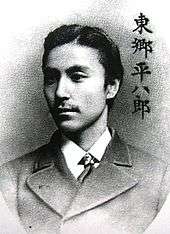

Tōgō Heihachirō

| Marshal-Admiral The Marquis Tōgō Heihachirō Saneyoshi | |

|---|---|

| |

| Nickname(s) | "The Nelson of the East" |

| Born |

27 January 1848 Kajiya-Chō, Kagoshima-Jōka, Satsuma, Japan |

| Died |

30 May 1934 (aged 86) Tokyo, Japan |

| Allegiance |

|

| Service/branch |

|

| Years of service | 1863–1913 |

| Rank | Marshal-Admiral |

| Battles/wars |

Anglo-Satsuma War Boshin War First Sino-Japanese War Russo-Japanese War |

| Awards |

Collar of the Supreme Order of the Chrysanthemum Order of the Golden Kite (First Class) Grand Cordon of the Order of the Rising Sun Grand Cordon of the Order of the Sacred Treasure Order of Merit Honorary Knight Grand Cross of the Royal Victorian Order |

| Other work | tutor to Crown Prince Hirohito |

Marshal-Admiral Marquis Tōgō Heihachirō, OM, GCVO (東郷 平八郎; 27 January 1848 – 30 May 1934), was a gensui or admiral of the fleet in the Imperial Japanese Navy and one of Japan's greatest naval heroes. He was termed by Western journalists as "the Nelson of the East".

Early life

Tōgō was born on 27 January 1848 in the Kajiya-chō (加治屋町) district of the city of Kagoshima in Satsuma domain (modern-day Kagoshima Prefecture), in feudal Japan, the third of four sons of Togo Kichizaemon,[1] a samurai serving the Shimazu daimyō, and Hori Masuko (1812–1901).

Kajiya-chō was one of Kagoshima's samurai housing-districts, in which many other influential figures of the Meiji period were born, such as Saigō Takamori and Ōkubo Toshimichi. They rose to prominent positions under the Meiji Emperor partly because the Shimazu clan had been a decisive military and political factor in the Boshin War against the Tokugawa shogunate during the Meiji Restoration.

Tokugawa conflicts (1863–1869)

Tōgō's first experience at war was at the age of 15 during the Bombardment of Kagoshima (August 1863), in which Kagoshima was shelled by the Royal Navy to punish the Satsuma daimyō for the death of Charles Lennox Richardson on the Tōkaidō highway the previous year (the Namamugi Incident), and the Japanese refusal to pay an indemnity in compensation.

The following year, Satsuma established a navy, in which Tōgō and two of his brothers enrolled. In January 1868, during the Boshin War, Tōgō was assigned to the paddle-wheel steam warship Kasuga, which participated in the Battle of Awa, near Osaka, against the navy of the Tokugawa Bakufu, the first Japanese naval battle between two modern fleets.

As the conflict spread to northern Japan, Tōgō participated as a third-class officer aboard the Kasuga in the last battles against the remnants of the Bakufu forces, the Battle of Miyako Bay and the Battle of Hakodate (1869).

After the civil war was over in the Autumn of 1869, Tōgō, on the instructions of the Satsuma clan, first travelled to the treaty port of Yokohama to study English. He resided in Yokohama with Daisuke Shibata, a government official reputedly proficient in English and received additional pronunciation coaching from Charles Wagman, Japan correspondent of the The Illustrated London News. Tōgō made rapid progress in his studies and in 1870 secured a place at the newly established Imperial Japanese Navy Training School at Tsukiji, Tokyo. On 11 December 1870 he was formally appointed a cadet on the Japanese ironclad flagship Ryūjō, then at anchor in Yokohama harbour.[2]

Studies in Britain (1871–1878)

In February 1871, Tōgō and eleven other Japanese officer cadets were selected to travel to England to further their naval studies. Between extensive practical sea training and an extended voyage to Australia, Tōgō lived and studied in England for a period of seven years. Arriving in April 1871 after a journey of 80 days at the port of Southampton, Tōgō first travelled to London, at that time the largest and most populous city in the world. According to contemporary accounts of the cadet's first days in England, many things were strange to Japanese eyes at that time; the domed buildings made out of stone, the "number and massiveness of the buildings", "the furnishings of a commonplace European room", and "the displays in the butchers' shop windows: it took them several days to become accustomed to such an abundance of meat."[3]

The Japanese group was separated and sent to English boardinghouses for individual instruction in English language, customs and manners. Tōgō was initially sent for some weeks to a boarding house in the major naval port of Plymouth, to gain some understanding of the British Royal Navy. Subsequently, he studied history, mathematics and engineering at a naval preparatory school in Portsmouth under the direction of a tutor and local clergyman in order to prepare for admission to Royal Naval College at Dartmouth.

After the British Admiralty decided in 1872 that no places were to be made available at Dartmouth for the Japanese cadets, Tōgō was able gain admission as a cadet on HMS Worcester, the training ship of the Thames Nautical Training College moored at Greenhithe.[4] Tōgō found his cadet rations "inadequate": "I swallowed my small rations in a moment. I formed the habit of dipping my bread in my tea and eating a great deal of it, to the surprise of my English comrades." Tōgō's comrades called him "Johnny Chinaman", being unfamiliar with the "Orient", and not knowing the difference between Asiatic peoples. "The young samurai did not like that, and on more than one occasion he would threaten to put an end to it by blows." Gunnery training for the college was held aboard Nelson's flagship HMS Victory, at the time moored in Portsmouth harbour. Tōgō is recorded to have attended Trafalgar Day observances on the deck of the ship in 1873. After two years of training, Tōgō was to graduate second in his class.

During 1875, Tōgō circumnavigated the world as an ordinary seaman on the British training-ship Hampshire, leaving in February and staying seventy days at sea without a port call until reaching Melbourne. Tōgō 'observed the strange animals on the Southern continent.' Rounding Cape Horn on his return voyage, Tōgō had sailed thirty thousand miles before returning to England in September 1875. During the autumn and winter of 1875-1876, Tōgō spent five months in Cambridge studying mathematics and English under the direction of the Rev. Arthur Douglas Capel.[5] The Rev. Capel was at the time of Tōgō's visit, both a mathematics tutor and curate at the Anglican church of St. Mary the Less in Cambridge. Tōgō is recorded to have attended services at the same church during his stay.

In 1875 Tōgō suffered a bout of illness which severely threatened his eyesight: "the patient asked his medical advisers to 'try everything', and some of their experiments were extremely painful." Rev. Capel commented later, "If I had not seen with my own eyes what a Japanese can suffer without complaint, I should often have been disinclined to believe ... But, having observed Tōgō, I believe all of them." Harley Street ophthalmologists were able to save his eyesight. Upon recovery Tōgō travelled to Portsmouth to continue his training before being assigned the role of inspector for the construction of the Fusō, one of three new warships ordered by the Imperial Japanese Navy. Residing in proximity to the Royal Naval College, Greenwich, Tōgō made use of the opportunity to apply his training, observing the construction of the ship at the Samuda Brothers shipyard on the Isle of Dogs.

Tōgō, newly promoted to lieutenant finally returned to Japan on 22 May 1878 aboard one of the newly purchased British-built ships, the Hiei. Tōgō was absent from Japan during the Satsuma Rebellion, and often expressed regret for the fate of his benefactor Saigō Takamori.

In 1878 Tōgō was promoted to the rank of first lieutenant of the Japanese built paddle-steamer warship Jiingei, later to be transferred to the corvette Amagi. In 1882, Tōgō led his ship's company in landing troops at Seoul in the wake of the Imo Incident.

Sino-French War (1884–1885)

On his return to Japan Tōgō received several commands, first as captain of Daini Teibō, and then Amagi. During the Franco-Chinese War (1884–1885), Tōgō, onboard Amagi, closely followed the actions of the French fleet under Admiral Courbet.

Tōgō also observed the ground combat of the French forces against the Chinese in Formosa (Taiwan), under the guidance of Joseph Joffre, future Commander-in-Chief of French forces during World War I.

Although first promoted to the rank of Captain in 1886, Tōgō suffered from a bout of acute rheumatism during the late 1880s that confined him to bed rest for nearly three years. He used this period of enforced absence from front line naval duties to study aspects of international and maritime law.[6]

Sino-Japanese War (1894–1895)

In 1891 Tōgō's health had sufficiently recovered that he was appointed to the command of the cruiser Naniwa. 1894, at the beginning of the First Sino-Japanese War, Tōgō, as a captain of the Naniwa, sank the British transport ship, Kowshing, which was chartered by the Chinese Beiyang Fleet to convey troops. A report of the incident was sent by Suematsu Kenchō to Mutsu Munemitsu.

The sinking almost caused a diplomatic conflict between Japan and Great Britain, but it was finally recognised by British jurists as in total conformity with International Law, making Tōgō famous overnight for his mastery of contentious issues involving foreign countries and regulations. The British merchant ship had under command of an English captain, T.R. Galsworthy, been ferrying more than a thousand Chinese soldiers towards Korea, and these soldiers had mutinied and taken over the ship upon the appearance and threats from the Japanese warships. Captain Galsworthy, a key figure in the dispute, had incidentally been one of Tōgō's instructors as a young cadet on HMS Worcester.

A contemporary account from a German survivor, Major von Hannecken stated that the Chinese survivors had been fired upon, sinking two lifeboats. "...By this time only the Kowshing's masts were visible.The water was however covered with Chinese, and there were two lifeboats from the Kowshing crowded with soldiers. The Japanese officer informed me that he had been ordered by signal from the Naniwa to sink these boats. I remonstrated, but he fired two volleys from the cutter, turned back, and steamed for the Naniwa. No attempt was made to rescue the Chinese. The Naniwa steamed about until eight o'clock in the evening, but did not pick up any other Europeans ..."[7]

He later took part in the Battle of the Yalu, with the Naniwa as the last ship in the line of battle under the overall command of Admiral Tsuboi Kōzō. Togo was promoted to rear admiral at the end of the war, in 1895.

After the end of the Sino-Japanese War, Tōgō was successively commandant of the Naval War College, commander of the Sasebo Naval College, and Commander of the Standing Fleet.

Russo-Japanese War (1904–1905)

In 1903, the Navy Minister Yamamoto Gonnohyōe appointed Tōgō Commander-in-Chief of the Combined Fleet of the Imperial Japanese Navy. This astonished many people, including Emperor Meiji, who asked Yamamoto why Tōgō was appointed. Yamamoto replied to the emperor, "Because Tōgō is a man of good fortune".

During the Russo-Japanese War, Tōgō engaged the Russian navy at Port Arthur and the Yellow Sea in 1904, and to widespread international acclaim commanded the Japanese naval forces at the destruction of the Imperial Russian Navy's Baltic Fleet at the Battle of Tsushima in May 1905.

The Battle of Tsushima was considered a daring naval victory pitting a small, but rapidly militarising emerging Asian nation against a major European adversary. Russia was at the time the world's third largest naval power. While the Japanese fleet at Tsushima lost only three torpedo boats under Tōgō's command, of the 36 Russian warships that went into action, 22 were sunk, six were captured, six were interned in neutral ports and only three escaped to the safety of Vladivostok.

Tsushima broke Russian naval dominance in East Asia, and is said to have been a contributing factor in subsequent uprisings in the Russian Navy (1905 uprisings in Vladivostok and the Battleship Potemkin uprising), contributing to the Russian Revolution of 1905.

Post war investigations were held of Russian naval leaders during those battles in which Tōgō had prevailed, seeking the reasons behind their utter defeat. The Russian commander of the destroyed Baltic fleet, Admiral Zinovy Rozhdestvenski (who was badly wounded in the battle) attempted to take full responsibility for the disaster, and the authorities (and rulers of Russia) acquitted him at his trial. However, they made Admiral Nikolai Nebogatov, who had tried to blame the Russian Government, a scapegoat. Nebogatov was found guilty and sentenced to ten years imprisonment in a fortress, but was released by the Tsar after serving only two years.

Later life

Tōgō kept his journals in English, and wrote, "I am firmly convinced that I am the re-incarnation of Horatio Nelson."[8] In 1906, he was made a Member of the British Order of Merit by King Edward VII.[9]

Tōgō was Chief of the Naval General Staff and was given the title of hakushaku (Count) under the kazoku peerage system. He also served as a member of the Supreme War Council. In 1911, Tōgō returned to England for the first time in over 30 years to attend the coronation of King George V, the Coronation Fleet Review at Portsmouth, to attend naval alumni dinners and visit dockyards on the Clyde and in Newcastle.

In 1913, Admiral Tōgō received the honorific title of Marshal-Admiral, which is roughly equivalent to the rank of Grand Admiral or Admiral of the Fleet in other navies. From 1914 to 1924, Gensui Tōgō was put in charge of the education of Crown Prince Hirohito, the future Shōwa Emperor.

Tōgō publicly expressed a dislike and lack of interest for involvement in politics; however, he did make strong statements against the London Naval Treaty.

Tōgō was awarded the Collar of the Supreme Order of the Chrysanthemum in 1926, an honour that was held only by Emperor Hirohito and Prince Kan'in Kotohito at the time; the award made him Japan's most decorated naval officer ever. He added the award to his existing Order of the Golden Kite (1st class) and already existing Order of the Chrysanthemum. His peerage was raised to that of koshaku (marquis) in 1934, a day before his death.

On his death in 1934, at the age of 86, he was accorded a state funeral. The navies of Great Britain, United States, Netherlands, France, Italy and China all sent ships to a naval parade in his honour in Tokyo Bay.

In 1940, Tōgō Jinja was built in Harajuku, Tokyo, as the naval rival to the Nogi Shrine erected in the honour of Imperial Japanese Army General Nogi Maresuke. The idea of elevating him to a Shinto kami had been discussed before his death, and he had been vehemently opposed to the idea. There is another Tōgō shrine at Tsuyazaki, Fukuoka. The statues to him in Japan include one at Ontaku Shrine, in Agano, Saitama and one in front of the memorial battleship Mikasa in Yokosuka.

Tōgō's son and grandson also served in the Imperial Japanese Navy. His grandson died in combat during the Pacific War on the heavy cruiser Maya at the Battle of Leyte.

In 1958, Fleet Admiral Chester Nimitz, an admirer of Gensui The Marquis Tōgō, helped to finance the restoration of the Mikasa, Admiral Tōgō's flagship during the Russo-Japanese war. In exchange, Japanese craftsmen assembled a Japanese "Garden of Peace," a replica of Marshal-Admiral Tōgō's garden, at the National Museum of the Pacific War (formerly known as The Nimitz Museum) in Fredericksburg, Texas.[10]

Honours

Incorporates information from the corresponding Japanese Wikipedia article [11]

Tōgō's career promotionsRanks

Titles

|

Japanese

Fourth Class of the Order of the Rising Sun (20 August 1895)

Fourth Class of the Order of the Rising Sun (20 August 1895) Fourth Class of the Order of the Golden Kite (20 August 1895)

Fourth Class of the Order of the Golden Kite (20 August 1895) Grand Cordon of the Order of the Rising Sun (19 July 1901)

Grand Cordon of the Order of the Rising Sun (19 July 1901) Grand Cordon of the Order of the Golden Kite (1 April 1906)

Grand Cordon of the Order of the Golden Kite (1 April 1906) Grand Cordon of the Order of the Chrysanthemum (1 April 1906)

Grand Cordon of the Order of the Chrysanthemum (1 April 1906)- Count (September 1907)

Collar of the Order of the Chrysanthemum (11 November 1926)

Collar of the Order of the Chrysanthemum (11 November 1926)- Marquess (29 May 1934)

- Junior First Rank (30 May 1934; posthumously) (Senior second rank: 1918; Second rank: 1911; Senior third rank: 1906)

Foreign

- Belgium: Grand Cordon in the Order of Leopold.1907 [12]

- Empire of Korea: Grand Collar of the Order of the Golden Ruler (the then highest decoration) (1906)

- United Kingdom: Member of the Order of Merit (OM) (21 February 1906)[13]

- United Kingdom: Honorary Knight Grand Cross of the Royal Victorian Order (GCVO)

- Kingdom of Italy: Knight Grand Cross of the Order of Saints Maurice and Lazarus

- France: Grand Officer of the Legion of Honour

- Poland: Grand Cross of the Order of Polonia Restituta

- Russian Empire: Order of St. Anna, 1st Class

- Spain: Order of Naval Merit, 4th Class

Family

Tōgō's wife was Kaeda Tetsu (1861–1934). The couple had two sons; the elder son, Takeshi (1885–1969), succeeded his father as the second Marquess Togo in 1934 and held the title until the kazoku was abolished in 1947. The younger, Rear-Admiral Tōgō Minoru (1890–1962) followed his father into the navy, rising to the rank of rear-admiral and ending his career in 1943 as commander of the naval district in Fukuoka. His elder son Ryoichi, who became a naval lieutenant, was killed in action during the Second World War.

Takeshi married Ohara Haruko (1899–1985); the couple had one son, Kazuo (1919–1991) and two daughters, Ryoko (1917–1972) and Momoko (1925–). Kazuo married Amano Tamiko and had three daughters, Kikuko (1948–), Shoko (1952–) and Muneko (1956–). As Kazuo and his wife never had sons, to perpetuate the Tōgō name they adopted their son-in-law, Maruyama Yoshio (1942–), the husband of Kikuko. Kikuko and Yoshio have two sons; the elder, Yoshihisa (1971–), married Niimi Miyuki and has two sons, Ryuuta (1991–) and Masahei (1993–). [11]

On film

Tōgō was portrayed by Toshiro Mifune in the 1969 Japanese film The Battle of the Japan Sea (『日本海大海戦』):

- Title: The Battle of the Japan Sea

- Release date: 1969

- Directed by Seiji Maruyama

- Starring: Toshiro Mifune as Admiral Tōgō

- Music by Masaru Sato

- Special effects by Eiji Tsuburaya

See also

- Anglo-Japanese relations

- Japanese battleship Mikasa – Tōgō's flagship at the Battle of Tsushima

- List of people on the cover of Time magazine (1920s) – 8 November 1926

- Togo – Siberian Husky sled dog named after Japanese admiral Tōgō

- Togo, Saskatchewan

References

- ↑ http://www.allworldwars.com/The-Life-of-Admiral-Togo-by-Arthur-Lloyd.html#III

- ↑ Ikeda, Kiyoshi (1994). Nish, Ian, ed. Britain & Japan: Biographical Portraits. Folkstone: Japan Library. p. 108. ISBN 1-873410-27-1.

- ↑ Blonde, Georges (1961). Admiral Togo. London: Jarrolds Publishers. p. 55.

- ↑ Blond, pp.56–7

- ↑ Cobbing, Andrew (1998). The Japanese Discovery of Victorian Britain. Abingdon, Oxford: Routledge. p. 122. ISBN 1-873410-81-6.

- ↑ Ikeda, Kiyoshi (1994). Nish, Ian, ed. Britain & Japan: Biographical Portraits. Folkstone: Japan Library. p. 110. ISBN 1-873410-27-1.

- ↑ http://sinojapanesewar.com/pungdo.htm

- ↑ Garson, R. W. (January 1999). "Three Great Admirals – One Common Spirit?" (PDF). The Naval Review. 87 (1): 63–64.

- ↑

"Togo, Heihachiro". Encyclopædia Britannica. 26 (11th ed.). 1911. p. 1046.

"Togo, Heihachiro". Encyclopædia Britannica. 26 (11th ed.). 1911. p. 1046. - ↑ Japanese Garden of Peace

- 1 2 Togo genealogy

- ↑ Nieuws Van Den Dag (Het) 07-07-1907

- ↑ The London Gazette, 15 May 1906

Further reading

- Andidora, Ronald. Iron Admirals: Naval Leadership in the Twentieth Century. Greenwood Press (2000). ISBN 0-313-31266-4

- Blond, Georges. Admiral Togo. Jarrolds (1961). ASIN: B0006D6WIK

- Clements, Jonathan. Admiral Togo: Nelson of the East. Haus (2010) ISBN 978-1-906598-62-4

- Bodley, R. V. C., Admiral Togo: The authorised life of Admiral of the Fleet, Marquis Heihachiro Togo. Jarrolds (1935). ASIN: B00085WDKM

- Dupuy, Trevor N. Encyclopedia of Military Biography. I B Tauris & Co Ltd (1992). ISBN 1-85043-569-3

- Ikeda, Kiyoshi. The Silent Admiral: Togo Heihachiro (1848–1934) and Britain, from Britain & Japan: Biographical Portraits Volume One, Chapter 9. Japan Library (1994) ISBN 1-873410-27-1

- Jukes, Jeffery. The Russo-Japanese War 1904–1905. Osprey Publishing (2002).ISBN 1841764469

- Schencking, J. Charles. Making Waves: Politics, Propaganda, and the Emergence of the Imperial Japanese Navy, 1868–1922. Stanford University Press (2005). ISBN 0-8047-4977-9

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Tōgō Heihachirō. |

- Togo, Heihachiro | Portraits of Modern Japanese Historical Figures of National Diet Library

- Heihachirō Tōgō at Flickr Commons

- Togo Jinja (Shrine) at Find a Grave

- Heihachiro Togo at Find a Grave