National Weather Service

| |

| Agency overview | |

|---|---|

| Formed | February 9, 1870[1] |

| Preceding agency |

|

| Jurisdiction | Federal government of the United States |

| Headquarters | Silver Spring, Maryland |

| Employees | 5,000[3] |

| Annual budget | $1,124,149,000[4] |

| Agency executive |

|

| Parent agency | NOAA |

| Child agency | |

| Website |

www |

The National Weather Service (NWS) is an agency of the United States government, which is a part of the United States department of Commerce that is tasked with providing weather forecasts, warnings of hazardous weather, and other weather-related products to organizations and the public for the purposes of protection, safety, and general information. It is a part of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) branch of the Department of Commerce, and is headquartered in Silver Spring, Maryland (located just outside Washington, D.C.).[5][6] The agency was known as the United States Weather Bureau from 1870 until it adopted its current name in 1970.[7]

The NWS performs its primary task through a collection of national and regional centers, and 123 local weather forecast offices (WFOs). As the NWS is a government agency, most of its products are in the public domain and available free of charge.

History

_in_Silver_Spring%2C_Montgomery_County%2C_Maryland.jpg)

In 1870, the Weather Bureau of the United States was established through a joint resolution of Congress signed by President Ulysses S. Grant[8] with a mission to "provide for taking meteorological observations at the military stations in the interior of the continent and at other points in the States and Territories...and for giving notice on the northern (Great) Lakes and on the seacoast by magnetic telegraph and marine signals, of the approach and force of storms." The agency was placed under the Secretary of War as Congress felt "military discipline would probably secure the greatest promptness, regularity, and accuracy in the required observations." Within the Department of War, it was assigned to the U.S. Army Signal Service under Brigadier General Albert J. Myer. General Myer gave the National Weather Service its first name: The Division of Telegrams and Reports for the Benefit of Commerce.[9]

Cleveland Abbe – who began developing probabilistic forecasts using daily weather data sent by the Cincinnati Chamber of Commerce and Western Union, which he convinced to back the collection of such information in 1869 – was appointed as the Bureau's first chief meteorologist. In his earlier role as the civilian assistant to the chief of the Signal Service, Abbe urged the Department of War to research weather conditions to provide a scientific basis behind the forecasts; he would continue to urge the study of meteorology as a science after becoming Weather Bureau chief. While a debate went on between the Signal Service and Congress over whether the forecasting of weather conditions should be handled by civilian agencies or the Signal Service's existing forecast office, a Congressional committee was formed to oversee the matter, recommending that the office's operations be transferred to the Department of War following a two-year investigation.[10]

The agency first became a civilian enterprise in 1890, when it became part of the Department of Agriculture. Under the oversight of that branch, the Bureau began issuing flood warnings and fire weather forecasts, and output the first daily national surface weather maps; it also established a network to distribute warnings for tropical cyclones as well as a data exchange service that relayed European weather analysis to the Bureau and vice versa.[11] The first Weather Bureau radiosonde was launched in Massachusetts in 1937, which prompted a switch from routine aircraft observation to radiosondes within two years. The Bureau prohibited the word "tornado" from being used in any of its weather products out of concern for inciting panic (a move contradicted in its intentions by the high death tolls in past tornado outbreaks due to the lack of advanced warning) until 1938, when it began disseminating tornado warnings exclusively to emergency management personnel.[12]

The Bureau would later be moved to the Department of Commerce in 1940.[13] On July 12, 1950, bureau chief Francis W. Reichelderfer officially lifted the agency's ban on public tornado alerts in a Circular Letter, noting to all first order stations that "Weather Bureau employees should avoid statements that can be interpreted as a negation of the Bureau's willingness or ability to make tornado forecasts", and that a "good probability of verification" exist when issuing such forecasts due to the difficulty in accurately predicting tornadic activity.[14] However it would not be until it faced criticism for continuing to refuse to provide public tornado warnings and preventing the release of the USAF Severe Weather Warning Center's tornado forecasts (pioneered in 1948 by Air Force Capt. Robert C. Miller and Major Ernest Fawbush) beyond military personnel that the Bureau issued its first experimental public tornado forecasts in March 1952.[12] In 1957, the Bureau began using radars for short-term forecasting of local storms and hydrological events, using modified versions of those used by Navy aircraft to create the WSR-57 (Weather Surveillance Radar, 1957), with a network of WSR systems being deployed nationwide through the early 1960s;[15] some of the radars were upgraded to WSR-74 models beginning in 1974.

The Weather Bureau became part of the Environmental Science Services Administration when that agency was formed in August 1966. The Environmental Science Services Administration was renamed the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) on October 1, 1970, with the enactment of the National Environmental Policy Act. At this time, the Weather Bureau became the National Weather Service.[8] NEXRAD (Next Generation Radar), a system of Doppler radars deployed to improve the detection and warning time of severe local storms, replaced the WSR-57 and WSR-74 systems between 1988 and 1997.[16][17] Bob Glahn has written a comprehensive history of the first hundred years of the National Weather Service.[18][19]

Forecast sub-organizations

The NWS, through a variety of sub-organizations, issues different forecast products to users, including the general public. Although, throughout history, text forecasts have been the means of product dissemination, the NWS has been using more forecast products of a digital, gridded, image or other modern format.[20] Each of the 122 Weather Forecast Offices (WFOs) send their graphical forecasts to a national server to be compiled in the National Digital Forecast Database (NDFD).[21] The NDFD is a collection of common weather observations used by organizations and the public, including precipitation amount, temperature, and cloud cover among other parameters. In addition to viewing gridded weather data via the internet, users can download and use the individual grids using a "GRIB2 decoder" which can output data as shapefiles, netCDF, GrADS, float files, and comma separated variable files.[22] Specific points in the digital database can be accessed using an XML SOAP service.

Fire weather

The National Weather Service issues many products relating to wildfires daily. For example, a Fire Weather Forecast, which have a forecast period covering up to seven days, is issued by local Weather Forecast Offices (WFOs) daily, with updates as needed. The forecasts contain weather information relevant to fire control and smoke management for the next 12 to 48 hours, such as wind direction and speed, and precipitation. The appropriate crews use this information to plan for staffing and equipment levels, the ability to conduct scheduled controlled burns, and assess the daily fire danger. Once per day, NWS meteorologists issue a coded fire weather forecast for specific United States Forestry Service observation sites that are then input into the National Fire Danger Rating System (NFDRS). This computer model outputs the daily fire danger that is then conveyed to the public in one of five ratings: low, moderate, high, very high, or extreme.[23]

The local Weather Forecast Offices of the NWS also, under a prescribed set of criteria, issue Fire Weather Watches and Red Flag Warnings as needed, in addition to issuing the daily fire weather forecasts for the local service area. These products alert the public and other agencies to conditions which create the potential for extreme fires. On the national level, the NWS Storm Prediction Center issues fire weather analyses for days one and two of the forecast period that provide supportive information to the local WFO forecasts regarding particular critical elements of fire weather conditions. These include large-scale areas that may experience critical fire weather conditions including the occurrence of "dry thunderstorms," which usually occur in the western U.S., and are not accompanied by any rain due to it evaporating before reaching the surface.[24]

State and federal forestry officials sometimes request a forecast from a WFO for a specific location called a "spot forecast," which are used to determine whether it will be safe to ignite a prescribed burn and how to situate crews during the controlling phase. Officials send in a request, usually during the early morning, containing the position coordinates of the proposed burn, the ignition time, and other pertinent information. The WFO composes a short-term fire weather forecast for the location and sends it back to the officials, usually within an hour of receiving the request.[24]

The NWS assists officials at the scene of large wildfires or other disasters, including HAZMAT incidents, by providing on-site support through Incident Meteorologists (IMET).[25] IMETs are NWS forecasters specially trained to work with Incident Management Teams during severe wildfire outbreaks or other disasters requiring on-site weather support. IMETs travel quickly to the incident site and then assemble a mobile weather center capable of providing continuous meteorological support for the duration of the incident. The kit includes a cell phone, a laptop computer, and communications equipment, used for gathering and displaying weather data such as satellite imagery or numerical forecast model output. Remote weather stations are also used to gather specific data for the point of interest,[25] and often receive direct support from the local WFO during such crises. IMETs, approximately 70 to 80 of which are employed nationally, can be deployed anywhere a disaster strikes and must be capable of working long hours for weeks at a time in remote locations under rough conditions.

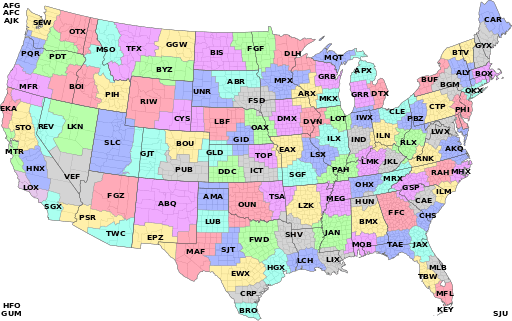

Weather Forecast Offices

The National Weather Service uses local branches, known as Weather Forecast Offices or WFOs, to issue products specific to those areas. Each WFO maintains a specific area of responsibility spanning multiple counties, parishes or other jurisdictions within the Continental United States – which, in some areas, cover multiple states – or individual possessions; the local offices handle responsibility of composing and disseminating forecast products and weather alerts to areas within their region of service. Some of the products that are only issued by the WFOs are severe thunderstorm and tornado warnings, flood, flash flood, and winter weather watches and warnings, some aviation products, and local forecast grids. The forecast products issued by a WFO are available on their individual pages within the Weather.gov website, which can be accessed through either forecast landing pages (which identify the office that disseminates the weather data) or via the alert map featured on the main page of the National Weather Service website.

National Centers for Environmental Prediction

Aviation

The NWS supports the aviation community through the production of several forecast products. Each area's WFO has responsibility for the issuance of Terminal Aerodrome Forecasts (TAFs) for airports in their jurisdiction.[26] TAFs are concise, coded 24-hour forecasts (30-hour forecasts for certain airports) for a specific airport, which are issued every six hours with amendments as needed. As opposed to a public weather forecast, a TAF only addresses weather elements critical to aviation; these include wind, visibility, cloud cover and wind shear.

Twenty-one NWS Center Weather Service Units (CWSU) are collocated with the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) Air Route Traffic Control Centers (ARTCC). Their main responsibility is to provide up-to-the-minute weather information and briefings to the Traffic Management Units and control room supervisors. Special emphasis is given to weather conditions that could be hazardous to aviation or impede the flow of air traffic in the National Airspace System. Beside scheduled and unscheduled briefings for decision-makers in the ARTCC and other FAA facilities, CWSU meteorologists also issue two unscheduled products. The Center Weather Advisory (CWA) is an aviation weather warning for thunderstorms, icing, turbulence, and low cloud ceilings and visibilities. The Meteorological Impact Statement (MIS) is a two- to 12-hour forecast that outlines weather conditions expected to impact ARTCC operations.[27]

The Aviation Weather Center (AWC), located in Kansas City, Missouri, is a central aviation support facility operated by the National Weather Service, which issues two primary products:

- AIRMET (Airmen's Meteorological Information) – Information on icing, turbulence, mountain obscuration, low-level wind shear, instrument meteorological conditions, and strong surface winds.

- SIGMETs (Significant Meteorological Information) – Issued for significant weather that may affect an airport of flight path in an area:

- Convective – Issued for an area of thunderstorms affecting an area of 3,000 square miles (7,800 km2) or greater, a line of thunderstorms at least 60 nmi (110 km) long, and/or severe or embedded thunderstorms affecting any area that are expected to last 30 minutes or longer.

- Non-convective – Issued for severe turbulence over a 3,000 square miles (7,800 km2) area, severe icing over a 3,000 square miles (7,800 km2), or instrument meteorological conditions over a 3,000 square miles (7,800 km2) area due to dust, sand, or volcanic ash.

Storm Prediction Center

The Storm Prediction Center (SPC) in Norman, Oklahoma issues severe thunderstorm and tornado watches in cooperation with local WFOs which are responsible for delineating jurisdictions affected by the issued watch, and SPC also issues mesoscale discussions focused upon possible convective activity. SPC compiles reports of severe hail, wind, or tornadoes issued by local WFOs each day when thunderstorms producing such phenomena occur in a given area, and formats the data into text and graphical products. It also provides forecasts on convective activity through day eight of the forecast period (most prominently, the threat of severe thunderstorms, the risk of which is assessed through a tiered system conveyed among six categories – general thunderstorms, marginal, slight, enhanced, moderate, or high – based mainly on the expected number of storm reports and regional coverage of thunderstorm activity over a given forecast day), and is responsible for issuing fire weather outlooks, which support local WFOs in the determination of the need for Red Flag Warnings.

Weather Prediction Center

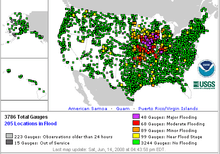

The Weather Prediction Center in College Park, Maryland provides guidance for future precipitation amounts and areas where excessive rainfall is likely,[28] while local NWS offices are responsible for issuing Flood Watches, Flash Flood Watches, Flood Warnings, Flash Flood Warnings, and Flood Advisories for their local County Warning Area, as well as the official rainfall forecast for areas within their warning area of responsibility. These products can and do emphasize different hydrologic issues depending on geographic area, land use, time of year, as well as other meteorological and non-meteorological factors (for example, during the early spring or late winter a Flood Warning can be issued for an ice jam that occurs on a river, while in the summer a Flood Warning will most likely be issued for excessive rainfall).

In recent years, the NWS has enhanced its dissemination of hydrologic information through the Advanced Hydrologic Prediction Service (AHPS).[29] The AHPS allows anyone to view near real-time observation and forecast data for rivers, lakes and streams. The service also enables the NWS to provide long-range probabilistic information which can be used for long-range planning decisions.

River Forecast Centers

Daily river forecasts are issued by the thirteen River Forecast Centers (RFCs) using hydrologic models based on rainfall, soil characteristics, precipitation forecasts, and several other variables. The first such center was founded on September 23, 1946.[30] Some RFCs, especially those in mountainous regions, also provide seasonal snow pack and peak flow forecasts. These forecasts are used by a wide range of users, including those in agriculture, hydroelectric dam operation, and water supply resources.

Ocean Prediction Center

The National Weather Service Ocean Prediction Center (OPC) in College Park, Maryland[31] issues marine products for areas that are within the national waters of the United States. NWS national centers or Weather Forecast Offices issue several marine products:

- Coastal Waters Forecast (CWF) – a text product issued by all coastal WFOs to explicitly state expected weather conditions within their marine forecast area of responsibility through day five; the product also addresses expected wave heights.

- Offshore Waters Forecast (OFF) – a text product issued by the OPC that provides forecast and warning information to mariners who travel on the oceanic waters adjacent to the U.S. coastal waters through day five.

- NAVTEX forecast – a text forecast issued by the OPC (combining data from the Coastal Waters and Offshore Waters Forecasts) designed to accommodate broadcast restrictions of U.S. Coast Guard NAVTEX transmitters.

- High Seas Forecast (HSF) – routine text product issued every six hours by OPC to provide warning and forecast information to mariners who travel on the oceanic waters.

National Hurricane Center

The National Hurricane Center (NHC) and the Central Pacific Hurricane Center (CPHC), respectively based in Miami, Florida and Honolulu, Hawaii, are responsible for monitoring tropical weather in the Atlantic, and central and eastern Pacific Oceans. In addition to releasing routine outlooks and discussions, the guidance center initiates advisories and discussions on individual tropical cyclones, as needed. If a tropical cyclone threatens the United States or its territories, individual WFOs begin issuing statements detailing the expected effects within their local area of responsibility. The NHC and CPHC issue products including tropical cyclone advisories, forecasts, and formation predictions, and warnings for the areas in the Atlantic and parts of the Pacific.

Climate Prediction Center

The Climate Prediction Center (CPC) in College Park, Maryland is responsible for all of the NWS's climate-related forecasts. Their mission is to "serve the public by assessing and forecasting the impacts of short-term climate variability, emphasizing enhanced risks of weather-related extreme events, for use in mitigating losses and maximizing economic gains." Their products cover time scales from a week to seasons, extending into the future as far as technically feasible, and cover the land, the ocean and the atmosphere, extending into the stratosphere. Most of the products issued by the center cover the Contiguous U.S. and Alaska.

Additionally, Weather Forecast Offices issue daily and monthly climate reports for official climate stations within their area of responsibility. These generally include recorded highs, lows and other information (including historical temperature extremes, fifty-year temperature and precipitation averages, and degree days). This information is considered preliminary until certified by the National Climatic Data Center.

Data acquisition

Surface observations

The primary network of surface weather observation stations in the United States is composed of Automated Surface Observing Systems (ASOS). The ASOS program is a joint effort of the National Weather Service (NWS), the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA), and the Department of Defense (DOD).[32] ASOS stations are designed to support weather forecast activities and aviation operations and, at the same time, support the needs of the meteorological, hydrological, and climatological research communities. ASOS was especially designed for the safety of the aviation community, therefore the sites are almost always located near airport runways. The system transmits routine hourly observations along with special observations when conditions exceed aviation weather thresholds (e.g. conditions change from visual meteorological conditions to instrument meteorological conditions). The basic weather elements observed are: sky condition, visibility, present weather, obstructions to vision, pressure, temperature, dew point, wind direction and speed, precipitation accumulation, and selected significant remarks. The coded observations are issued as METARs and look similar to this:

METAR KNXX 121155Z 03018G29KT 1/4SM +TSSN FG VV002 M05/M07 A2957 RMK PK WND 01029/1143 SLP026 SNINCR 2/10 RCRNR T2 SET 6///// 7//// 4/010 T10561067 11022 21056 55001 PWINO PNO FZRANO

Getting more information on the atmosphere, more frequently, and from more locations is the key to improving forecasts and warnings. Due to the large installation and operating costs associated with ASOS, the stations are widely spaced. Therefore, the Cooperative Observer Program (COOP), a network of approximately 11,000 mostly volunteer weather observers, provides much of the meteorological and climatological data to the country. The program, which was established in 1890 under the Organic Act, currently has a twofold mission:

- Provide observational meteorological data, usually consisting of daily maximum and minimum temperatures, snowfall, and 24-hour precipitation totals, required to define the climate of the United States and to help measure long-term climate changes.

- Provide observational meteorological data in near real-time to support forecast, warning and other public service programs of the NWS.

The National Weather Service also maintains connections with privately operated mesonets such as the Citizen Weather Observer Program for data collection, in part, through the Meteorological Assimilated Data Ingest System (MADIS). Funding is also provided to the CoCoRaHS volunteer weather observer network through parent agency NOAA.

Marine observations

NWS forecasters need frequent, high-quality marine observations to examine conditions for forecast preparation and to verify their forecasts after they are produced. These observations are especially critical to the output of numerical weather models because large bodies of water have a profound impact on the weather. Other users rely on the observations and forecasts for commercial and recreational activities. To help meet these needs, the NWS's National Data Buoy Center (NDBC) in Hancock County, Mississippi operates a network of about 90 buoys and 60 land-based coastal observing systems (C-MAN). The stations measure wind speed, direction, and gust; barometric pressure; and air temperature. In addition, all buoy and some C-MAN stations measure sea surface temperature, and wave height and period.[33] Conductivity and water current are measured at selected stations. All stations report on an hourly basis.

Supplemental weather observations are acquired through the United States Voluntary Observing Ship (VOS) program.[34] It is organized for the purpose of obtaining weather and oceanographic observations from transiting ships. An international program under World Meteorological Organization (WMO) marine auspices, the VOS has 49 countries as participants. The United States program is the largest in the world, with nearly 1,000 vessels. Observations are taken by deck officers, coded in a special format known as the "ships synoptic code", and transmitted in real-time to the NWS. They are then distributed on national and international circuits for use by meteorologists in weather forecasting, by oceanographers, ship routing services, fishermen, and many others. The observations are then forwarded for use by the National Climatic Data Center (NCDC) in Asheville, North Carolina.

Upper air observations

Upper air weather data is essential for weather forecasting and research. The NWS operates 92 radiosonde locations in North America and ten sites in the Caribbean. A small, expendable instrument package is suspended below a 2 metres (6.6 ft) wide balloon filled with hydrogen or helium, then released daily at or shortly after 1100 and 2300 UTC, respectively. As the radiosonde rises at about 300 meters/minute (1,000 ft/min), sensors on the radiosonde measure profiles of pressure, temperature, and relative humidity. These sensors are linked to a battery-powered radio transmitter that sends the sensor measurements to a ground receiver. By tracking the position of the radiosonde in flight, information on wind speed and direction aloft is also obtained. The flight can last longer than two hours, and during this time the radiosonde can ascend above 35 km (115,000 ft) and drift more than 200 km (120 mi) from the release point. When the balloon has expanded beyond its elastic limit and bursts (about 6 m or 20 ft in diameter), a small parachute slows the descent of the radiosonde, minimizing the danger to lives and property. Data obtained during the flights is coded and disseminated, at which point it can be plotted on a Skew-T or Stuve diagram for analysis. In recent years, the National Weather Service has begun incorporating data from AMDAR in its numerical models (however, the raw data is not available to the public).

Event-driven products

The National Weather Service has developed a multi-tier concept for forecasting or alerting the public to all types of hazardous weather:

- Outlook – Hazardous Weather Outlooks are issued daily by individual Weather Forecast Offices to address potentially hazardous weather or hydrologic events that may occur over the next seven days. The outlook will include information about the potential of convective thunderstorm activity (including the potential for severe thunderstorms), heavy rain or flooding, winter weather, and extremes of heat or cold. It is intended to provide information to those who need considerable lead time to prepare for the event, including notification to storm spotter groups and local emergency management agencies on the recommendation of activation during severe weather situations in areas prone to such events. Other outlooks are issued on an event-driven basis, such as the Flood Potential Outlook and Severe Weather Outlook.

- Advisory – An advisory is issued when a hazardous weather or hydrologic event is occurring, imminent, or likely. Advisories are for less serious conditions than warnings, that cause significant inconvenience and if caution is not exercised, could lead to situations that may threaten life or property.

- Watch – A watch is used when the risk of a hazardous weather or hydrologic event has increased significantly, but its occurrence, location or timing is still uncertain. It is intended to provide enough lead time so those who need to set their safety plans in motion can do so in advance if a forecasted event should occur. A watch means that hazardous weather is possible, but not imminent. People should have a plan of action in case a storm threatens and monitor various avenues that provide NOAA-disseminated data to listen for later information and possible warnings, especially when planning travel or outdoor activities.

- Warning – A warning is issued when a hazardous weather or hydrologic event is occurring, imminent or likely. A warning means weather conditions pose a threat to life or property. People in the path of the storm need to take protective action.

- Special Weather Statement(also Significant Weather Advisory) – A special weather statement is issued when something rare or unusual is occurring. These are usually triggered by sudden changes in meteorological conditions. The statements are to be taken as warnings for residents of a specific area. The warning generally states that an area might be at risk for a slight weather danger, though not all weather statements are warnings. Other times, statements describe informative facts about a weather system (such as local snowfall).

Product dissemination

NOAA Weather Radio All Hazards (NWR), promoted as "The Voice of the National Weather Service", is a special radio system that transmits weather forecasts and alerts 24 hours a day across most of the United States. The system – which is owned and operated by the NWS – consists of more than 1,000 transmitters, covering all 50 states; adjacent coastal waters; Puerto Rico; the U.S. Virgin Islands; and the U.S. Pacific Territories of American Samoa, Guam and the Northern Mariana Islands. NWR requires a special radio receiver or scanner capable of picking up the signal. Individual NWR stations broadcast any one of seven allocated frequencies centered on 162 MHz (known collectively as "weather band") in the VHF radio frequency band. In recent years, national emergency response agencies such as the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) and the Department of Homeland Security have begun to take advantage of NWR's ability to efficiently reach a large portion of the U.S. population. When necessary, the system can also be used (in conjunction with the Emergency Alert System) to broadcast civil, natural and technological emergency and disaster alerts and information, in addition to those related to weather – hence the addition of the phrasing "All Hazards" to the name.

The NOAA Weather Wire Service (NWWS) is a satellite data collection and dissemination system operated by the National Weather Service, which was established in October 2000. Its purpose is to provide state and federal government, commercial users, media and private citizens with timely delivery of meteorological, hydrological, climatological and geophysical information. All products in the NWWS data stream are prioritized, with weather and hydrologic warnings receiving the highest priority (watches are next in priority). NWWS delivers severe weather and storm warnings to users in ten seconds or less from the time of their issuance, making it the fastest delivery system available. Products are broadcast to users via the AMC-4 satellite.

The Emergency Managers Weather Information Network (EMWIN) is a system designed to provide the emergency management community with access to a set of NWS warnings, watches, forecasts and other products at no recurring cost. It can receive data via radio, internet, or a dedicated satellite dish, depending on the needs and capabilities of the user.

NOAAPORT is a one-way broadcast communication system which provides NOAA environmental data and information in near real-time to NOAA and external users. This broadcast service is implemented by a commercial provider of satellite communications utilizing C band.

The agency's online service, Weather.gov, is a data rich website operated by the NWS that serves as a portal to hundreds of thousands of webpages and more than 300 different NWS websites. Through its homepage, users can access local forecasts by entering a place name in the main forecast search bar, view a rapidly updated map of active watches and warnings, and select areas related to graphical forecasts, national maps, radar displays, river and air quality data, satellite images and climate information. Also offered are XML data feeds of active watches and warnings, ASOS observations and digital forecasts for 5x5 kilometer grids. All of NWS local weather forecast offices operate their own region-tailored web pages, which provide access to current products and other information specific to the office's local area of responsibility. Weather.gov superseded the Interactive Weather Information Network (IWIN), the agency's early internet service which provided NWS data from the 1990s through the mid-2000s.

Since 1983, the NWS has provided external user access to weather information obtained by or derived from the U.S. Government through a collection of data communication line services called the Family of Services (FOS), which is accessible via dedicated telecommunications access lines in the Washington, D.C., area. All FOS data services are driven by the NWS Telecommunication Gateway computer systems located at NWS headquarters in Silver Spring, Maryland. Users may obtain any of the individual services from NWS for a one-time connection charge and an annual user fee.

Technology

The WSR-88D Doppler weather radar system, also called NEXRAD, was developed by the National Weather Service during the mid-1980s, and fully deployed throughout the majority of the United States by 1997. There are 158 such radar sites in operation in the U.S., its various territorial possessions and selected overseas locations. This technology, because of its high resolution and ability to detect intra-cloud motions, is now the cornerstone of the agency's severe weather warning operations.

National Weather Service meteorologists use an advanced information processing, display and telecommunications system, the Advance Weather Interactive Processing System (AWIPS), to complete their work. These workstations allow them to easily view a multitude of weather and hydrologic information, as well as compose and disseminate products. The NWS Environmental Modeling Center was one of the early users of the ESMF common modeling infrastructure. The Global Forecast System (GFS) is one of the applications that is built on the framework.

In 2016, the NWS significantly increased the computational power of its supercomputers, spending $44 million on two new supercomputers from Cray and IBM. This was driven by relatively lower accuracy of NWS' Global Forecast System (GFS) numerical weather prediction model, compared to other global weather models.[35][36] This was most notable in the GFS model incorrectly predicting Hurricane Sandy turning out to sea until four days before landfall; while the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts' model predicted landfall correctly at seven days. The new supercomputers increased computational processing power from 776 teraflops to 5.78 petaflops.[37][38][39]

Organization

- National Weather Service (NWS)

- Chief Information Officer

- National Centers for Environmental Prediction (NCEP)

- Aviation Weather Center (AWC)

- Climate Prediction Center (CPC)

- Environmental Modeling Center (EMC)

- Weather Prediction Center (WPC)

- Ocean Prediction Center (OPC)

- NCEP Central Operations

- Space Weather Prediction Center (SWPC)

- Storm Prediction Center (SPC)

- National Hurricane Center (NHC)

- Hurricane Specialist Unit (HSU)

- Tropical Analysis and Forecast Branch (TAFB)

- Technical Support Branch (TSB)

- Chief Financial Officer

- Operational Systems

- Hydrologic Development

- Science and Technology

- Programs and Plans

- Meteorological Development Laboratory (MDL)

- Climate, Water and Weather Services

- 6 Regions (Eastern, Central, Southern, Western, Alaska & Pacific)

- 122 Weather Forecast Offices (WFOs)

- 21 Center Weather Service Units (CWSU)

- 13 River Forecast Centers (RFC)

- Pacific Tsunami Warning Center (PTWC)

- West Coast and Alaska Tsunami Warning Center (WCATWC)

- Spaceflight Meteorology Group (SMG)

Privatization and dismantling attempts

While respected as one of the premier weather organizations in the world, the National Weather Service has been perceived by some conservatives as competing unfairly with the private sector.[41] National Weather Service forecasts and data, being works of the federal government, are in the public domain and thus available to anyone for free in accordance with United States law. From time to time, the situation receives official review to ascertain if a leaner, more efficient approach may be had by some degree of privatization.

Aborted Byrne proposal

In 1983, under the administration of President Ronald Reagan, NOAA administrator John V. Byrne announced a proposal to sell all of the agency's weather satellite at auction with the intent to repurchase the weather data from private contractors that would acquire the satellites. Under the proposal, 30% of NOAA's workforce would be reviewed for potential layoffs, and certain specialty forecasts of agricultural and economic importance would be eliminated. NOAA also proposed outsourcing of weather observation stations, NOAA Weather Radio and computerized surface analysis to private companies. The proposal was met with negative reaction among the public, members of Congress and consumer advocacy groups (including most notably, Ralph Nader), objecting to the possibility of weather information intended for the public domain being sold to private entities that would profit from the sale of the data. The proposal to sell the satellite network failed in a Congressional vote, while other aspects of the proposal to dismantle portions of NOAA's agencies were eventually scuttled.[42]

Failed Santorum proposal

In 2005, Pennsylvania Senator Rick Santorum introduced the National Weather Service Duties Act of 2005,[43] a bill which would have prohibited the NWS from freely distributing weather data. The bill was widely criticized by users of the NWS's services, especially by emergency management officials who rely on the National Weather Service for information during situations such as fires, flooding, or severe weather. Groups such as the Aircraft Owners and Pilots Association condemned the bill's restrictions on weather forecasting as threatening the safety of air traffic, noting that 40% of all aviation accidents are at least partially weather-related.[44] The bill attracted no cosponsors, and died in committee during the 2005 Congressional session; no subsequent attempts have been made to restrict NWS forecasts.

See also

- List of National Weather Service locations

- Meteorological Service of Canada – a Canadian weather forecasting agency operated under Environment Canada, founded in 1876

- NOAA's Environmental Real-time Observation Network

- Radar Operations Center

- Reginald Fessenden – known for proving the practicality of using a network of coastal radio stations to transmit weather information

References

- ↑ "History of the National Weather Service". National Weather Service. Retrieved 2 July 2016.

- ↑ "Guide to Federal Records: Records of the Weather Bureau". National Archives and Records Administration. Retrieved May 23, 2014.

- ↑ "About NOAA's National Weather Service".

- ↑ "FY 2017 Budget Summary" (pdf). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. 2016. p. 53.

- ↑ "Silver Spring CDP, Maryland". U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved August 2, 2009.

- ↑ "NOAA's National Weather Service". National Weather Service. Retrieved August 2, 2009.

- ↑ Sharyl J. Nass; Bruce Stillman. Large-scale Biomedical Science. National Academies Press. p. 224. ISBN 978-0-309-08912-8.

- 1 2 "NWS History". National Weather Service. Retrieved September 20, 2011.

- ↑ Marlene Bradford (2001). Scanning the Skies: A History of Tornado Forecasting. University of Oklahoma Press. p. 34. ISBN 978-0-8061-3302-7.

- ↑ Nancy Mathis (2007). Storm Warning: The Story of a Killer Tornado. Touchstone. pp. 46–50. ISBN 978-0-7432-8053-2.

- ↑ Nancy Mathis (2007). Storm Warning: The Story of a Killer Tornado. Touchstone. p. 51. ISBN 978-0-7432-8053-2.

- 1 2 Nancy Mathis (2007). Storm Warning: The Story of a Killer Tornado. Touchstone. pp. 47–53. ISBN 978-0-7432-8053-2.

- ↑ United States National Research Council (1995). Aviation Weather Services: A Call For Federal Leadership and Action. National Academies Press. p. 18. ISBN 978-0-309-05380-8.

- ↑ Roger Edwards. "The Online Tornado FAQ". Storm Prediction Center. Retrieved July 6, 2009.

- ↑ Nancy Mathis (2007). Storm Warning: The Story of a Killer Tornado. Touchstone. p. 86. ISBN 978-0-7432-8053-2.

- ↑ Timothy D. Crum; Ron L. Alberty (1993). "The WSR-88D and the WSR-88D Operational Support Facility". Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. 74: 74.9. Bibcode:1993BAMS...74.1669C. doi:10.1175/1520-0477(1993)074<1669:twatwo>2.0.co;2.

- ↑ Nancy Mathis (2007). Storm Warning: The Story of a Killer Tornado. Touchstone. pp. 92–94. ISBN 978-0-7432-8053-2.

- ↑ "File:The United States Weather Service, First 100 years by Bob Glahn part 1.pdf - Wikimedia Commons" (PDF). Wikimedia Commons. Retrieved September 6, 2013.

- ↑ "File:The United States Weather Service, First 100 years by Bob Glahn part 2.pdf - Wikimedia Commons" (PDF). Wikimedia Commons. Retrieved September 6, 2013.

- ↑ "NWS Strategic Plan PDF Overview" (PDF). NWS Strategic Plan - 2011. National Weather Service. Retrieved December 11, 2012.

- ↑ "NDFD Home Page". National Digital Forecast Database. National Weather Service. November 8, 2008. Retrieved December 19, 2008.

- ↑ "NDFD Database Contents". National Digital Forecast Database. National Weather Service. Retrieved December 11, 2012.

- ↑ "National Fire Danger Rating System". NWS Western Region Headquarters. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

- 1 2 "SPC and its Products". Storm Prediction Center. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved February 22, 2013.

- 1 2 "NWS Flagstaff". NWS Western Region Headquarters. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved February 22, 2013.

- ↑ "AWC - Aviation Weather Center". National Weather Service. Retrieved December 11, 2012.

- ↑ "AWC - Center Weather Service Unit Products (CWA, MIS)". Aviation Weather Center. National Weather Service. Retrieved December 11, 2012.

- ↑ "About the HPC". Hydrometeorological Prediction Center. Retrieved September 3, 2008.

- ↑ "About AHPS". National Weather Service. Retrieved December 19, 2008.

- ↑ "History of OHRFC". National Weather Service. Retrieved February 26, 2012.

- ↑ "Ocean Prediction Center". National Centers for Environmental Prediction. National Weather Service. Retrieved December 15, 2012.

- ↑ "NWS ASOS Program". National Weather Service. Retrieved December 19, 2008.

- ↑ "Moored Buoy Program". National Data Buoy Center. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. February 4, 2008. Retrieved January 29, 2011.

- ↑ "The WMO Voluntary Observing Ships (VOS) Scheme". National Data Buoy Center. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. January 28, 2009. Retrieved March 18, 2011.

- ↑ Berger, Eric (21 June 2016). "The US weather model is now the fourth best in the world". Ars Technica.

- ↑ Berger, Eric (11 March 2016). "The European forecast model already kicking America's butt just improved". Ars Technica. Retrieved 16 August 2016.

- ↑ Kravets, David (5 January 2015). "National Weather Service will boost its supercomputing capacity tenfold". Ars Technica. Retrieved 16 August 2016.

- ↑ Rice, Doyle (22 February 2016). "Supercomputer quietly puts U.S. weather resources back on top". USA Today. Retrieved 16 August 2016.

- ↑ "NOAA completes weather and climate supercomputer upgrades". NOAA. Retrieved 16 August 2016.

- ↑ Kevin Moran (May 23, 2005). "Emergency center now ready to weather storm / The high-tech facility is built higher, stronger". Houston Chronicle. Hearst Corporation. Retrieved January 2, 2010.

- ↑ J. Gratz. "Taking the Initiative: Public/Private Weather Debate Continues…". University of Colorado.

- ↑ Nancy Mathis (2007). Storm Warning: The Story of a Killer Tornado. Touchstone. pp. 90–91. ISBN 978-0-7432-8053-2.

- ↑ "S.786 -- National Weather Services Duties Act of 2005". Library of Congress.

- ↑ "Air Traffic Services Brief -- National Weather Service Duties Act of 2005 -- Santorum Bill S. 786". Aircraft Owners and Pilots Association. April 28, 2005.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to National Weather Service. |

- Official website

- National Weather Service on Twitter

- National Weather Service Employees Organization (NWSEO)