State Opening of Parliament

.svg.png) |

| This article is part of a series on the politics and government of the United Kingdom |

|

|

|

|

The State Opening of Parliament is an event which formally marks the beginning of a session of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. It includes a speech from the throne known as the Queen's Speech (or King's Speech). The State Opening is an elaborate ceremony showcasing British history, culture and contemporary politics to large crowds and television viewers.

It takes place in the House of Lords chamber, usually in May or June, in front of both Houses of Parliament. The monarch, wearing the Imperial State Crown, reads a speech that has been prepared by his or her government outlining its plans for that year. A State Opening may take place at other times of the year if an election is held early due to a vote of no confidence in the government. In 1974, when two general elections were held, there were two State Openings.

Queen Elizabeth II has opened every session of Parliament since her accession, except in 1959 and 1963 when she was pregnant with Prince Andrew and Prince Edward respectively. Those two sessions were opened by Lords Commissioners, headed by the Archbishop of Canterbury (Geoffrey Fisher in 1959 and Michael Ramsey in 1963), empowered by the Queen. The Lord Chancellor (Viscount Kilmuir in 1959 and Lord Dilhorne in 1963) read the Queen's Speech on those occasions.

Sequence of events

The State Opening is a lavish ceremony of several parts:

Searching of the cellars

First, the cellars of the Palace of Westminster are searched by the Yeomen of the Guard in order to prevent a modern-day Gunpowder Plot. The Plot of 1605 involved a failed attempt by a group of provincial English Catholics led by Robert Catesby to blow up the Houses of Parliament and kill the Protestant King James I and aristocracy. Since that year, the cellars have been searched, now largely, but not only, for ceremonial purposes.

Assembly of Peers and Commons

The peers assemble in the House of Lords wearing their robes. They are joined by senior representatives of the judiciary and members of the diplomatic corps. The Commons assemble in their own chamber, wearing ordinary day dress, and begin the day, as any other, with prayers.

Delivery of Parliamentary hostage

Before the monarch departs Buckingham Palace the Treasurer, Comptroller and Vice-Chamberlain of the Queen's Household (all of whom are Government whips) deliver ceremonial white staves to her.[1] The Queen keeps the Vice-Chamberlain 'prisoner' for the duration of the state opening as insurance for the safe return of the monarch, though he is well entertained until the successful conclusion of the ceremony,[1] when he is released. The Vice-Chamberlain's imprisonment is now purely ceremonial, though he does remain under guard; originally, it guaranteed the safety of the Sovereign as he or she entered a possibly hostile Parliament. The tradition stems from the time of Charles I, who had a contentious relationship with Parliament and was eventually beheaded in 1649 during the Civil War between the monarchy and Parliament. A copy of Charles I's death warrant is displayed in the robing room used by the Queen as a ceremonial reminder of what can happen to a Monarch who attempts to interfere with Parliament.

Arrival of Royal Regalia

Before the arrival of the sovereign, the Imperial State Crown is carried to the Palace of Westminster in its own State Coach. From the Victoria Tower, the Crown is passed by the Queen's Bargemaster to the Comptroller of the Lord Chamberlain's office. It is then carried, along with the Great Sword of State and the Cap of Maintenance, to be displayed in the Royal Gallery.

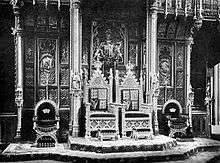

Arrival of the Sovereign and assembly of Parliament

The Queen arrives from Buckingham Palace at the Palace of Westminster in a horse-drawn coach, entering through the Sovereign's Entrance under the Victoria Tower; she is accompanied by her consort The Duke of Edinburgh (though their son The Prince of Wales has deputised for his father) and sometimes by other members of the royal family, such as The Prince of Wales and The Duchess of Cornwall or The Princess Royal. Traditionally, members of the armed forces line the procession route from Buckingham Palace to the Palace of Westminster. The Royal Standard is hoisted to replace the Union Flag upon the Sovereign's entrance and remains flying whilst she is in attendance. Then, after she takes on the Parliament Robe of State[2][3] and Imperial State Crown in the Robing Chamber, the Queen proceeds through the Royal Gallery to the House of Lords, usually accompanied by the Duke of Edinburgh and immediately preceded by the Earl Marshal, and by one peer (usually the Leader of the House of Lords) carrying the Cap of Maintenance on a white rod, and another peer (generally a retired senior military officer) carrying the Great Sword of State, all following the Lord Great Chamberlain and his white stick, commonly the practical implement of ceremonial ushers, raised aloft. Once seated on the throne, the Queen, wearing the Imperial State Crown, instructs the House by saying, "My Lords, pray be seated."; her consort takes his seat on the throne to her left and other members of the Royal family may be seated elsewhere on the dais (for instance the Prince of Wales and Duchess of Cornwall are seated on thrones on a lower portion of the dais to the Queen's right.)

Royal summons to the Commons

Motioned by the Monarch, the Lord Great Chamberlain raises his wand of office to signal to the Gentleman Usher of the Black Rod (known as Black Rod), who is charged with summoning the House of Commons and has been waiting in the Commons lobby. Black Rod turns and, under the escort of the Door-keeper of the House of Lords and a police inspector (who orders "Hats off, Strangers!" to all persons along the way), approaches the doors to the Chamber of the Commons.

In 1642, King Charles I stormed into the House of Commons in an unsuccessful attempt to arrest the Five Members, which included the celebrated English patriot and leading parliamentarian John Hampden.[4][5] Since that time, no British monarch has entered the House of Commons when it is sitting [meeting].[6]

On Black Rod's approach, the doors are slammed shut against him, symbolising the rights of parliament and its independence from the monarch.[6] He then strikes with the end of his ceremonial staff (the Black Rod) three times on the closed doors of the Commons Chamber, and is then admitted. (There is a mark on the door of the Commons showing the repeated indentations made by Black Rods over the years.) At the bar, Black Rod bows to the speaker before proceeding to the dispatch box where he announces the command of the monarch for the attendance of the Commons, in the following words:

"Mr (or Madam) Speaker, The Queen commands this honourable House [pauses to bow to both sides of the House] to attend Her Majesty immediately in the House of Peers."

By unofficial tradition, in recent years, this has been greeted with a defiant topical comment by republican-leaning Labour MP Dennis Skinner, upon which, with some mirth, the House rises to make its way to the Lords' Chamber.[6] This customary intervention was not observed by Mr Skinner in 2015, claiming that he had "bigger fish to fry than uttering something," due to a dispute over seating with the Scottish Nationalists.[7]

Procession of the Commons

The Speaker proceeds to attend the summons at once. The Serjeant-at-Arms picks up the ceremonial mace and, with the Speaker and Black Rod, leads the Members of the House of Commons as they walk, in pairs, towards the House of Lords. By custom, the members saunter, with much discussion and joking, rather than formally process. The Prime Minister and the Leader of the Opposition followed by The Deputy Prime Minister and the Deputy Leader of the Opposition usually walk side by side, leading the two lines of MPs. The Commons then arrive at the Bar of the House of Lords where they bow to the Queen. No person who is not a member of the Upper House may pass the Bar unbidden when it is in session; a similar rule applies to the Commons. They remain standing at the Bar during the speech.

Delivery of the speech

The Queen reads a prepared speech, known as the "Speech from the Throne" or the "Queen's Speech", outlining the Government's agenda for the coming year. The speech is written by the Prime Minister and his cabinet members, and reflects the legislative agenda for which the Government seeks the agreement of both Houses of Parliament. It is traditionally written on goatskin vellum, and presented on bended knee for the Queen to read by the Lord Chancellor, who produces the scroll from a satchel-like bag. Traditionally, rather than turning his back on the Sovereign, which might appear disrespectful, the Lord Chancellor walks backwards down the steps of the throne, continuing to face the monarch. Lord Irvine of Lairg, the Lord Chancellor appointed by Prime Minister Tony Blair, sought to break the custom and applied successfully for permission to turn his back on The Queen and walk down the steps forwards, but the next Lord Chancellor Jack Straw continued the former tradition.

The whole speech is addressed to "My Lords and Members of the House of Commons", with one significant exception that the Queen says specifically, "Members of the House of Commons, estimates for the public services will be laid before you", since the budget is constitutionally reserved to the Commons.

The Queen reads the entire speech in a neutral and formal tone, implying neither approval nor disapproval of the proposals of Her Majesty's Government: the Queen makes constant reference to "My Government" when reading the text. After listing the main bills to be introduced during the session, the Queen states: "other measures will be laid before you", thus leaving the Government scope to introduce bills not mentioned in the speech. The Queen mentions any State Visits that she intends to make and also any planned State Visits of foreign Heads of State to the United Kingdom during the Parliamentary session. The Queen concludes the speech in saying:

"My Lords and Members of the House of Commons, I pray that the blessing of Almighty God may rest upon your counsels".

Traditionally, the members of both Houses of Parliament listen to the Queen's Speech respectfully, neither applauding nor showing dissent towards the speech's contents before it is debated in each House. This silence, however, was broken in 1998, when the Queen announced the Government's plan of abolishing the right of hereditary peers to sit in the House of Lords. A few Labour members of the House of Commons cried "yes" and "hear", prompting several of the Lords to shout "no" and "shame". The Queen continued delivering her speech without any pause, ignoring the intervention. The conduct of those who interrupted the speech was highly criticised at the time.[8][9]

Departure of monarch

Following the speech, the Queen leaves the chamber before the Commons bow again and return to their Chamber.

Debate on the speech

After the departure of the Queen, each Chamber proceeds to the consideration of an "Address in Reply to Her Majesty's Gracious Speech." But first, each House considers a bill pro forma to symbolise their right to deliberate independently of the monarch. In the House of Lords, the bill is called the Select Vestries Bill, while the Commons equivalent is the Outlawries Bill. The Bills are considered for the sake of ceremony only, and do not make any actual legislative progress. The first speech of the debate in the Commons is, by tradition, a humorous one given by a member selected in advance. The consideration of the address in reply to the Throne Speech is the occasion for a debate on the Government's agenda. The debate on the Address in Reply is spread over several days. On each day, a different topic, such as foreign affairs or finance, is considered. The debate provides an indication of the views of Parliament regarding the government's agenda.

Significance

The State Opening of Parliament is a ceremony loaded with historical ritual and symbolic significance for the governance of the United Kingdom. In one place are assembled the members of all three branches of government, of which the Monarch is the nominal head in each case: the Crown-in-Parliament, (the Queen, together with the House of Commons and the House of Lords), constitutes the legislature; Her Majesty's Ministers (who are members of one or other House) constitute the executive; Her Majesty's Judges, although not members of either House, are summoned to attend and represent the judiciary. Therefore, the State Opening demonstrates the governance of the United Kingdom but also the separation of powers. The importance of international relations is also represented through the presence in the Chamber of the Corps Diplomatique.

Origins

The Opening of Parliament[10] began out of practical necessity. By the late fourteenth century, the means by which the King gathered his nobles and representatives of the Commons had begun to follow an established pattern. First of all, Peers' names were checked against the list of those who had been summoned, and representatives of the Commons were checked against the sheriffs' election returns. The Peers were robed and sat in the Painted Chamber at Westminster; the Commons were summoned, and stood at the Bar (threshold) of the Chamber. A speech or sermon was then given (usually by the Lord Chancellor) explaining why Parliament had been summoned, after which the Lords and Commons went separately to discuss the business in hand. The monarch normally presided, not only for the Opening but also for the deliberations which followed (unless prevented by illness or other pressing matters).

In the Tudor period, the modern structure of Parliament began to emerge, and the monarch no longer attended during normal proceedings. For this reason, the State Opening took on greater symbolic significance as an occasion for the full constitution of the State (Monarch, Lords and Commons) to be seen. In this period, the parliamentary gathering began to be preceded by an open-air State Procession (which often attracted large numbers of onlookers): the Monarch, together with Household retinue, would proceed in State from whichever royal residence was being used, first to Westminster Abbey for a service (usually a Mass of the Holy Ghost, prior to the Reformation), and thence on foot (accompanied by the Lords Spiritual and Temporal in their robes) to the Palace of Westminster for the Opening itself.

A contemporary illustration[11] of the 1523 State Opening shows a remarkable visual similarity between State Openings of the 16th and 21st centuries. In both cases, the monarch sits on a throne before the Cloth of Estate, crowned and wearing a crimson robe of state; the Cap of Maintenance and Sword of State are borne by peers standing before the monarch on the left and right respectively; the Lord Great Chamberlain stands alongside, bearing his white wand of office. Members of the Royal retinue are arrayed behind the King (top right). In the main body of the Chamber, the Bishops are seated on benches to the King's right wearing their parliamentary robes, and the Lords Temporal are seated on the other benches (among them the Duke of Norfolk, carrying his baton as Earl Marshal of England). The judges (red-robed and coifed) are on the woolsacks in the centre, and behind them are the clerks (with quills and inkpots). At the bottom of the picture members of the House of Commons can be seen at the Bar to the House, with the Speaker in the centre, wearing his black and gold robe of state.

Since that time the ceremonial has evolved, but not dramatically. Mitred Abbots (who are to be seen, black-robed, in the 1523 illustration) were removed from Parliament at the time of the Reformation. In 1679 neither the procession nor the Abbey service took place, due to fears of a Popish Plot; although the procession was subsequently restored, the service in the Abbey was not. The monarch's role in the proceedings changed over time: early on, the monarch would say some introductory words, before calling upon the Lord Chancellor (or Lord Keeper) to address the assembly. James I, however, was accustomed to speak at greater length himself, and sometimes dispensed with the Chancellor's services as spokesman. This varying pattern continued in subsequent reigns (and during the Commonwealth, when Cromwell gave the speech), but from 1679 onwards it became the norm for the monarch alone to speak. Since then, the monarch (if present) has almost invariably given the speech, with the exception of George I (whose command of English was poor) and Victoria (after the death of Prince Albert). A dramatic change was occasioned by the destruction of the old Palace of Westminster by fire in 1834; however, the new palace was designed with the ceremony of the State Opening very much in mind,[12] and the modern ceremony dates from its opening in 1852.[13] The entire State Opening of Parliament was filmed for the first time in 1958.[14] In 1998, adjustments were made and some participants were dropped.[15]

Equivalents in other countries

Similar ceremonies are held in other Commonwealth realms. The governor-general or, in the case of Australia's states and Canada's provinces, the relevant governor or lieutenant governor, respectively, usually delivers the Speech from the Throne. On occasion, the monarch may open these parliaments (except those of the Canadian provinces) and deliver the speech herself.

In India, the President of India opens Parliament with an address similar to the Speech from the Throne. This is also the case in Commonwealth Republics with a non-executive Presidency such as Malta, Mauritius and Singapore.

In the Netherlands a similar ceremony is held on the third Tuesday in September, which is called Prinsjesdag in the Netherlands. In Sweden a similar ceremony as the British was held until 1974, when the constitution was changed. The old opening of state was in Sweden called Riksdagens högtidliga öppnande ("The solemn opening of the Riksdag") and was, as the British, full of symbolism. After the abolition of the old state opening, the opening is now held in the Riksdag but in the presence of the monarch and his family. It is still the King who officially opens the parliament. After the opening of parliament the King gives a speech followed by the Prime Minister's declaration of government. In Israel, a semi-annual ceremony, attended by the President, opens the winter and summer sessions of the Knesset. Though in the past he was a guest sitting in the Knesset's upper deck, the President now attends the ceremony from the speaker's podium and gives his own written address regarding the upcoming session. In the first session of each legislative period of the Knesset, the President has the duty of opening the first session himself and inaugurating the temporary Knesset speaker, and then conducting the inauguration process of all of the Knesset members.

In Norway, the King is required by Article 74 of the constitution to preside over the opening of the Storting after it had been declared to be legally constituted by the president of the Storting. After he delivers the Speech from the Throne, outlining the government's policies for the coming year, a member of the government reads the Report on the State of the Realm, an account of the government's achievements of the past year.[16]

In some countries with presidential or similar systems in which the roles of head of state and head of government are merged, the chief executive's annual speech to the legislative branch is imbued with some of the ceremonial weight of a parliamentary state opening. The most well-known example is the State of the Union Address in the United States. Other examples include the State of the Nation Address in the Philippines, a former American dependency. These speeches differ from a State Opening in at least two respects, however: they do not in fact open the legislative session, and they are delivered by the chief executive on his or her own behalf. In Poland, the President of Poland delivers his speech to Sejm and Senat at the First Sitting of these Houses which is similar to Speech from the Throne. It is rather a custom than a law. Most Presidents of Poland delivered the Speech to the Parliament. The exception was in 2007, when President Lech Kaczyński instead of addressing the Sejm he watched the First Sitting of the 6th term Sejm from the Presidential box in the Press gallery.

References

- 1 2 House of Commons briefing note: The Whip's Office Doc ref. SN/PC/02829. Last updated 10th October 2008

- ↑ Over this robe is worn the collar and George of the Order of the Garter; the George used is a larger than usual gold representation of St. George slaying a dragon and heavily set with diamonds made for George III.

- ↑ The peers also wear their Parliament Robes, also made of crimson velvet and miniver (although the miniver is now often replaced with the much cheaper white rabbit fur). These robes are closed over the right shoulder with bands of gold lace and miniver—four for a duke; three and a half for a marquess; three for an earl or countess; two and a half for a viscount or viscountess and two for a baron or baroness.

- ↑

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Black Rod". Encyclopædia Britannica. 4 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Black Rod". Encyclopædia Britannica. 4 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. - ↑ John Joseph Bagley, A. S. Lewis (1977). "Lancashire at War: Cavaliers and Roundheads, 1642-51 : a Series of Talks Broadcast from BBC Radio Blackburn". p. 15. Dalesman

- 1 2 3 "Democracy Live: Black Rod". BBC. Retrieved 6 August 2008

- ↑ http://www.theguardian.com/politics/2015/may/27/dennis-skinner-queens-speech-quip-fighting-scots-nats

- ↑ "1998: Queen's speech to end peers". BBC News. 31 May 2007.

- ↑ "1998: Queen's speech spells end for peers". BBC News. 24 November 1998.

- ↑ Cobb, H.S., 'The Staging of Ceremonies of State in the House of Lords' in The Houses of Parliament: History, Art, Architecture London: Merrell 2000.

- ↑ Wriothesley Garter Book, Sir Thomas Wriothesley, 1523.

- ↑ Cannadine, D., 'The Palace of Westminster as Palace of Varieties' in The Houses of Parliament: History, Art, Architecture London: Merrell 2000

- ↑ "The State Opening of Parliament - A Perspective from the Archives", www.parliament.uk. Retrieved 2015-09-21

- ↑ State Opening of Parliament (1958) (YouTube). British Pathé. 1958. Retrieved 30 April 2016.

- ↑ "State Opening loses some pomp". BBC News. 24 November 1998. Retrieved 18 May 2016.

- ↑ http://www.royalcourt.no/artikkel.html?tid=30059

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to State Opening of Parliament. |

- Videos of every State Opening since 1988 at C-SPAN

- House of Lords FAQ: State Opening at UK Parliament website

- Parliamentary occasions: State Opening at UK Parliament website

- Cost of the 2006 State Opening at Hansard

- Photos of the 2015 ceremony at Flickr

- Newsreel of the 1960 ceremony at YouTube

.svg.png)