Sum of angles of a triangle

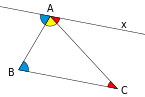

In several geometries, a triangle has three vertices and three sides, where three angles of a triangle are formed at each vertex by a pair of adjacent sides. In a Euclidean space, the sum of measures of these three angles of any triangle is invariably equal to the straight angle, also expressed as 180°, π radians, two right angles, or a half-turn.

It was unknown for a long time whether other geometries exist, where this sum is different. The influence of this problem on mathematics was particularly strong during the 19th century. Ultimately, the answer was proven to be positive: in other spaces (geometries) this sum can be greater or lesser, but it then must depend on the triangle. Its difference from 180° is a case of angular defect and serves as an important distinction for geometric systems.

Cases

Euclidean geometry

In Euclidean geometry, the triangle postulate states that the sum of the angles of a triangle is two right angles. This postulate is equivalent to the parallel postulate.[1] In the presence of the other axioms of Euclidean geometry, the following statements are equivalent:[2]

- Triangle postulate: The sum of the angles of a triangle is two right angles.

- Playfair's axiom: Given a straight line and a point not on the line, exactly one straight line may be drawn through the point parallel to the given line.

- Proclus' axiom: If a line intersects one of two parallel lines, it must intersect the other also.[3]

- Equidistance postulate: Parallel lines are everywhere equidistant (i.e. the distance from each point on one line to the other line is always the same.)

- Triangle area property: The area of a triangle can be as large as we please.

- Three points property: Three points either lie on a line or lie on a circle.

- Pythagoras' theorem: In a right-angled triangle, the square of the hypotenuse equals the sum of the squares of the other two sides.[1]

Hyperbolic geometry

The sum of the angles of a hyperbolic triangle is less than 180°. The relation between angular defect and the triangle's area was first proven by Johann Heinrich Lambert.[4]

One can easily see how hyperbolic geometry breaks Playfair's axiom, Proclus' axiom (the parallelism, defined as non-intersection, is intransitive in an hyperbolic plane), the equidistance postulate (the points on one side of, and equidistant from, a given line do not form a line), and Pythagoras' theorem. A circle[5] cannot have arbitrarily small curvature,[6] so the three points property also fails.

The sum of the angles can be arbitrarily small (but positive). For an ideal triangle, a generalization of hyperbolic triangles, this sum is equal to zero.

Spherical geometry

For a spherical triangle, the sum of the angles is greater than 180° and can be up to 540°. Specifically, the sum of the angles is

- 180° × (1 + 4f ),

where f is the fraction of the sphere's area which is enclosed by the triangle.

Note that spherical geometry does not satisfy several of Euclid's axioms (including the parallel postulate.)

Exterior angles

Angles between adjacent sides of a triangle are referred to as interior angles in Euclidean and other geometries. Exterior angles can be also defined, and the Euclidean triangle postulate can be formulated as the exterior angle theorem. One can also consider the sum of all three exterior angles, that equals to 360°[7] in the Euclidean case (as for any convex polygon), is less than 360° in the spherical case, and is greater than 360° in the hyperbolic case.

In differential geometry

In the differential geometry of surfaces, the question of a triangle's angular defect is understood as a special case of the Gauss–Bonnet theorem where the curvature of a closed curve is not a function, but a measure with the support in exactly three points – vertices of a triangle.

References

- 1 2 Eric W. Weisstein (2003). CRC concise encyclopedia of mathematics (2nd ed.). p. 2147. ISBN 1-58488-347-2.

The parallel postulate is equivalent to the Equidistance postulate, Playfair axiom, Proclus axiom, the Triangle postulate and the Pythagorean theorem.

- ↑ Keith J. Devlin (2000). The Language of Mathematics: Making the Invisible Visible. Macmillan. p. 161. ISBN 0-8050-7254-3.

- ↑ Essentially, the transitivity of parallelism.

- ↑ Ratcliffe, John (2006), Foundations of Hyperbolic Manifolds, Graduate Texts in Mathematics, 149, Springer, p. 99, ISBN 9780387331973,

That the area of a hyperbolic triangle is proportional to its angle defect first appeared in Lambert's monograph Theorie der Parallellinien, which was published posthumously in 1786.

- ↑ Defined as the set of points at the fixed distance from its centre.

- ↑ Defined in the differentially-geometrical sense.

- ↑ From the definition of an exterior angle, its sums up to the straight angle with the interior angles. So, the sum of three exterior angles added to the sum of three interior angles always gives three straight angles.

See also

- Euclid's Elements

- Foundations of geometry

- Hilbert's axioms

- Saccheri quadrilateral (considered earlier than Saccheri by Omar Khayyám)

- Lambert quadrilateral