St. John's Church, Kolkata

| St. John's Church, Kolkata | |

|---|---|

|

St. John's Church, Kolkata | |

| History | |

| Former name(s) | St. John's Cathedral, Calcutta |

| Architecture | |

| Heritage designation | Protected Monument ASI |

| Architect(s) | James Agg |

| Years built | 1787 |

| Specifications | |

| Length | 180m |

| Width | 120m |

St. John’s Church, originally a cathedral, was among the first public buildings erected by the East India Company after Kolkata became the effective capital of British India.[1] Located at the North – Western corner of Raj Bhavan construction of the St. John’s Church started in 1784, with Rs 30,000 raised through a public lottery,[2] and was completed in 1787. St. John’s Church is the third oldest church in Calcutta (Kolkata) only next to the Armenian and the Old Mission Church.[3] St. John’s Church served as the Anglican Cathedral of Calcutta (Kolkata) till 1847 when it was transferred to St. Paul’s Cathedral. St. John's Church was modeled according to the St Martin-in-the-Fields of London.[4]

History & Architecture

The land for the St. John’s Church was donated by the Maharaja Nabo Kishen Bahadur the founder of the Shovabazar RajFamily.The foundation stone was laid by Warren Hastings, the Governor General of India on 6 April 1784. Two marble plaques at the entrance of the St. John's Church mark the two historic events.

Built by architect James Agg the St John’s church is built with a combination of brick and stone and was commonly known as the “Pathure Girja”[3] (Stone Church). Stone was a rare material in the late 18th century Kolkata. The stones came from the medieval ruins of Gour, and were shipped down the Hooghly River. The minutes book in the church office tell in detail the story of how the ruins of Gaur were robbed to build St John’s church.[4]

The church is a large square structure in the Neoclassical architectural style. A stone spire 174 ft tall is its most distinctive feature. The spire holds a giant clock, which is wound every day.[2]

Interior

Tall columns frame the church building on all sides and the entrance is through a stately portico. The floor is a rare hue of blue-grey marble, brought from Gaur. Large windows allow the sunlight to filter through the coloured glass.

The main altar is of a simple design. Behind the altar is a semi-circular dome and the floor is of dark blue, almost black, stone. To the left of the altar hangs a painting of The Last Supper by the British artist of German origin, Johann Zoffany. On the right is a beautiful stained glass window.

The walls of the church contain memorial tablets, statues and plaques, mostly of British army officers and civil servants.

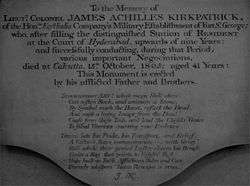

Memorial of James Achilles Kirkpatrick

James Achilles Kirkpatrick, popularly known as the White Mughal was the central character of William Dalrymple best selling work of history White Mughals died in Calcutta on 15 October 1805 at the age of 41. He was buried at the North Park Street Cemetery, but neither his grave nor the cemetery exists today.

James Achilles Kirkpatrick's father James Kirkpatrick, popularly known as the Handsome Colonel, along with his brothers erected a memorial in memory of James Achilles Kirkpatrick on the southern wall of the St. John’s Church. The overblown and oddly inappropriate epitaph, erected still stands to this day.[5]

Memorial of James Pattle

The memorial of James Pattle, the great-great-grandfather of William Dalrymple is also located on the south walls of St. John's Church.

According to Dalrample “Seven generations of my family were born in Calcutta, there are three Dalrymples sitting inside St John’s graveyard. And a great-great-grandfather’s plaque is on the St John’s Church wall, James Pattle.”

“James Pattle was known as the greatest liar in India. A man supposed to be so wicked that the Devil wouldn’t let him leave India after he died. Pattle left instructions that when he died, his body should be shipped back to Britain. So, after his demise (in 1845) they pickled the body in rum, as was the way of transporting bodies back then. The coffin was placed in the cabin of Pattle’s wife and the ship set sail from Garden Reach. In the middle of the night, the corpse broke through the coffin and sat up. The wife had a heart attack and died.”

“Now both bodies had to be preserved in rum. But the casks reeked of alcohol and the sailors bored holes through the sides of the coffins and drank the rum… and, of course, got drunk and the ship hit a sandbank and the whole thing exploded, cremating Pattle and his wife in the middle of the Hooghly! That’s why you see a plaque on the wall and not a grave in the graveyard of my great-great-grandfather.[2]”

Johann Zoffany's Last Supper

On the walls of the St. John’s Church hangs a Leonardo da Vinci style Last Supper. Painted by Johann Zoffany, the painting is not an exact replica of Leonardo’s master piece. Zoffany rather gave an Indian touch to the historic Biblical event.

The top left hand corner of the painting shows a sword, which represents a common peon’s tulwar. Water ewer standing near the table is a copy of Hidustani spittoon and next to it lies a water filled beesty bag (a goat skin bag used for storing water).

The most unusual feature of Zoffany’s Last Supper lies in the selection of model used by Zoffany to represent Jesus and his twelve disciples. Jesus was portrayed Greek priest, Father Parthenio. Judas was portrayed as the auctioneer William Tulloh.[6] While John is represented by W.C.Blacquiere the police magistrate of Calcutta during the 1780s. The effeminate police officer was a master in adopting female disguises. The John of Joffany’s Last Supper ("Disciple whom Jesus loved", after which this church is named) has like Leonardo's painting in Milan, a feminine look. We are reminded of the theme in Dan Brown’s best selling novel The Da Vinci Code.

Zoffany’s Last Supper has been restored as the result of a cooperation between INTACH Art Conservation Centre, Kolkata and the Goethe Institut, Kolkata who sponsored Renate Kant, a German painting conservator based in Singapore to supervise the restoration and train the restorers of the INTACH centre. This photo shows the conserved photo after it was put on display on 3 July 2010.[7]

Compound

The St John's Church was constructed on an old graveyard, so the compound houses a number of tombs and memorials, but only a few dates back to the date of construction of the church. The compound also serves as a parking lot for the nearby offices.

Job Charnock’s Mausoleum

On August 24, 1690 an ambitious trader, Job Charnock, of the British East India Company landed in the village of Sutanuti (present day North Calcutta) never to return. Although Charnock died two years later, but he combined the three villages of Sutanuti, Govindopur & Kolikata to form the city of Calcutta.

The octagonal Moorish style tomb was erected by Charnock’s son in law Charles Ayer. Built of stones brought all the way from Pallavaram near Chennai, which later came out to be known as Charnockite.[8]

The grave also contains the body of Charnock’s wife and several other people, including the famous surgeon William Hamilton

The Epitaph of Charnok’s grave is in latin. The English translation is: "In the hands of God Almighty, Job Charnock, English knight and recently the most worthy agent of the English in this Kingdom of Bengal, left his mortal remains under this marble so that he might sleep in the hope of a blessed resurrection at the coming of Christ the Judge. After he had journeyed onto foreign soil he returned after a little while to his eternal home on the 10th day of January 1692. By his side lies Mary, first-born daughter of Job, and dearest wife of Charles Eyre, the English prefect in these parts. She died on 19 February AD 1696–7.[9]"

Black Hole of Calcutta Monument

For some, the Black Hole of Calcutta event is a controversial part of Indian history; for others it was an atrocity that befell its victims. According to one British survivor (John Holwell), during the siege of Calcutta Siraj - ud – Daulah took 146 prisoners and confined them in a room measuring 14 feet by 8 feet and locked them up overnight. Only 23 survived: the remaining 123 perished of suffocation and heat stroke.

John Holwell later became the Governor of Bengal and went on to build a memorial at the site of the Black Hole (present day GPO). However, some historians have objected to Holwell’s account, claiming that the British escaped through a secret tunnel to the banks of the Hooghly, from where they were carried to Madras by an awaiting ship. One such historian, R. C. Majumdar, claims without evidence to support his assertion that the "Holwell story is completely baseless and can not be considered reliable historical information." In this regard, it should be noted that while it is possible that Holwell exaggerated the number of persons who were confined and died, his account was an eye-witness version of the events that befell the hapless victims and therefore represents direct evidence of the atrocity itself.

The story of the Black Hole Monument is no less interesting. Holwell erected a monument at the site of the Black Hole tragedy but it disappeared in 1822 to be rebuilt by Curzon in 1901 at the SouthWest corner of the Writers' Building. During the height of the Indian independence movement in 1940, the British removed the monument to its present location at the compound of St. John’s Church.

Second Rohilla War Memorial

First and Second Rohilla War (1772 – 74) was fought between the Rohillas and the Nawab of Oudh, with the British backing the later. Rohillas are a branch of the Pashtun tribe of the Pakistan and Afghanistan border. Some of the Rohillas settled in the Oudah region and soon a conflict began between the Rohillas and the Nawab of Oudh, Shuja – ud – Daula. This resulted in Rohilla War.

The British backed the Nawab of Oudh and in January 1774 the Rohilla chief Hafez Ruhmet was killed resulting in the defeat of the Rohillas. A treaty in October 1774 brought the dispute to a close. With their power somewhat restricted the Rohillas continued to live in their territory of Rohilkhand, which still exists in the state of Uttar Pradesh.

The Rohilla Memorial at the St. John’s Church compound consists of a circular dome supported by 12 pillars. The memorial contains a plaque with the names of several British Military Officers, killed in the Rohilla War.

Charlotte Canning, Countess Canning Memorial

Charlotte Canning (1817–1861) was the wife of Charles Canning the Governor General and Viceroy of India. She died of malaria and was buried in Barrackpore (Barrackpurthe)a memorial was also constructed in the St. John’s Church graveyard.

Lady Canning's name has been immortalised by the famous sweet maker Bhim Nag, who specially designed the sweet Pantua in her honor and named it Ladykeni.

Lady Canning’s elaborately decorated memorial lies on the Northern corridor of the St. John’s Church.

Francis (Begum) Johnson’s grave

Located at the far end of the St. John’s Church complex and next to Job Chranok’s tomb lies the circular temple-like tomb of Francis Johnson (1725–1812). The grave stone inside the grave is no less interesting than the grave itself.

Francis Johnson (popularly known as Begum Johnson), the grand old lady of Calcutta, lived up to an age of 89 and married four times. The epitaph makes an interesting reading, as its describes the entire life of Fransis Johnson, with details of her four husbands and their respective children.

See also

References

- ↑ "Kolkata: Heritage Tour: Religious Buildings: St. John's Church". kolkatainformation.com. 2003. Retrieved 24 January 2012.

- 1 2 3 Chakraborty, Lahiri,, Samhita (January 3, 2010). "Wicked man on the wall". The Telegraph. Retrieved January 25, 2012.

- 1 2 Roy, Nishitranjan,Swasato Kolkata Ingrej Amaler Sthapathya, (Bengali), pp. 24, 1st edition, 1988, Prtikhan Press Pvt. Ltd.

- 1 2 Das, Soumitra (June 22, 2008). "Gour to St. John's". The Telegraph. Retrieved January 24, 2012.

- ↑ William, Dalrymple (2002). "White Mughals". Penguin Books. p. 401.

- ↑ William, Dalrymple (2002). "White Mughals". Penguin Books. p. 268 note.

- ↑ Das, Soumitra (July 1, 2010). "Look, Last Supper restored". The Telegraph. Retrieved January 25, 2012.

- ↑ Roy, Nishitranjan,Swasato Kolkata Ingrej Amaler Sthapathya, (Bengali), pp. 18, 1st edition, 1988, Prtikhan Press Pvt. Ltd.

- ↑ Das, Soumitra,Jay Walkers Guide to Calcutta,Jan 2007, Eminence Designs.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to St. John's Church, Kolkata. |

Coordinates: 22°34′12″N 88°20′47″E / 22.569911°N 88.346297°E