Two-phase locking

In databases and transaction processing, two-phase locking (2PL) is a concurrency control method that guarantees serializability.[1][2] It is also the name of the resulting set of database transaction schedules (histories). The protocol utilizes locks, applied by a transaction to data, which may block (interpreted as signals to stop) other transactions from accessing the same data during the transaction's life.

By the 2PL protocol locks are applied and removed in two phases:

- Expanding phase: locks are acquired and no locks are released.

- Shrinking phase: locks are released and no locks are acquired.

Two types of locks are utilized by the basic protocol: Shared and Exclusive locks. Refinements of the basic protocol may utilize more lock types. Using locks that block processes, 2PL may be subject to deadlocks that result from the mutual blocking of two or more transactions.

Data-access locks

A lock is a system object associated with a shared resource such as a data item of an elementary type, a row in a database, or a page of memory. In a database, a lock on a database object (a data-access lock) may need to be acquired by a transaction before accessing the object. Correct use of locks prevents undesired, incorrect or inconsistent operations on shared resources by other concurrent transactions. When a database object with an existing lock acquired by one transaction needs to be accessed by another transaction, the existing lock for the object and the type of the intended access are checked by the system. If the existing lock type does not allow this specific attempted concurrent access type, the transaction attempting access is blocked (according to a predefined agreement/scheme). In practice a lock on an object does not directly block a transaction's operation upon the object, but rather blocks that transaction from acquiring another lock on the same object, needed to be held/owned by the transaction before performing this operation. Thus, with a locking mechanism, needed operation blocking is controlled by a proper lock blocking scheme, which indicates which lock type blocks which lock type.

Two major types of locks are utilized:

- Write-lock (exclusive lock) is associated with a database object by a transaction (Terminology: "the transaction locks the object," or "acquires lock for it") before writing (inserting/modifying/deleting) this object.

- Read-lock (shared lock) is associated with a database object by a transaction before reading (retrieving the state of) this object.

The common interactions between these lock types are defined by blocking behavior as follows:

- An existing write-lock on a database object blocks an intended write upon the same object (already requested/issued) by another transaction by blocking a respective write-lock from being acquired by the other transaction. The second write-lock will be acquired and the requested write of the object will take place (materialize) after the existing write-lock is released.

- A write-lock blocks an intended (already requested/issued) read by another transaction by blocking the respective read-lock .

- A read-lock blocks an intended write by another transaction by blocking the respective write-lock .

- A read-lock does not block an intended read by another transaction. The respective read-lock for the intended read is acquired (shared with the previous read) immediately after the intended read is requested, and then the intended read itself takes place.

Several variations and refinements of these major lock types exist, with respective variations of blocking behavior. If a first lock blocks another lock, the two locks are called incompatible; otherwise the locks are compatible. Often lock types blocking interactions are presented in the technical literature by a Lock compatibility table. The following is an example with the common, major lock types:

Lock compatibility table Lock type read-lock write-lock read-lock X write-lock X X - X indicates incompatibility, i.e, a case when a lock of the first type (in left column) on an object blocks a lock of the second type (in top row) from being acquired on the same object (by another transaction). An object typically has a queue of waiting requested (by transactions) operations with respective locks. The first blocked lock for operation in the queue is acquired as soon as the existing blocking lock is removed from the object, and then its respective operation is executed. If a lock for operation in the queue is not blocked by any existing lock (existence of multiple compatible locks on a same object is possible concurrently) it is acquired immediately.

- Comment: In some publications the table entries are simply marked "compatible" or "incompatible", or respectively "yes" or "no".

Two-phase locking and its special cases

Two-phase locking

According to the two-phase locking protocol, a transaction handles its locks in two distinct, consecutive phases during the transaction's execution:

- Expanding phase (aka Growing phase): locks are acquired and no locks are released (the number of locks can only increase).

- Shrinking phase: locks are released and no locks are acquired.

The two phase locking rule can be summarized as: never acquire a lock after a lock has been released. The serializability property is guaranteed for a schedule with transactions that obey this rule.

Typically, without explicit knowledge in a transaction on end of phase-1, it is safely determined only when a transaction has completed processing and requested commit. In this case all the locks can be released at once (phase-2).

Strict two-phase locking

To comply with the S2PL protocol a transaction needs to comply with 2PL, and release its write (exclusive) locks only after it has ended, i.e., being either committed or aborted. On the other hand, read (shared) locks are released regularly during phase 2. This protocol is not appropriate in B-trees because it causes Bottleneck (while B-trees always starts searching from the parent root).

Strong strict two-phase locking

or Rigorousness, or Rigorous scheduling, or Rigorous two-phase locking

To comply with strong strict two-phase locking (SS2PL) the locking protocol releases both write (exclusive) and read (shared) locks applied by a transaction only after the transaction has ended, i.e., only after both completing executing (being ready) and becoming either committed or aborted. This protocol also complies with the S2PL rules. A transaction obeying SS2PL can be viewed as having phase-1 that lasts the transaction's entire execution duration, and no phase-2 (or a degenerate phase-2). Thus, only one phase is actually left, and "two-phase" in the name seems to be still utilized due to the historical development of the concept from 2PL, and 2PL being a super-class. The SS2PL property of a schedule is also called Rigorousness. It is also the name of the class of schedules having this property, and an SS2PL schedule is also called a "rigorous schedule". The term "Rigorousness" is free of the unnecessary legacy of "two-phase," as well as being independent of any (locking) mechanism (in principle other blocking mechanisms can be utilized). The property's respective locking mechanism is sometimes referred to as Rigorous 2PL.

SS2PL is a special case of S2PL, i.e., the SS2PL class of schedules is a proper subclass of S2PL (every SS2PL schedule is also an S2PL schedule, but S2PL schedules exist that are not SS2PL).

SS2PL has been the concurrency control protocol of choice for most database systems and utilized since their early days in the 1970s. It is proven to be an effective mechanism in many situations, and provides besides Serializability also Strictness (a special case of cascadeless Recoverability), which is instrumental for efficient database recovery, and also Commitment ordering (CO) for participating in distributed environments where a CO based distributed serializability and global serializability solutions are employed. Being a subset of CO, an efficient implementation of distributed SS2PL exists without a distributed lock manager (DLM), while distributed deadlocks (see below) are resolved automatically. The fact that SS2PL employed in multi database systems ensures global serializability has been known for years before the discovery of CO, but only with CO came the understanding of the role of an atomic commitment protocol in maintaining global serializability, as well as the observation of automatic distributed deadlock resolution (see a detailed example of Distributed SS2PL). As a matter of fact, SS2PL inheriting properties of Recoverability and CO is more significant than being a subset of 2PL, which by itself in its general form, besides comprising a simple serializability mechanism (however serializability is also implied by CO), in not known to provide SS2PL with any other significant qualities. 2PL in its general form, as well as when combined with Strictness, i.e., Strict 2PL (S2PL), are not known to be utilized in practice. The popular SS2PL does not require marking "end of phase-1" as 2PL and S2PL do, and thus is simpler to implement. Also, unlike the general 2PL, SS2PL provides, as mentioned above, the useful Strictness and Commitment ordering properties.

Many variants of SS2PL exist that utilize various lock types with various semantics in different situations, including cases of lock-type change during a transaction. Notable are variants that use Multiple granularity locking.

Comments:

- SS2PL Vs. S2PL: Both provide Serializability and Strictness. Since S2PL is a super class of SS2PL it may, in principle, provide more concurrency. However, no concurrency advantage is typically practically noticed (exactly same locking exists for both, with practically not much earlier lock release for S2PL), and the overhead of dealing with an end-of-phase-1 mechanism in S2PL, separate from transaction-end, is not justified. Also, while SS2PL provides Commitment ordering, S2PL does not. This explains the preference of SS2PL over S2PL.

- Especially before 1990, but also after, in many articles and books, e.g., (Bernstein et al. 1987, p. 59),[1] the term "Strict 2PL" (S2PL) has been frequently defined by the locking protocol "Release all locks only after transaction end," which is the protocol of SS2PL. Thus, "Strict 2PL" could not be there the name of the intersection of Strictness and 2PL, which is larger than the class generated by the SS2PL protocol. This has caused confusion. With an explicit definition of S2PL as the intersection of Strictness and 2PL, a new name for SS2PL, and an explicit distinction between the classes S2PL and SS2PL, the articles (Breitbart et al. 1991)[3] and (Raz 1992)[4] have intended to clear the confusion: The first using the name "Rigorousness," and the second "SS2PL."

- A more general property than SS2PL exists (a schedule super-class), Strict commitment ordering (Strict CO, or SCO), which as well provides both serializability, strictness, and CO, and has similar locking overhead. Unlike SS2PL, SCO does not block upon a read-write conflict (a read-lock does not block acquiring a write-lock; both SCO and SS2PL have the same behavior for write-read and write-write conflicts) at the cost of a possible delayed commit, and upon such conflict type SCO has shorter average transaction completion time and better performance than SS2PL.[5] While SS2PL obeys the lock compatibility table above, SCO has the following table:

Lock compatibility for SCO Lock type read-lock write-lock read-lock write-lock X X - Note that though SCO releases all locks at transaction end and complies with the 2PL locking rules, SCO is not a subset of 2PL because of its different lock compatibility table. SCO allows materialized read-write conflicts between two transactions in their phases 1, which 2PL does not allow in phase-1 (see about materialized conflicts in Serializability). On the other hand 2PL allows other materialized conflict types in phase-2 that SCO does not allow at all. Together this implies that the schedule classes 2PL and SCO are incomparable (i.e., no class contains the other class).

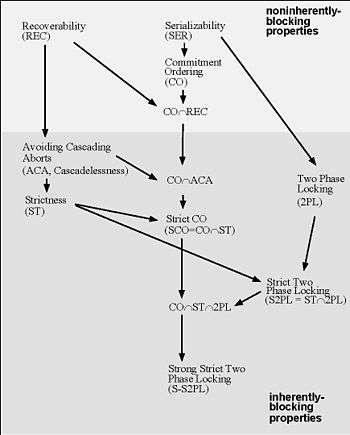

Summary - Relationships among classes

Between any two schedule classes (define by their schedules' respective properties) that have common schedules, either one contains the other (strictly contains if they are not equal), or they are incomparable. The containment relationships among the 2PL classes and other major schedule classes are summarized in the following diagram. 2PL and its subclasses are inherently blocking, which means that no optimistic implementations for them exist (and whenever "Optimistic 2PL" is mentioned it refers to a different mechanism with a class that includes also schedules not in the 2PL class).

Deadlocks in 2PL

Locks block data-access operations. Mutual blocking between transactions results in a deadlock, where execution of these transactions is stalled, and no completion can be reached. Thus deadlocks need to be resolved to complete these transactions' executions and release related computing resources. A deadlock is a reflection of a potential cycle in the precedence graph, that would occur without the blocking. A deadlock is resolved by aborting a transaction involved with such potential cycle, and breaking the cycle. It is often detected using a wait-for graph (a graph of conflicts blocked by locks from being materialized; conflicts not materialized in the database due to blocked operations are not reflected in the precedence graph and do not affect serializability), which indicates which transaction is "waiting for" lock release by which transaction, and a cycle means a deadlock. Aborting one transaction per cycle is sufficient to break the cycle. If a transaction has been aborted due to deadlock resolution, it is up to the application to decide what to do next. Usually, an application will restart the transaction from the beginning but may delay this action to give other transactions sufficient time to finish in order to avoid causing another deadlock.[6]

In a distributed environment an atomic commitment protocol, typically the Two-phase commit (2PC) protocol, is utilized for atomicity. When recoverable data (data under transaction control) partitioned among 2PC participants (i.e., each data object is controlled by a single 2PC participant), then distributed (global) deadlocks, deadlocks involving two or more participants in 2PC, are resolved automatically as follows:

When SS2PL is effectively utilized in a distributed environment, then global deadlocks due to locking generate voting-deadlocks in 2PC, and are resolved automatically by 2PC (see Commitment ordering (CO), in Exact characterization of voting-deadlocks by global cycles; No reference except the CO articles is known to notice this). For the general case of 2PL, global deadlocks are similarly resolved automatically by the synchronization point protocol of phase-1 end in a distributed transaction (synchronization point is achieved by "voting" (notifying local phase-1 end), and being propagated to the participants in a distributed transaction the same way as a decision point in atomic commitment; in analogy to decision point in CO, a conflicting operation in 2PL cannot happen before phase-1 end synchronization point, with the same resulting voting-deadlock in the case of a global data-access deadlock; the voting-deadlock (which is also a locking based global deadlock) is automatically resolved by the protocol aborting some transaction involved, with a missing vote, typically using a timeout).

Comment:

- When data are partitioned among the atomic commitment protocol (e.g., 2PC) participants, automatic global deadlock resolution has been overlooked in the database research literature, though deadlocks in such systems has been a quite intensive research area:

- For CO and its special case SS2PL, the automatic resolution by the atomic commitment protocol has been noticed only in the CO articles. However, it has been noticed in practice that in many cases global deadlocks are very infrequently detected by the dedicated resolution mechanisms, less than could be expected ("Why do we see so few global deadlocks?"). The reason is probably the deadlocks that are automatically resolved and thus not handled and uncounted by the mechanisms;

- For 2PL in general, the automatic resolution by the (mandatory) end-of-phase-one synchronization point protocol (which has same voting mechanism as atomic commitment protocol, and same missing vote handling upon voting deadlock, resulting in global deadlock resolution) has not been mentioned until today (2009). Practically only the special case SS2PL is utilized, where no end-of-phase-one synchronization is needed in addition to atomic commit protocol.

- In a distributed environment where recoverable data are not partitioned among atomic commitment protocol participants, no such automatic resolution exists, and distributed deadlocks need to be resolved by dedicated techniques.

See also

References

- 1 2 Philip A. Bernstein, Vassos Hadzilacos, Nathan Goodman (1987): Concurrency Control and Recovery in Database Systems, Addison Wesley Publishing Company, ISBN 0-201-10715-5

- ↑ Gerhard Weikum, Gottfried Vossen (2001): Transactional Information Systems, Elsevier, ISBN 1-55860-508-8

- ↑ Yuri Breitbart, Dimitrios Georgakopoulos, Marek Rusinkiewicz, Abraham Silberschatz (1991): "On Rigorous Transaction Scheduling", IEEE Transactions on Software Engineering (TSE), September 1991, Volume 17, Issue 9, pp. 954-960, ISSN 0098-5589

- ↑ Yoav Raz (1992): "The Principle of Commitment Ordering, or Guaranteeing Serializability in a Heterogeneous Environment of Multiple Autonomous Resource Managers Using Atomic Commitment" (PDF), Proceedings of the Eighteenth International Conference on Very Large Data Bases (VLDB), pp. 292-312, Vancouver, Canada, August 1992, ISBN 1-55860-151-1 (also DEC-TR 841, Digital Equipment Corporation, November 1990)

- ↑ Yoav Raz (1991): "Locking Based Strict Commitment Ordering, or How to improve Concurrency in Locking Based Resource Managers", DEC-TR 844, December 1991.

- ↑ Principles of transaction processing; ISBN 9780080948416; Chapter 6 Page 152