Tawau

| Tawau Tawao | ||

|---|---|---|

| Other transcription(s) | ||

| • Jawi | تاواو | |

| • Chinese | 斗湖 | |

|

Tawau town centre | ||

| ||

Location of Tawau in Sabah | ||

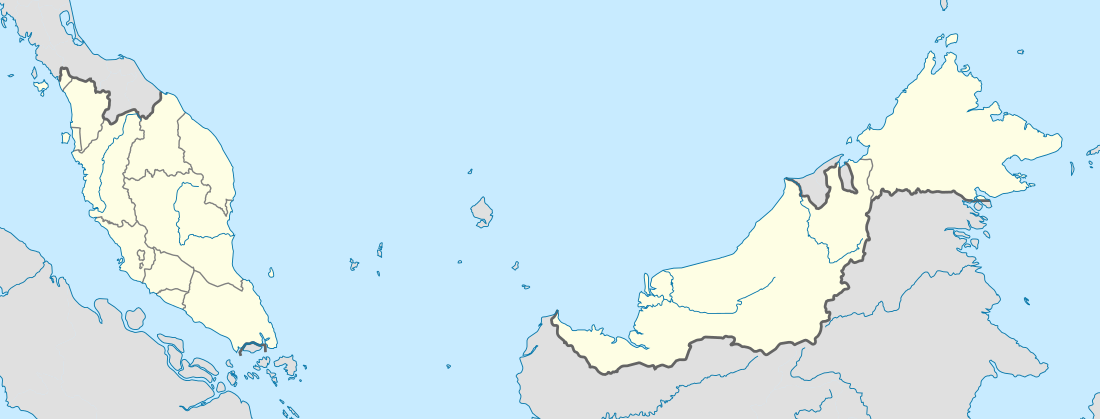

Tawau Tawau is located in Malaysia | ||

| Coordinates: 4°15′30″N 117°53′40″E / 4.25833°N 117.89444°ECoordinates: 4°15′30″N 117°53′40″E / 4.25833°N 117.89444°E | ||

| Country |

| |

| State |

| |

| Division | Tawau | |

| Bruneian Empire | 15th century–1658 | |

| Sultanate of Sulu | 1658–1882 | |

| Founded | 1893 | |

| Settled by BNBC | 1898 | |

| Municipality | 1 January 1982 | |

| Government | ||

| • Council President | Alijus Sipil | |

| Area | ||

| • Town | 55.9 km2 (21.6 sq mi) | |

| • Municipality | 6,125 km2 (2,365 sq mi) | |

| Elevation[1] | 8 m (26 ft) | |

| Population (2010) | ||

| • Town | 113,809 | |

| • Density | 2,000/km2 (5,300/sq mi) | |

| • Municipality | 397,673 | |

| Time zone | MST (UTC+8) | |

| • Summer (DST) | Not observed (UTC) | |

| Postal code | 91000 | |

| Area code(s) | 089 | |

| Vehicle registration | ST | |

| Website |

mpt | |

Tawau (Malaysian pronunciation: [ˈta wau], Jawi: تاواو, Chinese: 斗湖; pinyin: Dǒu Hú) formerly known as Tawao, is a town and administrative centre of Tawau Division, Sabah, Malaysia. It is the third-largest town in Sabah, after Kota Kinabalu and Sandakan. It is bordered by the Sulu Sea to the east, the Celebes Sea to the south at Cowie Bay[note 1] and shares a border with North Kalimantan. The town had an estimated population as of 2010 of 113,809,[2] while the whole municipality area had a population of 397,673.[2][note 2]

Before the founding of Tawau, the region around it was the subject of dispute between the British and Dutch spheres of influence. In 1893, the first British merchant vessel sailed into Tawau, marking the opening of the town's sea port. In 1898, the British set up a settlement in Tawau. The British North Borneo Chartered Company (BNBC) accelerated growth of the settlement's population by encouraging the immigration of Chinese. Consequent to the Japanese occupation of North Borneo, the Allied forces bombed the town, in mid-1944, razing it to the ground. After the Japanese surrender in 1945, 2,900 Japanese soldiers in Tawau became prisoners of war and were transferred to Jesselton. Tawau was rebuilt after the war and by the end of 1947 the economy was restored back into its pre-war status. Tawau was also the main point of conflict during the Indonesia–Malaysia confrontation from 1963 to 1966. During that time, it was garrisoned by the British Special Boat Section, and guarded by Australian Destroyers and combat aircraft. In December 1963, Tawau was bombed twice by Indonesia and shootings occurred across the Tawau-Sebatik Island international border. Indonesians were found trying to poison the town's water supply. In January 1965, a curfew was imposed to prevent Indonesian attackers from making contact with Indonesians living in the town. While in June 1965, another attempted invasion by the Indonesian forces was repelled by bombardment by an Australian Destroyer. Military conflict finally ended in December 1966.

Among the tourist attractions in Tawau are: The Tawau International Cultural Festival, Tawau Bell Tower, Japanese War Cemetery, Confrontation Memorial, Teck Guan Cocoa Museum, Tawau Hills National Park, Bukit Gemok, and Tawau Tanjung Markets. The main economic activities of the town are: timber, cocoa, oil palm plantations, and prawn farming.

History

Like most of part of Borneo, this area was once under the control of the Bruneian Empire[3] in the 15th century before been ceded to the Sultanate of Sulu between the 1600s[4] and 1700s[5] as a gift for helping the Bruneian forces during a civil war that happened in Brunei. The name Tawao was used on a nautical charts by 1857,[6] and there is evidence of a settlement by 1879. The East India Company had establish a trading post in Borneo, though there was no significant activity by the Dutch on the east coast.[7] In 1846, Netherlands formed a treaty with the Sultan of Bulungan, where the latter assured the Dutch control of the area.[7] When the Dutch began to operate in 1867, the Sultan married his son to the daughter of the Sultan of Tarakan. Around this time, the Dutch sphere of influence reached the Tawao. They controlled the area north of Tawao, overlapping an area controlled by the Sultan of Sulu.[7]

In 1878, Sultanate of Sulu sold the southern part of his land bounded by the Sibuco River to a Austro-Hungarian consul Baron von Overbeck, who later tried to sell the territory to the German Empire, Austria-Hungary and the Kingdom of Italy for use as a penal colony but failed, leaving Alfred Dent to manage and establishing the British North Borneo Chartered Company (BNBC).[8] The BNBC negotiated in the 1880s with the Dutch for a definition of a boundary between the area conferred by the Sultan of Sulu and the area that the Dutch claimed from Sultan of Bulungan to settle a dispute that arising from the unknown exact location of the real border between the territory that was held by the Sultanate of Sulu and the Sultanate of Bulungan.[7] On 20 January 1891, a final agreement was reached on a line along 4° 10' north latitude – on the central division of the Sebatik Island.[7][note 3] In the early 1890s, approximately 200 people lived in the Tawao settlement, mostly immigrants from Bulungan in Kalimantan, and some from Tawi-Tawi who had fled from Dutch and Spanish rule.[9][10][11] The settlement was renamed from Tawao to Tawau. Most of those who fled from the Dutch colonisation continued trading with the Dutch.[9] In 1893, a British vessel S.S. Normanhurst sailed into Tawau with a cargo to trade. In 1898, the British built a settlement which later grew rapidly when the BNBC sponsored the migration of Chinese to Tawau.[12][13]

On 16 December 1941, during World War II, the Japanese invasion of Borneo began. After the first landing in Miri, the Japanese moved along the coastline of Borneo from the oil fields of Kuching and towards Jesselton. Life in Tawau continued as usual until 24 January 1942 when the Japanese were sighted off Batu Tinagat. The district officer Cole Adams and his assistant were expecting an attack at the shipyard but were instead arrested by the Japanese.[note 4] The Allies began counterattacking the Japanese in mid-1944 with the bombing of Tawau. From 13 April 1945, six massive air strikes were made on town, concentrating on the port facilities. The last and largest of these attacks was on 1 May 1945 when 19 Liberator bombers bombed Tawau until it was completely razed to the ground.[14] After an unconditional surrender of the 37th Japanese Army under Lieutenant General Masao Baba in mid-September at Labuan, 1,100 Australian soldiers in Sandakan under the command of Lt. Col. JA England marched into the Japanese bases at Tawau. A total of 2,900 Japanese soldiers of the 370th battalion under Major Sugasaki Moriyuki were taken as prisoners of war and transferred to Jesselton.[15][16]

.jpg)

At the end of the war, the town had been largely destroyed by bombing and fire; the Bell tower was the only intact pre-war structure. Tawau quickly recovered. Though almost all the shops were destroyed, a report by The British North Borneo Annual Report in 1947 wrote that "the pre-war economy was largely made towards the end of 1947". In the first six months post-war, the British rebuilt 170 shops and commercial buildings. By 1 July 1947, subsidies for the purchase of rice and flour were introduced.[17]

Indonesian confrontation

Due to the its exposed location near the international border with Indonesia, Tawau become the main point of the conflict during the confrontation. In preparation for the impending conflict, Gurkhas were stationed in the town with other units including the "British No. 2 Special Boat Section" under Captain DW Mitchell.[18][19] Australian River-class destroyer escorts were stationed in Cowie Bay and a squadron of F-86 Sabre aircraft flew over Tawau daily from Labuan.

In October 1963, Indonesia moved their first battalion of the Korps Komando Operasi (KKO) from Surabaya to Sebatik and opened several training camps near the border in eastern Kalimantan (now North Kalimantan).[18][20] From 1 October to 16 December 1963, there were at least seven shootings along the border resulting in three Indonesians deaths. On 7 December 1963, an Indonesian Tupolev Tu-16 bomber flew over Tawau bay and bombed the town twice.[21]

By mid-December 1963, Indonesian had sent a commando unit consisting of 128 volunteers and 35 regular soldiers to Sebatik.[19] Their aim was to take Kalabakan, then invade Tawau and Sandakan.[19] On 29 December 1963, the Indonesian unit attacked the 3rd Royal Malay Regiment unit.[19] The Indonesians managed to throw several grenades into the totally unprepared Malay Regiment's sleeping quarters.[19] The attack resulted in eight Malay soldiers killed and nineteen wounded.[18] Malaysian armed police eventually drove the attackers north after a two-hour battle.[18]

In 1964, the situation remained tense in Tawau. A group of eight Indonesians were detained while trying to poison the water supply of the town. On 12 May 1964, there was a bombing attempt on the Kong Fah cinema.[22][23] At the end of January 1965, a night time curfew was imposed in Tawau to prevent attackers from contacting the approximate 16,000 Indonesians living there. By the end of February 1965, 96 of the 128 Indonesian volunteers had been killed or captured, around 20 successfully retreated to Indonesia, and 12 remained at large.[18] On 28 June 1965, an attempt by Indonesian troops to invade eastern Sebatik was repelled by a heavy bombardment by Australian destroyer HMAS Yarra.[24][25] In August 1965, an unknown assailant made an attempt to blow up a high-tension electricity pylon while in September 1965, a logging truck was destroyed by a land mine.[26] The confrontation largely ended 12 August 1966, and in December there was a complete ceasefire in Tawau.[27]

Government and International relations

Indonesia has a consulate in Tawau[28] and the town has twin town arrangements with Zhangping, China[29] and Pare-Pare, Indonesia.[30]

There are two members of parliament (MPs) representing the two parliamentary constituencies in the district: Tawau (P.190) and Kalabakan (P.191). The area is represented by six members of the Sabah State Legislative Assembly representing the districts of: Balung; Apas; Sri Tanjung; Merotai; Tanjung Batu; and Sebatik.[31]

The town is administered by the Tawau Municipal Council (Majlis Perbandaran Tawau). As of 2016, the President of Tawau Municipal Council is Alijus Sipil[32] who take over from Datuk Ismail Mayakob after serving for six years. The area under the jurisdiction of the Tawau District is the 2,510-hectare (25.1 km2) town area, 3,075-hectare (30.75 km2) surrounding populated area, 568,515 hectares (5,685.15 km2) of rural land and 38,406 hectares (384.06 km2) of adjacent sea area .[33]

Security

Today, Tawau is one of the six districts that involved in the eastern Sabah sea curfew that have been enforced since 19 July by the Malaysian government to repelling any attacks from militant groups in the Southern Philippines.[34]

Geography

Tawau is on the south-east coast of Sabah surround by the Sulu Sea in the east, Celebes Sea to the south and shares a border with East Kalimantan (now North Kalimantan).[33][35][36] The town is approximately 1,904 kilometres from the Malaysia's capital, Kuala Lumpur and is 540 kilometres south-east of Kota Kinabalu.[37] The main town area is divided into three sections named Sabindo, Fajar and Tawau Lama (Old Tawau).[38] Sabindo is a plaza, Fajar is a commercial area while Tawau Lama is the original part of Tawau. Almost 70% of the area surrounding Tawau is either high hills or mountainous.[39]

Climate

Tawau has a tropical rainforest climate under the Köppen climate classification. The climate is relatively hot and wet with average shade temperature about 26 °C (79 °F), with 29 °C (84 °F) at noon and falling to around 23 °C (73 °F) at night. The town sees precipitation throughout the year, with a tendency for November, December and January to be the wettest months, and February and March become the driest months. Tawau mean rainfall varies from 1800 mm to 2500 mm.[40][41]

| Climate data for Tawau | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 31.6 (88.9) |

31.4 (88.5) |

31.9 (89.4) |

32.3 (90.1) |

32.4 (90.3) |

31.8 (89.2) |

31.3 (88.3) |

31.5 (88.7) |

31.7 (89.1) |

31.9 (89.4) |

32.0 (89.6) |

31.9 (89.4) |

31.8 (89.2) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 26.1 (79) |

26.1 (79) |

26.6 (79.9) |

27.0 (80.6) |

27.2 (81) |

26.9 (80.4) |

26.4 (79.5) |

26.6 (79.9) |

26.5 (79.7) |

26.7 (80.1) |

26.7 (80.1) |

26.3 (79.3) |

26.6 (79.9) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 22.4 (72.3) |

22.3 (72.1) |

22.6 (72.7) |

23.1 (73.6) |

23.5 (74.3) |

23.3 (73.9) |

22.8 (73) |

22.9 (73.2) |

22.7 (72.9) |

23.0 (73.4) |

23.0 (73.4) |

22.6 (72.7) |

22.8 (73) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 138.3 (5.445) |

101.8 (4.008) |

100.5 (3.957) |

89.8 (3.535) |

126.3 (4.972) |

162.2 (6.386) |

207.3 (8.161) |

201.6 (7.937) |

178.7 (7.035) |

170.5 (6.713) |

150.3 (5.917) |

135.5 (5.335) |

1,762.8 (69.402) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 13 | 11 | 10 | 10 | 12 | 12 | 14 | 13 | 12 | 13 | 13 | 13 | 146 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 182.5 | 183.8 | 216.5 | 222.6 | 231.1 | 191.6 | 216.2 | 218.9 | 198.3 | 198.1 | 193.3 | 194.0 | 2,446.9 |

| Source: NOAA[42] | |||||||||||||

Demography

Ethnicity and religion

The Malaysian Census 2010 Report indicates that the whole Tawau municipality area has a total population of 397,673.[2][note 2] The town population today is a mixture of many different races and ethnicities. Non-Malaysian citizens form the majority of the town population with 164,729 people. Malaysian citizens in the area were reported divided into Bumiputras (Racially divided among Ethnic Malays (Cocos Malays, Buginese people and minorities of Javanese people), Bajau/Suluk, Kadazan-Dusun and Murut including (Tidong) sub-ethnic group) (134,456), Chinese (40,061), Indian (833) and others (mostly non-citizens) (6,153).[2]

The non-Malaysian citizens are mostly from Indonesia.[43] The Malaysian Chinese, like other places in Sabah, are mostly Hakkas who arrived after British rule ended. Their original settlements are around Apas Road which was originally an agricultural field.[44][45] The Bajau, Suluk and Malays are mostly Muslims. Kadazan-Dusuns and Muruts mainly practice Christianity though some of them are Muslim. Malaysian Chinese are mainly Buddhists though some are Taoist or Christians. There is a small number of Hindus, Sikhs, Animists, and secularists in the town.

The majority of non-citizens are Muslims, though some are Christian Indonesian who are mainly ethnic Florenese and Timorese that arrived since the 1950s.[46][47] A small number of Pakistanis also in the town, mainly working as shop or restaurant owners. Most non-citizens work and live at the plantation industry. Some of the migrant workers have been naturalised as a Malaysian citizens, however there are still many who live without proper documentation as illegal immigrants in the town with their own unlawful settlement.[43][46]

Al-Kauthar Mosque, the largest mosque in Sabah.[48]

Al-Kauthar Mosque, the largest mosque in Sabah.[48] The Holy Trinity Church, a Catholic church in Tawau.

The Holy Trinity Church, a Catholic church in Tawau.

Languages

The people of Tawau mainly speak Malay, with a distinct Sabahan creole.[49] The Malay language here are different from the Malay language in the west coast which resembles Brunei Malay.[50] In Tawau, the language had been influenced by the Indonesian language spoken by the Buginese, Florenese and Timorese.[43] As most Tawau Chinese are Hakka Chinese, Hakka Chinese is widely spoken. The east coast Bajau's language has similarities with the Sama language in the Philippines and has borrowed words from the Suluk language. The Bajau language on the east coast is different from the west coast Bajau, where the language has been influenced by Malayic languages from Brunei Malay.[51][52]

Economy

As of 1993, there were 40 timber-processing plants and a number of sawmills. Tawau's Port is a major export and import gateway for timber especially from North Kalimantan.[53][54] A barter trade has been formalised between East Kalimantan (now North Kalimantan) and Sabah with the creation of Tawau Barter Trade Association (BATS) in 1993. The association handles the cash-based trade of raw materials from Indonesia, but in recent years has focussed on timber industry.[53] Other than timber, since British rule ended exports have traditionally been spices, cocoa and tobacco.[55] Birds' nests are harvested at Baturong, Sengarung, Tepadung and Madai Caves by the Ida'an community.[56][57] Tawau is one of the top cocoa producers in Malaysia, and the world together with Ivory Coast, Ghana and Indonesia.[58] The town is the cocoa capital for both in Sabah and Malaysia.[59] Cocoa production is mostly concentrated in the interior, north of the town, while palm oil production is concentrated along the roads to Merotai, Brantian, Semporna and Kunak.[39] Both cocoa and palm oil are part of the large agriculture sector that has become the main income producer for the town.[60][61]

Like in Sandakan, people in Tawau have always relied on the sea for their sustenance. Every day, hundreds of deep sea trawlers and tuckboats can be seen at the Cowie Bay. In the sea also where the barter trade economy been used.[48] The Tawau marine zone are one of Sabah four marine zones, with the other been in Sandakan, Kudat and the west coast.[62] A great variety of high-grade fishes and all kinds of crustaceans were found in abundance in the sea and waterways around Tawau.[12] Prawn farming has become largest sea economic source for the district. The oldest and largest prawn farm were located on this area together with six frozen shrimp processing plants.[63][64]

Transportation

Most of the town's roads are state roads constructed and maintained by the state's Public Works Department. A program began in 2012 to upgrade the towns roads and increase the amount of public parking.[65] Most major internal roads are dual-carriageways. The only highway route from Tawau connects: Tawau – Semporna – Kunak – Lahad Datu – Sandakan (part of the Pan Borneo Highway)[66]

Regular bus services and taxis operate in the town. The town has long-distance, short-distance and local bus stations. The long-distance services connect Tawau to Lahad Datu, Sandakan, Telupid, Ranau, Simpang Sapi, Kundasang, Kota Kinabalu, Sipitang, Beaufort, Papar and Simpang Ranau.[67] The short-distance services connect to destinations including as Sandakan and Semporna.[68]

Tawau Airport (TA) (ICAO Code : WBKW) is the second largest airport in Sabah province, after Kota Kinabalu, and has flights linking the town mostly to domestic destinations. Destinations for the airport include Kota Kinabalu, Kuching and Kuala Lumpur. Flights by MASWings connect the airport to smaller towns or rural areas in East Malaysia, and internationally to Juwata International Airport in Tarakan, Indonesia. The airport opened in 2001 and as of 2012 handled almost one million passengers annually.[69] Prior to this the area was served by the Old Tawau Airport on North Street (Jalan Utara). The airport was opened in 1968 and was used for small aircraft such as the Fokker 50.[70] The runway was widened in the 1980s, allowing it to operate Boeing 737s. There was a fatal accident in 1995 when Malaysia Airlines Flight 2133, a Fokker 50, crashed due to pilot error on landing, leading to 34 fatalities. A Cessna 208 Caravan crashed on takeoff in 1995 and MAS Boeing 737-400 skidded off the runway in 2001, neither causing fatalities. The airport was closed when the new Tawau airport opened.[71]

There is a daily ferry service from northeastern Kalimantan to the town's sea port.[72] This route has been used for smuggling subsidised goods from the town to certain parts in Indonesia, especially southern Sebatik, by Indonesian smugglers as this area is highly dependent on Tawau.[73][74] Many Indonesians near the international border choose to seek a medical treatment in the town due to the lower cost and better facilities, compared to other Indonesian towns.[74]

Public Services

Tawau's court complex is on Dunlop Street.[75] It contains the High Court, Sessions Court, and the Magistrate Court.[76] Syariah Court is located at Abaca Street.[77] The district police headquarters is on Tanjung Batu Street,[78] and other police station are sited throughout the district including Wallace Bay, Bombalai, Bergosong, Kalabakan, Seri Indah and LTB Tawau.[79] Police substations (Pondok Polis) are found in Tass Bt. 17, Apas Parit, Merotai, Quin Hill, Balung Kokos, Titingan, Kinabutan and Burmas areas,[79] and the Tawau Prison is in the town centre.[80]

Tawau has one public hospital, four public health clinics, three child and mother health clinics, seven village clinics, one mobile clinic and two 1Malaysia clinics.[81][82] Tawau Hospital, on Tanjung Batu Street, is the town's main hospital and an important healthcare facility for patients from Semporna, Lahad Datu, Kunak, and Sandakan. Indonesian patients near the border area also frequently visit the hospital. Tawau Specialist Polyclinics (TSPC) is a walk-in healthcare clinic that sees patients from Tawau and surrounding areas as well as patients from neighbouring Philippines and Indonesia. TSPC has a range of medical specialists, a medical laboratory and radiology services.[74][83][84] The hospital has undergone a series of modernisations since 1990 with the construction of specialist clinics, Central Sterile Services Department (CSSD), new wards and operation theatres.[84] Tawau Specialist Hospital is the only private hospital in the town.[85] The Tawau Regional Library is one of three regional libraries in Sabah, the others are at Keningau and Sandakan. These libraries are operated by the Sabah State Library department.[86] Some schools, colleges, or universities have private libraries.[81]

There are many government or state schools in and around the town. Secondary schools include Sekolah Menengah Kebangsaan Kinabutan, Sekolah Menengah Kebangsaan Jalan Apas, Sekolah Menengah Kebangsaan Kabota, and Sekolah Menengah Kebangsaan Pasir Putih.[87][88] The town has two private schools, called the Sabah Chinese High School (Sekolah Tinggi Cina Sabah) and Vision Secondary School (Sekolah Menengah Visi). Tawau has two of the three A-Level education centres in the state of Sabah—the Institute of Science and Management (ISM) and Maktab Rendah Sains Mara Tawau.[89][90] A teacher-training college called Tawau Teacher Training Institute is found in the town. For tertiary education the town has the Tawau Community College[91] and GIATMARA Tawau,[92] and campuses of two universities, Universiti Teknologi MARA[93] and Open University Malaysia.

The Tawau Regional Library, one of the three regional libraries in Sabah.

The Tawau Regional Library, one of the three regional libraries in Sabah. The Tawau Court.

The Tawau Court. Universiti Teknologi MARA campus in Tawau.

Universiti Teknologi MARA campus in Tawau.

Culture and leisure

The Tawau International Cultural Festival is an annual event, first held in 2011, that has been promoted for its potential to attract tourists.[94] The Tawau Bell Tower in the town's park was built by the Japanese in 1921 shortly after World War I to mark the close allied relations between Japan and Great Britain.[12] Other historical attractions include the Japanese War Cemetery, Confrontation Memorial, the Public Service Memorial and the Twin Town Memorial. Tawau is one of the top cocoa production centres in Malaysia. The Teck Guan Cocoa Museum has become one of the important historical attractions for the town since it was founded in the 1970s by Datuk Seri Panglima Hong Teck Guan.[95] Varieties of cocoa products including chocolate jam and hot cocoa beverages are sold in the museum.[96]

Tawau has nearby conservation areas and areas set aside for leisure. The Tawau Hills National Park has picnic areas, a vast camping site, and cabins. It is 24 kilometres (15 miles) from Tawau and is accessible by road.[97] Bukit Gemok (also known as Fat Hill) is an approximately 428-metre (1,404 ft) hill about 11 km (7 mi) from the town. It is part of the 4.45-square-kilometre (1.72 sq mi) Bukit Gemok Forest Reserve, which was declared a forest reserve in 1984.[98][99] Tawau Harbour is used as a transit point to islands near the town including Sipadan, Mabul, Kapalai, Mataking, and Indonesian islands including southern Sebatik, Tarakan and Nunukan.

The main shopping area in Tawau is the Eastern Plaza located at Mile 1 on Kuhara Street. It was built in 2005, completed in 2008 and opened in May 2009. The complex has three levels of car parking with 476 covered and 49 surface parking bays.[100][101] Sabindo Plaza was opened in January 1999 and is known as the first shopping centre built in Tawau.[102] There is a market that runs alongside Dunlop Street.[103] The Tawau Tanjung Market was established in 1999. Since then, it has expanded to house 6,000 stalls and is known as the largest indoor market in Malaysia.[104][105]

The town has a sport complex with badminton, tennis, volleyball and basketball courts, and two stadiums for hockey and football.[106] In 2014, Youth and Sports Minister Khairy Jamaluddin announced formation of a National Sports Institute (ISN) in Tawau. It will be the third sports satellite centre in Sabah once completed in 2015.[107] A cross-border sporting event was held in 2014 between the town and Nunukan in Indonesia. It has been proposed to be repeated annually to strengthen ties between the towns.[108]

The Bell Tower (left) and the Public Service Memorial (right)

The Bell Tower (left) and the Public Service Memorial (right) A monument in the Tawau Japanese War Memorial

A monument in the Tawau Japanese War Memorial Sabindo Plaza, Tawau's first shopping centre.

Sabindo Plaza, Tawau's first shopping centre. Tawau Marker Hill.

Tawau Marker Hill.

Notable residents

- Political

- Chua Soon Bui: Malaysian politician[109]

- Entertainment

- Amber Chia: Malaysian model[110]

- Pete Teo: Malaysian singer-songwriter, musician, film producer, music producer and actor[111]

- Sports

- Julamri Muhammad: Malaysian football player[112][113]

- Muhd Rafiuddin Rodin: Malaysian football player[114][115]

- Shahrul Azhar Ture: Malaysian football player[112]

- Siswanto Haidi: Malaysian cricket player[116]

- Sumardi Hajalan: Malaysian football player[117][118]

Notes

- ↑ Cowie Bay in the early 19th century was known as Kalabakong Bay. It is also known as Sibuco Bay.

- 1 2 Above the official figures of the 2010 Census there are a large number of illegal immigrants from Indonesia and the Philippines.(Goodlet, page 248 and page 299)

- ↑ The final contractual commit this limit was indeed confirmed in 1912 by the joint boundary commission, and on 17 February 1913 by Dutch and British negotiators.

- ↑ Cole Adams spent 44 months in Japanese POW camps – first on the Berhala Island in Sandakan, later in Batu Lintang camp near Kuching – and died on the day of his liberation by the 9th Division of the Australian armed forces in September 1945.

References

- ↑ "Malaysia Elevation Map (Elevation of Tawau)". Flood Map : Water Level Elevation Map. Archived from the original on 22 August 2015. Retrieved 22 August 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 "Total population by ethnic group, Local Authority area and state, Malaysia, 2010" (PDF). Department of Statistics Malaysia. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 November 2013. Retrieved 14 September 2013.

- ↑ Mohd. Jamil Al-Sufri (Pehin Orang Kaya Amar Diraja Dato Seri Utama Haji Awang.); K. Agustinus; Mohd. Amin Hassan (2002). Survival of Brunei: a historical perspective. Brunei History Centre, Ministry of Culture, Youth and Sports.

- ↑ Frans Welman. Borneo Trilogy Volume 1: Sabah. Booksmango. pp. 160–. ISBN 978-616-245-078-5.

- ↑ Ben Cahoon. "Sabah". worldstatesmen.org. Retrieved 10 October 2014.

Sultan of Brunei cedes the lands east of Marudu Bay to the Sultanate of Sulu in 1704.

- ↑ British Museum, Sec. 13.2576; Facsimile at Goodlet, Page 6

- 1 2 3 4 5 R. Haller-Trost (1 January 1995). The Territorial Dispute Between Indonesia and Malaysia Over Pulau Sipadan and Pulau Ligitan in the Celebes Sea: A Study in International Law. IBRU. pp. 6–8–9. ISBN 978-1-897643-20-4. Retrieved 6 August 2013.

- ↑ Summaries of Judgments, Advisory Opinions and Orders of the International Court of Justice: 1997–2002. United Nations Publications. 2003. pp. 266–. ISBN 978-92-1-133541-5. Retrieved 6 August 2013.

- 1 2 "History of Tawau". e-tawau. 26 July 2008. Archived from the original on 17 April 2014. Retrieved 9 April 2014.

- ↑ William Shaw; Mohd. Kassim Haji Ali (1971). Paper Currency of Malaysia, Singapore, and Brunei (1849–1970). Muzium Negara.

- ↑ Paula Kay Byers (1 September 1995). Asian American genealogical sourcebook. Gale Research. ISBN 978-0-8103-9228-1.

- 1 2 3 Nicholas Chung (2005). Under the Borneo Sun: A Tawau Story. Natural History Publications (Borneo). ISBN 978-983-812-108-8.

- ↑ "History of Tawau Settlement" (in Malay). Tawau Municipal Council. Archived from the original on 6 April 2014. Retrieved 7 April 2014.

- ↑ Kit C. Carter; Robert Mueller (1975). The Army Air Forces in World War II: combat chronology, 1941–1945. Arno Press. Retrieved 7 August 2013.

- ↑ Gavin Long: Australia in the War: The Final Campaigns (Army), Australian War Museum, Canberra, Page 495, 564

- ↑ Bob Reece: Masa Jepun, Sarawak Literary Society, 1998

- ↑ Goodlet, Page 129

- 1 2 3 4 5 Will Fowler (2006). Britain's Secret War: The Indonesian Confrontation, 1962–66. Osprey Publishing. pp. 12–. ISBN 978-1-84603-048-2. Retrieved 6 August 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 J. P. Cross (1 January 1986). In Gurkha Company: The British Army Gurkhas, 1948 to the Present. Arms and Armour Press. ISBN 978-0-85368-865-5. Retrieved 6 August 2013.

- ↑ Malaysia. Dept. of Information; Malaysia. Kementerian Penerangan (1964). Indonesian involvement in eastern Malaysia. Dept. of Information. Retrieved 6 August 2013.

- ↑ Indonesian Aggression Against Malaysia. Ministry of External Affairs. 1964.

- ↑ SAIS Review. School of Advanced International Studies of the Johns Hopkins University. 1966. Retrieved 6 August 2013.

- ↑ "The Straits Times, 24 June 1964, Page 11 ($2,000 for helping to catch sabotage gang)". National Library Singapore. Retrieved 6 August 2013.

- ↑ Neil C. Smith (1999). Nothing Short of War: With the Australian Army in Borneo 1962–66. Mostly Unsung Military History Research and Publications. ISBN 978-1-876179-07-6. Retrieved 6 August 2013.

- ↑ Rongxing Guo (1 January 2006). Territorial Disputes and Resource Management: A Global Handbook. Nova Publishers. pp. 217–. ISBN 978-1-60021-445-5. Retrieved 6 August 2013.

- ↑ "The Straits Times, 30 September 1965, Page 22 (Indon land mine blows up truck, five hurt)". National Library Singapore. Retrieved 25 April 2014.

- ↑ Goodlet, Page 167–172

- ↑ "Consulate of the Republic of Indonesia in Tawau, Sabah, Malaysia". Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Republic of Indonesia. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- ↑ "Tawau to have sister-city partnership with Zhangping City". The Borneo Post. 3 June 2013. Archived from the original on 6 April 2014. Retrieved 6 August 2013.

- ↑ Bachtiar Adnan Kusuma (January 2001). Otonomi daerah: peluang investasi di kawasan Timur Indonesia (in Indonesian). Yapensi Multi Media. ISBN 978-979-95819-0-7.

- ↑ "Tawau Geography". Tawau Municipal Council. Archived from the original on 19 April 2014. Retrieved 20 April 2014.

- ↑ "Alijus in Tawau Council boss". Daily Express. 29 January 2016. Retrieved 30 January 2016.

- 1 2 "Tawau Position". Tawau Municipal Council. Archived from the original on 7 April 2014. Retrieved 8 April 2014.

- ↑ "Sea curfew in Sabah to be extended until Sept 2, say cops". The Star. Retrieved 4 November 2014.

- ↑ "Tawau Strategic Plan (2009–2015)" (PDF). Tawau Municipal Council. p. 5. Retrieved 8 April 2014.

- ↑ Wendy Hutton (November 2000). Adventure Guides: East Malaysia. Tuttle Publishing. pp. 77–. ISBN 978-962-593-180-7. Retrieved 8 August 2013.

- ↑ "Tawau to Kota Kinabalu Distance". Google Maps. Retrieved 9 April 2014.

- ↑ Lonely Planet; Daniel Robinson; Adam Karlin; Paul Stiles (1 May 2013). Lonely Planet Borneo. Lonely Planet. pp. 188–. ISBN 978-1-74321-651-4. Retrieved 8 August 2013.

- 1 2 "Rapid Survey of Development Opportunities & Constraints (Doc) for Tawau District". Town and Regional Planning Department, Sabah. 30 March 1999. Retrieved 15 April 2014.

- ↑ P. Thomas; F. K. C. Lo; A. J. Hepburn (1976). The land capability classification of Sabah. Land Resources Division, Ministry of Overseas Development.

- ↑ P. Thomas; F. K. C. Lo; A. J. Hepburn (1976). "The land capability classification of Sabah (Volume 1) – The Tawau Residency (Climate)" (PDF). Land Resources Division, Ministry of Overseas Development. p. 10/29. Retrieved 9 April 2014.

- ↑ "Tawau Climate Normals 1961–1990". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 24 March 2015.

- 1 2 3 Kamal Sadiq (2 December 2008). Paper Citizens: How Illegal Immigrants Acquire Citizenship in Developing Countries. Oxford University Press. pp. 48–. ISBN 978-0-19-970780-5.

- ↑ Danny Wong Tze-Ken (1999). "Chinese Migration to Sabah Before the Second World War". Archipel. p. 143. Retrieved 9 April 2014.

- ↑ Handbook of the State of British North Borneo: With a Supplement of Statistical and Other Useful Information. British North Borneo (Chartered) Company. 1934.

- 1 2 Alexander Horstmann; Reed L. Wadley (15 May 2006). Centering The Margin: Agency and Narrative in Southeast Asian Borderlands. Berghahn Books. pp. 143–. ISBN 978-0-85745-439-3.

- ↑ Geoffrey C. Gunn (18 December 2010). Historical Dictionary of East Timor. Scarecrow Press. pp. 71–. ISBN 978-0-8108-7518-0.

- 1 2 Tamara Thiessen (2012). Borneo: Sabah - Brunei - Sarawak. Bradt Travel Guides. pp. 226 & 230. ISBN 978-1-84162-390-0.

- ↑ "PEOPLE OF SABAH". Discovery Tours Sabah. Archived from the original on 28 March 2014. Retrieved 10 April 2014.

- ↑ Stephen Adolphe Wurm; Peter Mühlhäusler; Darrell T. Tyron (1996). Atlas of Languages of Intercultural Communication in the Pacific, Asia, and the Americas. Walter de Gruyter. pp. 1615–. ISBN 978-3-11-013417-9.

- ↑ Mark T. Miller (2007). A Grammar of West Coast Bajau. ProQuest. pp. 5–. ISBN 978-0-549-14521-9.

- ↑ Julie K. King; John Wayne King (1984). Languages of Sabah: Survey Report. Department of Linguistics, Research School of Pacific Studies, Australian National University. ISBN 978-0-85883-297-8.

- 1 2 Krystof Obidzinski (2006). Timber Smuggling in Indonesia: Critical Or Overstated Problem? : Forest Governance Lessons from Kalimantan. CIFOR. pp. 16 & 28. ISBN 978-979-24-4670-8.

- ↑ Yvonne Byron (1995). In Place of the Forest; Environmental and Socio-Economic Transformation in Borneo and the Eastern Malay Peninsula. United Nations University Press. pp. 219–. ISBN 978-92-808-0893-3.

- ↑ Herman Scholz (2 August 2009). "Tawau Heaven for divers". New Sabah Times. Retrieved 11 April 2014.

- ↑ Madeline Berma; Junaenah Sulehan; Faridah Shahadan (1–3 December 2010). ""White Gold": The Role of Edible Birds' Nest in the Livelihood Strategy of the Idahan Communities in Malaysia" (PDF). National University of Malaysia. Massey University. Retrieved 11 April 2014.

- ↑ Liz Price (27 September 2009). "Local tribesfolk nestling among the Madai Caves". The Brunei Times. Archived from the original on 11 April 2014. Retrieved 11 April 2014.

- ↑ K. Assis, A. Amran, Y. Remali and H. Affendy (2010). "A Comparison of Univariate Time Series Methods for Forecasting Cocoa Bean Prices" (PDF). Universiti Malaysia Sabah. World Cocoa Foundation. ISSN 1994-7933. Retrieved 11 April 2014.

- ↑ Fredrik Gustafsson (2002). "Cocoa Satellites (A study of the cocoa smallholder sector in Sabah, Malaysia)" (PDF). Lund University. pp. 20/22. Retrieved 11 April 2014.

- ↑ Mohd. Yaakub Hj. Johari; Bilson Kurus; Janiah Zaini (1997). BIMP-EAGA integration: issues and challenges. Institute for Development Studies (Sabah). ISBN 978-967-9910-47-6.

- ↑ Jailani Hassan (28 May 2013). "Agro sector remains main income earner for Tawau". The Borneo Insider. Archived from the original on 11 April 2014. Retrieved 11 April 2014.

- ↑ Hamid Awong (May 2008). Hamid Awong Fisheries Model (HAFM): A Case Study Stock Assesments [sic] of Demersal Fishes of Priacanthus Tayenus (Richardson 1846) in Darvel Bay, Sabah, Malaysia. Lulu.com. pp. 4–. ISBN 978-0-615-21321-7.

- ↑ Wim Giesen; FAO Regional Office for Asia and the Pacific (January 2006). Mangrove guidebook for Southeast Asia. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Regional Office for Asia and the Pacific. ISBN 978-974-7946-85-7.

- ↑ Hajjah Norasma Dacho, Rayner Datuk Stuel Galid and Alvin Wong Tsun Vui. "MARKETING AND EXPORT OF MARINE-BASED FOOD PRODUCTS" (PDF). Department of Fisheries, Sabah. pp. 15–16. Retrieved 13 April 2014.

- ↑ "Better roads, more parking lots for Tawau". The Borneo Post. 21 July 2012. Retrieved 16 April 2014.

- ↑ "INFRASTRUCTURE & SUPERSTRUCTURE (Road)". Borneo Trade (Source from Public Works Department, Sabah). Archived from the original on 19 June 2013. Retrieved 15 April 2014.

- ↑ "Long-distance bus terminal". e-tawau. 22 March 2014. Archived from the original on 17 April 2014. Retrieved 18 April 2014.

- ↑ "Sabindo Short-distance minibus station". e-tawau. 4 April 2014. Archived from the original on 17 April 2014. Retrieved 18 April 2014.

- ↑ "MAHB Annual Report 2012" (PDF). MAHB. Retrieved 6 September 2013.

- ↑ "Tawau Airport". Malaysia Airports. Archived from the original on 22 April 2014. Retrieved 23 April 2014.

- ↑ "Old Tawau Airport". e-tawau. Archived from the original on 22 April 2014. Retrieved 23 April 2014.

- ↑ Charles de Ledesma; Mark Lewis; Pauline Savage (2003). Malaysia, Singapore and Brunei. Rough Guides. pp. 504–. ISBN 978-1-84353-094-7.

- ↑ "Tawau Marine Police Foil Attempt To Smuggle Subsidised, Controlled Items". Bernama. 14 April 2014. Archived from the original on 17 April 2014. Retrieved 17 April 2014.

- 1 2 3 Godfrey Baldacchino (21 February 2013). The Political Economy of Divided Islands: Unified Geographies, Multiple Polities. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 70–. ISBN 978-1-137-02313-1.

- ↑ "Tawau Town Map". e-tawau. Retrieved 22 April 2014.

- ↑ "Court Addresses (THE HIGH COURT IN SABAH & SARAWAK)". The High Court in Sabah and Sarawak. Retrieved 21 April 2014.

- ↑ "Syariah Courts Address in Sabah". Department of Sabah State Syariah. Archived from the original on 21 April 2014. Retrieved 21 April 2014.

- ↑ "Tawau District Police Headquarters". Google Maps. Retrieved 22 April 2014.

- 1 2 "Direktori: Alamat dan telefon PDRM". Royal Malaysian Police. Archived from the original on 22 April 2014. Retrieved 22 April 2014.

- ↑ "Penjara Tawau (Alamat & Telefon Penjara)". Prison Department of Malaysia. Archived from the original on 30 March 2014. Retrieved 22 April 2014.

- 1 2 "16 Social Facilities". Town and Regional Planning Department, Sabah. Archived from the original on 30 March 2014. Retrieved 23 April 2014.

- ↑ "Clinics in Tawau". Sabah State Health Department. Retrieved 23 April 2014.

- ↑ "Peta Lokasi (Location Map)" (in Malay). Tawau Hospital. Archived from the original on 23 April 2014. Retrieved 23 April 2014.

- 1 2 "Pengenalan (Introduction)" (in Malay). Tawau Hospital. Archived from the original on 23 April 2014. Retrieved 23 April 2014.

- ↑ "Home". Tawau Specialist Hospital. Archived from the original on 15 September 2016. Retrieved 15 September 2016.

- ↑ "Tawau Regional Library". Sabah State Library Online. Archived from the original on 22 April 2014. Retrieved 22 April 2014.

- ↑ "SENARAI SEKOLAH MENENGAH DI NEGERI SABAH (List of Secondary Schools in Sabah) – See Tawau" (PDF). Educational Management Information System. Retrieved 22 April 2014.

- ↑ "SENARAI SEKOLAH MENENGAH DI SABAH SEPERTI PADA 31 JANUARI 2011 (List of Secondary Schools in Sabah as on 31 January 2011) – See Tawau" (PDF). Educational Management Information System. Retrieved 22 April 2014.

- ↑ "ISM History". Institute of Science and Management. 14 September 2009. Archived from the original on 22 April 2014. Retrieved 22 April 2014.

- ↑ "MRSM Tun Mustapha Tawau tawar A-Level pada 2014" (in Malay). The Borneo Post. 27 January 2013. Archived from the original on 22 April 2014. Retrieved 22 April 2014.

- ↑ "Laman Web Rasmi Kolej Komuniti Tawau (The Official Website of Tawau Community College". Kolej Komuniti Tawau (Tawau Community College) (in Malay). Archived from the original on 17 March 2015. Retrieved 17 March 2015.

- ↑ "Sepintas lalu – Giatmara Tawau (A brief introduction – Giatmara Tawau)" (in Malay). Giatmara Tawau. Archived from the original on 12 December 2013. Retrieved 17 March 2015.

- ↑ "UiTM Sabah Tawau Campus" (in Malay). UiTM Sabah. Archived from the original on 15 July 2013. Retrieved 17 March 2015.

- ↑ "Tawau cultural festival a potential tourism icon for Malaysia". Bernama. The Brunei Times. 28 February 2012. Archived from the original on 23 April 2014. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- ↑ "Teck Guan Cocoa Museum (Tawau, Sabah)". e-tawau. Archived from the original on 27 April 2014. Retrieved 28 April 2014.

- ↑ "Teck Guan Cocoa Museum". Sabah Tourism Board. Archived from the original on 27 April 2014. Retrieved 28 April 2014.

- ↑ "Tawau Hills Park". Sabah Tourism Board. Archived from the original on 25 June 2014. Retrieved 17 March 2015.

- ↑ "Bukit Gemok". Sabah Tourism Board. Archived from the original on 16 July 2014. Retrieved 17 March 2015.

- ↑ "Bukit Gemok". Sabah Tourist Association. Archived from the original on 18 March 2013. Retrieved 17 March 2015.

- ↑ "Eastern Plaza". Sabah Urban Development Corporation (SUDC). Archived from the original on 27 April 2014. Retrieved 27 April 2014.

- ↑ "Eastern Plaza Shopping Complex". e-tawau. Archived from the original on 27 April 2014. Retrieved 27 April 2014.

- ↑ "Sabindo Plaza (The First Shopping Centre in Tawau)". e-tawau. Archived from the original on 27 April 2014. Retrieved 27 April 2014.

- ↑ "Tanjung Market: Tawau's bestsecret for bargain hunters". The Brunei Times. Archived from the original on 27 April 2014. Retrieved 27 April 2014.

- ↑ "Tawau Tanjung Market". Sabah Tourism Board. Archived from the original on 27 April 2014. Retrieved 27 April 2014.

- ↑ "Tanjung Tawau market offers shoppers all kinds of items from 'amplang' to seaweed". Bernama. The Star. Retrieved 27 April 2014.

- ↑ "Tawau Sport Complex (Tawau Sport Complex Facilities Rental Rates)". Sabah Sports Board. Retrieved 28 April 2014.

- ↑ "Third Sports Satellite Centre For Sabah To Be Set Up in Tawau". Bernama. Eastern Sabah Security Command. 13 April 2014. Archived from the original on 27 April 2014. Retrieved 28 April 2014.

- ↑ "Hold Tawau-Nunukan Border-Sports annually: Tawfiq". Daily Express. 16 February 2014. Archived from the original on 27 April 2014. Retrieved 28 April 2014.

- ↑ "Members of Parliament (Chua Soon Bui)". Malaysian Parliament. Retrieved 15 March 2015.

- ↑ "Amber Chia Interview: A Model Of Determination". imoney.my. 9 February 2015. Retrieved 14 March 2015.

- ↑ Tashny Sukumaran; N. Rama Lohan (16 September 2013). "Marching to their own beat". The Star. Retrieved 15 March 2015.

- 1 2 "Sabah, Malaysia". New Sabah Times. p. 4. Retrieved 15 March 2015.

- ↑ "Julamri Bin Muhammad". Sabah FA. Archived from the original on 15 March 2015. Retrieved 15 March 2015.

- ↑ "Rafiuddin Rodin". European Football Database. Retrieved 15 March 2015.

- ↑ "Pulau Pinang masih perlu banyak pembaharuan" (in Malay). Sinar Harian. 21 November 2013. Retrieved 15 March 2015.

- ↑ "Siswanto Bin Moksun Haidi". CricketArchive. Retrieved 14 March 2015.

- ↑ Francis Xavier. "No comeback for Sumardi". New Sabah Times. Retrieved 15 March 2015.

- ↑ Shahrizal Zaini (27 September 2014). "Hijrah demi ilmu" (in Malay). Sinar Harian. Retrieved 14 March 2015.

Literature

- Ken Goodlet: Tawau – The Making of a Tropical Community, Opus Publications, 2010 ISBN 978-983-3987-38-2

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Tawau. |

-

Tawau travel guide from Wikivoyage

Tawau travel guide from Wikivoyage - Tawau Municipal Council

- Tawau Information