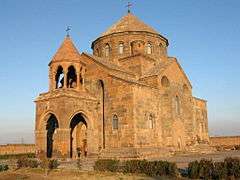

Saint Hripsime Church

| Saint Hripsime Church | |

|---|---|

|

View of the church, 2009 | |

| Basic information | |

| Location | Vagharshapat, Armavir Province, Armenia |

| Geographic coordinates | 40°10′01″N 44°18′35″E / 40.166992°N 44.309675°ECoordinates: 40°10′01″N 44°18′35″E / 40.166992°N 44.309675°E |

| Affiliation | Armenian Apostolic Church |

| Rite | Armenian |

| Status | Active |

| Architectural description | |

| Architectural type | Tetraconch[1] |

| Architectural style | Armenian |

| Founder | Komitas Aghtsetsi |

| Completed | 618 (current building)[1][2][3] |

| Specifications | |

| Length | 22.8 metres (75 ft)[4] |

| Width | 17.7 metres (58 ft)[4] |

| Official name: Cathedral and Churches of Echmiatsin and the Archaeological Site of Zvartnots | |

| Type | Cultural |

| Criteria | ii, iii |

| Designated | 2000 (24th session) |

| Reference no. | 1011 |

| Region | Western Asia |

Saint Hripsime Church (Armenian: Սուրբ Հռիփսիմե եկեղեցի, Surb Hřip’simē yekeghetsi; sometimes Hripsimeh)[5][6] is a seventh century Armenian Apostolic church in the city of Vagharshapat (Etchmiadzin), Armenia. It is one of the oldest surviving churches in the country. The church was erected by Catholicos Komitas to replace the original mausoleum built by Catholicos Sahak the Great in 395 AD that contained the remains of the martyred Saint Hripsime to whom the church is dedicated. The current structure was completed in 618 AD. It is known for its fine Armenian-style architecture of the classical period, which has influenced many other Armenian churches since. It was listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site along with other nearby churches, including Etchmiadzin Cathedral, Armenia's mother church, in 2000.

History

Background

Hripsime, along with the abbess Gayane and thirty-eight unnamed nuns, are traditionally considered the first Christian martyrs in Armenia's history. They were persecuted, tortured, and eventually killed by king Tiridates III of Armenia. According to the chronicler Agathangelos, after conversion to Christianity in 301, Tiridates and Gregory the Illuminator built a martyrium[3] dedicated to Hripsime at the location of her martyrdom, which was half buried underground.[2][7] In 395 Patriarch Sahak the Parthian (Isaac of Armenia) rebuilt or built a new martyrium, which had been destroyed by the Persians.[2][7]

During excavations in 1958 stones with Hellenistic ornaments were found under the supporting column, which proved that a Hellenistic pagan temple once stood in its place.[2][8] Excavations around the church have uncovered remains of several tortured women buried in early Christian manner, which "seem to support the story of Agathangelos."[9]

Current building

The current building was erected during the reign of Catholicos Komitas (615–628),[10] according to an account of contemporary chronicler Sebeos and two inscriptions, one on the west facade and the other on the east apse. It replaced the earlier mausoleum of Hripsime.[1][10] The church is suggested by scholars to have been completed in 618.[1][2][7][8][11] The dome was probably restored in the 10th[2] or 11th centuries, although some scholars have argued that it is the original 7th century construction.[1]

.jpg)

Modern period

The church was dilapidated and abandoned[7] by the early 17th century.[2][8] It was renovated by Catholicos Philipos in 1653, under whose commission an open narthex (gavit) was erected in front of the western entrance.[2][8] In 1776 the church was fortified with a brick wall and pyramids on the corners by Catholicos Simeon I of Yerevan.[2][7] In 1880 the eastern and southern walls were built of smoothly hewn stone.[8] A bell tower was built on the narthex (gavit) in 1880.[2][12] The church underwent considerable renovation in 1898.[2][8] Its foundations were strengthened and the roof and dome were repaired in 1936.[1] In 1958 plaster from was removed from the interior walls and the interior floor was lowered.[1][2] The bell tower was renovated in 1987.[7]

Architecture

St. Hripsime Church is a "tetraconch with angular niches [with] inner octagon with cylindrical niches in corners."[1] It has been described as a "gem of Armenian architecture"[14] and "one of the most complex compositions in Armenian architecture."[12] St. Hripsime Church, along with Saint Gayane Church, stands as a "model of the austere beauty of early Armenian ecclesiastical architecture."[10] The church, with its "domed tetraconch enclosed in a rectangle and its monumental exterior, is considered one of the great achievements of medieval Armenian architecture."[15] German art historian Wilhelm Lübke wrote that the church is built on "a most complicated variation of the cruciform ground-plan."[16]

Influence

The church is not the earliest example of this architectural form, however, the form is widely known in architectural history as the "Hripsime-type" since the church is the best-known example of the form. Notable churches with similar plans include the Surb Hovhannes (Saint John) Church of Avan (6th century), Surb Gevorg (Saint George) Church of Garnahovit (6th century), Church of the Holy Cross at Soradir (6th century), Targmanchats monastery of Aygeshat (7th century),[2] Holy Cross Cathedral of Aghtamar (10th century),[2][12][17][18] and Surb Astvatsatsin (Holy Mother of God) Church at Varagavank (11th century).[19] The architectural form is also found in neighboring Georgia,[3] where examples include the Ateni Sioni Church (7th century), Jvari monastery (7th century), and Martvili Monastery (10th century).[2]

Gallery

- Artistic and historic depictions

View of Etchmiadzin by Mikhail Ivanov, 1783. St Hripsime Church can be seen on the left

View of Etchmiadzin by Mikhail Ivanov, 1783. St Hripsime Church can be seen on the left Kurds and Persians attacking Vagharshapat by Grigory Gagarin, 1847

Kurds and Persians attacking Vagharshapat by Grigory Gagarin, 1847 From H. F. B. Lynch's 1901 book on Armenia[20]

From H. F. B. Lynch's 1901 book on Armenia[20] from a 1901 Russian book

from a 1901 Russian book a 1911 photo reproduced in Strzygowski's 1918 book[4]

a 1911 photo reproduced in Strzygowski's 1918 book[4].jpg) by Yeghishe Tadevosyan, 1913

by Yeghishe Tadevosyan, 1913 by Fridtjof Nansen, 1925

by Fridtjof Nansen, 1925 A relief of St. Hripsime Church on the headquarters of the Eastern Diocese of the Armenian Church of America next to the St. Vartan Cathedral in Manhattan, New York

A relief of St. Hripsime Church on the headquarters of the Eastern Diocese of the Armenian Church of America next to the St. Vartan Cathedral in Manhattan, New York Model of the church displayed at the American Museum of Natural History in New York

Model of the church displayed at the American Museum of Natural History in New York

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "Saint Hrp'sime". armenianstudies.csufresno.edu. California State University, Fresno.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 Eremian, A. (1980). "Հռիփսիմեի տաճար [Hripsime temple]". Soviet Armenian Encyclopedia Volume 6 (in Armenian). Yerevan: Armenian Encyclopedia Publishing. pp. 596–597.

- 1 2 3 Hunt, Lucy-Anne (2008). "Eastern Christian Iconographic and Architectural Traditions: Oriental Orthodox". In Parry, Ken. The Blackwell Companion to Eastern Christianity. John Wiley & Sons. p. 394.

...was influential in Armenia and early imitations of it are found in Georgia...

- 1 2 3 Strzygowski 1918, p. 92.

- ↑ Dalton, Ormonde Maddock (1925). East Christian art: a survey of the monuments. Hacker Art Books. p. 33.

...in Armenia, such as the cathedral of Edgmiatsin, the church at Bagaran, and the Hripsimeh church at Vagharshapat...

- ↑ Svajian, Stephen G. (1977). A Trip Through Historic Armenia. GreenHill Pub. p. 85.

According to Lynch, the interior of the chapel has the features of St. Hripsimeh Church in Etchmiadzin.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Էջմիածնի Սուրբ Հռիփսիմե եկեղեցի". encyclopedia.am (in Armenian). Armenian Encyclopedia.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Saint Hripsime Church". hushardzan.am. Service for the Protection of Historical Environment and Cultural Museum Reservations, Ministry of Culture of the Republic of Armenia. 1 February 2012.

- ↑ Hacikyan, Agop Jack; Basmajian, Gabriel; Franchuk, Edward S.; Ouzounian, Nourhan (2000). The Heritage of Armenian Literature: From the Oral Tradition to the Golden Age. Detroit: Wayne State University Press. p. 121. ISBN 9780814328156.

- 1 2 3 Adalian, Rouben Paul (2010). Historical Dictionary of Armenia. Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow Press. p. 298. ISBN 978-0-8108-7450-3.

- ↑ Kiesling, Brady (2000). Rediscovering Armenia: An Archaeological/Touristic Gazetteer and Map Set for the Historical Monuments of Armenia (PDF). Yerevan/Washington DC: Embassy of the United States of America to Armenia. p. 34.

- 1 2 3 "Սուրբ Հռիփսիմե վանք". ejmiatsin.am (in Armenian). Municipality of Ejmiatsin. 2 March 2012.

- ↑ Strzygowski 1918, p. 94.

- ↑ Ellen and Peter Boer (2013). Grand Tourist. Xlibris Corporation. p. 222. ISBN 9781483603049.

- ↑ Foss, Clive (2003). "The Persians in the Roman Near East (602–630 AD)". Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society. 13 (2): 155.

- ↑ Lübke, Wilhelm (1881). Cook, Clarence, ed. Outlines of the History of Art Volume I. New York: Dodd, Mead, and Company. p. 441.

- ↑ Wharton, Alyson (2015). The Architects of Ottoman Constantinople: The Balyan Family and the History of Ottoman Architecture. I.B. Tauris. p. 62. ISBN 9781780768526.

...Cathedral of the Holy Cross (915–21) on Akhtamar in Lake Van, which follows the Surp Hripsime model...

- ↑ Cheterian, Vicken (2015). Open Wounds: Armenians, Turks and a Century of Genocide. Oxford University Press. p. 239. ISBN 9780190263508.

- ↑ Hasratyan, Murad (2002). "Վարագավանք [Varagavank]". Yerevan State University Institute for Armenian Studies (in Armenian). "Christian Armenia" Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on 8 October 2014.

...Վարագավանքի գլխ.՝ Ս. Աստվածածին եկեղեցին (XI դ.), որն ունի «հռիփսիմեատիպ» կառույցների հորինվածքը...

- ↑ Lynch 1901, pp. 268-269.

Bibliography

- Academic articles

- Published books

- Lynch, H. F. B. (1901). Armenia, travels and studies. Volume I: The Russian Provinces. London: Longmans, Green, and Co.

- Strzygowski, Josef (1918). Die Baukunst der Armenier und Europa [The Architecture of the Armenians and of Europe] Volume I (in German). Vienna: Kunstverlag Anton Schroll & Co. pp. 92–94.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to St. Hripsime church in Vagharshapat. |

.jpg)