Spider Bridge at Falls of Schuylkill

| Spider Bridge at Falls of Schuylkill | |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 40°00′09″N 75°06′49″W / 40.0024°N 75.1135°WCoordinates: 40°00′09″N 75°06′49″W / 40.0024°N 75.1135°W |

| Crosses | Schuylkill River |

| Locale | Philadelphia, Pennsylvania |

| Characteristics | |

| Design | Footbridge |

| Material | Iron wire |

| Total length | 407 feet (124 m) |

| Width | 1 foot 6 inches (0.46 m) |

| Number of spans | 1 |

| History | |

| Constructed by | Josiah White & Erskine Hazard |

| Opened | 1816 |

| Closed | 1817? |

Spider Bridge at Falls of Schuylkill Location in Pennsylvania | |

Spider Bridge at Falls of Schuylkill was an iron-wire footbridge erected in 1816 over the Schuylkill River, north of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Though a modest and temporary structure, it is thought to have been the first wire-cable suspension bridge in world history.[1]

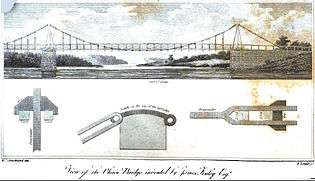

Chain bridge

The Chain Bridge at Falls of Schuylkill, an iron-chain suspension bridge designed by James Finley, was built at Falls of Schuylkill in 1808.[3] It was among the earliest suspension bridges erected in the United States. To supply materials for its construction, ironmakers Josiah White and Erskine Hazard built a rolling mill along the river near its eastern abutment.[4]

Although Finley patented his Falls of Schuylkill bridge and publicized it widely, it was not a success: "Part of the superstructure broke down in September, 1810, while a drove of cattle was crossing it, and in January, 1816, the bridge fell down, occasioned by the great weight of snow which remained on it, and a decayed piece of timber."[5]

Wire footbridge

The collapse of the Chain Bridge was a great inconvenience for the village of Falls of Schuylkill, with the nearest bridge being "The Colossus", five miles downstream. Josiah White seems to have used the Chain Bridge as the model for his wire footbridge, substituting iron wire for Finley's iron chains.

"White & Hazard had two mills on the western side of the river,—one a saw-mill, the other a mill for making white lead. The wire-mills were on the east side of the river. There were two buildings at one time. On one of the occasions of the breaking down of the Falls [Chain] bridge, White & Hazard erected a curious temporary bridge across the river by suspending wires from the top windows of their mill to large trees on the western side, which wires hung in a curve, and from which were suspended other wires supporting a floor of boards eighteen inches [0.45 m] wide. The length of the floor of this bridge was four hundred feet [121.9 m], without intermediate support. The entire cost was one hundred and twenty-five dollars. They charged a toll of one cent per passenger, and when, from that revenue, the cost of the structure was realized they made the structure free."[6]

"Notice was given that only eight persons would be allowed on it at a time, but 'A Visitor,' writing to the [Pennsylvania] Gazette, said that he 'saw thirty people on it at a time, including rude boys running backward and forward.'"[7]

There is no exact record of how long the Spider Bridge remained open, although it was probably less than a year.[8] A wooden covered bridge, built upon the Chain Bridge's abutments, was completed in 1818.[9]

Watson

A British Army officer visiting Philadelphia in 1816, Captain Joshua Rowley Watson, saw potential for military use in what he called the "Spider Bridge". He recorded its length as 407 feet (124 m), drew an elevation and plan of it, and described it in his diary:

"[June] 15th. There is at this spot a manufactory of Wire, the proprietor, a very ingenious man, has constructed a Spider bridge across the Schuylkill to enable his workmen to go to & from their work—his name is White, a quaker.

The principle on which this very curious work is constructed, I look on as original; The horizontal line or footway is suspended on the segment of a circle made by two iron wires, carried across the river, and fastened at each end to the Manufactory on one side, and to a Tree on the other, at the height of about 50 feet from [above] the water; to the main wires are fastened, at equal distances, perpendicular wires to which are affixed pieces of wood, on which the planks of the footway rest; and by another wire on each side, which keep the perpendiculars steady, there is a very secure railway [guardrail] made to assist the passengers in crossing the river.

The length of the footway is 407 feet the width of it 18 inches—Mr White informed me, he had placed 45 men on it at the same time, & that he thinks 50 men might cross at a time, if they walked steady. Such a flying bridge as this might easily be made out of two five inch hausers, with the necessary perpendicular ropes, and carried across a river in a very short time, so as to enable a body of troops to secure an opposite shore, and the whole of the apparatus might be so contrived that two wagons would carry it."

"July 1st. I crossed the Wire Bridge, before discribed [sic]; the vibration is great, and to a person not used to such sort of motion, the walking on it is attended with difficulty. We met Mr White the inventor and proprietor. It communicates with his Wire & Nail Manufactory."[10]

Watson's plan and elevation document the bridge's structure.[11] The two main cables were anchored about 50 feet above the water to the top story of White's manufactory on the east shore and to boughs of a tree on the west. Twenty-four pairs of suspender cables (hangers), about 16 feet apart, dropped from the main cables and attached to the ends of the wooden floor beams. Wooden joists spanned between the floor beams, creating a substructure that was decked with 2-foot planks. A pair of horizontal wires strung from shore to shore tied together the suspender cables and floor beams, and a second pair functioned as guardrails. Six guy-wires anchored the bridge to rocks in the river and on both shores. Another pair of guy-wires anchored the tree to other trees behind it. A guyed mast at mid-river, about twice the height of a man, functioned as the center suspender cable where the main cables dipped to the level of the deck. At each shore the narrow walkway was at ground level; over the river it was suspended about 16 feet above the water.

Cordier

French engineer Joseph Louis Etienne Cordier published a description of the wire footbridge in 1820:

"The bridge of iron wire erected over the Schuylkill near Philadelphia is also worth describing as it is the very first to have been built in this manner. It is attached to one of the window mullions[12] of an iron wire factory on the one bank, and to a great tree on the other. The two curves which carry the bridge are made up of three iron wires which, taken together, have a diameter of 3/8". From time to time, vertical iron wires are hung from these curves. These in turn support the iron wires which carry the deck 16 feet above the water. The planks of the footpath are 2' long, 3" wide and 1" thick. 8 iron wires attached on either side, serve as guide rails.

A bridge of this type can be erected in 15 days in summer, the total cost being less than 300 dollars."[13]

the total weight of the iron wire is 1314 lb that of the woodwork is 3380 lb that of the nails is 8 lb total 4702 lb

Location

Mid-19th-century photographs of Falls of Schuylkill show two- and three-story buildings lining the river's banks. One of these may be White & Hazard's rolling mill, the building to which the Spider Bridge's main cables were anchored.[14]

The exact location of the wire footbridge has not been identified, but it was between the Reading Railroad Bridge (built 1853–56, still in use) and the Falls Bridge, probably about where the Roosevelt Boulevard's Twin Bridges now cross the Schuylkill River.

Falls of Schuylkill, from the western side of the river. The Reading Railroad Bridge (built 1853–56, still in use) is at the approximate location of the Chain Bridge. One of the buildings on the far shore may be White & Hazard's rolling mill. Laurel Hill Cemetery is visible at upper right.

Falls of Schuylkill, from the western side of the river. The Reading Railroad Bridge (built 1853–56, still in use) is at the approximate location of the Chain Bridge. One of the buildings on the far shore may be White & Hazard's rolling mill. Laurel Hill Cemetery is visible at upper right. "View from Laurel Hill Cemetery, Phila." The Spider Bridge was located upstream of the Chain Bridge, somewhere between the Reading Railroad Bridge (center) and the Falls Covered Bridge (upper right).

"View from Laurel Hill Cemetery, Phila." The Spider Bridge was located upstream of the Chain Bridge, somewhere between the Reading Railroad Bridge (center) and the Falls Covered Bridge (upper right). Twin Bridges in 2010, with Reading Railroad Bridge (left) and Falls Bridge (far right).

Twin Bridges in 2010, with Reading Railroad Bridge (left) and Falls Bridge (far right).

See also

References

- ↑ Peterson, Charles E. (March 22, 1986). "The Spider Bridge, A Curious Work at the Falls of Schuylkill, 1816". Canal History and Technology Proceedings. v: 243–59.

- ↑ Strickland's elevation has been misidentified as Finley's Jacob's Creek Bridge (1801), but that bridge had a single span of 70 feet. The Port Folio image shows a 200-foot span bridge. Strickland's elevation also was published with the caption: "Chain Bridge over the Schuylkill at the Falls." Jackson, p. 412.

- ↑ Falls of Schuylkill was outside the city limits until 1854, when Philadelphia County merged into the City of Philadelphia.

- ↑ Jackson, pp. 411–12.

- ↑ Jackson, p. 412.

- ↑ Charles V. Hagner, Early History of Falls of Schuylkill, Manayunk, Schuylkill and Lehigh Navigation Companies, Fairmount Waterworks, Etc. (Philadelphia: Claxton, Remsen & Haffelfinger, 1869), as quoted in J. Thomas Scharf and Thompson Westcott, History of Philadelphia, 1609–1884 (Philadelphia: L.H. Everts & Co., 1884), vol. 1, p. 584.

- ↑ Scharf & Westcott, p. 584.

- ↑ John Bowie, ed., Workshop of the World: A Selective Guide to the Industrial Archeology of Philadelphia (Wallingford, PA: Oliver Evans Press, 1990), pp. 11-25.

- ↑ Jackson, 412.

- ↑ Kathleen A. Foster and Kenneth Finkel, Captain Watson's Travels in America: The Sketchbooks and Diary of Joshua Rowley Watson, 1772–1818 (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1997). pp. 57–59, 29–96, fig. 30.

- ↑ Josiah White's wire bridge over the Schuylkill River, from Google books.

- ↑ This detail is mistranslated or misunderstood. According to Watson's elevation and plan, the main cables were anchored to the stone wall of White & Hazard's manufactory through two windows, not anchored to a mullion dividing a single window.

- ↑ Joseph Louis Etienne Cordier, Histoire de la Navigation Interieure (1820), vol. 2, pp. 182–83, as quoted in Tom F. Peters, Transitions in Engineering: Guillaume Henri Dufour and the Early 19th Century Cable Suspension Bridges, (Boston: Birkouser, 1987), pp. 34–36. ISBN 0-8176-1929-1

- ↑ Fred Perry Powers, "Early Schuylkill Bridges", Philadelphia History, vol. 1, no. 11, (1914), pp. 306–08.

Sources

- "Finley's Chain Bridge," The Portfolio [Magazine], vol. 3, no. 6 (June 1810).

- Joseph Jackson, "Chain Bridge," Encyclopedia of Philadelphia, Volume 2 (Harrisburg: National Historical Association, Inc., 1931).

External links

- 1816 (footbridge) from Bridgemeister.