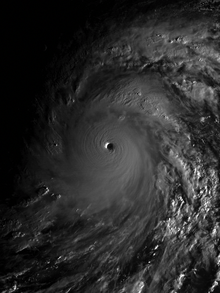

Typhoons in the Philippines

In the Philippines, tropical cyclones (typhoons) are called bagyo.[1] Tropical cyclones entering the Philippine Area of Responsibility are given a local name by the Philippine Atmospheric, Geophysical and Astronomical Services Administration (PAGASA), which also raises public storm signal warnings as deemed necessary.[2][3] Around 19 tropical cyclones or storms enter the Philippine Area of Responsibility in a typical year and of these usually 6 to 9 make landfall.[4][5]

The deadliest overall tropical cyclone to impact the Philippines is believed to have been the Haiphong typhoon which is estimated to have killed up to 20,000 people as it passed over the country in September 1881. In modern meteorological records, the deadliest storm was Typhoon Haiyan/Yolanda, which became the strongest landfalling tropical cyclone ever recorded as it crossed the Central Philippines on November 7–8, 2013. The wettest known tropical cyclone to impact the archipelago was the July 14–18, 1911 cyclone which dropped over 2,210 millimetres (87 in) of rainfall within a 3-day, 15-hour period in Baguio City.[6] Tropical cyclones usually account for at least 30 percent of the annual rainfall in the northern Philippines while being responsible for less than 10 percent of the annual rainfall in the southern islands.

The Philippines is the most-exposed large country in the world to tropical cyclones; the cyclones have even affected settlement patterns in the northern islands: for example, the eastern coast of Luzon is very sparsely populated.

Etymology and naming conventions

It is said that the term bagyo, a Filipino word meaning typhoon arose after a 1911 storm in the city of Baguio had a record rainfall of 46 inches within a 24-hour period.[1][7][8]

However, this theory is impossible because the Vocabulario de la Lengua Tagala first published in 1754 contains an entry for "BAG-YO" which translates it as "Tempestad, uracan" (tempest, hurricane), proof that the term "bagyo" already existed in Tagalog in the 1700s. The reverse entry for "Huracan" translates it into Tagalog as "Baguio, Bag-yo".

Names of storms

Since the middle of the 20th Century, American forecasters have named tropical storms after people, originally using only female names.[9] Philippine forecasters from the now-PAGASA started assigning Filipino names to storms in 1963 following the American practice, using names of people in alphabetical order, from A to Z.[9] Beginning in January 2000, the World Meteorological Organization"s Typhoon Committee began assigning names to storms nominated by the 14 Asian countries who are members with each country getting 2 to 3 a year.[9] These names, unlike the American and Filipino traditions, are not names for people exclusively but include flowers, animals, food, etc. and they are not in alphabetical order by name but rather in alphabetical order by the country that nominated the name.[9] After January 2000, Filipino forecasters continued their tradition of naming storms that enter the Philippines Area of Responsibility and so there are often two names for each storm, the PAGASA name and the so-called "international name".

| Category | Sustained winds |

|---|---|

| Super Typhoon | ≥119 knots ≥220 km/h |

| Typhoon | 64–119 knots 118–220 km/h |

| Severe Tropical Storm | 48–63 knots 89–117 km/h |

| Tropical Storm | 34–47 knots 62–88 km/h |

| Tropical Depression | ≤33 knots ≤61 km/h |

Variability in activity

On an annual time scale, activity reaches a minimum in May, before increasing steadily through June, and spiking from July through September, with August being the most active month for tropical cyclones in the Philippines. Activity falls off significantly in October.[10] The most active season, since 1945, for tropical cyclone strikes on the island archipelago was 1993 when nineteen tropical cyclones moved through the country (though there were 36 storms that were named by PAGASA).[11] There was only one tropical cyclone which moved through the Philippines in 1958.[12] The most frequently impacted areas of the Philippines by tropical cyclones are northern Luzon and eastern Visayas.[13] A ten-year average of satellite determined precipitation showed that at least 30 percent of the annual rainfall in the northern Philippines could be traced to tropical cyclones, while the southern islands receive less than 10 percent of their annual rainfall from tropical cyclones.[14]

Tropical Cyclone Warning Signals

| Signal #1 winds of 30–60 km/h (20-37 mph) are expected to occur within 36 hours |

| Signal #2 winds of 61–120 km/h (38–73 mph) are expected to occur within 24 hours |

| Signal #3 winds of 121–170 km/h, (74–105 mph) are expected to occur within 18 hours. |

| Signal #4 winds of 171–220 km/h, (106–137 mph) are expected to occur within 12 hours. |

| Signal #5 winds of at least 220 km/h, (137 mph) are expected to occur within 12 hours. |

The Philippine Atmospheric, Geophysical and Astronomical Services Administration (PAGASA) releases tropical cyclone warnings in the form of Tropical Cyclone Warning Signals.[3] An area having a storm signal may be under:

- TCWS #1 - Tropical cyclone winds of 30 km/h (19 mph) to 60 km/h (37 mph) are expected within the next 36 hours. (Note: If a tropical cyclone forms very close to the area, then a shorter lead time is seen on the warning bulletin.)

- TCWS #2 - Tropical cyclone winds of 61 km/h (38 mph) to 120 km/h (75 mph) are expected within the next 24 hours.

- TCWS #3 - Tropical cyclone winds of 121 km/h (75 mph) to 170 km/h (110 mph) are expected within the next 18 hours.

- TCWS #4 - Tropical cyclone winds of 171 km/h (106 mph) to 220 km/h (140 mph) are expected within 12 hours.

- TCWS #5 - Tropical cyclone winds greater than 220 km/h (140 mph) are expected within 12 hours.

These Tropical Cyclone Warning Signals are usually raised when an area (in the Philippines only) is about to be hit by a tropical cyclone. As a tropical cyclone gains strength and/or gets nearer to an area having a storm signal, the warning may be upgraded to a higher one in that particular area (e.g. a signal No. 1 warning for an area may be increased to signal #3). Conversely, as a tropical cyclone weakens and/or gets farther to an area, it may be downgraded to a lower signal or may be lifted (that is, an area will have no storm signal).

Classes for Preschool are canceled when Signal No. 1 is in effect. Elementary and High School classes and below are cancelled under Signal No. 2 and classes for Colleges and Universities and below are cancelled under Signal Nos. 3, 4 and 5.

Deadliest Cyclones

| Rank[15] | Storm | Dates of impact | Deaths |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Haiphong 1881 | 1881, September 27 | 20,000 |

| 2 | Haiyan/Yolanda 2013 | 2013, November 7–8 | 6,300[16] |

| 3 | Thelma/Uring 1991 | 1991, November 4–7 | 5,101[17] |

| 4 | Bopha/Pablo 2012 | 2012, December 2–9 | 1,901 |

| 5 | Angela Typhoon | 1867, September 22 | 1,800[18] |

| 6 | Winnie 2004 | 2004, November 27–29 | 1,593 |

| 7 | October 1897 Typhoon | 1897, October 7 | 1,500[18] |

| 8 | Ike/Nitang 1984 | 1984, September 3–6 | 1,492 |

| 9 | Fengshen/Frank 2008 | 2008, June 20–23 | 1,410 |

| 10 | Durian/Reming 2006 | 2006, November 29-December 1 | 1,399 |

Most destructive

|

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | Name | Year | PHP | USD |

| 1 | Haiyan (Yolanda) | 2013 | 89.6 billion | 2.02 billion |

| 2 | Bopha (Pablo) | 2012 | 42.2 billion | 1.04 billion |

| 3 | Rammasun (Glenda) | 2014 | 38.6 billion | 871 million |

| 4 | Parma (Pepeng) | 2009 | 27.3 billion | 608 million |

| 5 | Nesat (Pedring) | 2011 | 15 billion | 333 million |

| 6 | Fengshen (Frank) | 2008 | 13.5 billion | 301 million |

| 7 | Megi (Juan) | 2010 | 11 billion | 255 million |

| 8 | Ketsana (Ondoy) | 2009 | 11 billion | 244 million |

| 9 | Mike (Ruping) | 1990 | 10.8 billion | 241 million |

| 10 | Angela (Rosing) | 1995 | 10.8 billion | 241 million |

|

| ||||

|

Sources

| ||||

Wettest recorded tropical cyclones

| Precipitation | Storm | Location | Ref. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | mm | in | |||

| 1 | 2210.0 | 87.01 | July 1911 cyclone | Baguio City | [19] |

| 2 | 1854.3 | 73.00 | Parma (Pepeng) 2009 | Baguio City | [20] |

| 3 | 1216.0 | 47.86 | Carla (Trining) 1967 | Baguio City | [19] |

| 4 | 1116.0 | 43.94 | Zeb (Iliang) 1998 | La Trinidad, Benguet | [21] |

| 5 | 1085.8 | 42.74 | Utor (Feria) 2001 | Baguio City | [22] |

| 6 | 1077.8 | 42.43 | Koppu (Lando) 2015 | Baguio City | [20] |

| 7 | 1012.7 | 39.87 | Mindulle (Igme) 2004 | [23] | |

| 8 | 902.0 | 35.51 | Kujira (Dante) 2009 | [24] | |

| 9 | 879.9 | 34.64 | September 1929 typhoon | Virac, Catanduanes | [25] |

| 10 | 869.6 | 34.24 | Dinah (Openg) 1977 | Western Luzon | [26] |

See also

- 2015 Pacific typhoon season

- 2016 Pacific typhoon season

- List of Pacific typhoon seasons (1939 onwards)

- List of retired Philippine typhoon names

For other storms impacting the Philippines in deadly seasons, see:

- Effects of the 2009 Pacific typhoon season in the Philippines

- Effects of the 2013 Pacific typhoon season in the Philippines

References

- 1 2 Glossary of Meteorology. Baguio. Retrieved on 2008-06-11.

- ↑ Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory, Hurricane Research Division. "Frequently Asked Questions: What are the upcoming tropical cyclone names?". NOAA. Retrieved 2006-12-11.

- 1 2 Republic of the Philippines. Department of Science and Technology. Philippine Atmospheric, Geophysical and Astronomical Services Administration. (n.d.). The Modified Philippine Public Storm Warning Signals. Retrieved November 6, 2016.

- ↑ Joint Typhoon Warning Center. Appendix B: Characteristics of Tropical Cyclones Affecting the Philippine Islands (Shoemaker 1991). Retrieved on 2008-04-20.

- ↑ Philippine Atmospheric, Geophysical and Astronomical Services Administration (PAGASA). (January 2009). "Member Report to the ESCAP/WMO Typhoon Committee, 41st Session" (PDF). Retrieved 2009-12-17.

- ↑ J. L. H. Paulhaus (1973). World Meteorological Organization Operational Hydrology Report No. 1: Manual For Estimation of Probable Maximum Precipitation. World Meteorological Organization. p. 178.

- ↑ English, Fr. Leo James (2004), Tagalog-English Dictionary, 19th printing, Manila: Congregation of the Most Holy Redeemer, p. 117, ISBN 971-08-4357-5

- ↑ Philippine Center for Language Study; Jean Donald Bowen (1965), Jean Donald Bowen, ed., Beginning Tagalog: a course for speakers of English (10 ed.), University of California Press, p. 349, ISBN 978-0-520-00156-5

- 1 2 3 4 "Names". Typhoon2000.com. David Michael V. Padua. Retrieved 9 November 2013.

- ↑ Ricardo García-Herrera, Pedro Ribera, Emiliano Hernández and Luis Gimeno (2003-09-26). "Typhoons in the Philippine Islands, 1566-1900" (PDF). David V. Padua. p. 40. Retrieved 2010-04-13.

- ↑ Joint Typhoon Warning Center (2009). "Member Report Republic of the Philippines" (PDF). Philippine Atmospheric, Geophysical and Astronomical Services Administration. World Meteorological Organization. Retrieved 2010-04-14.

- ↑ Joint Typhoon Warning Center (1959). "1958". United States Navy.

- ↑ Colleen A. Sexton (2006). Philippines in Pictures. Twenty-First Century Books. ISBN 978-0-8225-2677-3. Retrieved 2008-11-01.

- ↑ Edward B. Rodgers; Robert F. Adler & Harold F. Pierce. "Satellite-measured rainfall across the Pacific Ocean and tropical cyclone contribution to the total". Retrieved 2008-11-25.

- ↑ Ten Worst Typhoons of the Philippines (A Summary)

- ↑ "TyphoonHaiyan - RW Updates". United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs. December 28, 2013. Philippines: Hundreds of corpses unburied after Philippine typhoon. Retrieved December 30, 2013.

- ↑ Leoncio A. Amadore, PhD Socio-Economic Impacts of Extreme Climatic Events in the Philippines. Retrieved on 2007-02-25.

- 1 2 Pedro Ribera; Ricardo Garcia-Herrera & Luis Gimeno (July 2008). "Historical deadly typhoons in the Philippines". Weather. Royal Meteorological Society. 63 (7): 196. Bibcode:2008Wthr...63..194R. doi:10.1002/wea.275.

- 1 2 J. L. H. Paulhaus (1973). World Meteorological Organization Operational Hydrology Report No. 1: Manual For Estimation of Probable Maximum Precipitation. World Meteorological Organization. p. 178.

- 1 2 Nick Wiltgen (October 21, 2015). "Former Super Typhoon Koppu (Lando) Weakens to Remnant Low over Northern Philippines". The Weather Channel. Retrieved October 21, 2015.

- ↑ Guillermo Q. Tabios III; David S. Rojas Jr. Rainfall Duration-Frequency Curve for Ungaged Sites in the High Rainfall, Benguet Mountain Region in the Philippines (PDF) (Report). Kyoto University. Retrieved 2015-06-02.

- ↑ Leoncio A. Amadore, Ph.D. Socio-Economic Impacts of Extreme Climatic Events in the Philippines. Retrieved on 2007-02-25.

- ↑ Padgett, Gary; Kevin Boyle; John Wallace; Huang Chunliang; Simon Clarke (2006-10-26). "Monthly Global Tropical Cyclone Summary June 2004". Australian Severe Weather Index. Jimmy Deguara. Retrieved 2007-01-13.

- ↑ Steve Lang (May 7, 2009). "Hurricane Season 2009: Kujira (Western Pacific Ocean)". NASA. Retrieved December 23, 2011.

- ↑ Coronas, José (September 1929). "Typhoons and Depressions – a Destructive Typhoon Over Southern and Central Luzon on September 2 and 3, 1929" (PDF). Monthly Weather Review. American Meteorological Society. Weather Bureau. 57 (9): 398–399. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1929)57<398b:TADDTO>2.0.CO;2. Retrieved September 26, 2015.

- ↑ Narciso O. Itoralba (December 1981). Annual Tropical Cyclone Report 1977. Philippine Atmospheric, Geophysical and Astronomical Services Administration. p. 65.

External links

- Philippine Tropical Cyclone Update

- Typhoon2000

- Monthly typhoon tracks: 1951-2010

- Typhoon Haiyan coverage by CBSnews

- CRS International relief organization quickly mobilizes to help Philippine Typhoon victims