Through the Looking-Glass

First edition cover of Through the Looking-Glass | |

| Author | Lewis Carroll |

|---|---|

| Illustrator | John Tenniel |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Children's fiction |

| Publisher | Macmillan |

Publication date | 1871 |

| Preceded by | Alice's Adventures in Wonderland |

Through the Looking-Glass, and What Alice Found There (1871) is a novel by Lewis Carroll (Charles Lutwidge Dodgson), the sequel to Alice's Adventures in Wonderland (1865). Set some six months later than the earlier book, Alice again enters a fantastical world, this time by climbing through a mirror into the world that she can see beyond it. Through the Looking-Glass includes such celebrated verses as "Jabberwocky" and "The Walrus and the Carpenter", and the episode involving Tweedledum and Tweedledee. The mirror which inspired Carroll remains displayed in Charlton Kings.

Plot summary

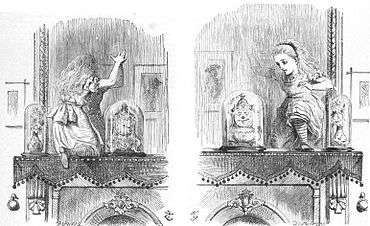

Chapter One – Looking-Glass House: Alice is playing with a white kitten (whom she calls "Snowdrop") and a black kitten (whom she calls "Kitty")—the offspring of Dinah, Alice's cat in Alice's Adventures in Wonderland—when she ponders what the world is like on the other side of a mirror's reflection. Climbing up on the fireplace mantel, she pokes at the wall-hung mirror behind the fireplace and discovers, to her surprise, that she is able to step through it to an alternative world. In this reflected version of her own house, she finds a book with looking-glass poetry, "Jabberwocky", whose reversed printing she can read only by holding it up to the mirror. She also observes that the chess pieces have come to life, though they remain small enough for her to pick up.

Chapter Two – The Garden of Live Flowers: Upon leaving the house (where it had been a cold, snowy night), she enters a sunny spring garden where the flowers have the power of human speech; they perceive Alice as being a "flower that can move about." Elsewhere in the garden, Alice meets the Red Queen, who is now human-sized, and who impresses Alice with her ability to run at breathtaking speeds. This is a reference to the chess rule that queens are able to move any number of vacant squares at once, in any direction, which makes them the most "agile" of pieces.

Chapter Three – Looking-Glass Insects: The Red Queen reveals to Alice that the entire countryside is laid out in squares, like a gigantic chessboard, and offers to make Alice a queen if she can move all the way to the eighth rank/row in a chess match. This is a reference to the chess rule of Promotion. Alice is placed in the second rank as one of the White Queen's pawns, and begins her journey across the chessboard by boarding a train that literally jumps over the third row and directly into the fourth rank, thus acting on the rule that pawns can advance two spaces on their first move.

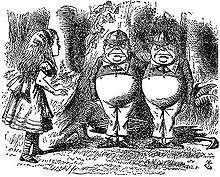

Chapter Four – Tweedledum and Tweedledee: She then meets the fat twin brothers Tweedledum and Tweedledee, whom she knows from the famous nursery rhyme. After reciting the long poem "The Walrus and the Carpenter", the Tweedles draw Alice's attention to the Red King—loudly snoring away under a nearby tree—and maliciously provoke her with idle philosophical banter that she exists only as an imaginary figure in the Red King's dreams (thereby implying that she will cease to exist the instant he wakes up). Finally, the brothers begin acting out their nursery-rhyme by suiting up for battle, only to be frightened away by an enormous crow, as the nursery rhyme about them predicts.

Chapter Five – Wool and Water: Alice next meets the White Queen, who is very absent-minded but boasts of (and demonstrates) her ability to remember future events before they have happened. Alice and the White Queen advance into the chessboard's fifth rank by crossing over a brook together, but at the very moment of the crossing, the Queen transforms into a talking Sheep in a small shop. Alice soon finds herself struggling to handle the oars of a small rowboat, where the Sheep annoys her with (seemingly) nonsensical shouting about "crabs" and "feathers". Unknown to Alice, these are standard terms in the jargon of rowing. Thus (for a change) the Queen/Sheep was speaking in a perfectly logical and meaningful way.

Chapter Six – Humpty Dumpty: After crossing yet another brook into the sixth rank, Alice immediately encounters Humpty Dumpty, who, besides celebrating his unbirthday, provides his own translation of the strange terms in "Jabberwocky". In the process, he introduces Alice (and the reader) to the concept of portmanteau words, before his inevitable fall.

Chapter Seven – The Lion and the Unicorn: "All the king's horses and all the king's men" come to Humpty Dumpty's assistance, and are accompanied by the White King, along with the Lion and the Unicorn, who again proceed to act out a nursery rhyme by fighting with each other. In this chapter, the March Hare and Hatter of the first book make a brief re-appearance in the guise of "Anglo-Saxon messengers" called "Haigha" and "Hatta" (i.e. "Hare" and "Hatter"—these names are the only hint given as to their identities other than John Tenniel's illustrations).

Chapter Eight – “It’s my own Invention”: Upon leaving the Lion and Unicorn to their fight, Alice reaches the seventh rank by crossing another brook into the forested territory of the Red Knight, who is intent on capturing the "white pawn"—who is Alice—until the White Knight comes to her rescue. Escorting her through the forest towards the final brook-crossing, the Knight recites a long poem of his own composition called Haddocks' Eyes, and repeatedly falls off his horse. His clumsiness is a reference to the "eccentric" L-shaped movements of chess knights, and may also be interpreted as a self-deprecating joke about Lewis Carroll's own physical awkwardness and stammering in real life.

Chapter Nine – Queen Alice: Bidding farewell to the White Knight, Alice steps across the last brook, and is automatically crowned a queen, with the crown materialising abruptly on her head. She soon finds herself in the company of both the White and Red Queens, who relentlessly confound Alice by using word play to thwart her attempts at logical discussion. They then invite one another to a party that will be hosted by the newly crowned Alice—of which Alice herself had no prior knowledge.

Chapter Ten – Shaking: Alice arrives and seats herself at her own party, which quickly turns to a chaotic uproar—much like the ending of the first book. Alice finally grabs the Red Queen, believing her to be responsible for all the day's nonsense, and begins shaking her violently with all her might. By thus "capturing" the Red Queen, Alice unknowingly puts the Red King (who has remained stationary throughout the book) into checkmate, and thus is allowed to wake up.

Chapter Eleven – Waking: Alice suddenly awakes in her armchair to find herself holding the black kitten, whom she deduces to have been the Red Queen all along, with the white kitten having been the White Queen.

Chapter Twelve – Which dreamed it?: The story ends with Alice recalling the speculation of the Tweedle brothers, that everything may have, in fact, been a dream of the Red King, and that Alice might herself be no more than a figment of his imagination. One final poem is inserted by the author as a sort of epilogue which suggests that life itself is but a dream.

Characters

Main characters

- Alice

- Bandersnatch

- Haigha (March Hare)

- Hatta (The Hatter)

- Humpty Dumpty

- The Jabberwock

- Jubjub bird

- Red King

- Red Queen

- The Lion and the Unicorn

- The Sheep

- The Walrus and the Carpenter

- Tweedledum and Tweedledee

- White King

- White Knight

- White Queen

Minor characters

Returning characters

The characters of Hatta and Haigha (pronounced as the English would have said "hatter" and "hare") make an appearance, and are pictured (by Sir John Tenniel, not by Carroll) to resemble their Wonderland counterparts, the Hatter and the March Hare. However, Alice does not recognise them as such.

Dinah, Alice's cat, also makes a return – this time with her two kittens, Kitty (the black one) and Snowdrop (the white one). At the end of the book they are associated with the Red Queen and the White Queen respectively in the looking-glass world.

Though she does not appear, Alice's sister is mentioned. In both Alice's Adventures in Wonderland and Through the Looking-Glass, there are puns and quips about two non-existing characters, Nobody and Somebody. Paradoxically, the gnat calls Alice an old friend, though it was never introduced in Alice's Adventures in Wonderland.

Writing style and themes

Symbolism

The themes and settings of Through the Looking-Glass make it a kind of mirror image of Wonderland: the first book begins outdoors, in the warm month of May (4 May),[lower-alpha 1] uses frequent changes in size as a plot device, and draws on the imagery of playing cards; the second opens indoors on a snowy, wintry night exactly six months later, on 4 November (the day before Guy Fawkes Night),[lower-alpha 2] uses frequent changes in time and spatial directions as a plot device, and draws on the imagery of chess. In it, there are many mirror themes, including opposites, time running backwards, and so on.

The White Queen offers to hire Alice as her lady's maid and to pay her "Twopence a week, and jam every other day." Alice says that she doesn't want any jam today, and the Queen tells her: "You couldn't have it if you did want it. The rule is, jam tomorrow and jam yesterday—but never jam to-day." This is a reference to the rule in Latin that the word iam or jam meaning now in the sense of already or at that time cannot be used to describe now in the present, which is nunc in Latin. Jam is therefore never available today.[1]

Chess

Whereas the first book has the deck of cards as a theme, this book is based on a game of chess, played on a giant chessboard with fields for squares. Most main characters in the story are represented by a chess piece or animals, with Alice herself being a pawn.

The looking-glass world is divided into sections by brooks or streams, with the crossing of each brook usually signifying a notable change in the scene and action of the story: the brooks represent the divisions between squares on the chessboard, and Alice's crossing of them signifies advancing of her piece one square. Furthermore, since the brook-crossings do not always correspond to the beginning and ends of chapters, most editions of the book visually represent the crossings by breaking the text with several lines of asterisks ( * * * ). The sequence of moves (white and red) is not always followed. The most extensive treatment of the chess motif in Carroll's novel is provided in Glen Downey's The Truth About Pawn Promotion: The Development of the Chess Motif in Victorian Fiction.[2]

Poems and songs

|

To the Looking-Glass world it was Alice that said...

Tune for To the Looking-Glass world it was Alice that said... |

| Problems playing this file? See media help. | |

- Prelude ("Child of the pure unclouded brow")

- "Jabberwocky" (seen in the mirror-house; full poem here including readings)

- "Tweedledum and Tweedledee"

- "The Walrus and the Carpenter" (full poem here)

- "Humpty Dumpty"

- "In Winter when the fields are white..."

- "The Lion and the Unicorn"

- "Haddocks' Eyes" / The Aged Aged Man / Ways and Means / A-sitting on a Gate, the song is A-sitting on a Gate, but its other names and callings are placed above.

- "Hush-a-by lady, in Alice's lap..." (Red Queen's lullaby)

- "To the Looking-Glass world it was Alice that said..."

- White Queen's riddle

- "A boat beneath a sunny sky" is the first line of a titleless acrostic poem at the end of the book—the beginning letters of each line, when put together, spell Alice Pleasance Liddell.

The Wasp in a wig

Lewis Carroll decided to suppress a scene involving what was described as "a wasp in a wig" (possibly a play on the commonplace expression "bee in the bonnet"). It has been suggested in a biography by Carroll's nephew, Stuart Dodgson Collingwood, that one of the reasons for this suppression was a suggestion from his illustrator, John Tenniel,[3] who wrote in a letter to Carroll dated 1 June 1870:

...I am bound to say that the 'wasp' chapter doesn't interest me in the least, and I can't see my way to a picture. If you want to shorten the book, I can't help thinking – with all submission – that there is your opportunity.[4]

For many years no one had any idea what this missing section was or whether it had survived. In 1974, a document purporting to be the galley proofs of the missing section was sold at Sotheby's; the catalogue description read, in part, that "The proofs were bought at the sale of the author's ... personal effects ... Oxford, 1898...". The bid was won by John Fleming, a Manhattan book dealer. The winning bid was £1,700. The contents were subsequently published in Martin Gardner's The Annotated Alice: The Definitive Edition, and is also available as a hardback book The Wasp in a Wig: A Suppressed Episode ....[5]

The rediscovered section describes Alice's encounter with a wasp wearing a yellow wig, and includes a full previously unpublished poem. If included in the book, it would have followed, or been included at the end of, Chapter 8 – the chapter featuring the encounter with the White Knight. The discovery is generally accepted as genuine, but the proofs have yet to receive any physical examination to establish age and authenticity.

Dramatic adaptations

The book has been adapted several times, in combination with Alice's Adventures in Wonderland and as a stand-alone film or television special.

Stand-alone versions

The adaptations include live, TV musicals, live action and animated versions and radio adaptations. One of the earliest adaptations was a silent movie directed by Walter Lang, Alice Through a Looking Glass, in 1928.[6]

A dramatised version directed by Douglas Cleverdon and starring Jane Asher was recorded in the late 1950s by Argo Records, with actors Tony Church, Norman Shelley and Carleton Hobbs, and Margaretta Scott as the narrator.[7]

Musical versions include the 1966 TV musical with songs by Moose Charlap, and Judi Rolin in the role of Alice,[8][9] a Christmas 2007 multimedia stage adaptation at The Tobacco Factory directed and conceived by Andy Burden, written by Hattie Naylor, music and lyrics by Paul Dodgson and a 2008 opera Through the Looking Glass by Alan John.

Television versions include the 1973 BBC TV movie, Alice Through the Looking Glass, with Sarah Sutton playing Alice,[10] a 1982 38-minute Soviet cutout-animated film made by Kievnauchfilm studio and directed by Yefrem Pruzhanskiy,[11] an animated TV movie in 1987, with Janet Waldo as the voice of Alice (Mr. T was the voice of the Jabberwock)[12] and the 1998 Channel 4 TV movie, with Kate Beckinsale playing the role of Alice. This production restored the lost "Wasp in a Wig" episode.[13]

In March 2011, Japanese companies Toei and Banpresto announced that a collaborative animation project based on Through the Looking-Glass tenatively titled Kyōsō Giga (京騒戯画)[14] was in production.

On 22 December 2011, BBC Radio 4 broadcast an adaptation by Stephen Wyatt on Saturday Drama[15] with Lauren Mote as Alice, Julian Rhind-Tutt as Lewis Carroll (who not only narrates the story but is also an active character), Carole Boyd as the Red Queen, Sally Phillips as the White Queen, Nicholas Parsons as Humpty-Dumpty, Alistair McGowan as Tweedledum and Tweedledee and John Rowe as the White Knight.

With Alice's Adventures in Wonderland

Adaptations combined with Alice's Adventures in Wonderland include the 1933 live-action movie Alice in Wonderland, starring a huge all-star cast and Charlotte Henry in the role of Alice. It featured most of the elements from Through the Looking Glass as well, including W. C. Fields as Humpty Dumpty, and a Harman-Ising animated version of The Walrus and the Carpenter.[16] The 1951 animated Disney movie Alice in Wonderland also features several elements from Through the Looking-Glass, including the talking flowers, Tweedledee and Tweedledum, and "The Walrus and the Carpenter".[17] Another adaptation, Alice's Adventures in Wonderland, produced by Joseph Shaftel Productions in 1972 with Fiona Fullerton as Alice, included the twins Fred and Frank Cox as Tweedledum and Tweedledee.[18] The 2010 film Alice in Wonderland by Tim Burton contains elements of both Alice's Adventures in Wonderland and Through the Looking-Glass.[19]

The 1974 Italian TV series Nel Mondo Di Alice (In the World of Alice) which covers both novels, covers Through the Looking-Glass in episodes 3 and 4.[20]

Combined stage productions include the 1980 version, produced and written by Elizabeth Swados, Alice in Concert (aka Alice at the Palace), performed on a bare stage. Meryl Streep played the role of Alice, with additional supporting cast by Mark Linn-Baker and Betty Aberlin. In 2007, Chicago-based Lookingglass Theater Company debuted an acrobatic interpretation of Alice's Adventures in Wonderland and Through the Looking Glass with Lookingglass Alice.[21] Lookingglass Alice was performed in New York City, Philadelphia, Chicago,[22] and in a version of the show which toured the United States.

Iris Theatre in London, England, had a 2 part version of both novels in which Through the Looking-Glass was part 2. Alice was played in both parts by Laura Wickham. It was staged in the summer of 2013.[23]

Laura Wade's Alice, a modern adaptation of both books premiering at the Crucible Theatre in Sheffield in 2010, adapted parts of both novels.

Wonder.land by Moira Buffini and Damon Albarn takes some characters from the second novel, notably Dum and Dee and Humpty Dumpty. The show also merges the Queen of Hearts and the Red Queen into one character.

Adrian Mitchell's Alice in Wonderland and Through the Looking-Glass adaptation for the RSC (Royal Shakespeare Company) adapted through the Looking-Glass in act 2.[24]

The 1985 two-part TV musical Alice in Wonderland, produced by Irwin Allen, covers both books; Alice was played by Natalie Gregory. In this adaptation, the Jabberwock materialises into reality after Alice reads "Jabberwocky", and pursues her through the second half of the musical.[25] The 1999 made-for-TV Hallmark/NBC film Alice in Wonderland, with Tina Majorino as Alice, merges elements from Through the Looking Glass including the talking flowers, Tweedledee and Tweedledum, "The Walrus and the Carpenter", and the chess theme including the snoring Red King and White Knight.[26] The 2009 Syfy TV miniseries Alice contains elements from Alice's Adventures in Wonderland and Through the Looking-Glass.[27]

Other

- The 1977 film Jabberwocky expands the story of the poem "Jabberwocky".[28]

- The 1936 Mickey Mouse short film Thru the Mirror has Mickey travel through his mirror and into a bizarre world.

- The 1959 film Donald in Mathmagic Land includes a segment with Donald Duck dressed as Alice meeting the Red Queen on a chessboard.

- The 2011 ballet Through the Looking-Glass by American composer John Craton

- 2013 book (Through the Zombie Glass) by Gena Showalter

- The 2016 film Alice Through the Looking Glass by James Bobin, a sequel to the 2010 film Alice in Wonderland.

See also

References

Notes

- ↑ In Chapter 7, "A Mad Tea-Party", Alice reveals that the date is "the fourth" and that the month is "May."

- ↑ In the first chapter, Alice speaks of the snow outside and the "bonfire" that "the boys" are building for a celebration "to-morrow", a clear reference to the traditional bonfires on Guy Fawkes Night, 5 November; in the fifth chapter, she affirms that her age is "seven and a half exactly."

Citations

- ↑ Cook, Eleanor (2006). Enigmas and Riddles in Literature. Cambridge University Press. p. 163. ISBN 0521855101.

- ↑ http://www.nlc-bnc.ca/obj/s4/f2/dsk2/tape15/PQDD_0006/NQ34258.pdf

- ↑ Symon, Evan V. (January 14, 2013). "10 Deleted Chapters that Transformed Famous Books". listverse.com.

- ↑ Gardner, Martin (2000). The Annotated Alice. W. W. Norton & Company. p. 283. ISBN 0-393-04847-0.

- ↑ (Clarkson Potter, MacMillan & Co.; 1977)

- ↑ Alice Through a Looking Glass (1928) at the Internet Movie Database

- ↑ "Alice in Wonderland: Wired for Sound". Retrieved 15 November 2009.

- ↑ "ALICE THROUGH THE LOOKING GLASS (1966, U.S.)". Kiddiematinee.com. 6 November 1966. Retrieved 16 January 2012.

- ↑ Alice Through the Looking Glass (1966) at the Internet Movie Database

- ↑ Alice Through the Looking Glass (1973) at the Internet Movie Database

- ↑ "Russian animation in letters and figures | Films | "ALICE IN THE LAND IN THE OTHER SIDE OF THE MIRROR"". Animator.ru. Retrieved 16 January 2012.

- ↑ Alice Through the Looking Glass (1987) at the Internet Movie Database

- ↑ Alice Through the Looking Glass (1998) at the Internet Movie Database

- ↑ "Kyousogiga.com". Kyousogiga.com. Retrieved 5 November 2011.

- ↑ http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b01pf5d7

- ↑ Alice in Wonderland (1933) at the Internet Movie Database

- ↑ Alice in Wonderland (1951) at the Internet Movie Database

- ↑ Alice's Adventures in Wonderland (1972) at the Internet Movie Database

- ↑ Alice in Wonderland (2010) at the Internet Movie Database

- ↑ fictionrare2 (2014-09-29), Nel mondo di Alice 3^p, retrieved 2016-04-23

- ↑ "Lookingglass Alice | Lookingglass Theatre Company". Lookingglasstheatre.org. 13 February 2007. Retrieved 16 January 2012.

- ↑ "Lookingglass Alice Video Preview". Lookingglasstheatre.org. Retrieved 5 November 2011.

- ↑ "Theatre adaptations (excluding reimaginings)". all-in-the-golden-afternoon96.tumblr.com. Retrieved 2016-04-23.

- ↑ "Theatre adaptations (excluding reimaginings)". all-in-the-golden-afternoon96.tumblr.com. Retrieved 2016-04-23.

- ↑ Alice in Wonderland (1985) at the Internet Movie Database

- ↑ Alice in Wonderland (1999) at the Internet Movie Database

- ↑ Alice (2009) at the Internet Movie Database

- ↑ Jabberwocky (1977) at the Internet Movie Database

Other sources

- Tymn, Marshall B.; Kenneth J. Zahorski and Robert H. Boyer (1979). Fantasy Literature: A Core Collection and Reference Guide. New York: R.R. Bowker Co. p. 61. ISBN 0-8352-1431-1.

- Gardner, Martin (1990). More Annotated Alice. New York: Random House. p. 363. ISBN 0-394-58571-2.

- Gardner, Martin (1960). The Annotated Alice. New York: Clarkson N. Potter. pp. 180–181.

External links

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Through the Looking-Glass |

![]() Media related to Through the Looking-Glass and What Alice Found There at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Through the Looking-Glass and What Alice Found There at Wikimedia Commons

- Online texts

- Through the Looking-Glass by Lewis Carroll ePub, Mobi, PDF versions

- Through the Looking-Glass at Project Gutenberg

-

Through the Looking-Glass public domain audiobook at LibriVox

Through the Looking-Glass public domain audiobook at LibriVox - HTML version with commentary of Sabian religion

- Text of A Wasp in a Wig

- c1917 edition from archive.org – scanned for download or reading online

- Multiple Formats ( html, XML, opendocument ODF, pdf (landscape, portrait), plaintext, concordance ) SiSU