String searching algorithm

In computer science, string searching algorithms, sometimes called string matching algorithms, are an important class of string algorithms that try to find a place where one or several strings (also called patterns) are found within a larger string or text.

Let Σ be an alphabet (finite set). Formally, both the pattern and searched text are vectors of elements of Σ. The Σ may be a usual human alphabet (for example, the letters A through Z in the Latin alphabet). Other applications may use binary alphabet (Σ = {0,1}) or DNA alphabet (Σ = {A,C,G,T}) in bioinformatics.

In practice, how the string is encoded can affect the feasible string search algorithms. In particular if a variable width encoding is in use then it is slow (time proportional to N) to find the Nth character. This will significantly slow down many of the more advanced search algorithms. A possible solution is to search for the sequence of code units instead, but doing so may produce false matches unless the encoding is specifically designed to avoid it.

Basic classification

The various algorithms can be classified by the number of patterns each uses.

Single pattern algorithms

Let m be the length of the pattern, n be the length of the searchable text and k = |Σ| be the size of the alphabet.

| Algorithm | Preprocessing time | Matching time |

|---|---|---|

| Naïve string search algorithm | 0 (no preprocessing) | Θ(nm) |

| Rabin–Karp string search algorithm | Θ(m) | average Θ(n + m), worst Θ((n−m)m) |

| Finite-state automaton based search | Θ(mk) | Θ(n) |

| Knuth–Morris–Pratt algorithm | Θ(m) | Θ(n) |

| Boyer–Moore string search algorithm | Θ(m + k) | best Ω(n/m), worst O(mn) |

| Bitap algorithm (shift-or, shift-and, Baeza–Yates–Gonnet) | Θ(m + k) | O(mn) |

| Two-way string-matching algorithm | Θ(m) | O(n+m) |

| BNDM (Backward Non-Deterministic Dawg Matching) | O(m) | O(n) |

| BOM (Backward Oracle Matching) | O(m) | O(n) |

- 1.^ Asymptotic times are expressed using O, Ω, and Θ notation.

The Boyer–Moore string search algorithm has been the standard benchmark for the practical string search literature.[1]

Algorithms using a finite set of patterns

- Aho–Corasick string matching algorithm (extension of Knuth-Morris-Pratt)

- Commentz-Walter algorithm (extension of Boyer-Moore)

- Set-BOM (extension of Backward Oracle Matching)

- Rabin–Karp string search algorithm

Algorithms using an infinite number of patterns

Naturally, the patterns can not be enumerated finitely in this case. They are represented usually by a regular grammar or regular expression.

Other classification

Other classification approaches are possible. One of the most common uses preprocessing as main criteria.

| Text not preprocessed | Text preprocessed | |

|---|---|---|

| Patterns not preprocessed | Elementary algorithms | Index methods |

| Patterns preprocessed | Constructed search engines | Signature methods |

Another one classifies the algorithms by their matching strategy:[3]

- Match the prefix first (Knuth-Morris-Pratt, Shift-And, Aho-Corasick)

- Match the suffix first (Boyer-Moore and variants, Commentz-Walter)

- Match the best factor first (BNDM, BOM, Set-BOM)

- Other strategy (Naive, Rabin-Karp)

Naïve string search

A simple but inefficient way to see where one string occurs inside another is to check each place it could be, one by one, to see if it's there. So first we see if there's a copy of the needle in the first character of the haystack; if not, we look to see if there's a copy of the needle starting at the second character of the haystack; if not, we look starting at the third character, and so forth. In the normal case, we only have to look at one or two characters for each wrong position to see that it is a wrong position, so in the average case, this takes O(n + m) steps, where n is the length of the haystack and m is the length of the needle; but in the worst case, searching for a string like "aaaab" in a string like "aaaaaaaaab", it takes O(nm)

Finite state automaton based search

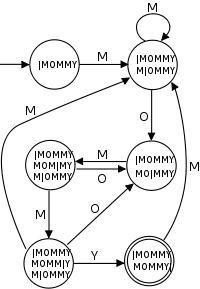

In this approach, we avoid backtracking by constructing a deterministic finite automaton (DFA) that recognizes stored search string. These are expensive to construct—they are usually created using the powerset construction—but are very quick to use. For example, the DFA shown to the right recognizes the word "MOMMY". This approach is frequently generalized in practice to search for arbitrary regular expressions.

Stubs

Knuth–Morris–Pratt computes a DFA that recognizes inputs with the string to search for as a suffix, Boyer–Moore starts searching from the end of the needle, so it can usually jump ahead a whole needle-length at each step. Baeza–Yates keeps track of whether the previous j characters were a prefix of the search string, and is therefore adaptable to fuzzy string searching. The bitap algorithm is an application of Baeza–Yates' approach.

Index methods

Faster search algorithms are based on preprocessing of the text. After building a substring index, for example a suffix tree or suffix array, the occurrences of a pattern can be found quickly. As an example, a suffix tree can be built in time, and all occurrences of a pattern can be found in time under the assumption that the alphabet has a constant size and all inner nodes in the suffix tree know what leaves are underneath them. The latter can be accomplished by running a DFS algorithm from the root of the suffix tree.

Other variants

Some search methods, for instance trigram search, are intended to find a "closeness" score between the search string and the text rather than a "match/non-match". These are sometimes called "fuzzy" searches.

See also

References

- ↑ Hume; Sunday (1991). "Fast String Searching". Software: Practice and Experience. 21 (11): 1221–1248. doi:10.1002/spe.4380211105.

- ↑ Melichar, Borivoj, Jan Holub, and J. Polcar. Text Searching Algorithms. Volume I: Forward String Matching. Vol. 1. 2 vols., 2005. http://stringology.org/athens/TextSearchingAlgorithms/.

- ↑ Gonzalo Navarro; Mathieu Raffinot (2008), Flexible Pattern Matching Strings: Practical On-Line Search Algorithms for Texts and Biological Sequences, ISBN 0-521-03993-2

- R. S. Boyer and J. S. Moore, A fast string searching algorithm, Carom. ACM 20, (10), 262–272(1977).

- Thomas H. Cormen, Charles E. Leiserson, Ronald L. Rivest, and Clifford Stein. Introduction to Algorithms, Third Edition. MIT Press and McGraw-Hill, 2009. ISBN 0-262-03293-7. Chapter 32: String Matching, pp. 985-1013.

External links

- Huge (maintained) list of pattern matching links Last updated:12/27/2008 20:18:38

- StringSearch – high-performance pattern matching algorithms in Java – Implementations of many String-Matching-Algorithms in Java (BNDM, Boyer-Moore-Horspool, Boyer-Moore-Horspool-Raita, Shift-Or)

- StringsAndChars – Implementations of many String-Matching-Algorithms (for single and multiple patterns) in Java

- Exact String Matching Algorithms — Animation in Java, Detailed description and C implementation of many algorithms.

- (PDF) Improved Single and Multiple Approximate String Matching

- Kalign2: high-performance multiple alignment of protein and nucleotide sequences allowing external features

- C implementation of Suffix Tree based Pattern Searching