Tarring and feathering

Tarring and feathering is a form of public humiliation used to enforce unofficial justice or revenge. It was used in feudal Europe and its colonies in the early modern period, as well as the early American frontier, mostly as a type of mob vengeance (compare Lynch law).

In a typical tar-and-feathers attack, the mob's victim was stripped to the waist. Liquid tar was either poured or painted onto the person while he was immobilized. Then the victim either had feathers thrown on him or was rolled around on a pile of feathers so that they stuck to the tar. Often, the victim was then paraded around town on a cart or wooden rail. The aim was to inflict enough pain and humiliation on a person to make him either conform his behavior to the mob's demands or be driven from town.

The image of the tarred-and-feathered outlaw remains a metaphor for public humiliation. To "tar and feather" someone can mean to punish or severely criticize that person.[2][3]

Hypothetical comparison of tarring materials

Tarring and feathering was often presented in literature humorously as a punishment inflicting public humiliation and discomfort, but not serious injury. This would be hard to understand if the tar used were the material now most commonly referred to as "tar", which has a high melting point and would cause serious burns to the skin. However, the "tar" used then was pine tar, a completely different substance with a much lower melting point. Some varieties were liquid at room temperature.

Petroleum tar

Historically, petroleum tar was not used in the application of tarring and feathering for a variety of reasons. Modern tar, also called bitumen or asphalt, is produced from either petroleum or coal and typically used for tarring roads and roofs. The material must be sufficiently solid in normal weather conditions, including under the hot sun, so tar must have a high "softening point", the temperature at which the material becomes too soft to function properly.[4] Tar becomes increasingly liquid as temperature rises above this point. For example, one modern brand of roofing asphalt has a softening point of 100 °C (212 °F) but is applied at 190 °C (380 °F).[5] At the latter temperature, it has a relatively low viscosity. This kind of petroleum-based hot tar would burn any skin that it came into contact with. Paving materials, both coal and petroleum-based, are mixed at somewhat lower temperatures (105 °C (221 °F) for coal tar, 150–180 °C (302–356 °F) for bitumen),[6] but liquid would still be hot enough to cause severe injuries.

Pine tar

Pine tar is extracted from pine trees. It was used for waterproofing wooden ships and for weatherproofing rope. The character Ishmael in Moby Dick mentions "putting [one's] hand in the tar-pot" as one of the undignified things that sailors were expected to do. It was not a punishment but rather a standard task.[7]

Clearly, this would not have been possible with asphalt. Rope, unlike roads, must remain flexible, so the tar used had to be softer (closer to liquid) at lower temperatures. The melting point of pine tar is 55 to 60 °C (130 to 140 °F).[8] Pine tar’s boiling point is listed at 337 °C (639 °F).[8]

All of these materials are complex mixtures of hydrocarbons, including bitumen, coal tar, pine tar, and pitch. Their viscosity and temperature characteristics can vary greatly, depending on how they might be made and treated (though pitch is darker and thicker than tar by definition). Some pine tars had a consistency comparable to golden syrup at room temperature, in a manner similar to the different grades of molasses, whereas others were much blacker and more viscous. The latter had to be heated to a higher temperature to use, and so were called "hot tar".[9] Therefore, it is difficult to know the precise characteristics of the materials used in tarring and feathering, in any particular instance. Unless the tar was boiling, it was not necessarily an especially harmful procedure, and in some cases seems to have been more a matter of humiliation than torture.

History

The earliest mention of the punishment appears in orders that Richard I of England issued to his navy on starting for the Holy Land in 1189. "Concerning the lawes and ordinances appointed by King Richard for his navie the forme thereof was this ... item, a thiefe or felon that hath stolen, being lawfully convicted, shal have his head shorne, and boyling pitch poured upon his head, and feathers or downe strawed upon the same whereby he may be knowen, and so at the first landing-place they shall come to, there to be cast up" (transcript of original statute in Hakluyt's Voyages, ii. 21).[10][11]

A later instance of this penalty appears in Notes and Queries (series 4, vol. v), which quotes James Howell writing in Madrid in 1623 of the "boisterous Bishop of Halberstadt ... having taken a place where there were two monasteries of nuns and friars, he caused divers feather beds to be ripped, and all the feathers thrown into a great hall, whither the nuns and friars were thrust naked with their bodies oiled and pitched and to tumble among these feathers, which makes them here (Madrid) presage him an ill-death."[10](The Bishop was apparently Christian the Younger of Brunswick)

In 1696, a London bailiff attempted to serve process on a debtor who had taken refuge within the precincts of the Savoy. The bailiff was tarred and feathered and taken in a wheelbarrow to the Strand, where he was tied to a maypole that stood by what is now Somerset House as an improvised pillory.[10]

%2C_The_Bostonians_Paying_the_Excise-man%2C_or_Tarring_and_Feathering_(1774)_-_02.jpg)

Coming of the American Revolution

In 1766, Captain William Smith was tarred, feathered, and dumped into the harbor of Norfolk, Virginia by a mob that included the town's mayor. A vessel picked him out of the water just as his strength was giving out. He survived and was later quoted as saying that they "dawbed my body and face all over with tar and afterwards threw feathers on me." Smith was suspected of informing on smugglers to the British customs agents, as was the case with most other tar-and-feathers victims in the following decade.[12]

The practice appeared in Salem, Massachusetts in 1767, when mobs attacked low-level employees of the customs service with tar and feathers. In October 1769, a mob in Boston attacked a customs service sailor the same way, and a few similar attacks followed through 1774. The tarring and feathering of customs worker John Malcolm received particular attention in 1774. Such acts associated the punishment with the Patriot side of the American Revolution. An exception occurred in March 1775 when a British regiment inflicted the same treatment on Thomas Ditson, a Billerica, Massachusetts man who attempted to buy a musket from one of the regiment's soldiers. There is no known case of a person dying from being tarred and feathered in this period. During the Whiskey Rebellion, local farmers inflicted the punishment on federal tax agents.[13]

19th century

Joseph Smith, founder of the Latter Day Saint movement, was dragged from his home during the night of March 24, 1832 by a group of men who stripped and beat him before tarring and feathering him. His wife and infant child were knocked from their bed by the attackers and were forced from the home and threatened. (The infant died several days later from exposure.) Smith was left for dead, but limped back to the home of friends. They spent much of the night scraping the tar from his body, leaving his skin raw and bloody. The following day, Smith spoke at a church devotional meeting and was reported to have been covered with raw wounds and still weak from the attack.[14]

In 1851, a Know-Nothing mob in Ellsworth, Maine tarred and feathered Swiss-born Jesuit priest Father John Bapst in the midst of a local controversy over religious education in grammar schools. Bapst fled Ellsworth to settle in nearby Bangor, Maine, where there was a large Irish-Catholic community, and a local high school there is named for him.[15]

Tarring and feathering was not restricted to men. The November 27, 1906 Ada, Oklahoma Evening News reports that a vigilance committee consisting of four young married women from East Sandy, Pennsylvania corrected the alleged evil conduct of their neighbor Mrs. Hattie Lowry in whitecap style. One of the women was a sister-in-law of the victim. The women appeared at Mrs. Lowry's home in open day and announced that she had not heeded the spokeswoman and leader. Two women held Mrs. Lowry to the floor while the other two smeared her face with stove polish until it was completely covered. They then poured thick molasses upon her head and emptied the contents of a feather pillow over the molasses. The women then marched the victim to a railroad camp, tied by the wrists, where two hundred workmen stopped work to watch the spectacle. After parading Mrs. Lowry through the camp, the women tied her to a large box where she remained until a man released her.

20th century

A group of black-robed Knights of Liberty (a faction of the KKK) tarred and feathered seventeen members of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) in Oklahoma in 1917, during an incident known as the Tulsa Outrage.[16]

In the 1920s, vigilantes were opposed to IWW organizers at California's harbor of San Pedro. They kidnapped at least one organizer, subjected him to tarring and feathering, and left him in a remote location.

The Wednesday, May 28, 1930 edition of the Miami Daily News-Record contains on its front page the arrests of five brothers from Louisiana accused of tarring and feathering Dr. S. L. Newsome, who was a prominent dentist. This was in retaliation for the dentist having an affair with one of the brother's wives.

There were several examples of tarring and feathering of African-Americans in the lead-up to World War I in Vicksburg, Mississippi.[17] According to William Harris, this was a relatively rare form of mob punishment to Republican African-Americans in the post-bellum U.S. South, as its goal was typically pain and humiliation rather than death.[17]

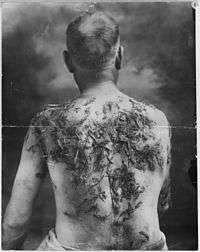

During World War I, anti-German sentiment was widespread and many German-Americans were attacked. For example, in August 1918 a German-American farmer, John Meints of Luverne, Minnesota (pictured above), was captured by a group of men, taken to the nearby South Dakota border and tarred and feathered – for allegedly not supporting war bonds. Meints sued his assailants and lost, but on appeal to a federal court he won, and in 1922 settled out of court for $6,000.[18] In March 1922, a German-born Catholic priest in Slaton, Texas, Joseph M. Keller, who had been harassed by local residents during World War I due to his ethnicity, was accused of breaking the seal of confession and tarred and feathered. Thereafter Keller served a Catholic parish in Milwaukee, Wisconsin.[19]

Similar tactics were also used by the Provisional Irish Republican Army (IRA) during the early years of The Troubles. Many of the victims were women accused of sexual relationships with policemen or British soldiers.[20] In August 2007, loyalist groups in Northern Ireland were linked to the tarring and feathering of an individual accused of drug-dealing.[21]

See also

References

- ↑ http://www.startribune.com/nov-16-1919-tarred-and-feathered/70155507/

- ↑ "Tar and Feather. The American Heritage Dictionary of Idioms by Christine Ammer. Houghton Mifflin Company". Dictionary.reference.com. 1997-05-26. Retrieved 2012-03-07.

- ↑ "Tars. The Free Online Dictionary". Thefreedictionary.com. Retrieved 2012-03-07.

- ↑ The substance is a mixture of a large number of different complex hydrocarbons and lacks a single melting point.

- ↑ "Owens-Corning Trumbull Technical Report: Effects on asphalt softening points of various time and temperature operating conditions" (PDF). Retrieved 2012-03-07.

- ↑ Nicholls, J Cliff (2002-11-01). Asphalt Surfacings. CRC Press. pp. 315, 377. ISBN 9780203477632. Retrieved 21 April 2014.

- ↑ Melville, Herman (1892). Moby Dick: Or, The White Whale. Page. p. 10. Retrieved 21 April 2014.

- 1 2 "Pine Tar MSDS". Canadian Centre for Occupational Health and Safety.

- ↑ Outland, Robert (2004). Tapping the Pines: The Naval Stores Industry in the American South. Louisiana State University Press. p. 22. Retrieved 8 May 2014.

- 1 2 3 Chisholm 1911.

- ↑ Tha Avalon Project documents Accessed on 23rd June 2015

- ↑ "Letters of Governor Francis Fauquier" (1912). The William and Mary Quarterly. 21. pp. 166–67.

- ↑ Benjamin H. Irvin, "Tar, feathers, and the enemies of American liberties, 1768-1776." New England Quarterly (2003): 197-238. in JSTOR

- ↑ See Life of Joseph Smith from 1831 to 1834#Life in Kirtland, Ohio

- ↑

Campbell, Thomas (1913). "John Bapst". In Herbermann, Charles. Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. Retrieved December 17, 2008.

Campbell, Thomas (1913). "John Bapst". In Herbermann, Charles. Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. Retrieved December 17, 2008. - ↑ Chapman, Lee Roy (September 2011). "The Nightmare of Dreamland This Land". Retrieved September 1, 2011.

- 1 2 Harris, William J. "Etiquette, Lynching, and Racial Boundaries in Southern History: A Mississippi Example". The American Historical Review. Vol. 100, No. 2 (Apr., 1995), pp. 387–410

- ↑ "Nov. 16, 1919: Tarred and feathered". StarTribune.com. Retrieved 2012-03-07.

- ↑ Bills, E. R. (October 29, 2013). Texas Obscurities: Stories of the Peculiar, Exceptional and Nefarious. "Father Keller": Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 9781625847652.

- ↑ Theroux, Paul (February 13, 2011). "This was England". The Observer. London.

- ↑ "Belfast man tarred and feathered". London: BBC News Online. August 28, 2007. Retrieved August 28, 2007.

Attribution

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Tarring and Feathering". Encyclopædia Britannica. 26 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Tarring and Feathering". Encyclopædia Britannica. 26 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Tarring and feathering. |

- Text of law of Richard I

- "Has anyone actually ever been tarred and feathered?" at Straight Dope

- Richard L. Bushman, Joseph Smith: Rough Stone Rolling., Alfred Knopf, 2005, ISBN 1-4000-4270-4