Sonnenschein–Mantel–Debreu theorem

| Economics |

|---|

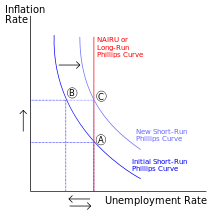

Phillips curve graph, illustrating an economic principle |

|

|

| By application |

|

| Lists |

|

The Sonnenschein–Mantel–Debreu theorem (named after Gérard Debreu, Rolf Mantel, and Hugo F. Sonnenschein) is a result in general equilibrium economics.[1][2][3][4] It states that the excess demand function for an economy is not restricted by the usual rationality restrictions on individual demands in the economy. Thus, microeconomic rationality assumptions have no equivalent macroeconomic implications. The theorem's main implications are that, with many interdependent markets within the economy, there might not exist a unique equilibrium point. Frank Hahn regarded the theorem as the most dangerous critique against the micro-founded mainstream economics.[5]

Statement of the theorem

Formally, the theorem states that the Walrasian aggregate excess-demand function inherits only certain properties of individual excess-demand functions:

- Continuity

- Homogeneity of degree zero,

- Walras' law, and

- boundary condition assuring that, as prices approach zero, demand becomes large.

These inherited properties are not sufficient to guarantee that the aggregate excess-demand function obeys the weak axiom of revealed preference. The consequence of this is that the uniqueness of the equilibrium is not guaranteed : the excess-demand function may have more than one root – more than one price vector at which it is zero (the standard definition of equilibrium in this context).

The range of implications is however not limited to just the absence of uniqueness: "There are problems with establishing general results on uniqueness (Ingrao and Israel 1990,chap. 11; Kehoe 1985, 1991; Mas-Colell 1991), stability (Sonnenschein 1973; Ingrao and Israel 1990, chap. 12; Rizvi 1990, 94–144), comparative statics (Kehoe 1985; Nachbar 2002, 2004), econometric identification (Stoker 1984a, 1984b), microfoundations of macroeconomics (Kirman 1992; Rizvi 1994b), and the foundations of imperfectly competitive general equilibrium (Roberts and Sonnenschein 1977; Grodal 1996). Subfields of economics that relied on well-behaved aggregate excess-demand for much of their theoretical development, such as international economics, were also left in the lurch (Kemp and Shimomura 2002)."[6]

Occasionally the Sonnenschein–Mantel–Debreu theorem is referred to as the “Anything Goes Theorem”.[6]

Explanation

The reason for the result is the presence of wealth effects. A change in a price of a particular good has two consequences. First, the good in question is cheaper or more expensive relative to all other goods, which tends to increase or decrease the demand for that good, respectively – this is called the substitution effect. On the other hand the price change also affects the real wealth of consumers in society, making some richer and some poorer, which depending on their preferences will make some demand more of the good and some less – the wealth effect. The two phenomena can work in opposite or reinforcing directions, which means that more than one set of prices can clear all markets simultaneously.

In mathematical terms, the number of equations is equal to the number of individual excess-demand functions, which in turn equals the number of prices to be solved for. By Walras' law, if all but one of the excess demands is zero then the last one has to be zero as well. This means that there is one redundant equation and we can normalize one of the prices or a combination of all prices (in other words, only relative prices are determined; not the absolute price level). Having done this, the number of equations equals the number of unknowns and we have a determinate system. However, because the equations are non-linear there is no guarantee of a unique solution. Furthermore, even though reasonable assumptions can guarantee that the individual excess-demand functions have a unique root, these assumptions do not guarantee that the aggregate demand does as well.

There are several things to be noted. First, even though there may be multiple equilibria, every equilibrium is still guaranteed, under standard assumptions, to be Pareto efficient. However, the different equilibria are likely to have different distributional implications and may be ranked differently by any given social welfare function. Second, by the Hopf index theorem, in regular economies the number of equilibria will be finite and all of them will be locally unique. This means that comparative statics, or the analysis of how the equilibrium changes when there are shocks to the economy, can still be relevant as long as the shocks are not too large. But this leaves the question of the stability of the equilibrium unanswered as a comparative statics point of view does not allow one to know what happens when one moves from one equilibrium : it has no reason to move to a new one.

Some critics have taken the theorem to mean that General equilibrium analysis cannot be usefully applied to understand real-life economies since it makes imprecise predictions (hence, the “Anything Goes” moniker). Others have countered that there is no a priori reason why one should expect a real-life economy to have a unique equilibrium and hence the possibility of multiple outcomes is in fact a realistic feature of the theory , with the saving grace that it is still possible to analyze local shocks in a 'comparative statics' view point.

Extension to incomplete markets

The extension to incomplete markets was first conjectured by Andreu Mas-Colell in 1986.[7] To do this he remarks that Walras' law and Homogeneity of degree zero can be understood as the fact that the excess demand only depends on the budget set itself. Hence, homogeneity is only saying that excess demand is the same if the budget sets are the same. This formulation extends to incomplete markets. So does Walras law if seen as budget feasibility of excess-demand function. The first incomplete markets Sonnenschein–Mantel–Debreu type of result was obtained by Jean-Marc Bottazzi and Thorsten Hens (1996).[8] Other works expanded the type of assets beyond the popular real assets structures like Chiappori and Ekland (1999).[9] All such results are local.

Finally, Takeshi Momi (2003) extended the approach by Bottazzi and Hens as a global result.[10]

References

- ↑ Sonnenschein, H. (1972). "Market excess-demand functions". Econometrica. 40 (3): 549–563. doi:10.2307/1913184. JSTOR 1913184.

- ↑ Sonnenschein, H. (1973). "Do Walras' identity and continuity characterize the class of community excess-demand functions?". Journal of Economic Theory. 6: 345–354. doi:10.1016/0022-0531(73)90066-5.

- ↑ Mantel, R. (1974). "On the characterization of aggregate excess-demand". Journal of Economic Theory. 7: 348–353. doi:10.1016/0022-0531(74)90100-8.

- ↑ Debreu, G. (1974). "Excess-demand functions". Journal of Mathematical Economics. 1: 15–21. doi:10.1016/0304-4068(74)90032-9.

- ↑ Hahn, Frank (1975). "Revival of Political Economy - The Wrong Issues and the Wrong Argument". The Economic Record. 51 (135): 360–364.

- 1 2 Rizvi, S. Abu Turab (2006). "The Sonnenschein-Mantel-Debreu Results after Thirty Years" (PDF). History of Political Economy. Duke University Press. 38. doi:10.1215/00182702-2005-024.

- ↑ Mas-Colell, A. (1986). "Four lectures on the differentiable approach to general equilibrium". Lecture Note in Mathematics. 1330: 19–49.

- ↑ Bottazzi, J.-M. and T. Hens (1996). "Excess-demand functions and incomplete market". Journal of Economic Theory. 68: 49–63. doi:10.1006/jeth.1996.0003.

- ↑ Chiappori, P.-A. and I. Ekeland (1999). "Aggregation and Market Demand: An Exterior Differential Calculus Viewpoint". Econometrica. 67: 1435–1457. doi:10.1111/1468-0262.00085. JSTOR 2999567.

- ↑ Momi, T. (2003). "Excess-Demand Functions with Incomplete Markets–A Global Result". Journal of Economic Theory. 111: 240–250. doi:10.1016/S0022-0531(03)00061-9.