Transition (literary journal)

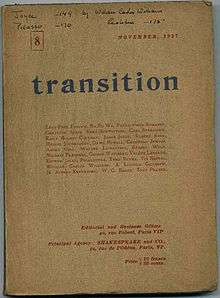

Cover of Issue 8 of literary magazine transition from November 1927 | |

| Editor | Eugene Jolas |

|---|---|

| Categories | Literary journal |

| Frequency |

Monthly (April 1927-March 1928) |

| Circulation | 1000+ |

| First issue | April 1927 |

| Final issue — Number |

Spring 1938 27 |

| Country | France |

| Based in | Paris, then Colombey-les-deux-Eglises |

| Language | English |

transition was an experimental literary journal that featured surrealist, expressionist, and Dada art and artists. It was founded in 1927 by poet Eugene Jolas and his wife Maria McDonald and published in Paris. They were later assisted by editors Elliot Paul (April 1927- March 1928), Robert Sage (October 1927-Fall 1928), and James Johnson Sweeney (June 1936-May 1938).

Origins

The literary journal was intended as an outlet for experimental writing and featured modernist, surrealist and other linguistically innovative writing and also contributions by visual artists, critics, and political activists. It ran until spring 1938. A total of 27 issues were produced. It was distributed primarily through Shakespeare and Company, the Paris bookstore run by Sylvia Beach.[1]

While it originally almost exclusively featured poetic experimentalists, it later accepted contributions from sculptors, civil rights activists, carvers, critics, and cartoonists.[1] Editors who joined the journal later on were Stuart Gilbert, Caresse Crosby and Harry Crosby.

Purpose

Published quarterly, transition also featured Surrealist, Expressionist, and Dada art. In an introduction to the first issue, Eugene Jolas wrote:

Of all the values conceived by the mind of man throughout the ages, the artistic have proven the most enduring. Primitive people and the most thoroughly civilized have always had, in common, a thirst for beauty and an appreciation of the attempts of the other to recreate the wonders suggested by nature and human experience. The tangible link between the centuries is that of art. It joins distant continents in to a mysterious unit, long before the inhabitants are aware of the universality of their impulses....

We should like to think of the readers as a homogeneous group of friends, united by a common appreciation of the beautiful, - idealists of a sort, - and to share with them what has seemed significant to us.[2]

Manifesto

The journal gained notoriety in 1929 when Jolas issued a manifesto about writing. He personally asked writers to sign "The Revolution of the Word Proclamation" which appeared in issue 16/17 of transition. It began:

Tired of the spectacle of short stories, novels, poems and plays still under the hegemony of the banal word, monotonous syntax, static psychology, descriptive naturalism, and desirous of crystallizing a viewpoint... Narrative is not mere anecdote, but the projection of a metamorphosis of reality" and that "The literary creator has the right to disintegrate the primal matter of words imposed on him by textbooks and dictionaries.[3]

The Proclamation was signed by Kay Boyle, Whit Burnett, Hart Crane, Caresse Crosby, Harry Crosby, Martha Foley, Stuart Gilbert, A. Lincoln Gillespie, Leigh Hoffman, Eugene Jolas, Elliot Paul, Douglas Rigby, Theo Rutra, Robert Sage, Harold J. Salemson, and Laurence Vail.[4]

Featured writers

Transition stories, a 1929 selection by E. Jolas and R. Sage from the first thirteen numbers featured: Gottfried Benn, Kay Boyle (Polar Bears and Others), Robert M. Coates (Conversations No. 7), Emily Holmes Coleman (The Wren's Nest), Robert Desnos, William Closson Emory (Love in the West), Léon-Paul Fargue, Konstantin Fedin, Murray Goodwin, (A Day in the Life of a Robot), Leigh Hoffman (Catastrophe), Eugene Jolas (Walk through Cosmopolis), Matthew Josephson (Lionel and Camilla), James Joyce (A Muster from Work in Progress), Franz Kafka (The Sentence), Vladimir Lidin, Ralph Manheim(Lustgarten and Christkind), Peter Negoe (Kaleidoscope), Elliot Paul (States of Sea), Georges Ribemont-Dessaignes, Robert Sage (Spectral Moorings), Kurt Schwitters (Revolution), Philippe Soupault, Gertrude Stein (As a Wife Has a Cow a Love Story)

Some other artists, authors and works published in transition included Samuel Beckett (Assumption, For Future Reference), Kay Boyle (Dedicated to Guy Urquhart), H. D. (Gift, Psyche, Dream, No, Socratic), Max Ernst (Jeune Filles en des Belles Poses, The Virgin Corrects the Child Jesus before Three Witnesses), Stuart Gilbert (The Aeolus Episode in Ulysses, Function of Words, Joyce Thesaurus Minusculus), Juan Gris (Still Life), Ernest Hemingway (Three Stories, Hills like White Elephants), Franz Kafka (The Metamorphosis), Alfred Kreymborg (from: Manhattan Anthology), Pablo Picasso (Petite Fille Lisant), Muriel Rukeyser (Lover as Fox), Gertrude Stein (An Elucidation, The Life and Death of Juan Gris, Tender Buttons, Made a Mile Away), William Carlos Williams (The Dead Baby, The Somnambulists, A Note on the Recent Work of James Joyce, Winter, Improvisations, A Voyage to Paraguay).[4]

Also Paul Bowles, Bob Brown, Kathleen Cannell, Malcolm Cowley, Hart Crane, Abraham Lincoln Gillespie Jr. (on music), Eugene Jolas (also as Theo Rutra), Marius Lyle, Robert McAlmon, Archibald McLeish Allen Tate; Bryher, Morley Callaghan, Rhys Davies, Robert Graves, Sidney Hunt, Robie Macauley, Laura Riding, Ronald Symond, Dylan Thomas.

Christian Zervos' article Picasso à Dinard was featured in the Spring 1928 issue. No. 26, 1937, with a Marcel Duchamp cover, featured Hans Arp, Man Ray, Fernand Léger, László Moholy-Nagy, Piet Mondrian, Alexander Calder and others.

A third to half the space in the early years of transition was given to translations, some of which done by Maria McDonald Jolas; French writers included: André Breton, André Gide and the Peruvian Victor Llona ; German and Austrian poets and writers included Hugo Ball, Carl Einstein, Yvan Goll, Rainer Maria Rilke, René Schickele, August Stramm, Georg Trakl; Bulgarian, Czech, Hungarian, Italian, Polish, Russian, Serbian, Swedish, Yiddish, and Native American texts were also translated.[4][5]

Perhaps the most famous work to appear in transition was Finnegans Wake, by James Joyce. Many segments of the unfinished novel were published under the name of Work in Progress.

See also

References

- 1 2 Neumann, Alice (2004). "transition Synopsis". Retrieved June 14, 2010.

- ↑ Jolas, Eugene (April 1927). "Manifesto". Retrieved June 14, 2010.

- ↑ Jolas, Eugene (1929). "Introduction". Retrieved June 14, 2010.

- 1 2 3 Neumann, Alice (2004). "transition Contributors". Retrieved June 14, 2010.

- ↑ Craig Monk: Eugene Jolas and the Translation Policies of transition. In: Mosaic, Dec. 1999.

Additional reading

- McMillan, Dougald. transition: The History of a Literary Era 1927-38. New York: George Brazillier, 1976.

- Hoffman, Frederick J. The Little Magazine: a History and a Bibliography. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1947.

- IN transition: A Paris anthology. Writing and art from transition magazine 1927-1930. With an introduction by Noel Riley Fitch. New York, London, Toronto, Sydney, Auckland: Anchor Books, Doubleday, 1990.

- Jolas, Eugene. Man from Babel. Ed. Andreas Kramer and Rainer Rumold. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1998.

- Nelson, Cary. Repression and Recovery: Modern American Poetry and the Politics of Cultural Memory, 1910-1945. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1989.

- Transition Stories, Twenty-three Stories from transition. Ed. Eugene Jolas and Robert Sage. New York: W. V. McKee, 1929.

External links

- transition Davidson College, Davidson, North Carolina. Retrieved October 5, 2005.

- transition full magazine scans at Gallica