Tujeon

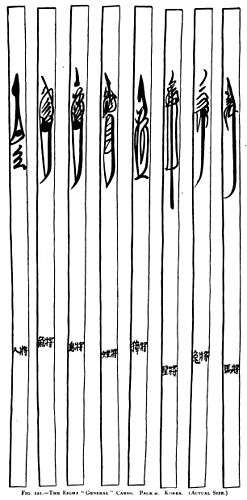

Tujeon (Hangul: 투전; Hanja: 鬪牋; RR: tujeon; MR: t'ujŏn; literally meaning fighting tablets) were the traditional playing cards of Korea.[1] Decks typically contained twenty-five, forty, sixty or eighty cards: nine numeral cards, and one General (jang), to each suit.[1][2] The suits and their generals are as follows:[3][4]

- Man (Hangul: 사람; RR: saram; MR: saram) led by the King

- Fish (Hangul: 물고기; RR: mulgogi; MR: mulgogi) led by the Dragon

- Crow (Hangul: 까마귀; RR: ggamagwi; MR: kkamagwi) led by the Phoenix

- Pheasant (Hangul: 꿩; RR: ggyeong; MR: kkwŏng) led by the Falcon

- Roe deer (Hangul: 노루; RR: noru; MR: noru) led by the Tiger

- Star (Hangul: 별; RR: byeol; MR: pyŏl) led by the North Star

- Rabbit (Hangul: 토끼; RR: toggi; MR: t'okki) led by the Eagle

- Horse (Hangul: 말; RR: mal; MR: mal) led by the Wagon

The physical cards are very long and narrow, typically measuring about 8 inches (200 mm) tall and 0.5 inches (13 mm) across.[5] They are made of oiled paper, leather or silk.[1][5] The backs are usually decorated with a stylized feather design.[6]

History

In his 1895 book Korean Games, with notes on the corresponding games of China and Japan, ethnographer Stewart Culin suggested that tujeon originated from the similarly-shaped symbolic bamboo "arrows" used for divination in sixth-century Korea.[1][5] This hypothesis, however, is supported mainly by visual similarity,[5] and remains unsubstantiated.[1]

Writing from the early 19th century, Yi Gyugyeong (1788-1856) claimed that Jang Hyeon (b. 1613) brought the Chinese card game of Madiao back to Korea.[4] Yi also claimed Jang simplified the cards to create tujeon while in prison and taught the game to prisoners and guards. Jang himself is believed to have died in prison. King Jeongjo (r. 1776-1800) issued several ineffective bans against tujeon after gambling was causing serious social problems.

By the early 19th century, tujeon evolved somewhat from its original form: decks were typically only forty to sixty cards in size, using four or six of the eight suits; and the numeral cards were no longer marked to distinguish their suit, being used interchangeably. Only the generals kept their suits.[6] The cards were replaced by hanafuda during the Japanese occupation but some tujeon rules were transferred over to the Japanese cards.[7][8][9]

Games

By far the most popular game was gabo japgi, so much so that the name was used interchangeably with tujeon.[10] Also known as yeot bang mangyi (엿방망이, "sweetmeat pestle"), it is a baccarat-like game related to the Chinese domino game kol-ye-si (골여시).[3][11] It is played with the 60 card deck and the object is to reach gabo or kapo which is gambling slang for 9. The game seems to be derived from Kabufuda games where the goal is to reach kabu or kaho which is also slang for 9. Both kabu and kapo are possibly descended from the Portuguese cavo which was slang for a stake or wager.[12] Another similar game is Komi, played with Ganjifa cards, from Odisha, India along Portugal's old trade routes.[13] Baccarat did not appear in Europe until mid-19th century France and was preceded by a simpler game called Macao, further hinting at a Portuguese connection.[14] Another possible point of origin is China, where the games of Pai Gow (dominoes) and Che zhang (cards) also have the target of reaching 9 but they are also more complicated and award bonuses for certain combinations.[15][16]

Another popular game was dong dang (동당), an early rummy game similar to Khanhoo.[3]

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Htou-tjyen. |

- 1 2 3 4 5 Simon Wintle. "Playing Cards in Korea". The World of Playing Cards. Retrieved November 13, 2012.

- ↑ James Edward Whitney, jr. (2003). "Playing Cards: Guide". Harvard University Library Online Archival Search Information System. Harvard College. Retrieved November 14, 2012.

- 1 2 3 Culin, Stewart (1895). Korean Games, with notes on the corresponding games of China and Japan. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania. pp. 123–126. Retrieved November 13, 2012.

- 1 2 Yi, I-Hwa (2006). Korea's Pastimes and Customs: A Social History (1st American ed.). Hong Kong: Hangilsa Publishing Co. p. 29.

- 1 2 3 4 Schwartz, David G. (2006). Roll the Bones: the History of Gambling. New York: Gotham Books. pp. 41–42. ISBN 1-59240-208-9.

- 1 2 Culin, Stewart (1896). Chess and Playing Cards. Atlanta, Georgia: University of Pennsylvania. pp. 918–919. Retrieved November 13, 2012.

- ↑ Mann, Sylvia (1990). All Cards on the Table. Leinfelden: Deutsches Spielkarten-Museum. p. 200.

- ↑ Fairbairn, John (1991). "Modern Korean Cards - A Japanese Perspective". The Playing-Card. 20 (2): 76–80.

- ↑ Sutda (archived) at hana.kirisame.org. Retrieved 13 November 2016.

- ↑ Mann, Sylvia (1990). All Cards on the Table. Leinfelden: Deutsches Spielkarten-Museum. p. 335.

- ↑ Kol-Ye-Si rules at domino-play. Retrieved 5 November 2015.

- ↑ Fairbairn, John (1986). "A Card Game Played with Kurofuda". The Playing-Card. 15 (1): 27.

- ↑ Hopewell, Jeff (2006). "Komi and Nakash". The Playing-Card. 34 (1): 67.

- ↑ Parlett, David. "Related face count games". Historic Card Games. Retrieved 1 August 2015.

- ↑ Lo, Andrew (2003). "Pan Zhiheng's 'Xu Yezi Pu' (Sequel to a Manual of Leaves) - Part 2". The Playing-Card. 31 (6): 278–281.

- ↑ McLeod, John (2004). "Playing the Game: Partition games". The Playing-Card. 32 (4): 173–175.