Knee replacement

| Knee replacement | |

|---|---|

| Intervention | |

Knee replacement | |

| ICD-10-PCS | 0SRD0JZ |

| ICD-9-CM | 81.54 |

| MeSH | D019645 |

| MedlinePlus | 002974 |

| eMedicine | 1250275 |

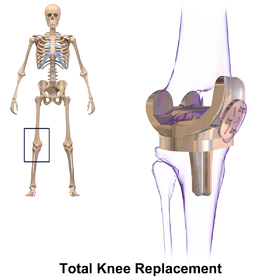

Knee replacement, also known as knee arthroplasty, is a surgical procedure to replace the weight-bearing surfaces of the knee joint to relieve pain and disability. It is most commonly performed for osteoarthritis,[1] and also for other knee diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis and psoriatic arthritis. In patients with severe deformity from advanced rheumatoid arthritis, trauma, or long-standing osteoarthritis, the surgery may be more complicated and carry higher risk. Osteoporosis does not typically cause knee pain, deformity, or inflammation and is not a reason to perform knee replacement.

Other major causes of debilitating pain include meniscus tears, cartilage defects, and ligament tears. Debilitating pain from osteoarthritis is much more common in the elderly.

Knee replacement surgery can be performed as a partial or a total knee replacement.[2] In general, the surgery consists of replacing the diseased or damaged joint surfaces of the knee with metal and plastic components shaped to allow continued motion of the knee.

The operation typically involves substantial postoperative pain, and includes vigorous physical rehabilitation. The recovery period may be 6 weeks or longer and may involve the use of mobility aids (e.g. walking frames, canes, crutches) to enable the patient's return to preoperative mobility.[3]

Medical uses

Knee replacement surgery is most commonly performed in people with advanced osteoarthritis and should be considered when conservative treatments have been exhausted.[4] Total knee replacement is also an option to correct significant knee joint or bone trauma in young patients. Similarly, total knee replacement can be performed to correct mild valgus or varus deformity. Serious valgus or varus deformity should be corrected by osteotomy. Physical therapy has been shown to improve function and may delay or prevent the need for knee replacement. Pain is often noted when performing physical activities requiring a wide range of motion in the knee joint.[5]

Risks

Risks and complications in knee replacement[6] are similar to those associated with all joint replacements. The most serious complication is infection of the joint, which occurs in <1% of patients. Risk factors for infection are related to both patient and surgical factors.[7] Deep vein thrombosis occurs in up to 15% of patients, and is symptomatic in 2–3%. Nerve injuries occur in 1–2% of patients. Persistent pain or stiffness occurs in 8–23% of patients. Prosthesis failure occurs in approximately 2% of patients at 5 years.[3]

There is increased risk in complications for obese people going through total knee replacement.[8] The morbidly obese should be advised to lose weight before surgery and, if medically eligible, would probably benefit from bariatric surgery.[9]

Fracturing or chipping of the polyethylene platform inserted onto of the tibial component may be a concern. These fragments may become lodged in the knee and create pain or may move into other parts of the body. Recent advancements in production have greatly reduced these issues but over the lifespan of the knee replacement there is such a potential.

Deep vein thrombosis

According to the American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons (AAOS), deep vein thrombosis in the leg is "the most common complication of knee replacement surgery... prevention... may include periodic elevation of patient's legs, lower leg exercises to increase circulation, support stockings and medication to thin your blood."[2]

Fractures

Periprosthetic fractures are becoming more frequent with the aging patient population and can occur intraoperatively or postoperatively.

Loss of motion

The knee at times may not recover its normal range of motion (0–135 degrees usually) after total knee replacement. Much of this is dependent on pre-operative function. Most patients can achieve 0–110 degrees, but stiffness of the joint can occur. In some situations, manipulation of the knee under anesthetic is used to reduce post operative stiffness. There are also many implants from manufacturers that are designed to be "high-flex" knees, offering a greater range of motion.

Instability

In some patients, the kneecap is unrevertable post-surgery and dislocates to the outer side of the knee. This is painful and usually needs to be treated by surgery to realign the kneecap. However this is quite rare.

In the past, there was a considerable risk of the implant components loosening over time as a result of wear. As medical technology has improved however, this risk has fallen considerably. Knee replacement implants can now last up to 20 years.

Infection

The current classification of AAOS divides prosthetic infections into four types.[10]

- Type 1 (positive intraoperative culture): Two positive intraoperative cultures

- Type 2 (early postoperative infection): Infection occurring within first month after surgery

- Type 3 (acute hematogenous infection): Hematogenous seeding of site of previously well-functioning prosthesis

- Type 4 (late chronic infection): Chronic indolent clinical course; infection present for more than a month

While it is relatively rare, periprosthetic infection remains one of the most challenging complications of joint arthroplasty. A detailed clinical history and physical remain the most reliable tool to recognize a potential periprosthetic infection. In some cases the classic signs of fever, chills, painful joint, and a draining sinus may be present, and diagnostic studies are simply done to confirm the diagnosis. In reality though, most patients do not present with those clinical signs, and in fact the clinical presentation may overlap with other complications such as aseptic loosening and pain. In those cases diagnostic tests can be useful in confirming or excluding infection.

According to a recent review the following tests can be used in the diagnosis of a periprosthetic infection.[11]

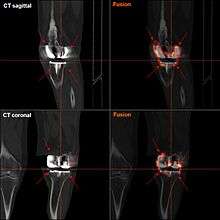

- Conventional radiograph: Rule out other conditions such as loosening and/or osteolysis.

- Radionucleotide Imaging: Technetium-99m Sulfur imaging combined with indium-111-labeled leukocytes probably offers improved specificity than either test alone. Gallium 67 scans alone have low sensitivity for infection. FDG-PET imaging has been shown to have variable specificity and sensitivity.

- Serology: Elevated serum C-reactive protein (CRP) and Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate (ESR) more than three months following arthroplasty are good screening tests.[12]

- Cultures: High sensitivity and specificity, but only if done two weeks following antibiotic discontinuation. Gram stains have low specificity and sensitivity. The predictive value of a positive culture increases if the culture is performed in patient with high clinical suspicion, rather than a screening test.

- Joint fluid leukocyte counts: A joint fluid white blood cell count of more than 500/μl is suggestive of an infection.

- Frozen sections of implant membranes: More than five white blood cells/High power field is indicative of infection.

- Newer tests: Polymerase chain reactions involving the bacterial 16S rRNA have high rates of false positives because they can detect necrotic bacterial debris even in the absence of active infection.[13]

None of the above laboratory tests has 100% sensitivity or specificity for diagnosing infection. Specificity improves when the tests are performed in patients in whom clinical suspicion exists. ESR and CRP remain good 1st line tests for screening (high sensitivity, low specificity). Aspiration of the joint remains the test with the highest specificity for confirming infection.

The choice of treatment depends on the type of prosthetic infection.[14]

- Positive intraoperative cultures: Antibiotic therapy alone

- Early post-operative infections: debridement, antibiotics, and retention of prosthesis.

- Acute hematogenous infections: debridement, antibiotic therapy, retention of prosthesis.

- Late chronic: delayed exchange arthroplasty. Surgical débridement and parenteral antibiotics alone in this group has limited success, and standard of care involves exchange arthroplasty.[15]

Appropriate antibiotic doses can be found at the following instructional course lecture by AAOS [10]

Pre-operative preparation

Knee arthroplasty is major surgery. The xray indication for a knee replacement would be weightbearing xrays of both knees- AP, Lateral, and 30 degrees of flexion. AP and lateral views may not show joint space narrowing, but the 30 degree flexion view is most sensitive for narrowing. If this view, however, does not show narrowing of the knee, then a knee replacement is not indicated. Pre-operative preparation begins immediately following surgical consultation and lasts approximately one month. The patient is to perform range of motion exercises and hip, knee and ankle strengthening as directed daily. Before the surgery is performed, pre-operative tests are done: usually a complete blood count, electrolytes, APTT and PT to measure blood clotting, chest X-rays, ECG, and blood cross-matching for possible transfusion. About a month before the surgery, the patient may be prescribed supplemental iron to boost the hemoglobin in their blood system. Accurate X-rays of the affected knee are needed to measure the size of components which will be needed. Medications such as warfarin and aspirin will be stopped some days before surgery to reduce the amount of bleeding. Patients may be admitted on the day of surgery if the pre-op work-up is done in the pre-anesthetic clinic or may come into hospital one or more days before surgery. Some hospitals offer a pre-operative seminar[16] for this surgery. Currently there is insufficient quality evidence to support the use of pre-operative physiotherapy in older adults undergoing total knee arthroplasty [17]

Preoperative education is currently an important part of patient care. There is some evidence that it may slightly reduce anxiety before knee replacement surgery, with low risk of detrimental effects. [18]

Weight loss surgery before a knee replacement does not appear to change outcomes.[19]

Technique

The surgery involves exposure of the front of the knee, with detachment of part of the quadriceps muscle (vastus medialis) from the patella. The patella is displaced to one side of the joint, allowing exposure of the distal end of the femur and the proximal end of the tibia. The ends of these bones are then accurately cut to shape using cutting guides oriented to the long axis of the bones. The cartilages and the anterior cruciate ligament are removed; the posterior cruciate ligament may also be removed[20] but the tibial and fibular collateral ligaments are preserved. Metal components are then impacted onto the bone or fixed using polymethylmethacrylate (PMMA) cement. Alternative techniques exist that affix the implant without cement. These cement-less techniques may involve osseointegration, including porous metal prostheses.

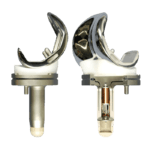

Femoral replacement

A round ended implant is used for the femur, mimicking the natural shape of the joint. On the tibia the component is flat, although it sometimes has a stem which goes down inside the bone for further stability. A flattened or slightly dished high density polyethylene surface is then inserted onto the tibial component so that the weight is transferred metal to plastic not metal to metal. During the operation any deformities must be corrected, and the ligaments balanced so that the knee has a good range of movement and is stable and aligned. In some cases the articular surface of the patella is also removed and replaced by a polyethylene button cemented to the posterior surface of the patella. In other cases, the patella is replaced unaltered.

Variations

Different implant manufacturers require slightly different instrumentation and technique. No consensus has emerged over which one is the best. Clinical studies are very difficult to perform, requiring large numbers of cases followed over many years. The most significant variations are between cemented and uncemented components and between resurfacing the patella or not. Among those who do not resurface the patella, there is also variation between denervating the patella using electrocautery or not. In theory, this technique could disrupt the superficial pain receptors near the patella in hopes of relieving anterior knee pain, a common post-operative complaint. No consensus exists, but a recent randomized controlled trial indicates that while both methods provide relief, patellar denervation results in a modest benefit compared to no denervation in the short-term. The patient satisfaction was higher with more number of patients rating the procedure as excellent in the denervation group (74.6% vs 50.8%). The benefit does not, however, persist mid- to long-term post-operatively. Anterior knee pain component within the patellar score and Visual Analogue Scale for anterior knee pain were significantly better in the denervation group at 3 months (4.5 vs 5.1) but not at 12 months (4.4 vs 4.9) and 24 months (2.1 vs. 2.2).[21]

Some also study patient satisfaction data associated with pain. Retaining the posterior cruciate ligament (PCL) has been shown to be beneficial for patients. Removal of the PCL has been shown to reduce the maximal force that the individual can place on that knee.[22] Typically individuals who have the PCL removed will lean forward while climbing in order to maximize the force of the quadriceps.

Minimally invasive procedures have been developed in total knee replacement (TKR) that do not cut the quadriceps tendon. There are different definitions of minimally invasive knee surgery, which may include a shorter incision length, retraction of the patella (kneecap) without eversion (rotating out), and specialized instruments. There are few randomized trials, but studies have found less postoperative pain, shorter hospital stays, and shorter recovery. However, no studies have shown long-term benefits.[3]

In 2015 The OGAAP team from Sydney Australia led by Dr Al Muderis presented a revolutionary technology for the first time enabling the use of knee replacement in combination with percutaneous bone anchoring device enabling amputees with short residual tibia and or knee joint arthritis to mobilise with ease. This technology provided a solution for individuals with amputation who are unable to wear a traditional socket prosthesis.[23]

Total knee replacement with the minimum of every invasive step is called “Zero Technique”. This technique comes with many advantages. Dr. Vikram I. Shah’s ‘Zero Technique' has revolutionized Total Knee Replacement Surgery, worldwide.[24]

Partial knee replacement

Unicompartmental arthroplasty (UKA), also called partial knee replacement, is an option for some patients. The knee is generally divided into three "compartments": medial (the inside part of the knee), lateral (the outside), and patellofemoral (the joint between the kneecap and the thighbone). Most patients with arthritis severe enough to consider knee replacement have significant wear in two or more of the above compartments and are best treated with total knee replacement.[25] A minority of patients (the exact percentage is hotly debated but is probably between 10 and 30 percent) have wear confined primarily to one compartment, usually the medial, and may be candidates for unicompartmental knee replacement. Advantages of UKA compared to TKA include smaller incision, easier post-op rehabilitation, better post-operative range of motion, shorter hospital stay, less blood loss, lower risk of infection, stiffness, and blood clots, but a harder revision if necessary. While most recent data suggests that UKA in properly selected patients has survival rates comparable to TKA, most surgeons believe that TKA is the more reliable long term procedure. Persons with infectious or inflammatory arthritis (Rheumatoid, Lupus, Psoriatic ), or marked deformity are not candidates for this procedure.

Post-operative rehabilitation

The length of post-operative hospitalization is 5 days on average depending on the health status of the patient and the amount of support available outside the hospital setting.[26] Protected weight bearing on crutches or a walker is required until specified by the surgeon [27] because of weakness in the quadriceps muscle[28]

To increase the likelihood of a good outcome after surgery, multiple weeks of physical therapy is necessary. In these weeks, the therapist will help the patient return to normal activities, as well as prevent blood clots, improve circulation, increase range of motion, and eventually strengthen the surrounding muscles through specific exercises.[27] Treatment includes encouraging patients to move early after the surgery. [29] Often range of motion (to the limits of the prosthesis) is recovered over the first two weeks (the earlier the better). Over time, patients are able to increase the amount of weight bearing on the operated leg, and eventually are able to tolerate full weight bearing with the guidance of the physical therapist.[27] After about ten months, the patient should be able to return to normal daily activities, although the operated leg may be significantly weaker than the non-operated leg.[28]

For knee replacement without complications, continuous passive motion (CPM) can improve recovery.[29] Additionally, CPM is inexpensive, convenient, and assists patients in therapeutic compliance. However, CPM should be used in conjunction with traditional physical therapy.[29] In unusual cases where the person has a problem which prevents standard mobilization treatment, then CPM may be useful.[29]

Some physicians and patients may consider having lower limbs venous ultrasonography to screen for deep vein thrombosis after knee replacement.[30] However, this kind of screening should be done only when indicated because to perform it routinely would be unnecessary health care.[30] If a medical condition exists that could cause deep vein thrombosis, a physician can choose to treat patients with cryotherapy and intermittent pneumatic compression as a preventive measure.[31]

Neither gabapentin nor pregabalin have been found to be useful for pain following a knee replacement.[32]

Epidemiology

With 718,000 hospitalizations, knee arthroplasty accounted for 4.6% of all United States operating room procedures in 2011—making it one of the most common procedures performed during hospital stays.[33][34] The number of knee arthroplasty procedures performed in U.S. hospitals increased 93% between 2001 and 2011.[35] A study of United States community hospitals showed that in 2012, among hospitalizations that involved an OR procedure, knee arthroplasty was the OR procedure performed most frequently during hospital stays paid by Medicare (10.8 percent of stays) and by private insurance (9.1 percent). Knee arthroplasty was not among the top five most frequently performed OR procedures for stays paid by Medicaid or for uninsured stays.[36]

By 2030, the demand for primary total knee arthroplasty is projected to increase to 3.48 million surgeries performed annually in the U.S.[37]

See also

- Autologous chondrocyte implantation

- Microfracture surgery

- Knee osteoarthritis

- Osseointegration

- Meniscus transplant

References

- ↑ Simon H Palmer (Jun 27, 2012). "Total Knee Arthroplasty". Medscape Reference.

- 1 2 "Total Knee Replacement". American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons. December 2011.

- 1 2 3 Leopold SS (April 2009). "Minimally invasive total knee arthroplasty for osteoarthritis". N. Engl. J. Med. 360 (17): 1749–58. doi:10.1056/NEJMct0806027. PMID 19387017.

- ↑ Van Manen, MD; Nace, J; Mont, MA (November 2012). "Management of primary knee osteoarthritis and indications for total knee arthroplasty for general practitioners.". The Journal of the American Osteopathic Association. 112 (11): 709–715. PMID 23139341.

- ↑ Deyle GD, Henderson NE, Matekel RL, Ryder MG, Garber MB, Allison SC (February 2000). "Effectiveness of manual physical therapy and exercise in osteoarthritis of the knee. A randomized, controlled trial". Ann. Intern. Med. 132 (3): 173–81. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-132-3-200002010-00002. PMID 10651597.

- ↑ http://www.vims.ac.in/healthcare/joint-replace-recovery-process.html

- ↑ Tayton, E. R.; Frampton, C.; Hooper, G. J.; Young, S. W. (2016-03-01). "The impact of patient and surgical factors on the rate of infection after primary total knee arthroplasty". Bone Joint J. 98–B (3): 334–340. doi:10.1302/0301-620X.98B3.36775. ISSN 2049-4394. PMID 26920958.

- ↑ Kerkhoffs, GM; Servien, E; Dunn, W; Dahm, D; Bramer, JA; Haverkamp, D (Oct 17, 2012). "The influence of obesity on the complication rate and outcome of total knee arthroplasty: a meta-analysis and systematic literature review.". The Journal of bone and joint surgery. American volume. 94 (20): 1839–44. doi:10.2106/JBJS.K.00820. PMID 23079875.

- ↑ Samson AJ, Mercer GE, Campbell DG (September 2010). "Total knee replacement in the morbidly obese: a literature review". ANZ J Surg. 80 (9): 595–9. doi:10.1111/j.1445-2197.2010.05396.x. PMID 20840400.

- 1 2 Leone JM, Hanssen AD (2006). "Management of infection at the site of a total knee arthroplasty". Instr Course Lect. 55: 449–61. PMID 16958480.

- ↑ Bauer TW, Parvizi J, Kobayashi N, Krebs V (2006). "Diagnosis of periprosthetic infection". J Bone Joint Surg Am. 88 (4): 869–82. doi:10.2106/JBJS.E.01149. PMID 16595481.

- ↑ Spangehl MJ, Masri BA, O'Connell JX, Duncan CP (1999). "Prospective analysis of preoperative and intraoperative investigations for the diagnosis of infection at the sites of two hundred and two revision total hip arthroplasties". J Bone Joint Surg Am. 81 (5): 672–83. PMID 10360695.

- ↑ Corless CE, Guiver M, Borrow R, Edwards-Jones V, Kaczmarski EB, Fox AJ (2000). "Contamination and sensitivity issues with a real-time universal 16S rRNA PCR". J. Clin. Microbiol. 38 (5): 1747–52. PMC 86577

. PMID 10790092.

. PMID 10790092. - ↑ Segawa H, Tsukayama DT, Kyle RF, Becker DA, Gustilo RB (1999). "Infection after total knee arthroplasty. A retrospective study of the treatment of eighty-one infections". J Bone Joint Surg Am. 81 (10): 1434–45. PMID 10535593.

- ↑ Chiu FY, Chen CM (2007). "Surgical débridement and parenteral antibiotics in infected revision total knee arthroplasty". Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 461: 130–5. doi:10.1097/BLO.0b013e318063e7f3. PMID 17438469.

- ↑ Before surgery, your orthopaedic surgeon will make some recommendations, such as suggesting that you: Donate some of your own blood so that, if needed, you may receive it during or after surgery Stop taking some drugs before surgery. http://www.vims.ac.in/healthcare/joint-replace-recovery-process.html

- ↑ Chesham, Ross Alexander; Shanmugam, Sivaramkumar (13 October 2016). "Does preoperative physiotherapy improve postoperative, patient-based outcomes in older adults who have undergone total knee arthroplasty? A systematic review". Physiotherapy Theory and Practice: 1–22. doi:10.1080/09593985.2016.1230660. PMID 27736286.

- ↑ McDonald, S; Page, MJ; Beringer, K; Wasiak, J; Sprowson, A (13 May 2014). "Preoperative education for hip or knee replacement". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (5): CD003526. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003526.pub3. PMID 24820247.

- ↑ Smith, TO; Aboelmagd, T; Hing, CB; MacGregor, A (September 2016). "Does bariatric surgery prior to total hip or knee arthroplasty reduce post-operative complications and improve clinical outcomes for obese patients? Systematic review and meta-analysis.". The bone & joint journal. 98–B (9): 1160–6. PMID 27587514.

- ↑ Jacobs, WC; Clement, DJ; Wymenga, AB (Oct 19, 2005). "Retention versus sacrifice of the posterior cruciate ligament in total knee replacement for treatment of osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis.". The Cochrane database of systematic reviews (4): CD004803. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004803.pub2. PMID 16235383.

- ↑ Pulavarti RS1, Raut VV, McLauchlan GJ. (May 2014). "Patella Denervation in Primary Total Knee Arthroplasty - A Randomized Controlled Trial with 2Years of Follow-Up.". J Arthroplasty. 29 (5): 977–81. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2013.10.017. PMID 24291230.

- ↑ Mahoney OM, Noble PC, Rhoads DD, Alexander JW, Tullos HS (December 1994). "Posterior cruciate function following total knee arthroplasty. A biomechanical study". J Arthroplasty. 9 (6): 569–78. doi:10.1016/0883-5403(94)90110-4. PMID 7699369.

- ↑ Khemka A, Frossard L, Lord SJ, Bosley B, Al Muderis M (2015). "Osseointegrated total knee replacement connected to a lower limb prosthesis: 4 cases". Acta Orthop. 86: 740–4. doi:10.3109/17453674.2015.1068635. PMC 4750776

. PMID 26145721.

. PMID 26145721. - ↑ ""Zero Technique" – Revolutionizing Total Knee Replacement (TKR)". Briefing Wire.

- ↑ Unicompartmental vs. Total Knee Replacement By Dr. Gregory Markarian. Retrieved January 29, 2015.

- ↑ Carter, Evelene M; Potts, Henry WW (2014). "Predicting length of stay from an electronic patient record system: a primary total knee replacement example". BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making. 14 (1): 26. doi:10.1186/1472-6947-14-26. ISSN 1472-6947.

- 1 2 3 "Rehabilitation" (PDF). massgeneral.org.

- 1 2 Valtonen, Anu; Pöyhönen, Tapani; Heinonen, Ari; Sipilä, Sarianna (2009-10-01). "Muscle Deficits Persist After Unilateral Knee Replacement and Have Implications for Rehabilitation". Physical Therapy. 89 (10): 1072–1079. doi:10.2522/ptj.20070295. ISSN 0031-9023. PMID 19713269.

- 1 2 3 4 American Physical Therapy Association (15 September 2014), "Five Things Physicians and Patients Should Question", Choosing Wisely: an initiative of the ABIM Foundation, American Physical Therapy Association, retrieved 15 September 2014, which cites

- Harvey, LA; Brosseau, L; Herbert, RD (Mar 17, 2010). "Continuous passive motion following total knee arthroplasty in people with arthritis.". Cochrane database of systematic reviews (Online) (3): CD004260. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004260.pub2. PMID 20238330.

- 1 2 American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (February 2013), "Five Things Physicians and Patients Should Question", Choosing Wisely: an initiative of the ABIM Foundation, American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons, retrieved 19 May 2013, which cites

- Members of 2007 and 2011 AAOS Guideline Development Work Groups on PE/VTED Prophylaxis; Mont, M; Jacobs, J; Lieberman, J; Parvizi, J; Lachiewicz, P; Johanson, N; Watters, W (Apr 18, 2012). "Preventing venous thromboembolic disease in patients undergoing elective total hip and knee arthroplasty.". The Journal of bone and joint surgery. American volume. 94 (8): 673–4. doi:10.2106/JBJS.9408edit. PMC 3326687

. PMID 22517384.

. PMID 22517384.

- Members of 2007 and 2011 AAOS Guideline Development Work Groups on PE/VTED Prophylaxis; Mont, M; Jacobs, J; Lieberman, J; Parvizi, J; Lachiewicz, P; Johanson, N; Watters, W (Apr 18, 2012). "Preventing venous thromboembolic disease in patients undergoing elective total hip and knee arthroplasty.". The Journal of bone and joint surgery. American volume. 94 (8): 673–4. doi:10.2106/JBJS.9408edit. PMC 3326687

- ↑ Dallan C. Manscill (June 16, 2015). "Intermittent Pneumatic Compression and Treating Deep Vein Thrombosis & Pulmonary Embolism". Healthcare Fitness.

- ↑ Hamilton, TW; Strickland, LH; Pandit, HG (17 August 2016). "A Meta-Analysis on the Use of Gabapentinoids for the Treatment of Acute Postoperative Pain Following Total Knee Arthroplasty.". The Journal of bone and joint surgery. American volume. 98 (16): 1340–50. PMID 27535436.

- ↑ Pfuntner A., Wier L.M., Stocks C. Most Frequent Procedures Performed in U.S. Hospitals, 2011. HCUP Statistical Brief #165. October 2013. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, MD. .

- ↑ Weiss AJ, Elixhauser A, Andrews RM (February 2014). "Characteristics of Operating Room Procedures in U.S. Hospitals, 2011.". HCUP Statistical Brief #170. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

- ↑ Weiss AJ, Elixhauser A (March 2014). "Trends in Operating Room Procedures in U.S. Hospitals, 2001—2011.". HCUP Statistical Brief #171. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

- ↑ Fingar KR, Stocks C, Weiss AJ, Steiner CA (December 2014). "Most Frequent Operating Room Procedures Performed in U.S. Hospitals, 2003-2012". HCUP Statistical Brief #186. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

- ↑ "Essential amino acid supplementation in patients following total knee arthroplasty". J Clin Invest. 123 (11): 4654–4666. 2013. doi:10.1172/JCI70160.

External links

- A New Set of Knees Comes at a Price: A Whole Lot of Pain By Jane E. Brody, The New York Times, February 8, 2005

- When It Comes to Severe Pain, Doctors Still Have Much to Learn By Jane E. Brody, The New York Times, February 15, 2005

- A Year With My New Knees: Much Pain but Much Gain By Jane E. Brody, The New York Times, December 20, 2005

- 3 Years Later, Knees Made for Dancing, By Jane E. Brody, The New York Times, June 3, 2008

- Relief for Joints Besieged by Arthritis, By Jane E. Brody, The New York Times, July 9, 2012