Spuyten Duyvil Creek

Coordinates: 40°52′30″N 73°55′5″W / 40.87500°N 73.91806°W

Spuyten Duyvil Creek /ˈspaɪtən ˈdaɪvəl/ is short tidal estuary connecting the Hudson River to the Harlem River Ship Canal and then on to the Harlem River in New York City. The confluence of the three separate the island of Manhattan from the Bronx and the rest of the mainland. Once a distinct, turbulent waterway between the Hudson and Harlem rivers, the creek has been subsumed by the modern ship canal.

The Bronx neighborhood of Spuyten Duyvil lies to the north of the creek, and, as a result of the construction of the ship canal and the creek's subsequent in-filling, so does Manhattan's Marble Hill neighborhood.

Etymology

"Spuyten Duyvil" may be literally translated as "Spouting Devil" or Spuitende Duivel in Dutch; a reference to the strong and wild tidal currents found at that location. It may also be translated as "Spewing Devil" or "Spinning Devil", or more loosely as "Devil's Whirlpool" or "Devil's Spate." Spui is a Dutch word involving outlets for water.[1] Historian Reginald Pelham Bolton, however, argues that the phrase means "sprouting meadow", referring to a fresh-water spring.[2]

History

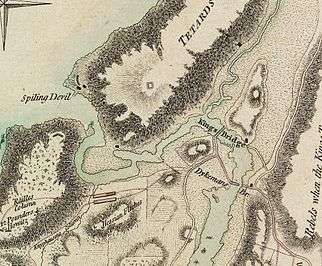

Spuyten Duyvil Creek runs northeast into the Hudson. When the Dutch settlers arrived they found its tidal waters turbulent and difficult to handle. Though its tides raced[3] was no navigable watercourse joining it with the headwaters of the Harlem River,[4] which flowed in an "S"-shaped course southwest and then north[5] into the East River. Steep cliffs along the Spuyten Duyvil's mouth at the Hudson prevented any bridge there, but upstream it narrowed into a rocky drainage. There a Dutch nobleman who had sworn allegiance to the Crown upon the British takeover of New Netherlands, Frederick Philipse, built the King's Bridge in 1693.

Originally a merchant in New Amsterdam, Philipse had purchased vast landholdings in what was then Westchester County. Granted the title Lord of Philipse Manor, he established a plantation and provisioning depot for his shipping business upriver on the Hudson in present-day Sleepy Hollow. His toll bridge provided access and opened his land to settlement. Later, it carried the Boston Post Road. The span was sited near to and ran roughly parallel to what is now West 230th Street in the Bronx, with its south end in an area then and until 1914 physically part of Manhattan.

Harlem River Ship Canal

Over time the channels of the Spuyten Duyvil and Harlem River were joined and widened, but transit was still difficult and confined to small craft. With the advent of the Erie Canal and large steamships in the second half of the 19th century, a broad shipping canal was proposed to allow them thru-transit by bypassing the tight turn up and around Marble Hill. The Harlem Canal Company was founded in 1826, but did not make any progress towards building a canal. The U.S. Congress broke the logjam in 1873 by approrpiating money for a survey of the relevant area, following which New York state bought the necessary land and gave it to the federal government. Construction of the Harlem River Ship Canal – officially the United States Ship Canal[6] – finally started in January 1888 on a canal that would be 400 feet (120 m) in width and have a depth of 15 feet (4.6 m) to 18 feet (5.5 m). It would be cut directly through the rock of Dyckman's Meadow, making a straight course to the Hudson River. The cut at Marble Hill was made in 1895, and the second cut there in 1938.[7]

The effect of channeling through what had been West 222nd and 223rd streets was to physically isolate Marble Hill on the Bronx side of the new strait. In 1914 the original creekbed was filled in with rock from the excavation for the foundation of Grand Central Station;[8] and the temporary island, comprising present-day Marble Hill, became physically attached to the Bronx, though it remained politically part of the borough of Manhattan, as it is today.

Another channel was dug in 1937-38[9] to the west of the 1895 realignment straightening the Spuyten Duyvil towards the Hudson. It pared off a protruding tip of the Bronx, which was absorbed into Manhattan's Inwood Hill Park, home now to its Nature Center.[10]

Today, Spuyten Duyvil Creek, the Harlem River Ship Canal, and the Harlem River form a continuous channel, referred to collectively as the Harlem River. Broadway Bridge, a combination road and rail lift span, continues to link Marble Hill with Manhattan.[11] There is little evidence that the building of the Ship Canal enhanced commerce in the city.[8]

Bridges

Three bridges cross the Spuyten Duyvil Creek; from west to east, they are:

- The Spuyten Duyvil Bridge, a railroad swing bridge that carries Amtrak's Empire Corridor line between Penn Station and Albany

- The Henry Hudson Bridge, a steel arch toll bridge that carries the Henry Hudson Parkway (New York State Route 9A)

- Broadway Bridge, a vertical lift bridge carrying vehicular and pedestrian traffic on one level, and the subway on the upper level.

See also

References

Notes

- ↑ Sixteenth Annual Report, 1911, of the American Secneic and Historic Preservation Society to the Legislature of the State of New York , p. 106. American Scenic and Historic Preservation Society, 1911. Accessed November 4, 2015. "Another reason is that there are phonetic elements in the name as first written which suggest other meanings quite appropriate to the locality. There is a Dutch word 'spui' of frequent use in Holland, meaning a sluice way or canal. The Spui at The Hague, part of which is redeemed and used as a street, is a famous thoroughfare."

- ↑ Sypher, Frank J. "Dispute Springs Eternal Over 'Spuyten Duyvil'" (letter to the editor) The New York Times (November 14, 1993)

- ↑ "Although the river is very narrow, it is deep, and the tide runs rapidly under the bridge, alternately both ways, as the tide ebbs and flows." (Diary, July 5, 1787) in Cutler, William Parker; Cutler, Julia Perkis; Dawes, Ephraim Cutler; and Force, Peter. Life, Journals and Correspondence of Rev. Manasseh Cutler, LL. D., p. 227. Cincinnati, Ohio: Rovert Clark & Company, 1888.

- ↑ "Here we cross the River upon a tall bridge made of wood, the Inn and this bridge belong to the same person...the river is no(t) at all Navigable As there’s abundance of rocks between this bridge and North (Hudson) River." in Birket, James. Some Cursory Remarks Made by James Birket in His Voyage to North America 1750-1751 New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press, 1916.

- ↑ Eldredge & Horenstein (2014), pp.102-103

- ↑ Eldredge & Horenstein (2014), pp.104-105

- ↑ Eldredge & Horenstein (2014), pp.103-105

- 1 2 Eldredge & Horenstein (2014), p.105

- ↑ Randomsky, Rosalie. "If You're Thinking of Living In Spuyten Duyvil; Sunsets Over the Palisades, and Legends" The New York Times (May 29, 1994) Quote: "Most of the peninsula was destroyed by 1937 to widen the Harlem River Ship Canal. The remaining wedge, between a railroad cut and water, became known as the Columbia Rock...."

- ↑ Renner, James (September 2005). "Johnson Ironworks Factory". Washington Heights & Inwood Online. Retrieved 2010-01-15.

- ↑ Betts, John H. The Minerals of New York City originally published in Rocks & Minerals magazine, Volume 84, No . 3 pages 204-252 (2009).

Bibliography

- Eldredge, Niles & Horenstein, Sidney (2014), Concrete Jungle: New York City and Our Last Best Hope for a Sustainable Future, Berkeley, California: University of California Press, ISBN 978-0-520-27015-2

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Spuyten Duyvil Creek. |

- History of Spuyten Duyvil Creek from Washington Heights & Inwood Online

- Tracing Spuyten Duyvil today