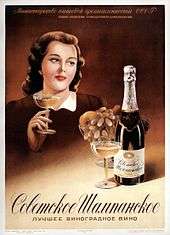

Sovetskoye Shampanskoye

Sovetskoye Shampanskoye (Советское шампанское, 'Soviet Champagne') is a generic brand of sparkling wine produced in the Soviet Union and successor states. It was produced for many years as a state-run initiative. Typically the wine is made from a blend of Aligoté and Chardonnay grapes.

After the Soviet Union dissolved, private corporations in Belarus, Russia, Moldova, and Ukraine purchased the rights to use "Soviet Champagne" as a brand name and began manufacturing once again. "Soviet Champagne" is still being produced today by those private companies, using the original generic title as a brand name.

History

Russian Tsar Pavel I first brought together Crimean vines and French master Champagne-makers but it was a Russian aristocrat, Prince Golitsyn, who established the first economically successful Russian sparkling wine at Abrau-Dyurso. So successful was Golitsyn that in 1900 at the Paris World Fair, Novy Svet champagne defeated all the French entries to claim the internationally coveted 'Grand Prix de Champagne'.[1]

When the Russian revolution swept the Bolsheviks to power in October 1917 the brand name-industry was nearly washed away. But as the Soviet Union developed in the early 1920s, the government asked the Russian wine-makers to devise a recipe for a new 'champagne for the people' that would be cheap, quick to produce and accessible to the working masses. The new brand, named "Sovetskoye Shampanskoye", was created in 1928 by a Sovnarkhoz team. The "father" of the new technology was Anton Frolov-Bagreyev, a former employee of Prince Golitsyn at Abrau-Dyurso.[2] In a dramatic incident during the Russian civil war, Frolov-Bagreyev had nearly been killed for refusing the demand of a proletarian squad to yield all of the factory's wine stock. He only survived because of the help of the factory workers who hid him behind the wine barrels and alerted the Soviet authorities.[1] Frolov-Bagreyev went on to receive a number of state scholarships, academic degrees, and the Stalin Prize for his work in Soviet wine-making.[1] The technology of production was further improved and made more economical in 1953 by Professor Georgy Agabalyanc, who received the Lenin Prize for that achievement.[1] In 1975 Moët & Chandon bought a licence for production of sparkling wine by Soviet method.[3]

Legal status

In Latvia the Supreme Court has ruled that Latvijas Balzams, a local producer of Sovetskoye Shampanskoye, has sole right to use the trademark in Latvia.[4] In other former Soviet republics, the use of the brand is not restricted. Several producers use the name, including wine producers from Italy and Spain.

Under European Union law, as well as treaties accepted by most nations, sparkling wines produced outside the champagne region, even wine produced in other parts of France, do not have the right to use the term "champagne". Hungary (which originally produced Sovetskoye Shampanskoye under Soviet license), by contrast, today produces the beverage under the name Sovetskoye Igristoye, a name that was also used by some Soviet producers.

Other brands are Odessagne, imported from wineries in Odessa built by the French to supply the Russian nobility, and Sparkling 1917, a brut sparkling wine made in Belarus with wine from Moldova, imported into the UK and rebranded for British tastes.

In January 2016 the Ukrainian producer announced the renaming of the brand to Sovetovskoye Shampanskoye to comply with the decommunization law.[5]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 Империя вкуса. "Советское шампанское: рожденное революцией". Retrieved on 04-7-2008

- ↑ Katrina Kollegaeva (24 August 2016). "Crimea's champagne makers hope to recreate the Soviet glory days". The Guardian. Retrieved 19 September 2016.

- ↑ Kommersant

- ↑ Court orders L.I.O.N. & Ko to withdraw Sovetskoje Shampanskoje from the market - The Supreme Court has upheld the claim of Latvijas Balzams to ban sale of Sovetskoje Shampanskoje that is distributed by L.I.O.N.& Ko. (Google cache)

- ↑ Shaun Walker (4 January 2016). "Ukrainians say farewell to 'Soviet champagne' as decommunisation law takes hold". The Guardian. Retrieved 19 September 2016.