Paladin

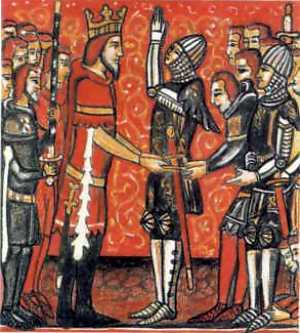

The Paladins, sometimes known as the Twelve Peers, were the foremost warriors of Charlemagne's court, according to the literary cycle known as the Matter of France.[1] They first appear in the early chansons de geste such as The Song of Roland, where they represent Christian valour against the Saracen hordes inside Europe.

The paladins and their associated exploits are largely later fictional inventions, with some basis in historical Frankish retainers of the 8th century and events such as the Battle of Roncevaux Pass in 778 and the confrontation of the Frankish Empire with Umayyad Al-Andalus in the Marca Hispanica.

Etymology

The earliest recorded instance of the word paladin in the English language dates to 1592, in Delia (Sonnet XLVI) by Samuel Daniel.[1] It entered English through the Middle French word paladin, which itself derived from the Latin palatinus.[1] All these words for Charlemagne's Twelve Peers descend ultimately from the Latin palatinus, most likely through the Old French palatin.[1]

The Latin palatinus referred to an official of the Roman Emperor connected to the imperial palace on the Palatine Hill. Over time this word came to refer to other high-level officials in the imperial, majestic and royal courts.[2] The word palatine, used in various European countries in the medieval and modern eras, has the same derivation.[2]

By the 13th century words referring specifically to Charlemagne's peers began appearing in European languages; the earliest is the Italian paladino.[1] Modern French has paladin, Spanish has paladín or paladino (reflecting alternate derivations from the French and Italian), while German has Paladin.[1] By extension "paladin" has come to refer to any chivalrous hero such as King Arthur's Knights of the Round Table.[1]

Paladin was also used to refer to the leaders of armies supporting the Protestant Frederick V in the Thirty Years War ending in 1648.[3]

History

In their earliest appearances the paladins were not the companions of Charlemagne, but of his vassal Roland. This Roland is based on the historical figure Hruodland mentioned by Charlemagne's biographer Einhard as a Lord of the Breton March who died in the Battle of Roncevaux Pass in 778. Nothing else is known of him.[4] By the end of the 12th century the paladins were increasingly thought of as an association reporting to the king after the fashion of the Round Table; the earliest romance to portray them in this way is Fierabras, dating to around 1170.

The names of the twelve paladins vary from romance to romance, and often more than twelve are named. The number is popular because it resembles the Twelve Apostles giving the king the position of Jesus as a reminder of his holy mission as ruler. All Carolingian paladin stories feature paladins named Roland and Oliver; other recurring characters are Archbishop Turpin, Ogier the Dane, Huon of Bordeaux, Fierabras, Renaud de Montauban and Ganelon. Tales of the paladins once rivaled the stories of King Arthur and the knights of the Round Table in popularity.

The paladins figure into many chansons de geste and other tales associated with Charlemagne. In the above-mentioned Fierabras, they retrieve holy relics stolen from Rome by the Saracen giant Fierabras and (in some versions) convert him to Christianity and recruit him to their ranks. In Le Pèlerinage de Charlemagne they accompany their king on a pilgrimage to Jerusalem and Constantinople in order to outdo the Byzantine Emperor Hugo.

The Song of Roland (11th-12th century)

Their greatest moments come in The Song of Roland, which depicts their defense of Charlemagne's army against the Saracens of Al-Andalus, and their deaths at the Battle of Roncevaux Pass due to the treachery of Ganelon. The Song of Roland lists the twelve paladins as Roland, Charlemagne's nephew and the chief hero among the paladins; Oliver, Roland's friend and strongest ally; and Gérin, Gérier (these two are killed in the same laisse [123] by the same Saracen, Grandonie), Bérengier, Otton, Samson, Engelier, Ivon, Ivoire, Anséis, Girard (similar spellings are possible).[5] Other characters elsewhere considered part of the twelve appear in the song, such as Archbishop Turpin and Ogier the Dane.

Boiardo and Ariosto (16th century)

The Italian Renaissance authors Matteo Maria Boiardo and Ludovico Ariosto, whose works were once as widely read and respected as William Shakespeare's, contributed prominently to the literary and poetical reworking of the tales of the epic deeds of the paladins. Their works, Orlando Innamorato and Orlando Furioso, send the paladins on even more fantastic adventures than their predecessors. They list the paladins quite differently, but keep the number at twelve.[6]

Boiardo and Ariosto's paladins are Orlando (Roland), Charlemagne's nephew and the chief hero among the paladins; Oliver, the rival to Roland; Ferumbras (Fierabras), the Saracen who became a Christian; Astolpho, descended from Charles Martel and cousin to Orlando; Ogier the Dane; Ganelon the betrayer, who appears in Dante Alighieri's Inferno;[7] Rinaldo (Renaud de Montauban); Malagigi (Maugris), a sorcerer; Florismart, a friend to Orlando; Guy de Bourgogne; Namo (Naimon or Namus), Duke of Bavaria, Charlemagne's trusted adviser; and Otuel, another converted Saracen.

The Italian Orlandos inspired a number of composers over the next few centuries, who created operas and other musical works on Orlando and the paladins. Afterwards the Charlemagne material went into decline. While the Arthurian legend experienced a major revival in the 19th century in the hands of the Romantic and Victorian poets, writers, and artists, ensuring that Arthur and his knights are well known into the 21st century, no such resurgence occurred for Charlemagne and his paladins. Modern adaptations and reworkings including the Carolingian paladins are few and far between, but the concept of the chivalrous "paladin" lives on.

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "Paladin". From the Oxford English Dictionary. Retrieved November 23, 2008.

- 1 2 "Palatine". From the Oxford English Dictionary. Retrieved November 23, 2008.

- ↑ Wilson, Peter H. The Thirty Years War: Europe's Tragedy, Harvard University Press, 2009

- ↑ Dutton, Paul Edward, ed. and trans. Charlemagne's Courtier: The Complete Einhard, pp. 21–22. Peterborough, Ontario, Canada: Broadview Press, 1998.

- ↑ Conradus the priest (12th century), Song of Roland. ISBN 3-920153-02-2

- ↑ Frank, Grace, "La Passion du Palatinus: mystère du XIVe siècle," in Les Classiques français du moyen âge (30) Paris 1922.

- ↑ The Divine Comedy, Canto XXXII.

External links

The dictionary definition of paladin at Wiktionary

The dictionary definition of paladin at Wiktionary