The Ecstatic

| The Ecstatic | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Studio album by Mos Def | ||||

| Released | June 9, 2009 | |||

| Studio | Record Plant and Someothaship Connect in Los Angeles; Downtown Music Studios in New York City; Hovercraft Studios in Virginia Beach | |||

| Genre | Conscious rap, alternative hip hop | |||

| Length | 45:34 | |||

| Label | Downtown | |||

| Producer | Georgia Anne Muldrow, J Dilla, Madlib, Mos Def, Mr. Flash, The Neptunes, Oh No, Preservation | |||

| Mos Def chronology | ||||

| ||||

| Singles from The Ecstatic | ||||

|

||||

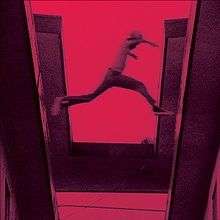

The Ecstatic is the fourth studio album by American rapper Mos Def. After venturing further away from hip hop with an acting career and two poorly received albums, Mos Def signed with Downtown Records and recorded The Ecstatic primarily at the Record Plant in Los Angeles. He worked with producers such as Preservation, Mr. Flash, Oh No, and Madlib, the latter two of whom reused instrumentals they had produced on Stones Throw Records. Singer Georgia Anne Muldrow, formerly of the record label, was one of the album's few guest vocalists, along with rappers Slick Rick and Talib Kweli. For its front cover, a still from Charles Burnett's 1978 film Killer of Sheep was reproduced in red tint.

The Ecstatic was described by music journalists as a conscious and alternative hip hop record with an eccentric, internationalist quality. Mos Def's raps about global politics, love, spirituality, and social conditions were informed by the zeitgeist of the late 2000s, Black internalionalism, and Pan-Islamic ideas, as he incorporated a number of Islamic references throughout the album. Its loosely structured, lightly reverbed songs used unconventional time signatures and samples taken from a variety of international musical styles, including Afrobeat, soul, Eurodance, jazz, reggae, Latin, and Middle Eastern music. Mos Def titled The Ecstatic after one of his favorite novels—the 2002 Victor LaValle book of the same name—believing its titular phrase evoked his singular creative vision for the album.

Released on June 9, 2009, The Ecstatic charted at number nine on the Billboard 200 and eventually sold 168,000 copies. Its sales benefited from its presence on Internet blogs and the release of a T-shirt illustrating the record's packaging alongside a label printed with a code redeemable for a free download of the album. A widespread critical success, The Ecstatic was viewed as a return to form for Mos Def and one of the year's best albums. He embarked on an international tour to support the record, performing concerts in North America, Japan, Australia, and the United Kingdom between September and April 2010. While touring with him as his DJ, Preservation began to develop remixes of the album's songs, which he later released on the remix album The REcstatic in 2013.

Recording and production

.jpg)

In 2006, Mos Def's third album True Magic was released haphazardly by Geffen Records to fulfill a contractual obligation while he was devoting more time to his acting career.[1] The quality of the album, along with his repeated ventures away from hip hop in his music, left "some fans wondering if Mos Def's acting accomplishments were finally affecting his music", PopMatters critic Quentin B. Huff later wrote.[2] After ending his tenure on Geffen, he signed a record deal with Downtown Records and recorded The Ecstatic as his first album for the label.[3] Most of its songs were recorded in sessions that took place at the Record Plant in Los Angeles; the songs "Twilight Speedball", "No Hay Nada Mas", and "Roses" were partially recorded at Hovercraft Studios in Virginia Beach, Someothaship Connect in Los Angeles, and New York City's Downtown Music Studios.[4]

Mos Def worked with producers Mr. Flash, Oh No, Madlib, and Preservation, who previously produced some of True Magic's songs. For The Ecstatic, Oh No reused some of his productions from his 2007 album Dr. No's Oxperiment, while Madlib incorporated samples from his Beat Konducta in India (2007) record. For "Life in Marvelous Times", Mr. Flash reused the beat from "Champions"—his 2006 collaboration with the French hip hop group TTC—while "History" used a beat produced by J Dilla before his death.[5] With Preservation, Mos Def produced "Casa Bey" after a 2006 trip to Rio de Janeiro, where local rapper MV Bill introduced him to the music of Banda Black Rio. Mos Def and Preservation altered one of the band's songs—"Casa Forte", an instrumental featuring their characteristic blend of funk, jazz, soul, and Brazilian rhythms—and used it as the beat.[6] The original song title—meaning "strong house" in Portuguese—was changed to "Casa Bey"; Bey was Mos Def's family surname. According to him, he tried to enlist rappers Jay Electronica, Black Thought, and Trugoy for the song, but they all found it too difficult to rap over the instrumental.[7]

Mos Def collaborated with singer Georgia Anne Muldrow and rappers Slick Rick and Talib Kweli—his partner in the rap duo Black Star.[8] Muldrow sang and played piano on "Roses", which she originally wrote and recorded in 2008 for her album Umsindo (2009). She said Mos Def "borrowed" the song for The Ecstatic after they met through a mutual friend. "They came over one day and started playing 'Roses.' He was singing the song and knew it. He said 'I wanna grab that.' I said, 'Man, I already got this as a single'. He just wanted that song. He snatched it up real quick", she recalled in laughter.[9] Along with Madlib, Oh No, and J Dilla, Muldrow had been an affiliate of Stones Throw Records; according to journalist Nathan Rabin, they collectively produced half of the album, giving its sound a "sympathetic" quality.[10] With The Ecstatic, Mos Def said he wanted to offer listeners sincere, uninhibited observations about life and love, "some truth and positive heart lift", without the need for club songs. "No disrespect to [the club]".[11]

Music and lyrics

|

"Auditorium"

On "Auditorium", Mos Def rapped about daily struggles and global politics over a Middle Eastern-influenced instrumental produced by Madlib.[12] |

| Problems playing this file? See media help. | |

The music on The Ecstatic covered an international range of styles in a very loose and extemporaneous manner, held together by "a lyrical and sonic fascination with life beyond the Western World", Rabin wrote in The A.V. Club.[13] According to Robert Christgau, the album's songs generally averaged two-and-a-half minutes and segued into one another without resolution, giving it the feel of a globally influenced hip hop mixtape, "with poles in Brooklyn and Beirut".[14] The record reflected Mos Def's varied interests in jazz, poetry, Eastern rhythms, psychedelia, Spanish music, and the blues.[15] The tracks on the first half, The Observer's Ben Thompson wrote, were "predominantly eastward-looking" while the second half indulged more in Latin and reggae influences.[16] Other sounds sampled or explored included Afrobeat ("Quiet Dog Bite Hard"), Eurodance ("Life in Marvelous Times"), Bollywood ("Supermagic"), and Philadelphia soul.[17] "Supermagic" also drew on elements from Turkish acid rock and Mary Poppins, while on "No Hay Nada Mas", Mos Def sang and rapped in Spanish over a flamenco-influenced production.[18] He sang elsewhere on the album, often breaking into sing-song vamps during his raps.[19] Along with Mos Def's singing, the predominantly sample-based music was unconventional in its use of what Preservation said were unusual time signatures and "awkward" breakdowns.[20]

"You're living at a time of extremism, a time of revolution, a time when there's got to be a change. People in power have misused it. And now there has to be a change and a better world has to be built and the only way it's going to be built is with extreme methods. And I, for one, will join in with anyone. I don't care what color you are, as long as you want to change this miserable condition that exists on this earth. Thank you."

—1964 Malcolm X speech sampled for the beginning of the album[21]

According to The Independent's Simmy Richman, The Ecstatic's Eastern-influenced musical backdrop was reflective of Mos Def's "post-War on Terror" themes; Richman considered it to be a conscious rap record, and No Ripcord's Ryan Faughnder characterized its music as "socially conscious alternative hip-hop".[22] Mos Def incorporated a number of Islamic references onto the album, including samples of American Muslim activist Malcolm X, Turkish protest singer Selda Bağcan, and an Arab-language scene from the 1966 film The Battle of Algiers; additionally, the track "Wahid" was titled after the Arabic word for "oneness". African-American studies and media scholar Sohail Daulatzai believed The Ecstatic was informed by Black internationalist politics and Pan-Islamic ideas, while State magazine's Niall Byrne said it explored the theme of international relations on songs such as the Middle Eastern-influenced "The Embassy" and "Auditorium", which featured an Iraq-themed guest rap by Slick Rick.[23] On the former track, Mos Def rapped from the perspective of an outsider about the lifestyle of an ambassador at a luxury hotel, while the opening song "Supermagic" critiqued government treatment of minority groups.[24]

As on Mos Def's other albums, he spoke a dedication to God in Arabic ("Bismillah ar-Rahman ar-Raheem") at the start of The Ecstatic, before "Supermagic" began with a sample of Malcolm X's 1964 speech at Oxford Union.[25] The sample prefaced the album's "small-globe statement", Pitchfork journalist Nate Patrin explained, indicating that Mos Def had "a stake in something greater than just one corner of the rap world".[5] Alex Young from Consequence of Sound believed the speech introduced "a political album encompassing global beats and viewpoints".[26] According to Washington Post critic Allison Stewart, Mos Def seemed equally interested in the Obama-era zeitgeist and accounts of the past, such as the early-1980s Bedford–Stuyvesant setting of "Life in Marvelous Times".[15] Young deemed the song anthemic for "a seemingly paradoxical age that routinely sees events such as a Black man being elected president of a nation wallowing in racial inequality".[26] From Christgau's perspective, Mos Def offered a credo in the lyrics: "More of less than ever before / It's just too much more for your mind to absorb / It's scary like hell, but there's no doubt / We can't be alive in no time but now".[14]

Throughout The Ecstatic, Mos Def alternated between what AllMusic's Andy Kellman called nonsensical yet intellectual raps and "seemingly nonchalant, off-the-cuff boasts", set against eccentric, lightly reverbed productions.[27] According to The Guardian's Paul MacInnes, The Ecstatic featured his characteristically "fragmented lyrical style, which looped words within phrases and played on sound as much as meaning".[28] "Auditorium" showcased his "complex and convoluted" lyricism delivered closely in rhythm with the beat, Patrin said, citing the lines "soul is the lion's roar, voice is the siren / I swing 'round, wring out and bring down the tyrant / chop a small axe and knock a giant lopsided".[5] He explored Afrocentric themes on "Revelations" and compared love to a gunfight on "Pistola". On "Roses", Muldrow sang nature-friendly lyrics about drawing flowers in times of sadness rather than plucking them from the ground. "Roses is about creativity and human capacity", she explained. "A lot of times Western society makes [women] base our sense of worth on 'diamonds are forever' or 'a dozen roses' and that's how you prove your love to somebody ... but you receive so many gifts and still feel empty. So draw them and let the roses come from inside."[9]

Title and packaging

The Ecstatic was titled after Victor LaValle's 2002 dark humor novel of the same name.[29] One of Mos Def's favorite novels, it was written about an overweight college dropout who fell into mental illness while living with his eccentric family in Queens, New York.[30] According to Mos Def, the phrase "the ecstatic" was "used in the 17th and 18th centuries to describe people who were either mad or divinely inspired and consequently dismissed as kooks".[29] The phrase resonated with him, as he believed no one else in hip hop had ever recorded an album like The Ecstatic. "I feel like I was the only person who was capable of making this type of music in this type of way", he claimed. "I don't rap like nobody, I don't try to sound like nobody."[31] He said "the ecstatic" also referred to "a type of devotional energy, an impossible dream that becomes reality but is discredited before it's realized. The airplane, a nutty idea. The telephone, the Internet. People who envisioned those were considered radical or extreme."[29]

The Ecstatic was packaged with few liner notes and a two-sheet booklet featuring a photo of Mos Def taken using the Photo Booth software application.[32] The front cover photo reproduced a still in red tint from Killer of Sheep, a low-budget 1978 film by Charles Burnett about African-American life in 1970s Watts, Los Angeles.[33] According to Dale Eisinger from Complex, the "subtle and still-moving" front cover photo reflected the ideas of cultural justice and global inequality present throughout Mos Def's career while capturing the "sonic construction" of The Ecstatic's music. "The cover has hazy, dream-like movement", Eisinger said, "appearing as a non-narrative, loose collection of vignettes that are tangentially fascinating and incredibly powerful."[34] For the back cover, a 1928 photo of the Moorish Science Temple gathering in Chicago was used, which Daulatzai interpreted as another element of Mos Def's "Pan-Islamic mashup" on the album.[23]

Release and reception

| Professional ratings | |

|---|---|

| Review scores | |

| Source | Rating |

| AllMusic | |

| Entertainment Weekly | B+[35] |

| The Guardian | |

| The Irish Times | |

| MSN Music | A[14] |

| Pitchfork | 8/10[5] |

| Rolling Stone | |

| Spin | 9/10[38] |

| The Times | |

| USA Today | |

The Ecstatic was released by Downtown on June 9, 2009.[41] In its first week, the album sold 39,000 copies and debuted at number nine on the Billboard 200, becoming the second record of Mos Def's career to reach the top ten on the chart.[42] The following week, he became the first recording artist to endorse the Original Music Tee, a T-shirt featuring the album cover on the front, the track listing on the back, and a tag with a code to download an MP3 copy of the record.[43] The marketing strategy led to enough sales that Billboard factored the T-shirts as album units on the magazine's music charts.[44] The Ecstatic also benefited from the number of mentions it received on Internet blog posts, which peaked during the week of June 29.[45] The album reached 168,000 copies sold in March 2014.[46]

Three singles were released from The Ecstatic: "Life in Marvelous Times" on November 4, 2008; "Quiet Dog Bite Hard" on January 13, 2009; and "Casa Bey" on May 26.[47] According to Charles Aaron, "Life in Marvelous Times" was the "most powerful and accessible song" Mos Def had ever recorded, but it could not even manage to receive airplay on radio stations in his native New York. "If [it] can't get on the radio, then I don't need to be on the radio", Mos Def said in August, expressing a wavering interest in reaching mainstream audiences.[48] At the month's start, he embarked on the North American leg of The Ecstatic Tour, performing through mid September with Jay Electronica as his opening act and co-headlining certain shows with Kweli and singer Erykah Badu.[49] He toured into the following year, playing a series of concerts in Japan during late 2009, Australia in January 2010, and the United Kingdom in April.[50]

The Ecstatic received widespread acclaim from critics. At Metacritic, which assigns a normalized rating out of 100 to reviews from mainstream publications, the album received an average score of 81, based on 28 reviews.[41] After two poorly received records, The Ecstatic was viewed by critics as a return for Mos Def to the form of his 1999 debut album Black on Both Sides.[2] In Spin magazine, Aaron wrote that the "internationalist return to form" was also "perhaps his liveliest work yet".[38] Mick Middles from The Quietus hailed it as "the joyful sound of a rampant artist, unrestrained by expectation or commercialism", with free-flowing music that escaped the boundaries his previous albums had merely pushed.[51] Thompson believed the diverse range of samples made The Ecstatic "a crate-digger's wet dream" and "a thrillingly accessible demonstration of hip-hop's limitless creative possibilities" to a layperson.[16] Writing in MSN Music, Christgau felt the songs were "devoid of hooks but full of sounds you want to hear again", along with "thoughtfully slurred" yet intelligible lyrics by Mos Def, whose creative vision warranted the introductory Malcolm X sample.[14] Steve Jones of USA Today said his reflections on politics, love, religion, and societal conditions were full of insight and sincerity while calling the album his strongest effort so far.[40] Eric Henderson from Slant Magazine was less impressed, writing that much of the music lacked song structure and "careened wildly, free from the constraints of chorus and verse"; Rolling Stone critic Christian Hoard found the quality of the songs inconsistent.[52]

At the end of 2009, The Ecstatic was named one of the year's best albums; according to Acclaimed Music, it was the 21st most ranked record on critics' year-end lists.[53] The album was ranked 30th by The Guardian, 24th by Q, 23rd by Slant Magazine, 17th by Rolling Stone, 16th by Sputnikmusic, 15th by PopMatters, 12th by Spex, and 7th by Spin; About.com named it the year's best rap record.[54] In The Village Voice's Pazz & Jop—an annual poll of American critics nationwide—The Ecstatic was voted the 11th best album of 2009.[55] Christgau, the poll's creator, ranked it 12th on his own year-end list for The Barnes & Noble Review.[56] The Times placed it at number 30 on the newspaper's decade-end list of the 100 greatest records from the 2000s.[55] It was also nominated for a 2010 Grammy Award in the category of Best Rap Album, while "Casa Bey" was nominated for Best Rap Solo Performance.[57]

While on tour as Mos Def's in-concert DJ, Preservation began to remix some of The Ecstatic's songs for their live routine. He challenged himself to remix the rest of the record, taking more than a year, as a project called The REcstatic, working with Jan Fairchild, the original album's mixing engineer.[58] Preservation revisited sources for the original beats to find similar recordings that would correspond to each song's particular aesthetic while preserving Mos Def's vocals for the remixes.[59] He wanted them to be sample-based and consistent in key, pitch, and tone to the first album, which he found difficult to achieve because of the original music's unorthodox instrumentals and singing. "It's the result of countless hours of digging through records to sample", he recalled. "Constructing the beat, wrapping it around the vocal, adjusting the tempo, and so on".[59] The REcstatic was released as a free download on June 12, 2013, by Preservation's imprint label, Mon Dieu Music.[20] Reviewing the remix album in Tiny Mix Tapes, Samuel Diamond said the rapturous energy of the original record was given a "slightly rougher texture" on what he deemed "a respectful contribution to the canon of remix-based art, something that can be said for very few modern rap 'remixes'".[60]

Track listing

Credits are adapted from Downtown Music.[4]

| No. | Title | Writer(s) | Producer(s) | Length |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Supermagic" | Dante Smith, Michael Jackson | Oh No | 2:32 |

| 2. | "Twilite Speedball" | Smith, Chad Hugo | The Neptunes, Mos Def | 3:02 |

| 3. | "Auditorium" (featuring Slick Rick) | Smith, Otis Jackson Jr., Richard Walters | Madlib, Mos Def | 4:34 |

| 4. | "Wahid" | Smith, O. Jackson | Madlib | 1:39 |

| 5. | "Priority" | Smith, Jean Daval | Preservation | 1:22 |

| 6. | "Quiet Dog Bite Hard" | Smith, Daval | Preservation | 2:57 |

| 7. | "Life in Marvelous Times" | Smith, Gilles Bousquet | Mr. Flash | 3:41 |

| 8. | "The Embassy" | Smith, Bousquet, Ihsan al Munzer | Mr. Flash, Mos Def | 2:45 |

| 9. | "No Hay Nada Mas" | Smith, Daval | Preservation | 1:42 |

| 10. | "Pistola" | Smith, M. Jackson, Anthony Hester | Oh No | 3:02 |

| 11. | "Pretty Dancer" | Smith, O. Jackson | Madlib | 3:31 |

| 12. | "Workers Comp." | Smith, Bousquet, Marvin Gaye | Mr. Flash | 2:02 |

| 13. | "Revelations" | Smith, O. Jackson, Michael Drake | Madlib | 2:03 |

| 14. | "Roses" (featuring Georgia Anne Muldrow) | Smith, Georgia Anne Muldrow | Georgia Anne Muldrow | 3:41 |

| 15. | "History" (featuring Talib Kweli) | Smith, James Yancey, Talib K. Greene, Zekkariyas, Mary Wells Womack | J Dilla | 2:21 |

| 16. | "Casa Bey" | Smith, Eduardo Lobo | Preservation, Mos Def[6] | 4:32 |

Sample credits

- "Supermagic" contains a sample of "Ince Ince" by Selda Bağcan.

- "Priority" contains elements from "Flower" by Bobby Hebb.

- "Quiet Dog Bite Hard" contains portions of an interview with Fela Kuti from the documentary film Music Is the Weapon.

- "The Embassy" contains a sample of "The Joy of Lina" by Ihsan al Munzer.

- "Pistola" contains elements from "In the Rain" by Billy Wooten.

- "Workers Comp." contains a sample of "If This World Were Mine" by Marvin Gaye.

- "Revelations" contains portions of "Colours" by Michael Drake.

- "History" contains a sample of "Two Lovers History" by Mary Wells.

- "Casa Bey" contains a sample of "Casa Forte" by Banda Black Rio.

Personnel

Credits are adapted from Downtown Music.[4]

|

|

Charts

| Chart (2009) | Peak position |

|---|---|

| American Albums Chart[27] | 9 |

| American Independent Albums Chart[27] | 2 |

| American R&B/Hip-Hop Albums Chart[27] | 5 |

| American Rap Albums Chart[27] | 2 |

| Canadian Albums Chart[27] | 24 |

| French Albums Chart[61] | 172 |

| Swiss Albums Chart[61] | 90 |

See also

References

- ↑ Samuel 2009; Huff 2009.

- 1 2 Huff 2009.

- ↑ Samuel 2009.

- 1 2 3 Anon.(f) n.d.

- 1 2 3 4 Patrin 2009.

- 1 2 Richard 2009.

- ↑ Anon. 2009a.

- ↑ Anon.(h) n.d.; Jones 2009.

- 1 2 Anon. 2009b.

- ↑ Rabin 2009.

- ↑ Anon. 2009a; Gundersen 2009.

- ↑ Slavik 2009.

- ↑ Patrin 2009; Rabin 2009.

- 1 2 3 4 Christgau 2009.

- 1 2 Stewart 2009.

- 1 2 Thompson 2009.

- ↑ Kot 2009; Patrin 2009; Kellman n.d..

- ↑ Kot 2009; Patrin 2009; Stewart 2009.

- ↑ Kot 2009; Patrin 2009.

- 1 2 Balfour 2013.

- ↑ Anon. 2015.

- ↑ Richman 2009; Faughnder 2009.

- 1 2 Daulatzai 2012, p. 132.

- ↑ Christgau 2009; Byrne 2009; Anon. 2015.

- ↑ Daulatzai 2012, p. 132; St. John 2009; Patrin 2009.

- 1 2 Young 2009.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Kellman n.d.

- 1 2 MacInnes 2009.

- 1 2 3 Gundersen 2009.

- ↑ Samuel 2009; Gundersen 2009.

- ↑ Gundersen 2009; Anon. 2009a.

- ↑ Raible 2009.

- ↑ Patrin 2009; Eisinger 2013.

- ↑ Eisinger 2013.

- ↑ Vozick-Levinson 2009.

- ↑ Carroll 2009.

- ↑ Hoard 2009.

- 1 2 Aaron 2009, p. 80.

- ↑ Potton 2009.

- 1 2 Jones 2009.

- 1 2 Anon.(h) n.d.

- ↑ Anon.(h) n.d.; Caulfield 2009.

- ↑ Michaels 2009.

- ↑ Owsinski 2009, p. 70.

- ↑ Siehndel et al. 2013, p. 279.

- ↑ Baker 2014.

- ↑ Samuel 2008; Anon.(e) n.d.; Anon.(d) n.d..

- ↑ Aaron 2009, p. 78.

- ↑ Dantana 2009.

- ↑ Murray 2010; Maness 2009; Anon. 2010.

- ↑ Middles 2009.

- ↑ Henderson 2009; Hoard 2009.

- ↑ Anon.(c) n.d.

- ↑ Anon.(a) n.d.

- 1 2 Anon.(b) n.d.

- ↑ Christgau 2010.

- ↑ Harling 2009.

- ↑ Balfour 2013; Lamb 2013.

- 1 2 Lamb 2013.

- ↑ Diamond 2013.

- 1 2 Anon.(g) n.d.

Bibliography

- Aaron, Charles (2009). "The SPIN Interview: Mos Def". Spin. Vol. 25 no. 8.

- Anon. (2009a). "House Music: Mos Def". Interview. Archived from the original on June 16, 2016. Retrieved June 13, 2016.

- Anon. (2009b). "Mos Def Clips 'Roses' From Up-And-Coming Singer". The Urban Daily. Archived from the original on June 16, 2016. Retrieved June 4, 2016.

- Anon. (2010). "Mos Def Announces Australian Tour". Triple J. Archived from the original on June 16, 2016. Retrieved June 6, 2016.

- Anon. (2015). "X Gon' Give It To Ya: Five Rap Songs That Shine Light On Malcolm X's Brilliance". Vibe. Archived from the original on June 16, 2016. Retrieved June 4, 2016.

- Anon.[a] (n.d.). "The 100 Best Hip-Hop Albums of the 2000s". About.com. Retrieved June 4, 2016.

- Anon.[b] (n.d.). "The Ecstatic". Acclaimed Music. Archived from the original on June 16, 2016. Retrieved October 4, 2015.

- Anon.[c] (n.d.). "Mos Def". Acclaimed Music. Archived from the original on June 16, 2016. Retrieved October 4, 2015.

- Anon.[d] (n.d.). "Casa Bey – Mos Def". AllMusic. Archived from the original on June 16, 2016. Retrieved June 5, 2016.

- Anon.[e] (n.d.). "Quiet Dog – Mos Def". AllMusic. Archived from the original on June 16, 2016. Retrieved June 4, 2016.

- Anon.[f] (n.d.). "Mos Def – The Ecstatic". Downtown Music. Archived from the original on June 4, 2016. Retrieved June 4, 2016.

- Anon.[g] (n.d.). "Mos Def – The Ecstatic". Hung Medien. Archived from the original on June 16, 2016. Retrieved June 5, 2016.

- Anon.[h] (n.d.). "The Ecstatic Reviews". Metacritic. Archived from the original on June 16, 2016. Retrieved April 21, 2013.

- Baker, Soren (2014). "50 Cent Leaves Interscope: How Nas, Busta Rhymes, Ghostface Killah & Mos Def Fared After Leaving Their Longtime Label Homes". HipHopDX. Archived from the original on June 16, 2016. Retrieved June 4, 2016.

- Balfour, Jay (2013). "Yasiin Bey (Mos Def) & Preservation Release 'The REcstatic' Remix Album". HipHopDX. Archived from the original on June 16, 2016. Retrieved June 13, 2016.

- Byrne, Niall (2009). "Mos Def – The Ecstatic". State. Archived from the original on June 16, 2016. Retrieved June 6, 2016.

- Carroll, Jim (2009). "Mos Def". The Irish Times. Archived from the original on June 16, 2016. Retrieved June 16, 2016.

- Caulfield, Keith (2009). "Black Eyed Peas 'E.N.D.' Up At No. 1 On Billboard 200". Billboard. Archived from the original on June 16, 2016. Retrieved June 5, 2016.

- Christgau, Robert (2009). "Consumer Guide". MSN Music. Archived from the original on January 15, 2011. Retrieved January 15, 2011.

- Christgau, Robert (2010). "The Dean's List: The Best Albums of 2009". The Barnes & Noble Review. Archived from the original on June 16, 2016. Retrieved June 5, 2016.

- Dantana (2009). "Updated: Mos Def Presents The Ecstatic Tour ft Jay Electronica". Okayplayer. Archived from the original on June 16, 2016. Retrieved June 6, 2016.

- Daulatzai, Sohail (2012). Black Star, Crescent Moon: The Muslim International and Black Freedom Beyond America. U of Minnesota Press. ISBN 0816675864.

- Diamond, Samuel (2013). "Yasiin Bey & Preservation – The REcstatic". Tiny Mix Tapes. Archived from the original on June 16, 2016. Retrieved June 13, 2016.

- Eisinger, Dale (2013). "The Ecstatic – The 50 Best Rap Album Covers of the Past Five Years". Complex. Archived from the original on June 16, 2016. Retrieved June 6, 2016.

- Faughnder, Ryan (2009). "Top 50 Albums of 2009 (Part One)". No Ripcord. Archived from the original on June 16, 2016. Retrieved July 11, 2015.

- Gundersen, Edna (2009). "Mos Def is Most Thoughtful as He Focuses on Myriad Projects". USA Today. Archived from the original on June 16, 2016. Retrieved June 4, 2016.

- Harling, Danielle (2009). "Drake, Mos Def And More Receive Grammy Nominations". HipHopDX. Archived from the original on June 16, 2016. Retrieved February 20, 2011.

- Henderson, Eric (2009). "Mos Def: The Ecstatic". Slant Magazine. Archived from the original on April 21, 2013. Retrieved April 21, 2013.

- Hoard, Christian (2009). "The Ecstatic : Mos Def : Review". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on June 5, 2016. Retrieved April 21, 2013.

- Huff, Quentin B. (2009). "Hip-Hop & the Contrast Principle". PopMatters. Archived from the original on June 16, 2016. Retrieved June 5, 2016.

- St. John, Colin (2009). "Review: Mos Def". Time Out. Archived from the original on June 16, 2016. Retrieved June 4, 2016.

- Jones, Steve (2009). "'Ecstatic' Elevates Def's Game". USA Today. Archived from the original on June 16, 2016. Retrieved June 13, 2016.

- Kellman, Andy (n.d.). "The Ecstatic – Mos Def". AllMusic. Archived from the original on April 21, 2013. Retrieved April 21, 2013.

- Kot, Greg (2009). "Turn It Up: Album Review: Mos Def's 'The Ecstatic'". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on April 21, 2013. Retrieved April 21, 2013.

- Lamb, Karas (2013). "Yasiin Bey & Preservation Present: 'The REcstatic'". Okayplayer. Retrieved June 13, 2016.

- MacInnes, Paul (2009). "Mos Def: The Ecstatic". The Guardian. Archived from the original on April 21, 2013. Retrieved April 21, 2013.

- Maness, Carter (2009). "Current TV Follows Mos Def Around Japan". The Boombox. Archived from the original on June 16, 2016. Retrieved June 6, 2016.

- Michaels, Sean (2009). "Mos Def to Release New Album ... on a T-shirt". The Guardian. Archived from the original on June 16, 2016. Retrieved June 3, 2016.

- Middles, Mick (2009). "Mos Def". The Quietus. Archived from the original on April 21, 2013. Retrieved April 21, 2013.

- Murray, Robin (2010). "Mos Def Unveils UK Tour". Clash. Archived from the original on June 16, 2016. Retrieved June 6, 2016.

- Owsinski, Bobby (2009). Music 3.0: A Survival Guide for Making Music in the Internet Age. Hal Leonard Corporation. ISBN 1423474015.

- Patrin, Nate (2009). "Mos Def: The Ecstatic". Pitchfork. Archived from the original on April 21, 2013. Retrieved April 21, 2013.

- Potton, Ed (2009). "Mos Def: The Ecstatic". The Times. Archived from the original on January 15, 2011. Retrieved January 15, 2011. (subscription required)

- Rabin, Nathan (2009). "Mos Def: The Ecstatic". The A.V. Club. Archived from the original on April 21, 2013. Retrieved April 21, 2013.

- Raible, Allan (2009). "Review: Mos Def's 'The Ecstatic'". ABC News. Archived from the original on June 16, 2016. Retrieved June 6, 2016.

- Richard (2009). "Mos Def – Casa Bey". DJBooth. Archived from the original on June 16, 2016. Retrieved June 5, 2016.

- Richman, Simmy (2009). "Album: Mos Def, The Ecstatic (Downtown)". The Independent. Archived from the original on April 21, 2013. Retrieved April 21, 2013.

- Samuel, Steven (2008). "Mos Def 'Ecstatic' About Upcoming CD". SOHH. Archived from the original on June 16, 2016. Retrieved June 5, 2016.

- Samuel, Steven (2009). "Mos Def Reveals New Album Details, Bringing Back Def Poetry". SOHH. Archived from the original on June 16, 2016. Retrieved June 4, 2016.

- Siehndel, Patrick; Abel, Fabian; Diaz-Aviles, Ernesto; Henze, Nicola; Krause, Daniel (2013). "Cross-Domain Analysis of the Blogosphere for Trend Prediction". In Özyer, Tansel; Rokne, Jon; Wagner, Gerhard; Reuser, Arno H. P. The Influence of Technology on Social Network Analysis and Mining. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 3709113466.

- Slavik, Nathan (2009). "Mos Def – The Ecstatic". DJBooth. Archived from the original on June 16, 2016. Retrieved June 4, 2016.

- Stewart, Allison (2009). "Music Review: Black Eyed Peas' 'The E.N.D.'; Mos Def's 'The Ecstatic'". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on June 16, 2016. Retrieved June 5, 2016.

- Thompson, Ben (2009). "CD: Pop Review: Mos Def, The Ecstatic". The Observer. Archived from the original on April 21, 2013. Retrieved April 21, 2013.

- Vozick-Levinson, Simon (2009). "The Ecstatic". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on June 16, 2016. Retrieved June 6, 2016.

- Young, Alex (2009). "Mos Def – The Ecstatic". Consequence of Sound. Archived from the original on June 16, 2016. Retrieved June 4, 2016.

Further reading

- Brie (2013). "Yasiin Bey x Preservation — The REcstatic Album Stream". Okayplayer.

- MissFrolab (2009). "Mos Def 'The Ecstatic' Liner Notes in Photos & Video". Frolab.

- MissFrolab (2009). "Mos Def: The Ecstatic Samples & Originals". Frolab.

External links

- The Ecstatic at Discogs (list of releases)

- The Ecstatic (Adobe Flash) at Myspace (streamed copy where licensed)