Takoma Park, Maryland

| Takoma Park, Maryland | ||

|---|---|---|

| City | ||

| City of Takoma Park | ||

|

The intersection of Laurel and Carroll Avenues | ||

| ||

Location in the U.S. state of Maryland | ||

| Coordinates: 38°58′48″N 77°0′8″W / 38.98000°N 77.00222°WCoordinates: 38°58′48″N 77°0′8″W / 38.98000°N 77.00222°W | ||

| Country |

| |

| State |

| |

| County |

| |

| Founded | 1883 | |

| Incorporated | 1890 | |

| Government | ||

| • Type | Municipal council-manager | |

| • Mayor | Kate Stewart | |

| • City manager | Suzanne Ludlow | |

| Area[1] | ||

| • Total | 5.41 km2 (2.09 sq mi) | |

| • Land | 5.39 km2 (2.08 sq mi) | |

| • Water | 0.03 km2 (0.01 sq mi) | |

| Elevation | 121 m (400 ft) | |

| Population (2010)[2] | ||

| • Total | 16,715 | |

| • Estimate (2013[3]) | 17,721 | |

| • Density | 3,102.8/km2 (8,036.1/sq mi) | |

| Time zone | EST (UTC-5) | |

| • Summer (DST) | EDT (UTC-4) | |

| Area code(s) | 301 | |

| FIPS code | 24-76650 | |

| GNIS feature ID | 0598146 | |

| Website | http://www.takomaparkmd.gov/ | |

Takoma Park is a city in Montgomery County, Maryland. It is a suburb of Washington, D.C., and part of the Washington metropolitan area. Founded in 1883 and incorporated in 1890, Takoma Park, informally called "Azalea City," is a Tree City USA and a nuclear-free zone. A planned commuter suburb, it is situated along the Metropolitan Branch of the historic Baltimore and Ohio Railroad, just northeast of Washington, D.C., and it borders the neighborhood of Takoma, Washington, D.C. It is governed by an elected mayor and six elected councilmembers, who form the city council, and an appointed city manager, under a council-manager style of government. The city's population was 16,715 at the 2010 national census.[4]

Since 2013, residents of Takoma Park can vote in municipal elections when they turn sixteen.[5] It was the first city in the United States to extend voting rights to 16- and 17-year-olds in city elections.[5] Since then, the City of Hyattsville has done the same.[6]

History

19th century

Takoma Park was founded by Benjamin Franklin Gilbert in 1883.[7] It was one of the first planned Victorian commuter suburbs, centered on the B&O railroad station in Takoma, D.C., and bore aspects of a spa and trolley park.

Takoma was originally the name of Mount Rainier, from Lushootseed [təqʷúbəʔ] (earlier *təqʷúməʔ), 'snow-covered mountain'.[8] In response to a wish of Gilbert, the name Takoma was chosen in 1883 by DC resident Ida Summy, who believed it to mean 'high up' or 'near heaven'.[9]

Gilbert's first purchase of land was in the spring of 1884 when he bought 100 acres (0.40 km2) of land from G.C. Grammar, which was known as Robert's Choice.[7][10] This plot of land was located on both sides of the railroad station, roughly bounded by today's Sixth Street on the west, Aspen Street on the south, Willow Avenue on the east, and Takoma Avenue on the north.[7] At the time, much of the land was covered by thick forest, some which cleared away in order to lay out and grade streets and housing lots.[11] At its founding, most lots measured 50 by 200 feet (15 by 60 m)[11] and were sold for $327 to $653 per acre.[12] By August 1885, there was about 100 people living in Takoma Park, including temporary summer residents and year-round permanent residents.[11] Gilbert himself lived in a wooden house on a stone foundation, with 20 rooms and a 65-foot (20 m) tower.[11]

Gilbert purchased another plot of land in 1886.[13] The land was roughly bounded by Carroll Avenue to the Big Spring (now Takoma Junction) and what is now Woodland Avenue.[13] Gilbert named this land New Takoma.[13] Gilbert later purchased the Jones farm and the Naughton farm, which together he named North Takoma.[13] He also purchased land from Francis P. Blair, Richard L. T. Beale, and the Riggs family.[10]

Gilbert hired contractor Fred E. Dudley to build many of the homes in Takoma Park. One of the homes built by Dudley was the home of Cady Lee,[7] which still stands today at Piney Branch Road and Eastern Avenue. Dudley's son Wentworth was the first child born in Takoma Park.[7]

By 1888, there were 75 houses built in the community,[12] and the number increased to 235 homes by 1889.[13] In 1889, Gilbert purchased several acres of land along Sligo Creek from a physician in Boston named Dr. R.C. Flower, in order to build a sanitarium on the land.[14] By this point, Takoma Park stretched 1,500 acres (5 km2).[10]

The deed of each of the original houses prohibited alcohol from being made or sold on the property,[10][12][13] a prohibition that continued in the city until 1983.[15] Takoma Park incorporated as a town on April 3, 1890.[16] The first town election was held on May 5, 1890, and Gilbert was elected mayor and J. Vance Lewis, George H. Bailey, Daniel Smith, and Frederick J. Lung were elected to the town council.[17]

Many of the streets were originally known as avenues.[13] When the Commissioners of the District of Columbia mandated a District-wide street-naming system, those on the District side were renamed streets but retained their names otherwise.[13] Other streets in Takoma D.C. were renamed entirely. Susquehanna Avenue became Whittier Street. Tahoe Street was renamed Aspen Street. Umatilla Street became Aspen Street. Vermilion Street became Cedar Street. Wabash Street was renamed Dahlia Street. Aspin became Elder Street. Magnolia Street became Eastern Avenue.[18]

Early 20th century

In 1904, the Seventh-day Adventist Church purchased five acres of land in Takoma Park along Carroll Avenue, Laurel Avenue, and Willow Avenue.[19] The land was located on both sides of the Maryland-District of Columbia border.[19] The land was intended for a church, office building, printer, and residences for prominent members of the church.[19] In 1903, the Seventh-day Adventist Church decided to move their headquarters to the Washington area after its headquarters' publishing house in Battle Creek, Michigan, had burned to the ground.[20] The church decided that moving to a more urban setting would be a more appropriate place from which to increase the church's presence in the southern states.[21] The church purchased fifty acres of land along Sligo Creek in Takoma Park to build the new headquarters.[22] The land was away from downtown Washington and had clean water available from a natural spring located at present-day Spring Park.[23] For many decades Takoma Park served as the world headquarters of the Seventh-day Adventist Church,[24] until it moved to northern Silver Spring in 1989.[23]

Late 20th century

In 1964, an inside-the-Capital-Beltway extension of Interstate 70S, also known as the North Central Freeway, was proposed via a route known as "Option #11 Railroad Sligo East," up to 1⁄4 mile parallel to the B&O railroad upon a swath of land displacing 471 houses, that would have cut the city in two. In the mid-to-late 1960s, the future Mayor and civil rights activist Sam Abbott led a campaign to halt freeway construction and replace it with a Metrorail line to the site of the former train station, and worked with other neighborhood groups to halt plans for a wider system of freeways going into and out of DC.

This controversy also raised the profile of Takoma Park at a time in the late 1960s and 1970s when it was becoming noted regionally and nationally for political activism outside the Nation's capital, with newspaper commentators describing it as "The People's Republic of Takoma Park" or "The Berkeley of the East".[25]

Much of the old town Takoma Park was incorporated into the Takoma Park Historic District; listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1976.

Before 1995, the eastern boundary of the city of Takoma Park was in Prince George's County, Maryland, causing the community to be divided across two counties and the Maryland/D.C. line (where the original downtown area is located). For several years, Takoma Park lobbied the State of Maryland for legislation allowing county boundaries to be adjusted. The State finally agreed to this change, with the stipulation that cross-county municipalities would no longer be allowed; the new municipal boundary would forever remain within the county of its choosing. In August 1995, after passage of the law, the city held a public referendum asking registered voters living in three Prince George's County neighborhoods north of New Hampshire Avenue whether they wanted to be annexed to the city of Takoma Park. There was a majority of votes, 211 out of 304, in favor of annexation to the city.[26]

In November 1995, the state-sponsored referendum was held asking whether the portions of the city in Prince George's County should be annexed to Montgomery County, or vice versa. The majority of votes in the referendum were in favor of unification of the entire city in Montgomery County.[27] Following subsequent approval by both counties' councils and the Maryland General Assembly, the county line was moved to include the entire city into Montgomery County (including territory in Prince George's County newly annexed by the city) on July 1, 1997.[28] This process became known as Unification (see the Takoma Voice's 10-year retrospective on Unification). .

The city has experienced substantial gentrification in the 1990s and early 2000s (decade), with many group houses containing accessory apartments being converted back into single-family homes. This process was encouraged by an M-NCPPC "phase back", effectively eliminating scattered-site multifamily housing and implementing single-use zoning citywide, which prompted calls by some residents[29] for the city to have its own planning authority. The majority of the city's population remain tenants, many of whom live in a cluster of high-rise and mid-rise apartment buildings surrounding Sligo Creek, which cuts a deep valley through the community.

Geography

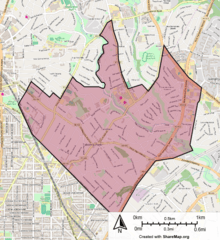

Takoma Park sits on the edge of the Mid-Atlantic fall line and is thus quite hilly, with many narrow, gridded streets. According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 2.09 square miles (5.41 km2), of which, 2.08 square miles (5.39 km2) is land and 0.01 square miles (0.03 km2) is water.[1] Sligo Creek and Long Branch (both tributaries of the Northwest Branch of the Anacostia River) flow through the area. Sligo Creek Park and the 9-mile (14 km) Sligo Creek Trail bisect the area. The main street, Carroll Avenue, and the main state highway, Route 410/East West Highway, narrow to two lanes within city limits. Takoma Park has an extensive hardwood tree canopy which is protected by local ordinance.

Takoma Park is bounded by downtown Silver Spring, Maryland, a major urban center to the northwest, by Montgomery College campus; East Silver Spring, a community of houses, apartments and small shops, along Flower Avenue and Piney Branch Road, to the north; Langley Park, Maryland, a community of apartments and shopping centers, along University Boulevard to the northeast; Chillum, Maryland, in Prince George's County to the southeast, bounded by New Hampshire Avenue, a state highway; and Takoma, Washington, D.C. to the southwest, separated by Eastern Avenue, which follows the District of Columbia line.

The corner of Eastern and Carroll Avenues roughly marks the center of the old commercial district. Other town centers include: "Takoma Junction", the corner of Carroll Avenue and Route 410 in the geographic center of town, home to the city's large food co-op; Takoma-Langley Crossroads in downtown Langley Park, and the Flower shopping district, both of which are home to many immigrant-owned establishments. Takoma Park's municipal center is located at the corner of Maple Avenue and Route 410. Washington Adventist University marks the corner of Carroll and Flower Avenues.

Neighborhoods by Ward

- Ward 1

- Hodges Heights

- Old Takoma a.k.a. the Philadelphia-Eastern Neighborhood

- North Takoma

- Ward 2

- B.F. Gilbert Subdivision (an extension of Old Town)

- Glaizewood Manor

- Long Branch-Sligo

- South of Sligo

- Ward 3

- SS Carroll Neighborhood, named after the addition made by Samuel S. Carroll[30][31] Also known "The Generals" streets: Grant Ave, Lee Ave, Sherman Ave, Sheridan Ave.

- Pinecrest

- Takoma Junction

- Westmoreland Area

- Ward 4

- Maple Ave apartment district

- Ritchie Ave

- Ward 5

- Between the Creeks (part of the greater Long Branch / East Silver Spring area centered along Flower Ave)

- Ward 6

- Hillwood Manor

- New Hampshire Gardens

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1890 | 164 | — | |

| 1900 | 756 | 361.0% | |

| 1910 | 1,242 | 64.3% | |

| 1920 | 3,168 | 155.1% | |

| 1930 | 6,415 | 102.5% | |

| 1940 | 8,938 | 39.3% | |

| 1950 | 13,341 | 49.3% | |

| 1960 | 16,799 | 25.9% | |

| 1970 | 18,507 | 10.2% | |

| 1980 | 16,231 | −12.3% | |

| 1990 | 16,700 | 2.9% | |

| 2000 | 17,299 | 3.6% | |

| 2010 | 16,715 | −3.4% | |

| Est. 2015 | 17,713 | [32] | 6.0% |

2014 census estimate

The United States Census Bureau estimated Takoma Park's population to be 17,670 in 2014.[34]

2013 census estimate

Fifty-two percent of working residents age 16 or older use public transportation, use a carpool, walk to work, or work at home.[35] The average commuting time is 38 minutes.[35]

Of Takoma Park's residents, 17 percent are of Subsaharan African ancestry, 11 percent have German ancestry, 8 percent are of Irish ancestry, 8 percent have English ancestry, and 4 percent are of West Indian ancestry.[36]

2010 census

As of the census[2] of 2010, there were 16,715 people, 6,569 households, and 3,904 families residing in the city. The population density was 8,036.1 inhabitants per square mile (3,102.8/km2). There were 7,162 housing units at an average density of 3,443.3 per square mile (1,329.5/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 49.0% White, 35.0% African American, 0.3% Native American, 4.4% Asian, 0.1% Pacific Islander, 6.5% from other races, and 4.8% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 14.5% of the population.

There were 6,569 households of which 33.6% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 40.9% were married couples living together, 14.2% had a female householder with no husband present, 4.3% had a male householder with no wife present, and 40.6% were non-families. 31.0% of all households were made up of individuals and 8.7% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.49 and the average family size was 3.12.

The median age in the city was 38 years. 22.4% of residents were under the age of 18; 8.1% were between the ages of 18 and 24; 30.8% were from 25 to 44; 28.7% were from 45 to 64; and 10% were 65 years of age or older. The gender makeup of the city was 46.6% male and 53.4% female.

2000 census

As of the census[37] of 2000, there were 17,299 people, 6,893 households, and 3,949 families residing in the city. The population density was 8,152.4 inhabitants per square mile (3,147.7/km2). There were 7,187 housing units at an average density of 3,387.0 per square mile (1,307.7/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 48.79% White, 33.97% African American, 0.44% Native American, 4.36% Asian, 0.03% Pacific Islander, 7.44% from other races, and 4.97% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 14.42% of the population.

There were 6,893 households out of which 30.8% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 38.5% were married couples living together, 14.2% had a female householder with no husband present, and 42.7% were non-families. Approximately 4.5% of all couples were unmarried same sex couples.[38] 32.2% of all households were made up of individuals and 7.9% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.44 and the average family size was 3.13.

In the city the population was spread out with 23.6% under the age of 18, 8.8% from 18 to 24, 35.9% from 25 to 44, 23.0% from 45 to 64, and 8.8% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 36 years. For every 100 females there were 89.1 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 85.9 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $48,490, and the median income for a family was $63,434. Males had a median income of $40,668 versus $35,073 for females. The per capita income for the city was $26,437. About 8.4% of families and 10.3% of the population were below the poverty line, including 10.5% of those under age 18 and 20.5% of those age 65 or over.

Economy

According to the City's 2014 Comprehensive Annual Financial Report,[39] the top employers in the city are the following.

| # | Employer | # of Employees |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Washington Adventist Hospital | 1,600 |

| 2 | Montgomery College | 523 |

| 3 | Montgomery County Public Schools | 215 |

| 4 | City of Takoma Park | 212 |

| 5 | Washington Adventist University | 163 |

| 6 | Sligo Creek Center (medical facility) | 133 |

| 7 | Republic (restaurant) | 68 |

| 8 | International House of Pancakes | 54 |

| 9 | Don Bosco Cristo Rey High School | 50 |

| 10 | Takoma Park/Silver Spring Co-op (food co-op) | 44 |

Culture

Takoma Park is known for a variety of cultural events, most notable of which is the Takoma Park Folk Festival, which attracts an audience from across the Mid-Atlantic region.

The Takoma Park Folk Festival is a music festival held annually in the city. It has been in existence since 1978, founded by Sam Abbott, former Mayor of the city and civil-rights activist.[40] In addition to hosting concerts on several stages by musicians from around the world, the festival also celebrates cultural diversity of the region, with a wide variety of ethnic food and crafts.

The festival features numerous varieties of music from local and national artists, including blues, klezmer, bluegrass, Celtic, and hip-hop, and traditional music and dance from around the world. Other performers specialize in traditional and progressive folk music. In addition to music and dance, the festival features traditional storytellers from around the world.[41]

Takoma Park is notable for being the home of Takoma Records, a nationally-known blues label started by blues guitarist John Fahey, who (together with other local music institutions) popularized the city as a haven for folk musicians. Mary Chapin Carpenter, Al Petteway (composer of Sligo Creek) and many other prominent local and national artists have made their home in and around Takoma Park. Root Boy Slim and Goldie Hawn are from Takoma Park.

Other annual festivals include the mildly countercultural Takoma Park Street Festival, the Takoma Jazz Fest, the Takoma Park Independent Film Festival, and the Takoma Park Fourth of July Parade, which is attended by residents and neighboring politicians from across the metropolitan region.[42] The parade typically includes ethnic musical troupes representing a wide variety of global cultures, neighborhood performance troupes, and groups supporting causes, such as LGBTQ and fair trade, reflecting Takoma Park's historic reputation for activism.

Immediately adjacent to the downtown, Takoma, D.C. is home to the A.Salon Building, a large art studio warehouse and former printing plant, which is home to the backstage office and rehearsal center for the Washington Opera. Two (currently vacant) freestanding theaters, the Takoma Theater and the Flower Theater, anchor either end of town. Takoma Park is also home to the Liz Lerman Dance Exchange and the Institute of Musical Traditions, a performance society founded by the House of Musical Traditions. Kinetic Artistry, a notable theatre supplier for the Washington area, is also located in Takoma Park. A Historic Takoma Museum is under construction by the local historic society. The Takoma Theatre Conservancy is an organization attempting to renovate the 500-seat Takoma Theatre for multiuse purposes.[43] The Federal Communications Commission (FCC) awarded a Construction Permit to Historic Takoma Inc (HTI) for Takoma Radio. The hyper-local neighborhood station will be identified on the air as WOWD-LP, 94.3FM, and has plans to debut in mid-2016.[44]

Takoma Park has been home to a variety of local characters who have contributed to the city's sense of identity and culture, including "Catman" and Motor Cat,[45] Roscoe the Rooster,[46] The Banjo Man,[47] and "Fox Man",[48] a local animal rights activist and founder of the city's Tool Library. Takoma Park also has a year round farmer's market and two other farmers markets which sell local produce and free range meats.

Underground filmmaker Nick Zedd grew up in Takoma Park and made his first movies there.

Institutions

The Sam Abbott Citizens Center, Takoma Park's former city auditorium, has been refurbished as a community theater and gallery.[49] The municipal center, which includes the Takoma Park City Hall, Citizens Center and the Takoma Park Maryland Library, was expanded into a community center from 2003-2007. A gymnasium was requested by the city's youth sports leagues after lobbying from Steve Francis, the NBA basketball player, who grew up in Takoma Park; but funding was not identified.[50] A small fenced in basketball court has since been built adjacent to the community center.

In 2010, the Seventh-Day Adventist Church received authorization to relocate the regional Washington Adventist Hospital from the center of town to an outlying area of nearby Silver Spring, Maryland, alongside its international headquarters and the Adventist Book and Health Food Store, which had also been located within city limits. This had followed an effort by county officials to close or relocate the city's fire station, located on the side of a steep hill. Due to resulting controversy, the City Council lobbied to retain the old Hospital facility as a "health campus." The hospital had been in operation for over a century, having been founded as the Washington Sanitarium overlooking Sligo Creek, shortly after the church's relocation from Battle Creek, Michigan. Officials also successfully lobbied to retain a university located on the same campus, which has been renamed Washington Adventist University.

In the 1970s, the city experienced controversy over plans to expand or relocate Montgomery College, which has a campus located in the historic district of North Takoma, an area of large old homes adjacent to downtown Silver Spring. This debate was subsequently resolved when the County agreed to preserve the existing campus, and expand in the direction of downtown Silver Spring by building a bridge across the B&O railroad tracks. It was renamed the "Takoma Park-Silver Spring Campus," focused on health, nursing and the arts. The expanded campus included a major new arts center located in South Silver Spring, near the boundary between the three jurisdictions. The Washington Adventist Hospital will be moving to an alternate location within the next five years.

The Takoma Park-Silver Spring Food Co-op is one of the Washington area's largest food co-ops. The Takoma Park Presbyterian Church has been a bulwark of civic activism throughout its history. The TPPC helped to found CASA de Maryland.

In the late 2000s (decade), regional and national debate occurred over the decision to close Walter Reed Army Medical Center in Takoma, D.C., and relocate its operations to the Bethesda Naval Medical Center. Takoma Park Soccer Club is the sponsor of many youth soccer teams in the Takoma Park area; such as the TAPK United, coached by professional Brazilian coach Manilton Santos. A successful team, they have earned the affectionate nickname Tapioca United.

Law and government

Takoma Park's electorate and its elected officials are known for their liberal and left-of-liberal values, which have led to the enactment of several municipal laws. For instance, Takoma Park allows non-U.S.-citizen residents to vote in its own municipal elections, and has lowered their voting age to 16.[5] The city was also forbidden, by statute, from doing business with any entity having commercial ties with the government of Burma (Myanmar),[51] though after a United States Supreme Court decision struck down a similar Massachusetts provision, enforcement of the provision was suspended in the year 2000. As of 2007, the Free Burma Committee is inactive.[52] In 2008, the city unanimously approved a resolution to oppose foie gras.[53]

Takoma Park is noted for being a "Nuclear Free Zone" along with cities including Berkeley, California; Cleveland Heights, Ohio; Madison, Wisconsin; and Homer, Alaska. It has an active Nuclear Free Zone Committee that advocates for nuclear disarmament and is entrusted with making purchasing recommendations to the city. Employees are forbidden from purchasing from companies involved in the production of nuclear weapons or their components. Contractors working for the city must also sign a notarized document that they are not "engaged in the development, research, production, maintenance, storage, transportation and/or disposal of nuclear weapons or their components."[54] Waivers have been given in the past, including a waiver to purchase a library system from Userful corporation that includes computers made by Hewlett-Packard, a company that has also worked on nuclear weapons programs for the United States government.[55]

Because Takoma Park is a certified Tree City, its residents must obtain a permit from the City arborist to cut down any tree on their property measuring more than 8 inches in diameter. This has contributed to the preservation of second-growth hardwood forest which covers much of the city, as is visible in satellite photos.

Takoma Park is chartered with its own police force, public works department, housing department, library, and recreation department. It has also historically maintained its own Volunteer Fire Department and Municipal Library. Until 2007, the city operated a Tool Library as well, and continues to operate its own compost recycling program and silo for corn-burning stoves. As one of the most urbanized areas outside Washington, D.C., Takoma Park is densely developed with narrow houses on deep lots, often featuring mid-block developments and a mix of apartments and homes which are no longer permitted under regional suburban zoning laws, under which many apartments were de-zoned in 1989. Development and reconstruction of the fire station and other public facilities have been highly controversial, with some advocating that facilities be closed and moved to outlying, automobile-friendly areas.

Mayor

Takoma Park is governed by a city council composed of a mayor and council members for each of six wards. The current mayor of Takoma Park is Kate Stewart.[56]

Former mayors are:

- Benjamin Franklin Gilbert (1890–1892)

- Enoch Maris (1892–1894)

- Samuel S. Shedd (1894–1902)

- John B. Kinnear (1902–1906)

- Wilmer G. Platt (1906–1912)

- Stephens W. Williams (1912–1917)

- Wilmer G. Platt (1917–1920)

- James L. Wilmeth (1920–1923)

- Henry D. Thizzle (1923–1926)

- Ben G. Davis (1926–1932)

- Frederick L. Lewton (1932–1936)

- John R. Adams (1936–1940)

- Oliver W. Youngblood (1940–1948)

- John C. Post (1948–1950)

- Ross H. Beville (1950–1954)

- George M. Miller (1954–1972)

- John D. Roth (1972–1980)

- Sammie A. Abbott (1980–1985)

- Stephen J. Del Giudice (1985–1990)

- Edward F. Sharp (1990–1997)

- Kathy Porter (1997–2007)

- Bruce Williams (2007-2015)

- Kate Stewart (Since 2015)

Voting

In the November 5, 1991, election the voters approved a referendum (1,199 for and 1,107 against) to change the Takoma Park City Charter "to permit residents of Takoma Park who are not U.S. citizens to vote in Takoma Park elections."[57]

In the 2005 election, an advisory referendum on the institution of Instant-Runoff Voting (IRV) for municipal elections passed with 84% approval.[17] In 2006, the City Council amended the City Charter to incorporate IRV. With this, Takoma Park joins a small but growing number of municipalities across the nation who have chosen IRV, such as San Francisco, California and Ferndale, Michigan.

In the 2009 election, Takoma Park used the Scantegrity voting system. This marked the first time an open source voting system was used in a public sector election in the United States, as well as the first time a system with end-to-end verifiability was used.

In 2013, Takoma Park became the first city in the U.S. to allow sixteen- and seventeen-year-olds to vote.[5]

Convicted felons on parole and probation were also given the right to vote in Takoma Park elections in 2013.[5]

Transportation

Being part of Montgomery County, Takoma Park is served by both the Ride On bus system, and by the Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority, which provides bus and rail service to the Maryland and Virginia suburbs of Washington, D.C.

Takoma Park's Metrorail station sits in the heart of the old downtown area, at the terminus of Carroll Street NW, main street of the Old Takoma area (continuing as Carroll Avenue in Maryland) on the D.C. side two blocks from the Maryland line. The Takoma Metro station is noted for having one of the highest pedestrian mode shares of any non-central business district station in the Washington Metrorail system.

New Hampshire Avenue is the only six-lane thoroughfare running through city limits, continuing into central Washington, D.C. and primarily serving through-traffic to the east of the city. Other major roads narrow to two lanes within city limits, including Route 410/East West Highway, a major state thoroughfare, and Piney Branch Road, which was narrowed from four lanes to two within city limits as a result of a traffic calming measure. The primary route into D.C. is Georgia Avenue, the main turnpike through downtown Silver Spring, and Blair Road, a two-lane road (formerly part of the Montgomery Blair estate) which becomes North Capitol Street, a six-lane boulevard to the south. University Boulevard, the major suburban shopping strip, skirts the area to the northeast. Carroll Avenue ends two miles short of the Washington Beltway/I-95 interchange.

While the 9-mile (14 km) Sligo Creek Trail is primarily used for recreation by bicyclists and pedestrians, the Rails-to-Trails Conservancy is sponsoring efforts to construct the Metropolitan Branch Trail, a rail trail in D.C. parallel to the Red Line, to connect Washington Union Station to Silver Spring and Bethesda, Maryland by way of the 12-mile (19 km) Capital Crescent Trail for bicycle commuting purposes.

Education

Primary and secondary schools

Public schools

The city is served by the Montgomery County Public Schools.

Elementary

Elementary schools that serve the city include:

- Piney Branch Elementary School (3-5)

- Rolling Terrace Elementary School (PK-5)

- Sligo Creek Elementary School (K-5)

- Takoma Park Elementary School (PK-2)

Most Takoma Park residents are zoned to Takoma Park ES and Piney Branch. Sligo Creek Elementary School has new boundaries that no longer include students living in Takoma Park. SCES has a French Immersion program open to all Montgomery County families via lottery.[58]

Middle

Middle schools that serve the city include:

- Silver Spring International Middle School

- Takoma Park Middle School (most Takoma Park residents are zoned to Takoma Park MS)

High

All of the city is served by Montgomery Blair High School.

Takoma Academy, a private high-school, is located in Takoma Park and is part of the Adventist Educational System.

With the Downcounty Consortium, students have limited opportunity to enroll in one of four other schools, including Kennedy, Northwood, Einstein, and Wheaton.

Colleges and universities

- Washington Adventist University, a private liberal arts university

- Montgomery College (Takoma Park/Silver Spring Campus) (a 2-year institution)

Nearby libraries

- Takoma Park Maryland Library is one of the few municipal libraries in suburban Maryland.

- Takoma Park Library, part of the District of Columbia Public Library system, was the first neighborhood library in Washington, D.C. and a Carnegie library.[59]

- Long Branch Library in Silver Spring is part of the Montgomery County Public Libraries.

See also

- Takoma, Washington, D.C.

- Benjamin Franklin Gilbert

- Category:People from Washington, D.C.

- List of cities in Maryland

References

- 1 2 "US Gazetteer files 2010". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2013-01-25.

- 1 2 "American FactFinder". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2013-01-25.

- ↑ "Population Estimates". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2014-07-07.

- ↑ "City of Takoma Park (About)". Official City Website. City of Takoma Park. Retrieved 2009-06-09.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Powers, Lindsay A. (May 14, 2013). "Takoma Park grants 16-year-olds right to vote". The Washington Post.

During its Monday meeting, the Takoma Park City Council passed a series of city charter amendments regarding its voting and election laws, including one allowing 16- and 17-year-olds to vote in city elections. ... With Monday’s vote, Takoma Park became the first city in the United States to lower its voting age — which was previously 18 — to 16.

- ↑ Bennett, Rebecca (January 6, 2015). "Council lowers Hyattsville voting age to 16 years old". Hyattsville Life & Times. Archived from the original on March 7, 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Proctor, John Claggett (1949). Proctor's Washington and Environs. John Clagett Proctor, LL.D. p. 331.

- ↑ Bright, William (2004). Native American Placenames of the United States. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. p. 469. ISBN 080613576X.

- ↑ Kohn, Diana (November 2008). "Takoma Park at 125" (PDF). Takoma Voice. pp. 14–15. Retrieved 2014-05-08.

- 1 2 3 4 "The History of Takoma Park". Washington Evening Star. June 15, 1889. p. 11.

- 1 2 3 4 "Along the Railroads". Washington Evening Star. August 22, 1885. p. 2.

- 1 2 3 "New Towns in Montgomery". The Baltimore Sun. August 23, 1888.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Proctor, John Claggett (1949). Proctor's Washington and Environs. John Clagett Proctor, LL.D. p. 335.

- ↑ "Improvements along the Metropolitan Branch". Washington Evening Star. February 9, 1889. p. 6.

- ↑ Horwitz, Sari (November 22, 1986). "Takoma Park Boasts Fast-Growing Values: From 'Tacky Park' to 'Chevy Chase East'". The Washington Post.

- ↑ Kaiman, Beth (June 29, 1989). "Takoma Park to Rally Round the Oak Leaf". The Washington Post.

- ↑ "The Takoma Park Election". Washington Evening Star. May 6, 1890. p. 8.

- ↑ Baist, G. William (1903). Baist's Real Estate Atlas Surveys of Washington, D.C., Volume 3, Plate 24.

- 1 2 3 "Seventh Day Adventists: Colonizing Largely in Takoma Park, Montgomery County". The Baltimore Sun. May 15, 1904. p. 11.

- ↑ "Deem Fire a Blessing: Why Seventh-day Adventists Moved to Washington". The Washington Post. May 9, 1904. p. 10.

- ↑ "Work of Adventists: Denomination Makes Washington Its Headquarters". The Washington Post. September 10, 1905.

- ↑ "Home for Adventists: Church Executives Perfecting Plans to Build Here". The Washington Post. October 8, 1903.

- 1 2 Pressley, Sue Anne (May 5, 1989). "Adventists' Move Marks End of Era: Takoma Park Losing 80-Year Neighbor". The Washington Post. p. C7.

- ↑ Hyer, Marjorie (August 29, 1981). "Seventh-Day Adventists Reeling From Financial, Theological Crises". The Washington Post. Toledo Blade, via Google News.

- ↑ DCist.com. "Takoma Park Votes to Impeach President Bush".

Commonly referred to as 'The People's Republic of Takoma Park' or 'The Berkeley of the East'

- ↑ Montgomery, David (August 23, 1995). "Casting Their Lots With Takoma Park: Three P.G. Neighborhoods Vote 211 to 93 to Join City". Washington Post.

- ↑ Montgomery, David (November 8, 1995). "In a Montgomery State of Mind, Takoma Park Votes to Unify". Washington Post.

- ↑ "Substantial Changes to Counties and County Equivalent Entities: 1970-Present". Census Bureau. Retrieved 8 August 2009.

- ↑ cf. Dan Robinson, City councilmember, et al.

- ↑ google book

- ↑ http://www.historictakoma.org/KidsA2ZGuide/c.htm

- ↑ "Annual Estimates of the Resident Population for Incorporated Places: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2015". Retrieved July 2, 2016.

- ↑ "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- ↑ "Annual Estimates of the Resident Population for Incorporated Places: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2014". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- 1 2 "2009-2013 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates: Selected Economic Characteristics: Takoma Park city, Maryland". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved November 11, 2015.

- ↑ "2009-2013 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates: Selected Social Characteristics: Takoma Park city, Maryland". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved November 11, 2015.

- ↑ "American FactFinder". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- ↑ http://www.gaydemographics.org/USA/states/maryland/2000Census_state_md_general.htm

- ↑ "Comprehensive Annual Financial Report, Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 2014" (PDF). City of Takoma Park. October 17, 2014. p. 97.

- ↑ http://tpff.org/09/about_organization.htm

- ↑ http://tpff.org/09/abouttpff.htm

- ↑ Takoma Park Independence Day Parade and Fireworks

- ↑ Meno, Mike. Grants offer hope for Takoma Theatre renewal. Maryland Gazette. 2008-07-16.

- ↑ Shay, Kevin. "Takoma group gets permit from FCC for radio station". Gazette.net. The Gazette. Retrieved 8 April 2015.

- ↑ Motorcycle riding cat dies

- ↑ Takoma Park, MD - Roscoe the Rooster

- ↑ About the Banjo Man - Frank Cassel

- ↑ http://blogs.nationaltrust.org/preservationnation/?p=2420

- ↑ "Exhibition Program". 2009-12-17.

- ↑ "Community Center Updates". Retrieved 2010-09-21.

- ↑ http://www.takomaparkmd.gov/code/Takoma_Park_Municipal_Code/Title_9/08/index.html

- ↑ http://www.takomaparkmd.gov/clerk/agenda/items/2007/010807-4.pdf Archived September 27, 2007, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Marimow, Ann E.; Spivack, Miranda S. (2008-07-10). "Takoma Park Officials Frown Upon Foie Gras". The Washington Post. Retrieved 2010-05-24.

- ↑ Takoma Park Nuclear Free Zone Act

- ↑ Zapana, Victor (June 19, 2012). "Takoma Park Grants Waiver to 'Nuclear-free Zone' Ordinance". The Washington Post.

- ↑ "Mayor Information Page". City of Takoma Park. Retrieved November 4, 2013.

- ↑ "Election Results, 1991 – 2012" (PDF). City of Takoma Park. November 6, 1991.

- ↑ Montgomery County Public Schools Maryland

- ↑ "Takoma Park Library History". Retrieved 2010-09-21.

External links

-

Media related to Takoma Park, Maryland at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Takoma Park, Maryland at Wikimedia Commons -

Takoma Park travel guide from Wikivoyage

Takoma Park travel guide from Wikivoyage -

Geographic data related to Takoma Park, Maryland at OpenStreetMap

Geographic data related to Takoma Park, Maryland at OpenStreetMap - Official website

- Historic Takoma

- Takoma Voice

- Takoma Foundation

- City of Takoma Park at the Wayback Machine (archived December 12, 1998)

- City of Takoma Park at the Wayback Machine (archived December 6, 1998)