tar (computing)

| Filename extension |

.tar |

|---|---|

| Internet media type |

application/x-tar |

| Uniform Type Identifier (UTI) | public.tar-archive |

| Magic number |

u s t a r \0 0 0 at byte offset 257 |

| Latest release |

various (various) |

| Type of format | File archiver |

| Standard | POSIX since POSIX.1, presently in the definition of pax |

| Open format? | Yes |

In computing, tar is a computer software utility for collecting many files into one archive file, often referred to as a tarball, for distribution or backup purposes. The name is derived from (t)ape (ar)chive, as it was originally developed to write data to sequential I/O devices with no file system of their own. The archive data sets created by tar contain various file system parameters, such as name, time stamps, ownership, file access permissions, and directory organization. The command line utility was first introduced in the seventh edition of unix (v7) in January 1979, replacing the tp program.[1] The file structure to store this information was later standardized in POSIX.1-1988[2] and later POSIX.1-2001.[3] and became a format supported by most modern file archiving systems.

Rationale

Many historic tape drives read and write variable-length data blocks, leaving significant wasted space on the tape between blocks (for the tape to physically start and stop moving). Some tape drives (and raw disks) only support fixed-length data blocks. Also, when writing to any medium such as a filesystem or network, it takes less time to write one large block than many small blocks. Therefore, the tar command writes data in blocks of many 512 byte records. The user can specify a blocking factor, which is the number of records per block; the default is 20, producing 10 kilobyte blocks (which was large when UNIX was created, but now seems rather small).[4]

File format

A tar archive consists of a series of file objects, hence the popular term tarball, referencing how a tarball collects objects of all kinds that stick to its surface. Each file object includes any file data, and is preceded by a 512-byte header record. The file data is written unaltered except that its length is rounded up to a multiple of 512 bytes. The original tar implementation did not care about the contents of the padding bytes, and left the buffer data unaltered, but most modern tar implementations fill the extra space with zeros.[5] The end of an archive is marked by at least two consecutive zero-filled records. (The origin of tar's record size appears to be the 512-byte disk sectors used in the Version 7 Unix file system.) The final block of an archive is padded out to full length with zeros.

Header

The file header record contains metadata about a file. To ensure portability across different architectures with different byte orderings, the information in the header record is encoded in ASCII. Thus if all the files in an archive are ASCII text files, and have ASCII names, then the archive is essentially an ASCII text file (containing many NUL characters).

The fields defined by the original Unix tar format are listed in the table below. The link indicator/file type table includes some modern extensions. When a field is unused it is filled with NUL bytes. The header uses 257 bytes, then is padded with NUL bytes to make it fill a 512 byte record. There is no "magic number" in the header, for file identification.

Pre-POSIX.1-1988 (i.e. v7) tar header:

| Field Offset | Field Size | Field |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 100 | File name |

| 100 | 8 | File mode |

| 108 | 8 | Owner's numeric user ID |

| 116 | 8 | Group's numeric user ID |

| 124 | 12 | File size in bytes (octal base) |

| 136 | 12 | Last modification time in numeric Unix time format (octal) |

| 148 | 8 | Checksum for header record |

| 156 | 1 | Link indicator (file type) |

| 157 | 100 | Name of linked file |

The pre-POSIX.1-1988 Link indicator field can have the following values:

| Value | Meaning |

|---|---|

| '0' or (ASCII NUL) | Normal file |

| '1' | Hard link |

| '2' | Symbolic link |

Some pre-POSIX.1-1988 tar implementations indicated a directory by having a trailing slash (/) in the name.

Numeric values are encoded in octal numbers using ASCII digits, with leading zeroes. For historical reasons, a final NUL or space character should also be used. Thus although there are 12 bytes reserved for storing the file size, only 11 octal digits can be stored. This gives a maximum file size of 8 gigabytes on archived files. To overcome this limitation, star in 2001 introduced a base-256 coding that is indicated by setting the high-order bit of the leftmost byte of a numeric field. GNU-tar and BSD-tar followed this idea. Additionally, versions of tar from before the first POSIX standard from 1988 pad the values with spaces instead of zeroes.

The checksum is calculated by taking the sum of the unsigned byte values of the header record with the eight checksum bytes taken to be ascii spaces (decimal value 32). It is stored as a six digit octal number with leading zeroes followed by a NUL and then a space. Various implementations do not adhere to this format. For better compatibility, ignore leading and trailing whitespace, and take the first six digits. In addition, some historic tar implementations treated bytes as signed. Implementations typically calculate the checksum both ways, and treat it as good if either the signed or unsigned sum matches the included checksum.

Unix filesystems support multiple links (names) for the same file. If several such files appear in a tar archive, only the first one is archived as a normal file; the rest are archived as hard links, with the "name of linked file" field set to the first one's name. On extraction, such hard links should be recreated in the file system.

UStar format

Most modern tar programs read and write archives in the UStar (Uniform Standard Tape ARchive) format, introduced by the POSIX IEEE P1003.1 standard from 1988. It introduced additional header fields. Older tar programs will ignore the extra information (possibly extracting partially named files), while newer programs will test for the presence of the "ustar" string to determine if the new format is in use. The UStar format allows for longer file names and stores additional information about each file. The maximum filename size is 256, but it is split among a preceding path "filename prefix" and the filename itself, so can be much less.[6]

| Field Offset | Field Size | Field |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 156 | (several fields, same as in old format) |

| 156 | 1 | Type flag |

| 157 | 100 | (same field as in old format) |

| 257 | 6 | UStar indicator "ustar" then NUL |

| 263 | 2 | UStar version "00" |

| 265 | 32 | Owner user name |

| 297 | 32 | Owner group name |

| 329 | 8 | Device major number |

| 337 | 8 | Device minor number |

| 345 | 155 | Filename prefix |

The Type flag field can have the following values:

| Value | Meaning |

|---|---|

| '0' or (ASCII NUL) | Normal file |

| '1' | Hard link |

| '2' | Symbolic link |

| '3' | Character special |

| '4' | Block special |

| '5' | Directory |

| '6' | FIFO |

| '7' | Contiguous file |

| 'g' | global extended header with meta data (POSIX.1-2001) |

| 'x' | extended header with meta data for the next file in the archive (POSIX.1-2001) |

| 'A'–'Z' | Vendor specific extensions (POSIX.1-1988) |

| All other values | reserved for future standardization |

POSIX.1-1988 vendor specific extensions using link flag values 'A'..'Z' partially have a different meaning with different vendors and thus are seen outdated and replaced by the POSIX.1-2001 extensions that also include a vendor tag.

Type '7' (Contiguous file) is formally marked as reserved in the POSIX standard, but was meant to indicate files which ought to be contiguously allocated on disk. Few operating systems support creating such files explicitly, and hence most TAR programs do not support them, and will treat type 7 files as if they were type 0 (regular). An exception is older versions of GNU tar, when running on the Masscomp RTU (Real Time Unix) operating system, which supported an O_CTG flag to the open() function to request a contiguous file; however, that support was removed from GNU tar version 1.24 onwards.

POSIX.1-2001/pax

In 1997, Sun proposed a method for adding extensions to the tar format. This method was later accepted for the POSIX.1-2001 standard. This format is known as extended tar-format or pax-format. The new tar format allows users to add any type of vendor-tagged vendor-specific enhancements. The following enhancement tags are defined by the POSIX standard:

- all three time stamps of a file in arbitrary resolution (most implementations use nanosecond granularity)

- path names of unlimited length and character set coding

- symlink target names of unlimited length and character set coding

- user and group names of unlimited length and character set coding

- files with unlimited size (the historic tar format is 8 GB)

- userid and groupid without size limitation (this historic tar format was is limited to a max. id of 2097151)

- a character set definition for path names and user/group names

In 2001, the Star program became the first tar to support the new format. In 2004, GNU tar supported the new format, though it does not write them as its default output from the tar program yet.

It is relatively new and so not as supported. Its extensions are stored themselves as files within the tar, for somewhat backward compatibility.[7]

Uses

Tarpipe

A tarpipe is the method of creating an archive on the stdout file of the tar utility and piping it to another tar process on its standard input, working in another directory, where it is unpacked. This process copies an entire source directory tree including all special files, for example:

tar cf - srcdir | (cd destdir && tar xv)

Software distribution

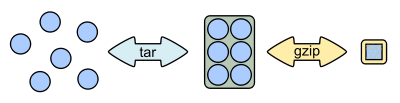

The tar format continues to be used extensively for open-source software distribution. Linux versions use features prominently in various software distributions, with most software source code made available in gzip compressed tar archives (.tar.gz file suffix).

Limitations

The original tar format was created in the early days of UNIX, and despite current widespread use, many of its design features are considered dated.[8]

Many older tar implementations do not record nor restore extended attributes (xattrs) or ACLs. In 2001, Star introduced support for ACLs and extended attributes, through its own extensions. Bsdtar has its own extensions to support ACL's.[9] More recent versions of GNU tar support extended attributes,[10] using its own tar extensions.

Other formats have been created to address the shortcomings of tar. These formats include DAR (Disk Archiver) and rdiff-backup (see Duplicity branch of the Savannah software site). However, these formats are not part of any official standard.

Operating system support

Unix-like operating systems usually include tools to support tar files, as well as utilities commonly used to compress them, such as gzip and bzip2. There are multiple third party tools available for Microsoft Windows to read and write these formats.

Tarbomb

A related problem is the use of absolute paths or parent directory references when creating tar files. Files extracted from such archives will often be created in unusual locations outside the working directory and, like a tarbomb, have the potential to overwrite existing files. However, modern versions of GNU tar do not create or extract absolute paths and parent-directory references by default, unless it is explicitly allowed with the flag -P or the option --absolute-names. The bsdtar program, which is also available on many operating systems and is the default tar utility on Mac OS X v10.6, also does not follow parent-directory references or symbolic links.[11]

A command line user can avoid these problems by first examining a tar file with the following command:

tar tf archive.tar

These commands do not extract any files, but display the names of all files in the archive. If any are problematic, the user can create a new empty directory and extract the archive into it—or avoid the tar file entirely. Most graphical tools can display the contents of the archive before extracting them. Vim can open tar archives and display their contents. GNU Emacs is also able to open a tar archive and display its contents in a dired buffer.

Random access

Another weakness of the tar format compared to other archive formats (like DAR or Zip) is that there is no centralized location for the information about the contents of the file (a "table of contents" of sorts). So to list the names of the files that are in the archive, one must read through the entire archive and look for places where files start. Also, to extract one small file from the archive, instead of being able to look up the offset in a table and go directly to that location, like other archive formats, with tar, one has to read through the entire archive, looking for the place where the desired file starts. For large tar archives, this causes a big performance penalty, making tar archives unsuitable for situations that often require random access of individual files.

The possible reason for not using a centralized location of information is that tar was originally meant for tapes, which are bad at random access anyway: if the Table Of Contents (TOC) were at the start of the archive, creating it would mean to first calculate all the positions of all files, which needs doubled work, a big cache, or rewinding the tape after writing everything to write the TOC. On the other hand, if the TOC were at the end-of-file (as is the case with ZIP files, for example), reading the TOC would require that the tape be wound to the end, also taking up time and degrading the tape by excessive wear and tear. Compression further complicates matters; as calculating compressed positions for a TOC at the start would need compression of everything before writing the TOC, a TOC with uncompressed positions is not really useful (since one has to decompress everything anyway to get the right positions) and decompressing a TOC at the end of the file might require decompressing the whole file anyway, too.

But today there are a number of add-on utilities which implement tar file indexing, thus enabling random access, both for raw tar files and for tar files compressed with gzip (which is amenable to indexing). Such an index can be kept in a separate file, appended or prepended to the archive file.

Duplicates

Another issue with tar format is that it allows several (possibly different) files in archive to have identical path and filename. When extracting such archive, usually the latter version of a file overwrites the former.

This can create a non-explicit (unobvious) tarbomb, which technically does not contain files with absolute paths or referring parent directories, but still causes overwriting files outside current directory (for example, archive may contain two files with the same path and filename, first of which is a symlink to some location outside current directory, and second of which is a regular file; then extracting such archive on some tar implementations may cause writing to the location pointed to by the symlink).

Key implementations

Historically, many systems have implemented tar, and many general file archivers have at least partial support for tar (often using one of the implementations below). Most tar implementations can also read and create cpio and pax (the latter actually is a tar-format with POSIX-2001-extensions).

Key implementations in order of origin:

- Solaris tar, based on the original UNIX V7 tar and comes as the default on the Solaris operating system

- star (unique standard tape archiver), written in 1982 by Jörg Schilling, is published under the CDDL-license. A test of star, reported in 1999, achieved a throughput of more than 14 MB/s[12] giving it the label of "fastest known implementation of a tar archiver"[13]

- GNU tar is the default on most Linux distributions. It is based on the public domain implementation pdtar which started in 1987. Recent versions can use various formats, including ustar, pax, GNU and v7 formats.

- FreeBSD tar (also BSD tar) has become the default tar on most Berkeley Software Distribution-based operating systems including Mac OS X. The core functionality is available as libarchive for inclusion in other applications. This implementation automatically detects the format of the file and can extract from tar, pax, cpio, zip, jar, ar, xar, rpm and ISO 9660 cdrom images.

Additionally, most pax implementations can read and create many types of tar files.

Suffixes for compressed files

tar archive files usually have the file suffix .tar, e.g., somefile.tar. The slang term tarball is sometimes used to refer to a tar file that has been compressed and renamed.

A tar archive file contains uncompressed byte streams of the files which it contains. To achieve archive compression, a variety of compression programs are available, such as gzip, bzip2, xz, lzip, lzma, or compress, which compress the entire tar archive. Typically, the compressed form of the archive receives a filename by appending the format-specific compressor suffix to the archive file name. For example, a tar archive archive.tar, is named archive.tar.gz, when it is compressed by gzip.

Popular tar programs like the BSD and GNU versions of tar support the command line options Z (compress), z (gzip), and j (bzip2) to automatically compress or decompress the archive file upon creation or unpacking. GNU tar from version 1.20 onwards also supports the option --lzma' (LZMA). 1.21 also supports lzop by specifying --lzop, 1.22 adds support for xz with --xz or -J, and 1.23 adds support for lzip with --lzip.

MS-DOS's 8.3 filename limitations resulted in additional conventions for naming compressed tar archives. (This practice has declined with FAT offering long filenames.)

| Long | Short |

|---|---|

| .tar.bz2 | .tb2, .tbz, .tbz2 |

| .tar.gz | .tgz |

| .tar.lz | |

| .tar.lzma | .tlz |

| .tar.xz | .txz |

| .tar.Z | .tZ |

See also

- Comparison of file archivers

- Comparison of archive formats

- List of archive formats

- List of Unix programs

References

- ↑ https://www.freebsd.org/cgi/man.cgi?query=tar&sektion=5

- ↑ IEEE Std 1003.1-1988, IEEE Standard for Information Technology - Portable Operating System Interface (POSIX)

- ↑ IEEE Std 1003.1-2001, IEEE Standard for Information Technology - Portable Operating System Interface (POSIX)

- ↑ "Blocking'" ftp.gnu.org. Retrieved 28 November 2013.

- ↑ http://www.e7z.org/open-tar.htm

- ↑ https://www.gnu.org/software/tar/manual/html_section/tar_68.html

- ↑ https://www.gnu.org/software/tar/manual/html_section/tar_68.html

- ↑ Proposed format to replace tar, by the Duplicity utility's developers.

- ↑ http://unix.stackexchange.com/a/104035/8337

- ↑ http://www.lesbonscomptes.com/pages/extattrs.html

- ↑ Man page for "bsdtar", as provided by Apple.

- ↑ Unix Backup and Recovery. O'Reilly Series. W. Curtis Preston (contributor). O'Reilly Media, Inc. 1999. p. 142. ISBN 9781565926424. Retrieved 2014-01-16.

The star utility [...] has been tested at speeds exceeding 14 MB/s.

- ↑ https://www.rpmfind.net/linux/RPM/opensuse/updates/13.1/ppc64/star-1.5final-61.11.1.ppc64.html

External links

- "tar(5): format of tape archive files". FreeBSD Manual Pages. FreeBSD Project. Includes documentation on how different implementations store various types of information and specialize headers.

- "libarchive - BSD-licensed library with tar file support".

- "The standard tar command". The Open Group.

- "The tar Command". The Linux Information Project (LINFO).

- "Detailed information on Tar and USTAR file headers".

- "tar(1) man page". OpenBSD Manual Pages. OpenBSD Project.

- "Tar — GNU Project". Free Software Foundation (FSF).

- Tar7 - A portable open source tar program written in Seed7

- Java Tar API with UStar format support

- Java Tar API With Gnutar Support

- File extension .TAR

- More about tarbomb

- sltar Suckless Tar (sltar) - MIT/X Consortium Licensed tar library

- libtar - A tar library by Mark D. Roth, University of Illinois