Bible translations

| Part of a series on |

| Translation |

|---|

| Types |

| Theory |

| Technologies |

| Localization |

| Institutional |

|

| Related topics |

|

The Bible has been translated into many languages from the biblical languages of Hebrew, Aramaic and Greek. As of September 2016 the full Bible has been translated into 554 languages, and 2,932 languages have at least some portion of the Bible.[1]

The Latin Vulgate was dominant in Western Christianity through the Middle Ages. Since then, the Bible has been translated into many more languages. English Bible translations also have a rich and varied history of more than a millennium.

Original text

Hebrew Bible

The Tanakh was mainly written in Biblical Hebrew, with some portions (notably in Daniel and Ezra) in Biblical Aramaic. From the 6th century to the 10th century, Jewish scholars, today known as Masoretes, compared the text of all known biblical manuscripts in an effort to create a unified, standardized text. A series of highly similar texts eventually emerged, and any of these texts are known as Masoretic Texts (MT). The Masoretes also added vowel points (called niqqud) to the text, since the original text only contained consonant letters. This sometimes required the selection of an interpretation, since some words differ only in their vowels—their meaning can vary in accordance with the vowels chosen. In antiquity, variant Hebrew readings existed, some of which have survived in the Samaritan Pentateuch and other ancient fragments, as well as being attested in ancient versions in other languages.[2]

New Testament

The New Testament was written in Koine Greek.[3]

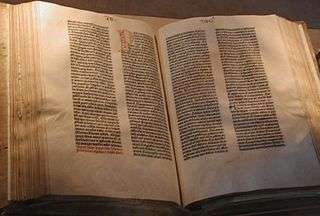

The discovery of older manuscripts, which belong to the Alexandrian text-type, including the 4th century Codex Vaticanus and Codex Sinaiticus, led scholars to revise their view about the original Greek text. Attempts to reconstruct the original text are called critical editions. Karl Lachmann based his critical edition of 1831 on manuscripts dating from the 4th century and earlier, to argue that the Textus Receptus must be corrected according to these earlier texts. However, there are some who believe that it has not been proven that these older manuscripts are in fact more reliable than the Textus Receptus.

The autographs, the Greek manuscripts written by the original authors, have not survived. Scholars surmise the original Greek text from the versions that do survive. The three main textual traditions of the Greek New Testament are sometimes called the Alexandrian text-type (generally minimalist), the Byzantine text-type (generally maximalist), and the Western text-type (occasionally wild). Together they comprise most of the ancient manuscripts.

Most variants among the manuscripts are minor, such as alternative spelling, alternative word order, the presence or absence of an optional definite article ("the"), and so on. Occasionally, a major variant happens when a portion of a text was missing. Examples of major variants are the endings of Mark, the Pericope Adulteræ, the Comma Johanneum, and the Western version of Acts.

Early manuscripts of the letters of Paul and other New Testament writings show no punctuation whatsoever.[4][5] The punctuation was added later by other editors, according to their own understanding of the text.

History of Bible translations

Ancient translations of the Hebrew Bible

Aramaic Targums

Some of the first translations of the Jewish Torah began during the first exile in Babylonia, when Aramaic became the lingua franca of the Jews. With most people speaking only Aramaic and not understanding Hebrew, the Targums were created to allow the common person to understand the Torah as it was read in ancient synagogues.

Greek Septuagint

By the 3rd century BC, Alexandria had become the center of Hellenistic Judaism, and during the 3rd to 2nd centuries BC translators compiled in Egypt a Koine Greek version of the Hebrew scriptures in several stages (completing the task by 132 BC). The Talmud ascribes the translation effort to Ptolemy II Philadelphus (r. 285-246 BC), who allegedly hired 72 Jewish scholars for the purpose, for which reason the translation is commonly known as the Septuagint, (from the Latin septuaginta, "seventy"), a name which it gained in "the time of Augustine of Hippo" (354–430 AD).[6] The Septuagint (LXX), the very first translation of the Hebrew Bible into Greek, later became the accepted text of the Old Testament in the Christian church and the basis of its canon. Jerome based his Latin Vulgate translation on the Hebrew for those books of the Bible preserved in the Jewish canon (as reflected in the Masoretic text), and on the Greek text for the deuterocanonical books.

In his City of God 18.42, while repeating the story of Aristeas with typical embellishments, Augustine adds the remark, "It is their translation that it has now become traditional to call the Septuagint" ...[Latin omitted]... Augustine thus indicates that this name for the Greek translation of the scriptures was a relatively recent development. However, he offers no clue as to which of the possible antecedents led to this development:[7] and was widely used by Greek-speaking Jews, and later by Christians.[8] It differs somewhat from the later standardized Hebrew (Masoretic Text). This translation was promoted by way of a legend (primarily recorded as the Letter of Aristeas) that seventy (or in some sources, seventy-two) separate translators all produced identical texts; supposedly proving its accuracy.[9]

Versions of the Septuagint contain several passages and whole books not included in the Masoretic texts of the Tanakh. In some cases these additions were originally composed in Greek, while in other cases they are translations of Hebrew books or of Hebrew variants not present in the Masoretic texts. Recent discoveries have shown that more of the Septuagint additions have a Hebrew origin than previously thought. While there are no complete surviving manuscripts of the Hebrew texts on which the Septuagint was based, many scholars believe that they represent a different textual tradition ("Vorlage") from the one that became the basis for the Masoretic texts.[2]

Early translations in Late Antiquity

Origen's Hexapla placed side by side six versions of the Old Testament, including the 2nd century Greek translations of Aquila of Sinope and Symmachus the Ebionite. His eclectic recension of the Septuagint had a significant influence on the Old Testament text in several important manuscripts. The canonical Christian Bible was formally established by Bishop Cyril of Jerusalem in 350 (although it had been generally accepted by the church previously), confirmed by the Council of Laodicea in 363 (both lacked the book of Revelation), and later established by Athanasius of Alexandria in 367 (with Revelation added), and Jerome's Vulgate Latin translation dates to between AD 382 and 420. Latin translations predating Jerome are collectively known as Vetus Latina texts.

Christian translations also tend to be based upon the Hebrew, though some denominations prefer the Septuagint (or may cite variant readings from both). Bible translations incorporating modern textual criticism usually begin with the masoretic text, but also take into account possible variants from all available ancient versions. The received text of the Christian New Testament is in Koine Greek,[lower-alpha 1] and nearly all translations are based upon the Greek text.

Jerome began by revising the earlier Latin translations, but ended by going back to the original Greek, bypassing all translations, and going back to the original Hebrew wherever he could instead of the Septuagint.

The New Testament was translated into Gothic in the 4th century by Ulfilas. In the 5th century, Saint Mesrob translated the Bible using the Armenian alphabet invented by him. Also dating from the same period are the Syriac, Coptic, Old Nubian, Ethiopic and Georgian translations.

There are also several ancient translations, most important of which are in the Syriac dialect of Aramaic (including the Peshitta and the Diatessaron gospel harmony), in the Ethiopian language of Ge'ez, and in Latin (both the Vetus Latina and the Vulgate).

In 331, the Emperor Constantine commissioned Eusebius to deliver fifty Bibles for the Church of Constantinople. Athanasius (Apol. Const. 4) recorded Alexandrian scribes around 340 preparing Bibles for Constans. Little else is known, though there is plenty of speculation. For example, it is speculated that this may have provided motivation for canon lists, and that Codex Vaticanus Graecus 1209, Codex Sinaiticus and Codex Alexandrinus are examples of these Bibles. Together with the Peshitta, these are the earliest extant Christian Bibles.[10]

Middle Ages

When ancient scribes copied earlier books, they wrote notes on the margins of the page (marginal glosses) to correct their text—especially if a scribe accidentally omitted a word or line—and to comment about the text. When later scribes were copying the copy, they were sometimes uncertain if a note was intended to be included as part of the text. See textual criticism. Over time, different regions evolved different versions, each with its own assemblage of omissions and additions.

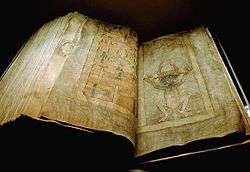

The earliest surviving complete manuscript of the entire Bible in Latin is the Codex Amiatinus, a Latin Vulgate edition produced in 8th century England at the double monastery of Wearmouth-Jarrow.

During the Middle Ages, translation, particularly of the Old Testament was discouraged. Nevertheless, there are some fragmentary Old English Bible translations, notably a lost translation of the Gospel of John into Old English by the Venerable Bede, which he is said to have prepared shortly before his death around the year 735. An Old High German version of the gospel of Matthew dates to 748. Charlemagne in ca. 800 charged Alcuin with a revision of the Latin Vulgate. The translation into Old Church Slavonic was started in 863 by Cyril and Methodius.

Alfred the Great had a number of passages of the Bible circulated in the vernacular in around 900. These included passages from the Ten Commandments and the Pentateuch, which he prefixed to a code of laws he promulgated around this time. In approximately 990, a full and freestanding version of the four Gospels in idiomatic Old English appeared, in the West Saxon dialect; these are called the Wessex Gospels.

Pope Innocent III in 1199 banned unauthorized versions of the Bible as a reaction to the Cathar and Waldensian heresies. The synods of Toulouse and Tarragona (1234) outlawed possession of such renderings. There is evidence of some vernacular translations being permitted while others were being scrutinized.

The complete Bible was translated into Old French in the late 13th century. Parts of this translation were included in editions of the popular Bible historiale, and there is no evidence of this translation being suppressed by the Church.[11] The entire Bible was translated into Czech around 1360.

The most notable Middle English Bible translation, Wycliffe's Bible (1383), based on the Vulgate, was banned by the Oxford Synod in 1408. A Hungarian Hussite Bible appeared in the mid 15th century, and in 1478, a Catalan translation in the dialect of Valencia. Many parts of the Bible were printed by William Caxton in his translation of the Golden Legend, and in Speculum Vitae Christi (The Mirror of the Blessed Life of Jesus Christ).

Reformation and Early Modern period

The earliest printed edition of the Greek New Testament appeared in 1516 from the Froben press, by Desiderius Erasmus, who reconstructed its Greek text from several recent manuscripts of the Byzantine text-type. He occasionally added a Greek translation of the Latin Vulgate for parts that did not exist in the Greek manuscripts. He produced four later editions of this text. Erasmus was Roman Catholic, but his preference for the Byzantine Greek manuscripts rather than the Latin Vulgate led some church authorities to view him with suspicion.

In 1521, Martin Luther was placed under the Ban of the Empire, and he retired to the Wartburg Castle. During his time there, he translated the New Testament from Greek into German. It was printed in September 1522. The first complete Dutch Bible, partly based on the existing portions of Luther's translation, was printed in Antwerp in 1526 by Jacob van Liesvelt.[12]

The first printed edition with critical apparatus (noting variant readings among the manuscripts) was produced by the printer Robert Estienne of Paris in 1550. The Greek text of this edition and of those of Erasmus became known as the Textus Receptus (Latin for "received text"), a name given to it in the Elzevier edition of 1633, which termed it as the text nunc ab omnibus receptum ("now received by all").

- The use of numbered chapters and verses was not introduced until the Middle Ages and later. The system used in English was developed by Stephanus (Robert Estienne of Paris) (see Chapters and verses of the Bible)

Later critical editions incorporate ongoing scholarly research, including discoveries of Greek papyrus fragments from near Alexandria, Egypt, that date in some cases within a few decades of the original New Testament writings.[13] Today, most critical editions of the Greek New Testament, such as UBS4 and NA27, consider the Alexandrian text-type corrected by papyri, to be the Greek text that is closest to the original autographs. Their apparatus includes the result of votes among scholars, ranging from certain {A} to doubtful {E}, on which variants best preserve the original Greek text of the New Testament.

Critical editions that rely primarily on the Alexandrian text-type inform nearly all modern translations (and revisions of older translations). For reasons of tradition, however, some translators prefer to use the Textus Receptus for the Greek text, or use the Majority Text which is similar to it but is a critical edition that relies on earlier manuscripts of the Byzantine text-type. Among these, some argue that the Byzantine tradition contains scribal additions, but these later interpolations preserve the orthodox interpretations of the biblical text—as part of the ongoing Christian experience—and in this sense are authoritative. Distrust of the textual basis of modern translations has contributed to the King-James-Only Movement.

The churches of the Protestant Reformation translated the Greek of the Textus Receptus to produce vernacular Bibles, such as the German Luther Bible (1522), the Polish Brest Bible (1563), the Spanish "Biblia del Oso" (in English: Bible of the Bear, 1569) which later became the Reina-Valera Bible upon its first revision in 1602, the Czech Melantrich Bible (1549) and Bible of Kralice (1579-1593) and numerous English translations of the Bible. Tyndale's New Testament translation (1526, revised in 1534, 1535 and 1536) and his translation of the Pentateuch (1530, 1534) and the Book of Jonah were met with heavy sanctions given the widespread belief that Tyndale changed the Bible as he attempted to translate it. Tyndale's unfinished work, cut short by his execution, was supplemented by Myles Coverdale and published under a pseudonym to create the Matthew Bible, the first complete English translation of the Bible. Attempts at an "authoritative" English Bible for the Church of England would include the Great Bible of 1538 (also relying on Coverdale's work), the Bishops' Bible of 1568, and the Authorized Version (the King James Version) of 1611, the last of which would become a standard for English speaking Christians for several centuries.

The first complete French Bible was a translation by Jacques Lefèvre d'Étaples, published in 1530 in Antwerp.[14] The Froschauer Bible of 1531 and the Luther Bible of 1534 (both appearing in portions throughout the 1520s) were an important part of the Reformation.

The first English translations of Psalms (1530), Isaiah (1531), Proverbs (1533), Ecclesiastes (1533), Jeremiah (1534) and Lamentations (1534), were executed by the Protestant Bible translator George Joye in Antwerp. In 1535 Myles Coverdale published the first complete English Bible also in Antwerp.[15]

By 1578 both Old and New Testaments were translated to Slovene by the Protestant writer and theologian Jurij Dalmatin. The work was not printed until 1583. The Slovenes thus became the 12th nation in the world with a complete Bible in their language. The translation of the New Testament was based on the work by Dalmatin's mentor, the Protestant Primož Trubar, who published the translation of the Gospel of Matthew already in 1555 and the entire testament by parts until 1577.

Samuel Bogusław Chyliński (1631–1668) translated and published the first Bible translation into Lithuanian.[16]

Modern translation efforts

The Bible is the most translated book in the world. The United Bible Societies announced that as of 31 December 2007[17] the complete Bible was available in 438 languages, 123 of which included the deuterocanonical material as well as the Tanakh and New Testament. Either the Tanakh or the New Testament was available in an additional 1,168 languages.

In 1999, Wycliffe Bible Translators announced Vision 2025—a project that intends to commence Bible translation in every remaining language community by 2025. As of 1 October 2015 they estimate that around 165 - 180 million people, speak those 1,800 languages where translation work still needs to begin. Wycliffe also stated that parts of the Bible are available in approximately 2,900 out of the 6,877 known languages, and that there are currently 554 languages with a complete Bible translation. The New Testament is available in 1,333 languages and many more have at least one book of the Bible available.[18]

Differences in Bible translations

Dynamic or formal translation policy

A variety of linguistic, philological and ideological approaches to translation have been used. Inside the Bible-translation community, these are commonly categorized as:

- Dynamic equivalence translation

- Formal equivalence translation (similar to literal translation)

- Idiomatic, or Paraphrastic translation, as used by the late Kenneth N. Taylor

though modern linguists such as Bible scholar Dr. Joel Hoffman disagrees with this classification.[19]

As Hebrew and Greek, the original languages of the Bible, like all languages, have some idioms and concepts not easily translated, there is in some cases an ongoing critical tension about whether it is better to give a word for word translation or to give a translation that gives a parallel idiom in the target language. For instance, in the New American Bible, which is the English language Catholic translation, as well as Protestant translations like the King James Version, the Darby Bible, the New Revised Standard Version, the Modern Literal Version, and the New American Standard Bible are seen as more literal translations (or "word for word"), whereas translations like the New International Version and New Living Translation sometimes attempt to give relevant parallel idioms. The Living Bible and The Message are two paraphrases of the Bible that try to convey the original meaning in contemporary language. The further away one gets from word for word translation, the easier the text becomes to read while relying more on the theological, linguistic or cultural understanding of the translator, which one would not normally expect a lay reader to require. On the other hand, as one gets closer to a word for word translation, the text becomes more literal but still relies on similar problems of meaningful translation at the word level and makes it difficult for lay readers to interpret due to their unfamiliarity with ancient idioms and other historical and cultural contexts.

Doctrinal differences and translation policy

In addition to linguistic concerns, theological issues also drive Bible translations. Some translations of the Bible, produced by single churches or groups of churches, may be seen as subject to a point of view by the translation committee.

For example, the New World Translation, produced by Jehovah's Witnesses, provides different renderings where verses in other Bible translations support the deity of Christ.[20] The NWT also translates kurios as "Jehovah" rather than "Lord" when quoting Hebrew passages that used YHWH. The authors believe that Jesus would have used God's name and not the customary kurios. On this basis, the anonymous New World Bible Translation Committee inserted Jehovah into the New World Translation of the Christian Greek Scriptures (New Testament) a total of 237 times while the New World Translation of the Hebrew Scriptures (Old Testament) uses Jehovah a total of 6,979 times to a grand total of 7,216 in the entire 2013 Revision New World Translation of the Holy Scriptures while previous revisions such as the 1984 revision were a total of 7,210 times while the 1961 revision were a total of 7,199 times. [21]

A number of Sacred Name Bibles have been published that are even more rigorous in transliterating the tetragrammaton, using Semitic forms to translate it in the Old Testament and also using the same Semitic forms to translate the Greek word Theos (God) in the New Testament, e.g. usually Yahweh and/or Elohim or some other variation, e.g. The Sacred Scriptures Bethel Edition.

Other translations are distinguished by smaller, but distinctive, doctrinal differences. For example, the Purified Translation of the Bible, by translation and explanatory footnotes, promoting the position that Christians should not drink alcohol, that New Testament references to "wine" are translated as "grape juice".

See also

- Ancient and classical translations:

- Coptic versions of the Bible

- Septuagint (Greek)

- Syriac versions of the Bible

- Targum and Peshitta (Aramaic)

- Vetus Latina and Vulgate (Latin)

- English Translations:

- Early Modern English Bible translations

- English translations of the Bible

- Jewish English Bible translations

- Old English Bible translations

- Middle English Bible translations

- Modern English Bible translations

- Other languages:

- Bible translations by language

- Bible translations into the languages of India

- Bible translations into the languages of Indonesia

- Bible translations into Ladakhi

- Difficulties:

- Gender in Bible translation

- Texas sharpshooter fallacy#Translation and interpretation

- Translation#Fidelity and transparency

- Others:

Notes

- ↑ Some scholars hypothesize that certain books (whether completely or partially) may have been written in Aramaic before being translated for widespread dissemination. One very famous example of this is the opening to the Gospel of John, which some scholars argue to be a Greek translation of an Aramaic hymn.

References

- ↑ http://www.wycliffe.net/resources/scriptureaccessstatistics/tabid/99/Default.aspx

- 1 2 Menachem Cohen, The Idea of the Sanctity of the Biblical Text and the Science of Textual Criticism in HaMikrah V'anachnu, ed. Uriel Simon, HaMachon L'Yahadut U'Machshava Bat-Z'mananu and Dvir, Tel-Aviv, 1979.

- ↑ Herbert Weir Smyth, Greek Grammar. Revised by Gordon M. Messing. ISBN 9780674362505. Harvard University Press, 1956. Introduction F, N-2, p. 4A

- ↑ http://greek-language.com/grklinguist/?p=657.

- ↑ http://www.stpaulsirvine.org/images/papyruslg.gif| shows an example of the text without punctuation

- ↑ Sundberg, Albert C., Jr. (2002). "The Septuagint: The Bible of Hellenistic Judaism". In McDonald, Lee Martin; Sanders, James A. The Canon Debate. Hendrickson Publishers. p. 72. ISBN 978-1-56563-517-3.

- ↑ Exod 24:1-8, Josephus [Antiquities 12.57, 12.86], or an elision. ...this name Septuagint appears to have been a fourth- to fifth-century development."

- ↑ Karen Jobes and Moises Silva, Invitation to the Septuagint, ISBN 1-84227-061-3 (Paternoster Press, 2001). - The as of 2001 standard introductory work on the Septuagint.

- ↑ Jennifer M. Dines, The Septuagint, Michael A. Knibb, Ed., London: T&T Clark, 2004.

- ↑ The Canon Debate, McDonald & Sanders editors, 2002, pp. 414-415, for the entire paragraph.

- ↑ Sneddon, Clive R. 1993. "A neglected mediaeval Bible translation." Romance Languages Annual 5(1): 11-16 .

- ↑ Paul Arblaster, Gergely Juhász, Guido Latré (eds) Tyndale's Testament, Brepols 2002, ISBN 2-503-51411-1, p. 120.

- ↑ Metzger, Bruce R. Manuscripts of the Greek Bible: An Introduction to Paleography (Oxford University Press, 1981) cf. Papyrus 52.

- ↑ Paul Arblaster, Gergely Juhász, Guido Latré (eds) Tyndale's Testament, Brepols 2002, ISBN 2-503-51411-1, pp. 134-135.

- ↑ Paul Arblaster, Gergely Juhász, Guido Latré (eds) Tyndale's Testament, Brepols 2002, ISBN 2-503-51411-1, pp. 143-145.

- ↑ S. L. Greenslade, The Cambridge History of the Bible: The West, from the Reformation to the Present Day. 1995, p. 134

- ↑ United Bible Society (2008). "Statistical Summary of languages with the Scriptures". Archived from the original on 8 March 2008. Retrieved 2008-03-22.

- ↑ "2015 Scripture Access Statistics" (PDF). Wycliffe Global Alliance. Retrieved 31 July 2016.

- ↑ "Formal Equivalence and Dynamic Equivalence: A False Dichotomy"

- ↑ http://www.jw.org/en/jehovahs-witnesses/faq/new-world-translation-accurate/#?insight[search_id]=ab273185-8135-4ee9-a212-210cef439f3e&insight[search_result_index]=0

- ↑ New World Translation appendix, pp. 1564-1566.

External links

- Bible Translations

- Bible translations at DMOZ

- Repackaging the Bible by Eric Marrapodi, CNN, December 24, 2008

- Bible Versions and Translations on BibleStudyTools.com

- Huge selection of Bibles in Foreign Languages - bibleinmylanguage.com

- BibleGateway.com (has many translations to select)