterculture.

Location

The district generally encompasses the neighborhood surrounding Haight Street, bounded by Stanyan Street and Golden Gate Park on the west, Oak Street and the Golden Gate Park Panhandle on the north, Baker Street and Buena Vista Park to the east and Frederick Street and Ashbury Heights and Cole Valley neighborhoods to the south.

The street names commemorate two early San Francisco leaders: Pioneer and exchange banker Henry Haight[6] and Munroe Ashbury, a member of the San Francisco Board of Supervisors from 1864 to 1870.[7] Both Haight and his nephew as well as Ashbury had a hand in the planning of the neighborhood, and, more importantly, nearby Golden Gate Park at its inception. The name "Upper Haight", used by locals, is in contrast to the Haight-Fillmore or Lower Haight district; the latter being lower in elevation and part of what was previously the principal African-American and Japanese neighborhoods in San Francisco's early years.

The Haight-Ashbury district is noted for its role as a center of the 1960s hippie movement. The earlier bohemians of the beat movement had congregated around San Francisco's North Beach neighborhood from the late 1950s. Many who could not find accommodation there turned to the quaint, relatively cheap and underpopulated Haight-Ashbury.[8] The Summer of Love (1967), the 1960s era as a whole, and much of modern American counterculture have been synonymous with San Francisco and the Haight-Ashbury neighborhood ever since.

History

Farms, entertainment, and homes

Before the completion of the Haight Street Cable Railroad in 1883, what is now the Haight-Ashbury was a collection of isolated farms and acres of sand dunes. The Haight cable car line, completed in 1883, connected the east end of Golden Gate Park with the geographically central Market Street line and the rest of downtown San Francisco. As the primary gateway to Golden Gate Park, and with an amusement park known as the Chutes[9] on Haight Street between Cole and Clayton Streets between 1895 and 1902[10] and the California League Baseball Grounds stadium opening in 1887, the area became a popular entertainment destination, especially on weekends. The cable car, land grading and building techniques of the 1890s and early 20th century later reinvented the Haight-Ashbury as a residential upper middle class homeowners' district.[11] It was one of the few neighborhoods spared from the fires that followed the catastrophic San Francisco earthquake of 1906.

Depression and war

The Haight was hit hard by the Depression, as was much of the city. Residents with enough money to spare left the declining and crowded neighborhood for greener pastures within the growing city limits, or newer, smaller suburban homes in the Bay Area. During the housing shortage of World War II, large single-family Victorians were divided into apartments to house workers. Others were converted into boarding homes for profit. By the 1950s, the Haight was a neighborhood in decline. Many buildings were left vacant after the war. Deferred maintenance also took its toll, and the exodus of middle class residents to newer suburbs continued to leave many units for rent.

Postwar

In the 1950s, a freeway was proposed that would have run through the Panhandle, but due to a citizen freeway revolt, it was cancelled in a series of battles that lasted until 1966.[12][13] The Haight Ashbury Neighborhood Council (HANC) was formed at the time of the 1959 revolt.[14] HANC is still active in the neighborhood as of 2008.[15]

The Haight-Ashbury's elaborately detailed, 19th century, multi-story, wooden houses became a haven for hippies during the 1960s, due to the availability of cheap rooms and vacant properties for rent or sale in the district; property values had dropped in part because of the proposed freeway.[16] The bohemian subculture that subsequently flourished there took root, and to a great extent, has remained to this day.[17]

Hippie Community

The mainstream media's coverage of hippie life in the Haight-Ashbury drew the attention of youth from all over America. Hunter S. Thompson labeled the district "Hashbury" in The New York Times Magazine, and the activities in the area were reported almost daily.[18] The Haight-Ashbury district was sought out by hippies to constitute a community based upon counterculture ideals, drugs, and music. This neighborhood offered a concentrated gathering spot for hippies to create a social experiment that would soon spread throughout the nation.[19] The opening of the Psychedelic Shop on January 3, 1966 offered hippies a spot to purchase marijuana and LSD, which was essential to hippie life in Haight-Ashbury.[20] With the Psychedelic Shop located in the heart of Haight-Ashbury, the entire hippie community had easy access to drugs, which was perceived as a community unifier.[21] The neighborhood's fame reached its peak as it became the haven for a number of the top psychedelic rock performers and groups of the time. Acts such as Jefferson Airplane, the Grateful Dead, and Janis Joplin all lived a short distance from the intersection. They not only immortalized the scene in song, but also knew many within the community as friends and family.

The first ever head shop, Ron and Jay Thelin's Psychedelic Shop, opened on Haight Street in January 1966. Along with businesses like the coffee shop the Blue Unicorn, the Psychedelic Shop quickly became one of the unofficial community centers for the growing numbers of freaks, heads, and hippies migrating to the neighborhood in 1966-67.[22]

Another well-known neighborhood presence was the Diggers, a local "community anarchist" group known for its street theater, formed in the mid to late 1960s. The Diggers believed in a free society and the good in human nature. To express their belief, they established a free store, gave out free meals daily, and built a free medical clinic, which was the first of its kind, all of which functioned off of volunteers and donations.[23] The Diggers were strongly opposed to a capitalistic society (Hill 69); they felt that by eliminating the need for money, people would be free to examine their own personal values, which would provoke people to change the way they lived to better suit their character, and thus lead a happier life.[24]

During the "Summer of Love," psychedelic rock music was entering the mainstream, receiving more and more commercial radio airplay. The Scott McKenzie song "San Francisco (Be Sure to Wear Flowers in Your Hair)," written by John Phillips of The Mamas & the Papas, became a hit single in 1967. The Monterey Pop Festival in June further cemented the status of psychedelic music as a part of mainstream culture and elevated local Haight bands such as the Grateful Dead, Big Brother and the Holding Company, and Jefferson Airplane to national stardom. A July 7, 1967, Time magazine cover story on "The Hippies: Philosophy of a Subculture," an August CBS News television report on "The Hippie Temptation"[25] and other major media interest in the hippie subculture exposed the Haight-Ashbury district to enormous national attention and popularized the counterculture movement across the country and around the world.

The Summer of Love attracted a wide range of people of various ages: teenagers and college students drawn by their peers and the allure of joining a cultural utopia; middle-class vacationers; and even partying military personnel from bases within driving distance. The Haight-Ashbury could not accommodate this rapid influx of people, and the neighborhood scene quickly deteriorated. Overcrowding, homelessness, hunger, drug problems, and crime afflicted the neighborhood. Many people simply left in the fall to resume their college studies.[24] On October 6, 1967, those remaining in the Haight staged a mock funeral, "The Death of the Hippie" ceremony.[26] Mary Kasper explained the message of the mock funeral as follows:

We wanted to signal that this was the end of it, don't come out. Stay where you are! Bring the revolution to where you live. Don't come here because it's over and done with.[27]

Recent history

After 1968, the area went into decline due to "an influx of hard drugs and a lack of police presence,"[28][29] but was improved and renewed in the late 1970s.[30]

Throughout the 1980s, the Haight became an epicenter for the SF Comedy Scene when a small coffee house off Haight Street called The Other Café[31] (currently the restaurant Crepes on Cole) became a full-time comedy club that helped launch the careers of Robin Williams, Dana Carvey, and Whoopi Goldberg.[32] Also in the 1980s through the early 1990s, the I-Beam nightclub on Haight Street became a hot spot for modern rock dance music in San Francisco, and a popular venue for live performances by a litany of the world's best known new wave, punk, industrial, and indie bands.

Attractions and characteristics

The Red Victorian hotel is a popular attraction. An independent theater of the same name operated about a block away from the hotel from 1980 to 2011.[33]

The Haight-Ashbury Street Fair is held on the second Sunday of June each year attracting thousands of people, during which Haight Street is closed between Stanyan and Masonic to vehicular traffic, with one sound stage at each end.[34]

See also

- Chinese Immersion School at De Avila

- Counterculture of the 1960s

- Haight Ashbury Free Clinics

- Haight-Ashbury Switchboard

- Haight Street Grounds

- I-Beam (nightclub)

- Kerista Commune

- Magnolia Thunderpussy

- The Process Church of The Final Judgment (religious movement formerly based in Haight-Ashbury)

- The Red Victorian

References

- 1 2 Spann, Edward K. (2003). Democracy's Children: The Young Rebels of the 1960s and the Power of Ideals. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 111.

- 1 2 "Statewide Database". UC Regents. Retrieved November 4, 2014.

- ↑ "California's 12th Congressional District - Representatives & District Map". Civic Impulse, LLC.

- 1 2 "Haigh-Ashbury neighborhood in San Francisco, California (CA), 94117 subdivision profile". City-Data.com. Retrieved January 5, 2015.

- ↑ SFStation.com

- ↑ "San Francisco Streets Named for Pioneers". Museum of the City of San Francisco. Retrieved 2007-06-01.

- ↑ Loewenstein, Louis (1984). Streets of San Francisco: The Origins of Street & Place Names. San Francisco: Lexikos. p. 5. ISBN 0-938530-27-5.

- ↑ Gilliland, John (1969). "Show 42 - The Acid Test: Defining 'hippy'" (audio). Pop Chronicles. Digital.library.unt.edu. Track 1.

- ↑ "The Chutes - FoundSF". March 1998. Retrieved Mar 31, 2013.

- ↑ "Old 21 - Neighborhood - The Chutes". Retrieved Mar 30, 2013.

- ↑ "Old 21 - Neighborhood - Haight Ashbury". Retrieved Mar 30, 2013.

- ↑ Adams, Gerald (2003-03-28). "Farewell to freeway: Decades of revolt force Fell Street off-ramp to fall". San Francisco Chronicle.

- ↑ Starr, Jerold (1985). Cultural Politics: Radical Movements in Modern History. Praeger. ISBN 978-0-03-062522-0.

- ↑ Rodriguez, Joseph (1999). City Against Suburb: The Culture Wars in an American Metropolis. Praeger. p. 40. ISBN 978-0-275-96406-1.

- ↑ Nevius, C. W. (2008-10-28). "New community activists flex muscle in Haight". San Francisco Chronicle.

- ↑ Ashbolt, Anthony (December 2007). "'Go Ask Alice': Remembering the Summer of Love Forty Years On" (PDF). Australasian Journal of American Studies. 26 (2): 35.

- ↑ White, Dan (2009-01-09). "In San Francisco, Where Flower Power Still Blooms". The New York Times.

- ↑ T. Anderson, The Movement and the Sixties: Protest in America from Greensboro to Wounded Knee, (Oxford University Press, 1995), p.174

- ↑ Ashbolt, Anthony. "'Go Ask Alice': Remembering the Summer of Love Forty Years On". JSTOR. JSTOR, n.d. Web. 2 Mar. 2014.

- ↑ Tamony, Peter. "Tripping out in San Francisco". American Speech. 2nd ed. Vol. 56. N.p.: Duke UP, n.d. 98-103. JSTOR. Web. 13 Mar. 2014.

- ↑ Ashbolt, Anthony. "From Haight-Ashbury to Soulful Socialism: Culture and Politics in the Movement". Australasian Journal of American Studies. 3rd ed. Vol. 1. N.p.: Australia and New Zealand American Studies Association, n.d. 28-38. JSTOR. Web. 13 Mar. 2014.

- ↑ Joshua Clark Davis, The Business of Getting High: Head Shops, Countercultural Capitalism, and the Marijuana Legalization Movement, The Sixties: A Journal of Politics, Culture and Society, Summer 2015

- ↑ Miles, Barry (2004). Hippie. New York: Sterling.

- 1 2 Gail Dolgin; Vicente Franco (2007). American Experience: The Summer of Love. PBS. Retrieved 2007-04-23.

- ↑ http://www.sfsu.edu/~avitv/avcatalog/88444.htm

- ↑ "The Year of the Hippie: Timeline". PBS.org. Retrieved 2007-04-24..

- ↑ "Transcript (for American Experience documentary on the Summer of Love)". PBS and WGBH. 2007-03-14.

- ↑ Katherine Powell Cohen (2008). San Francisco's Haight-Ashbury. Arcadia Publishing. p. 77. ISBN 9780738559940.

- ↑ "Calm has descended on Haight-Ashbury". The Milwaukee Journal. UPI. 17 December 1979. p. 4.

But by winter, with drug pushers moving into the neighborhood in force, the Haight abruptly turned into a teenage slum of robbers, rapists, and speed freaks.

- ↑ "Haight-Ashbury (district, San Francisco, California, United States)". Britannica Online Encyclopedia. Retrieved 30 October 2012.

- ↑ The Other Cafe

- ↑ "The Other Cafe Story". 2011. Retrieved Mar 30, 2013.

- ↑ Johnson, G. Allen (July 7, 2011). "Red Vic Movie House in San Francisco to Close". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved August 14, 2011.

- ↑ Street Fair website

Further reading

- Joshua Clark Davis, The Business of Getting High: Head Shops, Countercultural Capitalism, and the Marijuana Legalization Movement, The Sixties: A Journal of Politics, Culture and Society, Summer 2015

- Cohen, Katherine Powell. San Francisco's Haight-Ashbury. Arcadia Publishers, 2008

- Perry, Charles. The Haight-Ashbury: A History. Wenner Books, 2005. Original publication: 1984

External links

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for San Francisco/Haight. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Haight-Ashbury, San Francisco. |

- The Haight-Ashbury 30 Years Ago: A Timeline

- The Maze: Haight/Ashbury – 1967 KPIX-TV documentary about the Haight-Ashbury district presented by writer Michael McClure, from the Digital Information Virtual Archive at San Francisco State University

- Who's Who of the Haight-Ashbury Era

Geographic situation within San Francisco

|

Richmond District | North Panhandle | Alamo Square |

| |||

| |

|||||||

| Golden Gate Park | |

Lower Haight | |||||

| |

Duboce Triangle | ||||||

| Sunset District | Cole Valley | Castro |

.svg.png)