The Little Lost Child

| "The Little Lost Child" | |

|---|---|

| Published by Joseph W. Stern & Co. | |

Sheet music cover page | |

| Song | |

| Published | 1894 |

| Form | Sheet music |

| Composer(s) | Joseph W. Stern |

| Lyricist(s) | Edward B. Marks |

| Language | English |

The Little Lost Child is a popular song of 1894 by Edward B. Marks and Joseph W. Stern which sold more than two million copies of its sheet music following its promotion as the first ever illustrated song, an early precursor to the music video.[2][3][4][5] The song was also known by its first three words: "A Passing Policeman."[6] The song's success has also been credited to its performance with enthusiasm by Lottie Gilson[7] and Della Fox.[8]

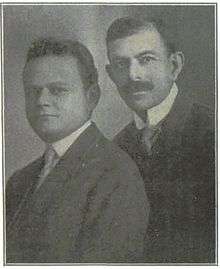

Marks was a button salesman who wrote rhymes and verse, and Stern a necktie salesman who played the piano and wrote tunes. Together they formed a music publishing house called Joseph W. Stern & Co. and became an important part of the Tin Pan Alley sheet music publishing scene.[1][2][3][9] Marks wrote the lyrics about a lost little girl found by a policeman, who goes on to find the girl's mother, who turns out to be the policeman's estranged wife; Stern wrote the music for piano and vocals. Joseph W. Stern & Co. "started their career in a little basement at 314 East Fourteenth Street with a 30-cent sign and a $1 letter box, which to say the least was not large capital even in those days..."[1]

The promoting innovation that made "The Little Lost Child" significant to cultural history was an idea in the mind of George H. Thomas even earlier, in 1892. A production of The Old Homestead at Brooklyn's Amphion Theater, where Thomas was chief electrician, featured the song "Where Is My Wandering Boy Tonight?" illustrated by a single slide of a young man in a saloon. Thomas's idea was to combine a series of images (using a stereopticon) to show a narrative while it was being sung. He approached Stern and Marks about illustrating "The Little Lost Child."[10] Lyrics appeared toward the bottom of the images. The first performance went poorly due to upside-down images of inappropriate size and placement, but these technical difficulties were soon corrected. The illustrated song technique proved so enduring it was still being used to sell songs before movies and during reel changes in movie theaters as recently as 1937 when some color movies had already begun to appear.[10]

Stern retired in 1920, and his firm became the Edward B. Marks Music Company, which published a string of hits such as "Strange Fruit" by Abel Meeropol (and made famous by Billie Holiday) in 1939 and has been a subsidiary of Carlin America since 1980.[8]

"The Little Lost Child" was the first of several hit songs Marks and Stern wrote together as well as the first of several their company published, but it became a true sensation and was well-remembered several decades later.[1] Billboard magazine noted the song's importance in their "honor roll" in 1949.[11]

Lyrics and sheet music

The song's composition employed a strophic form with a chorus. The sentimental lyrics comprised a narrative set to music, a new style in the 1890s.[12]

First verse:

A passing policeman found a little child,

She walked beside him, dried her tears and smiled.

Said he to her kindly now you must not cry,

I will find your ma-ma for you bye and bye.

At the station when he asked her for her name,

And she answered Jennie, it made him exclaim:

"At last of your mother, I have now a trace,

Your little features bring back her sweet face."

Chorus:

Do not fear, my little darling, and I will take you home.

Come sit down close beside me, no more from me you shall roam.

For you were a babe in arms, when your mother left me one day.

Left me at home, deserted, alone, and took you, my child, away.[1]

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

The_Little_Lost_Childwas invoked but never defined (see the help page).

References

- 1 2 3 4 "Joseph W. Stern & Co. Celebrate 25th anniversary". The Music Trade Review: 48. 1919.

- 1 2 Altman, Rick (2007). Silent Film Sound. Columbia University Press. pp. 107/462. ISBN 0231116632.

- 1 2 Kohn, Al; Kohn, Bob (2002). Kohn On Music Licensing, 3rd Edition. Aspen Publishers. pp. 141(1636). ISBN 0-7355-1447-X.

- ↑ Marks, Edward B.; A.J. Liebling (1934). They All Sang: from Tony Pastor to Rudy Vallee. The Viking Press. p. 321. ASIN B000SKUALG.

- ↑ "Music Video 1900 Style". PBS. 2004.

- ↑ "Birthplace of Country Music: Our Musical Heritage:1927 Bristol Sessions". Smithsonian Institution.

- ↑ Marks, Edward B.; Joseph W. Stern (1894). The Little Lost Child. Jos. W. Stern & Co. pp. 1–5.

- 1 2 Jasen, David A. (2003). Tin Pan Alley encyclopedia of the golden age of American song. Routledge. pp. 270–1/475. ISBN 0-415-93877-5.

- ↑ Goldberg, Isaac; Gershwin, George (1930). Tin Pan Alley: A Chronicle of the American Popular Music Racket. Kessinger Publishing, LLC. pp. 141(376). ISBN 978-1417904532.

- 1 2 Witmark, Isidore; Goldberg, Isaac (1939). The House of Witmark. New York: New York OOO. p. 116. ASIN B001DZ8MP6.

- ↑ Gussie Davis (1949). "The Honor Roll of Popular Songwriters No. 24". Billboard. 61 (24): 38.

- ↑ "1860-1900 Popular Songs". Special Collections at the Sheridans Libraries. Johns Hopkins University. Retrieved 2009-12-22.

External links

- Tear Jerkers of the Not-So-Gay Nineties Treasure LP-408 (196?) track 6 George Jessel

- Bristol Sessions. Vol 2, Country Music Foundation (1927) track 22:A Passing Policeman Johnson Brothers

- Music Video 1900 style videos of other early illustrated songs on "PBS Kids Go!"