Sun Tzu

| Sun Tzu | |

|---|---|

Statue of Sun Tzu in Yurihama, Tottori, in Japan | |

| Born |

544 BC (traditional) Qi state |

| Died | 496 BC (traditional) |

| Occupation | Military general and tactician |

| Ethnicity | Chinese |

| Period | Spring and Autumn |

| Subject | Military strategy |

| Notable works | The Art of War |

| Sun Tzu | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

"Sunzi" in ancient seal script (top), regular Traditional (middle), and Simplified (bottom) Chinese characters | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 孫子 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Simplified Chinese | 孙子 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | "Master Sun" | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sun Wu | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 孫武 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 孙武 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Changqing | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 長卿 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 长卿 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Sun Tzu (/ˈsuːnˈdzuː/;[2] also rendered as Sun Zi) was a Chinese general, military strategist, and philosopher who lived in the Spring and Autumn period of ancient China. Sun Tzu is traditionally credited as the author of The Art of War, a widely influential work of military strategy that has affected both Western and Eastern philosophy. Aside from his legacy as the author of The Art of War, Sun Tzu is revered in Chinese and the Culture of Asia as a legendary historical figure. His birth name was Sun Wu, and he was known outside of his family by his courtesy name Changqing. The name Sun Tzu by which he is best known in the West is an honorific which means "Master Sun."

Sun Tzu's historicity is uncertain. Sima Qian and other traditional historians placed him as a minister to King Helü of Wu and dated his lifetime to 544–496 BC. Modern scholars accepting his historicity nonetheless place the existing text of The Art of War in the later Warring States period based upon its style of composition and its descriptions of warfare.[3] Traditional accounts state that the general's descendant Sun Bin also wrote a treatise on military tactics, also titled The Art of War. Since both Sun Wu and Sun Bin were referred to as Sun Tzu in classical Chinese texts, some historians believed them identical prior to the rediscovery of Sun Bin's treatise in 1972.

Sun Tzu's work has been praised and employed throughout East Asia since its composition. During the twentieth century, The Art of War grew in popularity and saw practical use in Western society as well. It continues to influence many competitive endeavors in Asia, Europe, and America including culture, politics,[4][5] business,[6] and sports,[7] as well as modern warfare.

Life

The oldest available sources disagree as to where Sun Tzu was born. The Spring and Autumn Annals states that Sun Tzu was born in Qi,[8] while Sima Qian's later Records of the Grand Historian states that Sun Tzu was a native of Wu.[9] Both sources agree that Sun Tzu was born in the late Spring and Autumn period and that he was active as a general and strategist, serving king Helü of Wu in the late sixth century BC, beginning around 512 BC. Sun Tzu's victories then inspired him to write The Art of War. The Art of War was one of the most widely read military treatises in the subsequent Warring States period, a time of constant war among seven nations – Zhao, Qi, Qin, Chu, Han, Wei, and Yan – who fought to control the vast expanse of fertile territory in Eastern China.[10]

One of the more well-known stories about Sun Tzu, taken from Sima Qian, illustrates Sun Tzu's temperament as follows: Before hiring Sun Tzu, the King of Wu tested Sun Tzu's skills by commanding him to train a harem of 180 concubines into soldiers. Sun Tzu divided them into two companies, appointing the two concubines most favored by the king as the company commanders. When Sun Tzu first ordered the concubines to face right, they giggled. In response, Sun Tzu said that the general, in this case himself, was responsible for ensuring that soldiers understood the commands given to them. Then, he reiterated the command, and again the concubines giggled. Sun Tzu then ordered the execution of the king's two favored concubines, to the king's protests. He explained that if the general's soldiers understood their commands but did not obey, it was the fault of the officers. Sun Tzu also said that, once a general was appointed, it was his duty to carry out his mission, even if the king protested. After both concubines were killed, new officers were chosen to replace them. Afterwards, both companies, now well aware of the costs of further frivolity, performed their maneuvers flawlessly.[11]

Sima Qian claimed that Sun Tzu later proved on the battlefield that his theories were effective (for example, at the Battle of Boju), that he had a successful military career, and that he wrote The Art of War based on his tested expertise.[11] However, the Zuozhuan, a historical text written centuries earlier than the Records of the Grand Historian, provides a much more detailed account of the Battle of Boju, but does not mention Sun Tzu at all.[12]

Historicity

Beginning around the 12th century, some scholars began to doubt the historical existence of Sun Tzu, primarily on the grounds that he is not mentioned in the historical classic The Commentary of Zuo (Zuo zhuan 左傳), which mentions most of the notable figures from the Spring and Autumn period.[13] The name "Sun Wu" (孫武) does not appear in any text prior to the Records of the Grand Historian,[14] and may have been a made-up descriptive cognomen meaning "the fugitive warrior": the surname "Sun" can be glossed as the related term "fugitive" (xùn 遜), while "Wu" is the ancient Chinese virtue of "martial, valiant" (wǔ 武), which corresponds to Sunzi's role as the hero's doppelgänger in the story of Wu Zixu.[15] Skeptics cite possible historical inaccuracies and anachronisms in the text, and that the book was actually a compilation from different authors and military strategists. Attribution of the authorship of The Art of War varies among scholars and has included people and movements including Sun; Chu scholar Wu Zixu; an anonymous author; a school of theorists in Qi or Wu; Sun Bin; and others.[16] Unlike Sun Wu, Sun Bin appears to have been an actual person who was a genuine authority on military matters, and may have been the inspiration for the creation of the historical figure "Sunzi" through a form of euhemerism.[15] The name Sun Wu does appear in later sources such as the Records of the Grand Historian (Shiji 史記) and the Wu Yue chunqiu.[17] The only historical battle attributed to Sun Tzu, the Battle of Boju, has no record of him fighting in that battle.[18]

The appearance of features from The Art of War in other historical texts is considered to be proof of his historicity and authorship. Certain strategic concepts, such as terrain classification, are attributed to Sun Tzu. Their use in other works such as The Methods of the Sima is considered proof of Sun Tzu's historical priority.[19] According to Ralph Sawyer, it is very likely Sun Tzu did exist and not only served as a general but also wrote the core of the book that bears his name.[20] It is argued that there is a disparity between the large-scale wars and sophisticated techniques detailed in the text and the more primitive small-scale battles that many believe predominated in China during the 6th century BC. Against this, Sawyer argues that the teachings of Sun Wu were probably taught to succeeding generations in his family or a small school of disciples, which eventually included Sun Bin. These descendants or students may have revised or expanded upon certain points in the original text.[20]

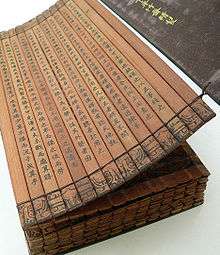

Skeptics who identify issues with the traditionalist view point to possible anachronisms in The Art of War including terms, technology (such as anachronistic crossbows and the unmentioned cavalry), philosophical ideas, events, and military techniques that should not have been available to Sun Wu.[21][22] Additionally, there are no records of professional generals during the Spring and Autumn period; these are only extant from the Warring States period, so there is doubt as to Sun Tzu's rank and generalship.[22] This caused much confusion as to when The Art of War was actually written. The first traditional view is that it was written in 512 BC by the historical Sun Wu, active in the last years of the Spring and Autumn period (c. 722-481 BC). A second view, held by scholars such as Samuel Griffith, places The Art of War during the middle to late Warring States period (c. 481-221 BC). Finally, a third school claims that the slips were published in the last half of the 5th century BC; this is based on how its adherents interpret the bamboo slips discovered at Yin-ch’ueh-shan in 1972 AD.[23]

The Art of War

The Art of War is traditionally ascribed to Sun Tzu. It presents a philosophy of war for managing conflicts and winning battles. It is accepted as a masterpiece on strategy and has been frequently cited and referred to by generals and theorists since it was first published, translated, and distributed internationally.[24]

There are numerous theories concerning when the text was completed and concerning the identity of the author or authors, but archeological recoveries show The Art of War had taken roughly its current form by at least the early Han.[25] Because it is impossible to prove definitively when the Art of War was completed before this date, the differing theories concerning the work's author or authors and date of completion are unlikely to be completely resolved.[26] Some modern scholars believe that it contains not only the thoughts of its original author but also commentary and clarifications from later military theorists, such as Li Quan and Du Mu.

Of the military texts written before the unification of China and Shi Huangdi's subsequent book burning in the second century BC, six major works have survived. During the much later Song dynasty, these six works were combined with a Tang text into a collection called the Seven Military Classics. As a central part of that compilation, The Art of War formed the foundations of orthodox military theory in early modern China. Illustrating this point, the book was required reading to pass the tests for imperial appointment to military positions.[27]

Sun Tzu's Art of War uses language that may be unusual in a Western text on warfare and strategy.[28] For example, the eleventh chapter states that a leader must be "serene and inscrutable" and capable of comprehending "unfathomable plans". The text contains many similar remarks that have long confused Western readers lacking an awareness of the East Asian context. The meanings of such statements are clearer when interpreted in the context of Taoist thought and practice. Sun Tzu viewed the ideal general as an enlightened Taoist master, which has led to The Art of War being considered a prime example of Taoist strategy.

The book has also become popular among political leaders and those in business management. Despite its title, The Art of War addresses strategy in a broad fashion, touching upon public administration and planning. The text outlines theories of battle, but also advocates diplomacy and the cultivation of relationships with other nations as essential to the health of a state.[24]

On April 10, 1972, the Yinqueshan Han Tombs were accidentally unearthed by construction workers in Shandong.[29][30] Scholars uncovered a collection of ancient texts written on unusually well-preserved bamboo slips. Among them were The Art of War and Sun Bin's Military Methods.[30] Although Han dynasty bibliographies noted the latter publication as extant and written by a descendant of Sun, it had previously been lost. The rediscovery of Sun Bin's work is regarded as extremely important by scholars, both because of Sun Bin's relationship to Sun Tzu and because of the work's addition to the body of military thought in Chinese late antiquity.[31] The discovery as a whole significantly expanded the body of surviving Warring States military theory. Sun Bin's treatise is the only known military text surviving from the Warring States period discovered in the twentieth century and bears the closest similarity to The Art of War of all surviving texts.

Legacy

Sun Tzu's Art of War has influenced many notable figures. Sima Qian recounted that China's first historical emperor, Qin's Shi Huangdi, considered the book invaluable in ending the time of the Warring States. In the 20th century, the Chinese Communist leader Mao Zedong partially credited his 1949 victory over Chiang Kai-shek and the Kuomintang to The Art of War. The work strongly influenced Mao's writings about guerrilla warfare, which further influenced communist insurgencies around the world.[32]

The Art of War was introduced into Japan c. AD 760 and the book quickly became popular among Japanese generals. Through its later influence on Oda Nobunaga, Toyotomi Hideyoshi, and Tokugawa Ieyasu,[32] it significantly affected the unification of Japan in the early modern era. Prior to the Meiji Restoration, mastery of its teachings was honored among the samurai and its teachings were both exhorted and exemplified by influential daimyo and shoguns. Subsequently, it remained popular among the Imperial Japanese armed forces. The Admiral of the Fleet Tōgō Heihachirō, who led Japan's forces to victory in the Russo-Japanese War, was an avid reader of Sun Tzu.[33]

Ho Chi Minh translated the work for his Vietnamese officers to study. His general Vo Nguyen Giap, the strategist behind victories over French and American forces in Vietnam, was likewise an avid student and practitioner of Sun Tzu's ideas.[34][35][36]

America's Asian conflicts against Japan, North Korea, and North Vietnam brought Sun Tzu to the attention of American military leaders. The Department of the Army in the United States, through its Command and General Staff College, has directed all units to maintain libraries within their respective headquarters for the continuing education of personnel in the art of war. The Art of War is mentioned as an example of works to be maintained at each facility, and staff duty officers are obliged to prepare short papers for presentation to other officers on their readings.[37] Similarly, Sun Tzu's Art of War is listed on the Marine Corps Professional Reading Program.[38] During the Gulf War in the 1990s, both Generals Norman Schwarzkopf Jr. and Colin Powell employed principles from Sun Tzu related to deception, speed, and striking one's enemy's weak points.[32] However, the United States and other Western countries have been criticised for not truly understanding Sun Tzu's work and not appreciating The Art of War within the wider context of Chinese society.[39]

Daoist rhetoric is a component incorporated in the Art of War. According to Steven C. Combs in "Sun-zi and the Art of War: The Rhetoric of Parsimony",[40] warfare is "used as a metaphor for rhetoric, and that both are philosophically based arts."[40] Combs writes "Warfare is analogous to persuasion, as a battle for hearts and minds."[40] The application of The Art of War strategies throughout history is attributed to its philosophical rhetoric. Daoism is the central principle in the Art of War. Combs compares ancient Daoist Chinese to traditional Aristotelian rhetoric, notably for the differences in persuasion. Daoist rhetoric in the art of war warfare strategies is described as "peaceful and passive, favoring silence over speech".[40] This form of communication is parsimonious. Parsimonious behavior, which is highly emphasized in The Art of War as avoiding confrontation and being spiritual in nature, shapes basic principles in Daoism.[41]

Mark McNeilly writes in Sun Tzu and the Art of Modern Warfare that a modern interpretation of Sun and his importance throughout Chinese history is critical in understanding China's push to becoming a superpower in the twenty-first century. Modern Chinese scholars explicitly rely on historical strategic lessons and The Art of War in developing their theories, seeing a direct relationship between their modern struggles and those of China in Sun Tzu's time. There is a great perceived value in Sun Tzu's teachings and other traditional Chinese writers, which are used regularly in developing the strategies of the Chinese state and its leaders.[42]

In 2008, producer Zhang Jizhong adapted Sun Tzu's life story into a 40-episode historical drama television series entitled Bing Sheng, starring Zhu Yawen as Sun Tzu.[43]

Notes

- ↑ Baxter, William H. & Sagart, Laurent (2011), Baxter–Sagart Old Chinese Reconstruction, retrieved 18 August 2013.

- ↑ "Sun Tzu". Columbia Electronic Encyclopedia (2013).

- ↑ Sawyer, Ralph D. (2007), The Seven Military Classics of Ancient China, New York: Basic Books, pp. 421–422, ISBN 0-465-00304-4.

- ↑ Scott, Wilson (7 March 2013), "Obama meets privately with Jewish leaders", The Washington Post, Washington, DC, retrieved 22 May 2013.

- ↑ "Obama to challenge Israelis on peace", United Press International, 8 March 2013, retrieved 22 May 2013.

- ↑ Garner, Rochelle (16 October 2006), "Oracle's Ellison Uses 'Art of War' in Software Battle With SAP", Bloomberg, retrieved 18 May 2013.

- ↑ Hack, Damon (3 February 2005), "For Patriots' Coach, War Is Decided Before Game", The New York Times, retrieved 18 May 2013.

- ↑ Sawyer 2007, p. 151.

- ↑ Sawyer 2007, p. 153.

- ↑ McNeilly 2001, pp. 3–4.

- 1 2 Bradford 2000, pp. 134–135.

- ↑ Zuo Qiuming, "Duke Ding", Zuo Zhuan (in Chinese and English), XI, retrieved 30 November 2011.

- ↑ Gawlikowski & Loewe (1993), p. 447.

- ↑ Mair (2007), p. 9.

- 1 2 Mair, Victor H. (2007). The Art of War: Sun Zi's Military Methods. New York: Columbia University Press. pp. 9-10. ISBN 978-0-231-13382-1.

- ↑ Sawyer 2005, pp. 34–35.

- ↑ Sawyer 2007, pp. 176–177.

- ↑ Worthington, Daryl. "The Art of War". New Historian. March 13, 2015

- ↑ Sawyer 1994, pp. 149–150.

- 1 2 Sawyer 2007, pp. 150–151.

- ↑ Yang, Sang. The Art of War. Wordsworth Editions Ltd (December 5, 1999). pp. 14-15. ISBN 978-1853267796

- 1 2 Szczepanski, Kallie. "Sun Tzu and the Art of War". Asian History. February 04, 2015

- ↑ Morrow, Nicholas. "Sun Tzu, The Art of War (c. 500-300 B.C.)". Classics of Strategy. February 04, 2015

- 1 2 McNeilly 2001, p. 5.

- ↑ Sawyer 2007, p. 423.

- ↑ Sawyer 2007, p. 150.

- ↑ Sawyer 1994, pp. 13–14.

- ↑ Simpkins & Simpkins 1999, pp. 131–33.

- ↑ Yinqueshan Han Bamboo Slips (in Chinese), Shandong Provincial Museum, 24 April 2008.

- 1 2 Clements, Jonathan (21 June 2012), The Art of War: A New Translation, Constable & Robinson Ltd, pp. 77–78, ISBN 978-1-78033-131-7.

- ↑ 朱文章(Sydney Wen-Jang Chu) ; 李承禹(Cheng-Yu Lee) Just another Masterpiece: the Differences between Sun Tzu's the Art of War and Sun Bin's the Art of War. http://www.airitilibrary.com/Publication/alDetailedMesh?docid=P20121108003-201301-201302010022-201302010022-59-73

- 1 2 3 McNeilly 2001, pp. 6–7.

- ↑ Tung 2001, p. 805.

- ↑ "Interview with Dr. William Duiker", Sonshi.com, retrieved 5 February 2011.

- ↑ "Learning from Sun Tzu", Military Review, May–June 2003.

- ↑ Forbes, Andrew & Henley, David (2012), The Illustrated Art of War: Sun Tzu, Chiang Mai: Cognoscenti Books, ASIN B00B91XX8U.

- ↑ U.S. Army (c. 1985), Military History and Professional Development, U.S. Army Command and General Staff College, Fort Leavenworth, Kansas: Combat Studies Institute, 85-CSI-21 85. The Art of War is mentioned for each unit's acquisition in "Military History Libraries for Duty Personnel" on page 18.

- ↑ "Marine Corps Professional Reading Program", U.S. Marine Corps.

- ↑ Hall, Gavin. "Review - Deciphering The Art of War". LSE Review of Books. Retrieved 23 March 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 Combs, Steven C. (August 2000). "Sun-zi and the Art of War: The Rhetoric of Parsimony". Quarterly Journal of Speech. 3: 276–294. doi:10.1080/00335630009384297.

- ↑ Galvany, Albert (October 2011). "Philosophy, Biography, and Anecdote: On the Portrait of Sun Wu". Philosophy East and West. 61 (4): 630–646. doi:10.1353/pew.2011.0059.

- ↑ McNeilly 2001, p. 7.

- ↑ Bing Sheng (in Chinese), sina.com.

References

- Bradford, Alfred S. (2000), With Arrow, Sword, and Spear: A History of Warfare in the Ancient World, Praeger Publishers, ISBN 0-275-95259-2.

- Gawlikowski, Krzysztof; Loewe, Michael (1993). "Sun tzu ping fa 孫子兵法". In Loewe, Michael. Early Chinese Texts: A Bibliographical Guide. Berkeley: Society for the Study of Early China; Institute of East Asian Studies, University of California, Berkeley. pp. 446–55. ISBN 1-55729-043-1.

- McNeilly, Mark R. (2001), Sun Tzu and the Art of Modern Warfare, Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-513340-4.

- Mair, Victor H. (2007). The Art of War: Sun Zi's Military Methods. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-13382-1.

- Sawyer, Ralph D. (1994), The Art of War, Westview Press, ISBN 0-8133-1951-X.

- Sawyer, Ralph D. (2005), The Essential Art of War, Basic Books, ISBN 0-465-07204-6.

- Sawyer, Ralph D. (2007), The Seven Military Classics of Ancient China, Basic Books, ISBN 0-465-00304-4.

- Simpkins, Annellen & Simpkins, C. Alexander (1999), Taoism: A Guide to Living in the Balance, Tuttle Publishing, ISBN 978-0-8048-3173-4.

- Tao, Hanzhang; Wilkinson, Robert (1998), The Art of War, Wordsworth Editions, ISBN 978-1-85326-779-6.

- Tung, R.L. (2001), "Strategic Management Thought in East Asia", in Warner, Malcolm, Comparative Management:Critical Perspectives on Business and Management, 3, Routledge, ISBN 0-415-13263-0.

External links

- Translations

- Works by Sun Tzu at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Sun Tzu at Internet Archive

- Works by Sun Tzu at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Sun Tzu's Art of War at Sonshi

- Sun Tzu and Information Warfare at the Institute for National Strategic Studies of National Defense University

- Sun Tzu sites

- Sun Tzu's Art of War Sonshi.com. Reviews of translations, interviews with translators, notices of activities.

- Sun Tzu DMOZ Open Directory Project Collection of links to online translations and resources on Sun Tzu.

- Victory Over War Formed by the Denma Group to supplement their translation with notes, reviews, and discussion.

.svg.png)