Spin–lattice relaxation

Spin–lattice relaxation is the mechanism by which the component of the magnetization vector along the direction of the static magnetic field reaches thermodynamic equilibrium with its surroundings (the "lattice") in nuclear magnetic resonance and magnetic resonance imaging. It is characterized by the spin–lattice relaxation time, a time constant known as T1. It is named in contrast to T2, the spin-spin relaxation time.

Nuclear physics

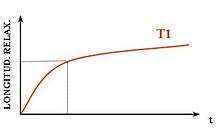

T1 characterizes the rate at which the longitudinal Mz component of the magnetization vector recovers exponentially towards its thermodynamic equilibrium, according to equation:

Or, for the specific case that

It is thus the time it takes for the longitudinal magnetization to recover approximately 63% [1-(1/e)] of its initial value after being flipped into the magnetic transverse plane by a 90° radiofrequency pulse.

Nuclei are contained within a molecular structure, and are in constant vibrational and rotational motion, creating a complex magnetic field. The magnetic field caused by thermal motion of nuclei within the lattice is called the lattice field. The lattice field of a nucleus in a lower energy state can interact with nuclei in a higher energy state, causing the energy of the higher energy state to distribute itself between the two nuclei. Therefore, the energy gained by nuclei from the RF pulse is dissipated as increased vibration and rotation within the lattice, which can slightly increase the temperature of the sample. The name spin-lattice relaxation refers to the process in which the spins give the energy they obtained from the RF pulse back to the surrounding lattice, thereby restoring their equilibrium state. The same process occurs after the spin energy has been altered by a change of the surrounding static magnetic field (e.g. prepolarization by or insertion into high magnetic field) or if the nonequilibrium state has been achieved by other means (e.g. hyperpolarization by optical pumping).

The relaxation time, T1 (the average lifetime of nuclei in the higher energy state) is dependent on the gyromagnetic ratio of the nucleus and the mobility of the lattice. As mobility increases, the vibrational and rotational frequencies increase, making it more likely for a component of the lattice field to be able to stimulate the transition from high to low energy states. However, at extremely high mobilities, the probability decreases as the vibrational and rotational frequencies no longer correspond to the energy gap between states.

Different tissues have different T1 values. For example, fluids have long T1s (1500-2000 ms), and water based tissues are in the 400-1200 ms range, while fat based tissues are in the shorter 100-150 ms range. The presence of strongly magnetic ions or particles (e.g. ferromagnetic, paramagnetic) also strongly alter T1 values and are widely used as MRI contrast agents.

T1 weighted images

Magnetic resonance imaging uses the resonance of the protons to generate images. Protons are excited by a radiofrequency pulse of an appropriate frequency (Larmor frequency) and then emit energy in the form of radiofrequency (RF) signal as they return to their original state. The magnetisation of the proton ensemble goes back to its equilibrium value with an exponential curve characterized by a parameter T1 (see Relaxation (NMR)).

T1 weighted images can be obtained by setting short TR ( < 750 ms ) and TE ( < 40 ms ) values in conventional spin echo sequences, while in Gradient Echo Sequences they can be obtained by using flip angles of larger than 50o while setting TE values to less than 15 ms.

T1 is significantly different between grey matter and white matter and is used when undertaking brain scans. A strong T1 contrast is present between fluid and more solid anatomical structures, making T1 contrast suitable for morphological assessment of the normal or pathological anatomy, e. g. for musculoskeletal applications.

See also

References

- McRobbie D., et al. MRI, From picture to proton. 2003

- Hashemi Ray, et al. MRI, The Basics 2ED. 2004.