St. Leonard, Quebec

| Saint-Léonard | ||

|---|---|---|

| Borough of Montreal | ||

|

Saint-Léonard church on Jarry Street. | ||

| ||

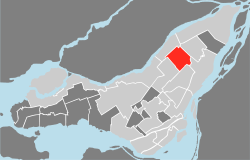

St. Leonard's location in Montreal | ||

| Coordinates: 45°35′09″N 73°35′46″W / 45.58583°N 73.59611°W | ||

| Country |

| |

| Province |

| |

| City | Montreal | |

| Region | Montréal | |

| Merge into Montreal | January 1, 2002 | |

| Electoral Districts Federal |

Saint-Léonard—Saint-Michel | |

| Provincial | Jeanne-Mance–Viger | |

| Government[1][2][3] | ||

| • Type | Borough | |

| • Mayor | Michel Bissonnet (EDC) | |

| • Federal MP(s) | Nicola Di Iorio (LPC) | |

| • Quebec MNA(s) | Filomena Rotiroti (PLQ) | |

| Area[4] | ||

| • Land | 13.51 km2 (5.22 sq mi) | |

| Population (2011)[4][5] | ||

| • Total | 75,707 | |

| • Density | 5,603.8/km2 (14,514/sq mi) | |

| • Change (2006-11) |

| |

| • Dwellings(2006) | 31,105 | |

| Time zone | Eastern (EST) (UTC−5) | |

| • Summer (DST) | EDT (UTC−4) | |

| Area code(s) | Area code 514/438 | |

| Access Routes[6] |

| |

| Website | www.ville.montreal.qc.ca/st-leonard | |

Saint-Léonard (English St. Leonard) is a borough (arrondissement) of Montreal, Quebec, Canada. Formerly a separate city,[7] it was amalgamated into the city of Montreal in 2002. The former city was originally called St-Léonard de Port Maurice after Leonard of Port Maurice.

History

The parish of Saint-Léonard-de-Port-Maurice was founded in April 1886 and eventually became the City of Saint-Léonard-de-Port-Maurice on March 5, 1915.

Italian-Canadian presence

The borough has one of the highest concentrations of Italian-Canadians in the city, along with Riviere-des-Prairies (RDP).[8] As such, it has surpassed Montreal's rapidly gentrifying Little Italy as the centre for Italian culture in the city, with numerous cultural institutions and commercial enterprises serving the city's second-most populous cultural community.[8] By necessity, many services are available in Italian, English and French (the Leonardo da Vinci Centre, for instance, offers cultural activities and events in the three languages). The borough is characterized by its spacious, wide-set semi-detached brick duplexes (and triplexes, four-plexes, and five-plexes — an architectural style unique to Montreal), backyard vegetable gardens, Italian bars (cafés), and pastry shops serving Italian-Canadian staples such as cannoli, sfogliatelle, lobster tails, and zeppole.[9] At some times of year, it is possible to observe seasonal Italian traditions like the making of wine, cheese, sausage, and tomato sauce in quantity. These activities bring extended families and neighbours together and often spill out into front driveways.

St. Leonard Conflict

Italian immigrants have historically established themselves in predominantly Francophone areas of Montreal (Little Italy and Saint-Leonard), and although linguistically Italian is closer to French, Italian-Montrealers have mostly favoured English as a language of education. In 1967, in the midst of Quebec’s Quiet Revolution, the Italian community inadvertently became the primary actor in the linguistic debate coined the “Saint-Leonard Conflict.”[10]

The Saint-Leonard Conflict mainly resulted from the structure of the education system in Montreal prior to the 1960s. Beginning in the mid 1800s, the city’s school systems were divided along religious lines resulting in two independently acting school boards: the Commission des écoles catholiques de Montreal (CÉCM) and the Protestant School Board of Greater Montreal. In order to protect French- Canadian tradition, Franco-Catholic schools systematically refused admission to immigrants’ children. This resulted in the creation of a separate anglophone Catholic division within the CÉCM, accommodating Irish Catholics and eventually also attracting Italian Catholics. In addition, the Protestant system consequently became for decades the dumping ground for immigrants of non-Catholic religious background. This seemed an ideal situation for the French-Canadian elite as long as birth rates remained high in the Francophone population — a situation that prevailed since the post-1760 Conquest phenomenon known as the “revenge of the cradle.” Yet, the Quiet Revolution was also synonymous with the increasing use of birth control pills and changing social habits among the French-Canadian population. This quickly resulted in new demographic challenges that needed to be addressed more than ever to avoid the French language eventually fading away. By the late 1950s, administrators at the CÉCM already began to observe a dramatic increase in Quebec’s English speaking population while birth rates were stagnating among the French-Canadian population.[10]

In the context of the great influx of immigrants to Quebec, and more importantly to Montreal, in the years following World War II, changes seemed imperative in the Government’s policies in order to prevent the 30,000 annual immigrants from increasing the ranks of the English population. The second wave of Italian immigration in Canada between 1951 and 1971, alone, brought 91,821 Italians to Quebec. By 1960, Italians accounted for 15 per cent of newcomers in the province. Often ill-informed of the existence of a French-speaking majority in Quebec before they left for Canada, they perceived English as the language of work and a gateway to North America’s economy; further compelling them to seek education in that language and integrate into the English minority. “In Italy you were taught that Canada is Canada; there was no mention of Quebec’s specific status,” remembers Pietro Lucca, an Italian- Montrealer who experienced the conflict first-hand.

Between 1961 and 1971, the ever-growing Italian population increasingly came to call Saint-Leonard, a Montreal suburb, home. The Saint-Leonard Conflict began in 1967 when an act to remove bilingual schools, the great majority of which were attended by Italian community members, from the municipality was proposed in order to compel primary school children in Saint-Leonard to attend unilingual French schools. The motive behind the Commissioners’ decision was discovering that more than 85 per cent of students graduating from the bilingual program were continuing their secondary education in the Anglophone system.

Italian parents were furious and, in February 1968, founded the Saint-Leonard English Catholic Association of Parents, led by Nick Ciamarra, Frank Vatrano and Mario Barone, to resist the decision. The French community responded to the outburst by creating an organization to counter the Italian movement, the Mouvement pour l’intégration scolaire (MIS), led by French-Canadian lawyer Raymond Lemieux, whose purpose was to ensure that immigrants integrated into the Francophone school system. The clashes between both groups pressured provincial politicians to address the explosive issue of language policy. The fight took place on many fronts: within the government, in court, in the media and even in the streets.[10]

Consequently, the Saint-Leonard Conflict prompted a debate on language legislation for the entire province of Quebec, opposing the importance of individual rights to the importance of collective rights. On one end, supporters of freedom of choice argued that the parents had the right to freely choose their language of instruction, and on the other end, supporters of French unilingualism wanted to impose French schooling on everyone except the English minority of British descent. In addition to being caught in a conflict that was not theirs, Italian-Montrealers felt discriminated against because they believed they were being treated differently than their British counterparts. All the while, the Parents’ Association’s spokesman, Robert Beale, continually tried to convey the hopes and stance of the Italian community stating, “We were not anti-anyone or anti-anything. We were simply demanding the right to have our children educated in the language of our choice, and not have this choice taken away from us.” [10]

After Premier Johnson’s death, Jean-Jacques Bertrand of the Union Nationale campaigned with a promise to directly address the Saint-Leonard crisis by proposing a bill that would protect parents’ freedom of choice in the language of education for their children. When he was elected Premier, Bertrand fulfilled that promise and proposed Bill 85 in the National Assembly on 9 December 1968. While the bill granted freedom of choice, it also sought to secure the position of the majority by requiring all students to have a working knowledge of the French language.[11] Still rather vague, support for the bill was meager. The Minister of Education, Jean-Guy Cardinal, who had nationalist tendencies, did not wholly support the project. MIS leader Raymond Lemieux claimed that the bill legitimized minorities robbing the Francophone population of their language. The Parents’ Association considered the bill too equivocal to give it their support. As such, the bill never made it to a second reading. Bills 63 and 22 followed Bill 85 in 1969 and 1974, respectively. By 1977, Bill 101 was passed in the National Assembly.[12]

Despite what has become an endless debate in the minds of most Quebec citizens, the linguistic struggles of the 1960s and 1970s has paradoxically helped Montreal Italians maintain their cultural heritage unlike any other Italian immigrant community elsewhere in the world. Divided between English and French, Italians depended on their native language to continue communicating with other Italians and members of their family. While children attended school in English, their parents communicated more easily in French; making Italian the communal language bridging the generations. As such, the Italian language survived the first generation of immigrants to Montreal, was actively used by the second generation, and has even lasted into the third, making Montreal’s Italians one of the city’s and the world’s most trilingual communities.[10]

Today, the community newspaper, Progrès Saint-Léonard, is offered exclusively in French.

Demographics

| Historical populations | ||

|---|---|---|

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

| 1966 | 25,328 | — |

| 1971 | 52,035 | +105.4% |

| 1976 | 78,452 | +50.8% |

| 1981 | 79,429 | +1.2% |

| 1986 | 75,947 | −4.4% |

| 1991 | 73,120 | −3.7% |

| 1996 | 71,327 | −2.5% |

| 2001 | 69,604 | −2.4% |

| 2006 | 71,730 | +3.1% |

| 2011 | 75,707 | +5.5% |

| [13] | ||

| Language | Population | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| French | 31,210 | 43.64% |

| English | 17,180 | 24.02% |

| English and French | 1,360 | 1.90% |

| Other languages | 21,755 | 30.42% |

| Ethnic Origin | Population | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| Italian | 27,590 | 39.69% |

| Canadian | 18,915 | 27.21% |

| French | 9,290 | 13.36% |

| Haitian | 3,815 | 5.5% |

| Lebanese | 2,005 | 2.88% |

| Irish | 1,360 | 1.96% |

| Spanish | 1,190 | 1.71% |

| Algerian | 1,155 | 1.66% |

| Arab | 1,155 | 1.66% |

| Portuguese | 1,070 | 1.54% |

Located in the east end of the island of Montreal, Saint-Leonard was traditionally francophone. However, recent census information indicates that the city is now largely composed of numerous generations of 20th-century Italian immigrants.

Linguistic trend

| Language | 1996 | 2001 | 2006 |

|---|---|---|---|

| French | 28,140 | 25,935 | 23,440 |

| English | 4,890 | 4,905 | 6,265 |

| English and French | 870 | 520 | 335 |

| Other languages | 37,425 | 38,155 | 41,480 |

| Population | 71,325 | 69,604 | 71,730 |

Sports and recreation

Aquatics

The Saint-Léonard Aquatic Complex (French: Complexe aquatique de Saint-Léonard) was built in 2006 and is home to three swimming pools: one recreational basin, one 25 meter deep pool and one acclimation basin that includes a turbo bath spa. There are also two saunas, one for women and one for men.

Skate parks

Skaters can skate safely in any one of the two skate parks located in the city of Saint Leonard. Admission to these parks is free, and they are open to the public May through October.

Cycling paths

Saint Leonard has 10 km of bike paths around the city, that connect various parks, pools and city structures.

Hockey

Saint Leonard has two hockey arenas, Aréna Martin Brodeur, located on 5300 boulevard Robert, and Aréna Roberto Luongo, located on 7755 Rue Colbert. These arenas host local games, and usually provide food, locker rooms, showers and public free-skating.

Saint Leonard also has many outdoor hockey rinks in the winter. There are seven rinks set up before winter, and then they are iced when the temperature is appropriate. There was a delay of rink making in 2007 when the weather was warmer than usual.

Soccer

Soccer is a very popular sport for the youth in Saint Leonard. Nearly every public park in has a soccer field open to the public.

Figure skating

Both Saint Leonard arenas are used by the figure skating community. Many Olympic and World Champions have trained here in different disciplines like singles, pairs, dance and synchronized skating.

Other activities

The city has a domed football stadium, Stade Hébert, which is home to the Saint-Léonard Cougars.

There are bocce courts located at almost every public park.

Saint Leonard contains underground caves, located at Pie XII Park.

| Park | Basketball | Soccer | Bocce | Sledding | Fountain | Playground | Ice rink | Pavilion | Tennis | Swimming pool | Skate Park | Baseball | Shuffleboard | Pétanque | Cave | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coubertin Park | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |||||||

| Pie XII Park | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |||

| Ladauversiere Park | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||||||

| Wilfrid Bastien Park | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |||||

| Delorme Park | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |||||||

| Ferland Park | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||||||

| Garibaldi Park | ||||||||||||||||

| Pirandello Park |

Education

Schools

The Borough of Saint-Leonard is served by two school boards. The French schools are part of the Commission scolaire Pointe-de-l'Ile while the English schools are part of the English Montreal School Board.

The Francophone high school is École secondaire Antoine de St-Exupery.[14]

Francophone primary schools:[15]

- Alphonse-Pesant

- Gabrielle-Roy

- La Dauversière

- Pie XII

- Victor-Lavigne

- Wilfrid-Bastien

Anglophone secondary schools:

- Laurier Macdonald High School[16]

- John Paul I Junior High School[17]

Anglophone primary schools:

Public libraries

The borough the Saint-Léonard Library of the Montreal Public Libraries Network.[21]

Mayors

Includes mayors of the former city (1886–2001) and current borough (2002- ) of Saint-Leonard:

- Louis Sicard (1886–1901)

- Gustave Pépin (1901–1903)

- Léon Léonard (1903–1905)

- Jean-Baptiste Jodoin (1905–1906)

- Joseph Léonard (1906–1907)

- Louis D Roy (1907–1910)

- Wilfrid Bastien (1910–1929)

- Pascal Gagnon (1929–1935)

- Philias Gagnon (1935–1939)

- Alphonse D Pesant (1939–1957)

- Antonio Dagenais (1957–1962)

- Paul Émile Petit (1962–1967)

- Leo Ouellet (1967–1974)

- Jean Di Zazzo (1974–1978)

- Michel Bissonnet (1978–1981)

- Antonio Di Ciocco (1981–1984)

- Raymond Renaud (1984–1990)

- Frank Zampino (1990–2008)

- Michel Bissonnet (2009- )

See also

- Boroughs of Montreal

- Districts of Montreal

- Municipal reorganization in Quebec

- Little Italy, Montreal

- Italian-Canadian

References

- ↑ Ministère des Affaires Municipales et Régions: Saint-Léonard

- ↑ Parliament of Canada Federal Riding History: SAINT-LÉONARD--SAINT-MICHEL (Quebec)

- ↑ Chief Electoral Officer of Québec - 40th General Election Riding Results: JEANNE-MANCE-VIGER

- 1 2 3 4 2006 Statistics Canada Community Profile: Saint-Léonard, Quebec

- ↑ "Population totale en 2006 et en 2011 - Variation — Densité" (PDF). Canada 2011 Census (in French). Ville de Montréal. 2012. Retrieved 5 June 2012.

- ↑ Official Transport Quebec Road Map

- ↑ Canadian Politics, Riding by Riding Tony L. Hill - 2002 "The former city of Saint-Léonard was once a key centre for produce growing on Montreal Island, but it's now a middle-class suburb whose burgeoning industry ..."

- 1 2 Panoram Italia - Fun Facts about Montreal Italians!

- ↑ Panoram Italia - Spotlight on Montreal’s East End Italians

- 1 2 3 4 5 http://www.panoramitalia.com/en/arts-culture/history/saint-leonard-conflict-language-legislation-quebec/2325/

- ↑ William Tetley, Language and Education Rights in Quebec and Canada (A Legislative History and Personal Political Diary) (Quebec: Law and Contemporary Problems, 1983), 190.

- ↑ Donat J. Taddeo and Ray Taras, Le debat linguistique au Quebec: la communaute italienne et la langue d'enseignement (Montreal: Presses de l'Universite de Montreal, 1987), 39.

- ↑ "Profil sociodéographique: Arrondissement de Saint-Léonard" (PDF) (in French). Ville de Montréal. 2013. Retrieved 28 October 2013.

- ↑ "Secondaire." Commission scolaire de la Pointe-de-l'Île. Retrieved on December 8, 2014.

- ↑ "Primaire." Commission scolaire de la Pointe-de-l'Île. Retrieved on December 8, 2014.

- ↑ http://www.emsb.qc.ca/en/schools_en/pages/highschool.asp?id=57

- ↑ http://www.emsb.qc.ca/johnpauli/contact.html

- ↑ http://www.danteschool.ca/

- ↑ http://www.emsb.qc.ca/pierredecoubertin/about.html

- ↑ http://www.emsb.qc.ca/honoremercier/

- ↑ "Les bibliothèques par arrondissement." Montreal Public Libraries Network. Retrieved on December 7, 2014.

External links

- Borough website (French)

- Leonardo Da Vinci Center

- City of Montreal. Borrough of St. Leonard (French)

|

|

| ||

| |

|

| ||

| ||||

| | ||||

| |

|

Coordinates: 45°35′09″N 73°35′46″W / 45.585848°N 73.596066°W