Solitary Islands Marine Park

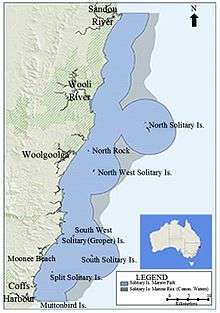

Solitary Islands Marine Park is a marine park in New South Wales State waters, Australia. It adjoins the Solitary Islands Marine Reserve (Commonwealth Waters) and was declared under the Marine Parks Act 1997 (NSW) in January 1998.[2] Prior to this it was declared a marine reserve in 1991.[3] The Park was one of the first declared in NSW and stretches along the northern NSW coast, from Muttonbird Island, Coffs Harbour, to Plover Island near Sandon River, 75 kilometres to the north. It includes coastal estuaries and lakes and extends from the mean high water mark, to three nautical miles out to sea, covering an area of around 72 000 hectares.[4] There are five main islands in the Park, North Solitary Island, North West Solitary Island, South West Solitary Island (Groper Island), South Solitary Island and Split Solitary Island, as well as other significant outcrops such as Muttonbird Island and submerged reefs.

On 15 May 1770, Lieut. James Cook sailed past the Solitary Islands and noted their position in his journal, “Between 2 and 4 we had some small rocky Islands between us and the land the southernmost lies in the Latitude of 30°10' and the northernmost in 29°58' and about 2 Leagues or more from the land.”[5] He named them the "Solitary Isles" on his chart.[6]

Ecology

The Solitary Island Marine Park contains a diverse range of habitats including intertidal and subtidal reefs, soft sediments, beaches, seagrass beds, mangroves, saltmarsh and open waters, which support a large variety of fauna and flora.[3] The northern section of the marine park borders the Yuragir National Park,[3] between Sandon River and Red Rock, which contains several open and closed lakes and lagoons. As well as bordering Moonee Beach Nature Reserve, Garby Nature Reserve at Arrawarra, and Coffs Coast Regional Park, it also incorporates Muttonbird Island Nature Reserve, Split Solitary Island Nature Reserve, South West Solitary Island Nature Reserve, North West Solitary Island Nature Reserve, North Rock Nature Reserve, North Solitary Island Nature Reserve and the South Solitary Island Historic Site which covers 11 hectares and incorporates the lighthouse and keepers cottages built in 1879. Prior to European settlement, none of these islands had been inhabited, burned or subject to grazing animals. A fragile balanced ecology had built up over centuries.[7]

The coastal areas adjoining the Marine Park are high in species richness and endemism [8] and the waters around the Solitary Islands are strongly influenced by the warm East Australian Current.[9] The continental shelf of northern NSW lies at the juncture of tropical and temperate oceanographic regions,[9] and the sea temperature patterns within the Solitary Islands region explains the cross-shelf gradients in biotic patterns. Both tropical and temperate faunas overlap here,[10] and for many species the Marine Park may represent either their northern or southern limits.

Flora

Vegetation types in the Marine Park include freshwater and marine ecosystems as well as, mangroves and saline communities, frontal dune and foreshore communities and exposed high dune sand systems. Millar[11] (1990), records 119 species of Red Algae from the Coffs Harbour Region, including 22 which were new records for Australia, and Dictyothamnion (D. saltatum) constituting a new genus.

Mangroves are found in sheltered estuarine environments in a transitional zone between land and sea, generally in an intertidal area and provide habitat for many fish, birds and invertebrates. Two types of mangroves dominate, grey mangrove (Avicennia marina) and river mangrove (Aegiceras corniculatum).[3]

The vegetation on the islands and headlands in the region are dwarf grassy heath and rocky heath that struggle with shallow soils and salty winds. Threatened plant species found growing on the headlands, include Carpet Star (Zieria prostrata), which is endemic to the Coffs Harbour region,[12] (Plectranthus cremnus)[13] and Austral Toadflax (Thesium austral).[14]

North Solitary Island: Pigface (Carpobrotus glaucescens), Couch grass (Cynodon dactylon), Summer grass (Digitaria sanguinalis), Wandering Jew (Commelina cyanea), Coast Morning Glory (Ipomoea cairica), Yellow-flowered Oxalis (Oxalis corniculata) and Saltbush (Ragodia hastata).[15]

North-West Solitary Island: Pigface, Saltbush, Prickly Couch (Zoisia macrantha), Wandering Jew, Coast Morning Glory are predominant species.[16]

South-West Solitary Island: Pigface, Wandering Jew, Variable groundsel (Senecio Lautus), New Zealand Spinach (Tetragonia tetragonioides), Climbing Saltbush (Rhagodia nutans), Tuckeroo (Cupaniopsis anacardioides), Prickly Couch, Dusky Coral Pea (Kennedia rubicunda), and Shore Spleenwort (Asplenium obtusatum).[17]

South Solitary Island: vegetation consists mainly of grasses including Prickly couch, Whiskey grass (Andropogon virginicus), Durrington grass (Axonopus affinis), Slender mudgrass, (Pseudoraphis paradoxa) and Buffalo grass (Stenotaphrum secundatum).[18]

Birdie (small islet at northern end of South Solitary Island): Wandering Jew, Coast Morning Glory, New Zealand Spinach, Coastal yellow Pea (Vigna marina), Pennywort (Hydrocotyle acutiloba) and Pigweed (Portulaca oleracea).[18]

Split Solitary: Climbing Saltbush, Variable Groundsel, Pigface, Wandering Jew, Coastal Yellow Pea and Sword Bean (Canavalia maritima).[19]

Korfs Islet: Pigface, Prickly couch, Summer grass (Digitaria ciliaris), Ruby saltbush (Enchylaena tomentosa) and Sea purslane (Sesuvium portulacastrum).[20]

Muttonbird Island: Pigface, Tuckeroo, Wandering Jew, Dusky Coral Pea, Prickly couch, Weeping grass (Microlaena stipoides), Lantana (Lantana camara), Flax Lily (Dianella caerulea), Bull Cane (Flagellaria indica),[21] and introduced Spiny burr grass (Cenchrus caliculatus) which have spread.[22]

Fauna

Birds

Seabirds, shorebirds, waders, waterfowl and raptors depend on marine and estuaryine habitats.[23][24] The Solitary Islands are an important breeding area for marine birds such as Osprey (Pandion cristatus),[3] while threatened species such as the Australian Pied Oystercatcher (Haematopus longirostris), Sooty Oystercatcher (H. fuliginosus) and Beach Stone-curlew (Esacus magnirostris) are local shorebirds that breed in the Marine Park.[25] It also periodically hosts three endangered marine birds, Gould’s Petrel (Pterodroma leucoptera), Wandering Albatross (Diomedea exulans) and Southern Giant Petrel (Macronectes giganteus).[26]

Endangered Little Terns (Sternula albifrons) breed on beaches north and south of Coffs Harbour, between October and February, before departing on their annual migration to eastern Asia. A Little Tern Recovery Program is managed by National Parks and Wildlife Service who aim to help the species recover sufficient numbers.[27] Wedge-tailed shearwaters (Puffinus pacificus), called Muttonbirds by early settlers, migrate to the Philippines, but return annually to a major breeding site at Muttonbird Island, on the southern boundary of the Marine Park.[28] There are over 5500 breeding pairs on Muttonbird Island,[21][29] but breeding occurs on some of the other islands as well.[19] Other breeding birds recorded on the islands include Little Penguins (Eudyptula minor), Black-winged Petrel (Pterodroma nigripennis), Silver Gulls (Chroicocephalus novaehollandiae) and Crested Tern (Sterna bergii).[29]

Migratory shorebirds that spend the summers at the Marine Park, like the Bar-tailed Godwit (Limosa lapponica),[30] Eastern Curlew (Numenius madagascariensis)[31] and the Ruddy Turnstone (Arenaria interpres),[32] breed in Siberia, Alaska or the Arctic.[25] Raptors such as the White-breasted Sea-eagle (Haliaeetus leucogaster) [15][20] Brahminy kite (Haliastur indus) and Osprey are often seen hunting for fish in the Marine Park, and waterbirds such as herons and egrets (Egretta spp), as well as sacred kingfishers (Todiramphus sanctus), are regularly seen in the estuaries.

Mammals

Around 30 species of marine mammals have been recorded in the region, including the Short-beaked common dolphin (Delphinus delphis)[33] and bottlenose dolphin (Tursiops truncates) who are residents throughout the year. Of particular interest in the Marine Park and Reserve are those species listed as threatened and subject to national and international conventions. These mammals include humpback whales (Megaptera novaeangliae), who are commonly encountered in the area as they migrate north to their breeding grounds in June and July, and then again between September and November when they return south, Southern right whales (Eubalaena australis) and Blue whales (Balaenoptera musculus).[3]

At the edge of the marine park, the endangered Little Bent-wing Bat, (Miniopterus australis) roost in caves on the Moonee Beach headland.[13]

While there was a lighthouse keeper on South Solitary Island, rabbits (Oryctolagus cuniculus), goats (Capra hircus) and dogs were introduced to the island to the detriment of the vegetation, but these animals have since been removed.[18] Rats (Rattus norvegicus), bandicoots (Isoodon spp.) and foxes (Vulpes vulpes) have been found on Muttonbird Island,[22] which is connected to the mainland by a causeway, however National Parks and Wildlife Service have an eradication program in place to control this.

Fish

858 species of fish are found in the Solitary Islands Marine Park.[3] The area around Pimpernel Rock, at the northern end of the Solitary Islands Marine Reserve (Commonwealth Waters) is favoured by the endangered Grey nurse shark (Carcharias taurus), who has a preference for gutters in reefs and submarine caves.[2] However the most significant habitat for the grey nurse shark in the Marine Park is South Solitary Island, though they do occur throughout the park.[3] The Great white shark (Carcharodon carcharias) is also seen around Pimpernel Rock.[2] There are many species of reef fish in the Park, including snapper (Pagrus auratus), tusk fish (Choerodon venustus), blue morwong (Nemadactylus douglasii) and pearl perch (Glaucosoma scapulare) as well as pelagic species such as kingfish (Seriola lalandi)[3] that are attractive to commercial and recreational fishermen. Commercial fishing fleets operate from Coffs Harbour and Wooli.

The area on the western side of North West Rock (off North Solitary Island) is known as "Fish Soup” and has a very high diversity of fish. Tropical predators like spangled emperor (Lethrinus nebulosus), bigeye trevally (Caranx sexfasciatus), mangrove jack (Lutjanus argentimaculatus), moses perch (Lutjanus russellii) and brown sweetlip (Plectorhinchus gibbosus) occur with mulloway (Argyrosomus japonicus), snapper, red morwong (Cheilodactylus fuscus), silver trevally (Pseudocaranx georgianus), bream (Acanthopagrus spp.) and tarwhine (Rhabdosargus sarba).[3]

Reptiles

Marine turtles are common in the Park, with green turtle (Chelonia mydas), loggerhead turtle (Caretta caretta), hawksbill turtle (Eretmochelys imbricata) and occasional sightings of leatherback turtles. Nesting green turtles and loggerhead turtles have been recorded on several beaches, with some eggs hatching successfully. Only a few species of sea snakes have been recorded in the region, including the Elegant sea snake (Hydrophis elegans) and Yellow-bellied sea snake (Pelamis platurus).[3]

The only reptile recorded on Muttonbird Island since 1969 is Burton’s Snake Lizard (Lialis burtonis) though Eastern Water Dragons (Physignathus lesueurii) were plentiful prior to 1930.[22]

Invertebrates

At depths greater than 25 metres the sea bottom is dominated by sponges and invertebrates. More than 700 species of molluscs (snails and shellfish) and coral are found in the Marine Park. Invertebrate species found include blue-bottles, sea-squirts, sea-whips and black coral (Antipatharia), as well as oysters (Saccostrea and Crassostrea species) and crustaceans such as crabs (Scylla serrata, Portunus pelagicus and Ranina ranina), prawns (all species in family Penaeidae) and crayfish (Jasus verreauxi, Scyllarus spp. and Panulirus spp.).[26] Commercial prawn trawling is allowed in the general use area of the Park and crab and lobster trapping in both the general use and habitat protected areas.[34]

Coral

The Solitary Islands region contains the southernmost extensive coral communities in coastal eastern Australia. The East Australian Current transports the coral larvae from the warm tropical waters, and with 90 reported species, there are approximately quarter of the species recorded on the Great Barrier Reef.[9][35]

Environmental threats and issues

Even though the Marine Park is a protected zone, commercial fishing and recreational activities such as fishing, crabbing, boating and scuba diving are allowed in some zones of the park.[1] Environmental threats to the Solitary Islands Marine Park may include pollution, introduced predators, oil spills, humans, dredging, sewage outfalls, shipping, marine debris, and tourism. Introduced pests such as the Pacific Oyster (Crassostrea gigas) and the Crown-of-thorns starfish (Acanthaster planci) are occacionally recorded in the area.[3]

Introduced domestic animals on South Solitary Island during the days of lighthouse keepers, destroyed the natural vegetation, and eroded topsoil,[36] which in turn caused the nesting Wedgetail shearwaters’ burrows to collapse.

An accidental fire on South West Solitary Island, caused by fishermen, destroyed much vegetation, killing nesting birds and their eggs.[36]

Due to the rocky nature of the area, a number of ships were wrecked on the northern NSW coast. This led to the construction of a series of lighthouses, with the South Solitary Island lighthouse being completed in 1870.[36]

During the 1960s and 70s many of the beaches were affected by sand mining.

Litter in marine environments is a threat to seabirds, causing entanglement or ingestion of debris, often leading to death.[36]

Management

The Solitary Island Marine Park is managed by the NSW Maritime Parks Authority and is split into 4 management zones: Sanctuary zones (12%) which provide the highest level of environmental protection, with all fishing activities prohibited. Habitat protection zones (54%) allow for many recreational activities such as fishing but provides a high level of environmental protection. General use zone (34%) allows commercial fishing as well as a wider range of activities, and lastly the Special Purpose zones (0.1% of park) cover sites of cultural significance to the Aboriginal community, research sites and oyster leases.[37] South Solitary Island with its lighthouse and cottages is a historic site. Visiting the island is allowed for two weekends of the year, in July, by helicopter.

Public Moorings: A number of public moorings have been installed in the Park, and are located within the sanctuary zone around Northwest Rock, North Solitary Island, North West Solitary Island, South West Solitary Island (Groper Is.), Split Solitary Island, South Solitary Island and Surgeons Reef.[1]

References

- 1 2 3 NSW Marine Parks Authority. (2011). Solitary Island Marine Park & Solitary Islands Marine Reserve (Commonwealth Waters) - zoning summary and user guide. Retrieved 20/05/2015, from http://www.environment.gov.au/system/files/resources/8f451416-4b49-4eac-8287-4153281f2ae5/files/solitary-user-guide-map.pdf.

- 1 2 3 Commonwealth of Australia. (2001). Solitary Islands Marine Reserve (Commonwealth Waters) Management Plan. Environment Australia, Canberra.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 NSW Marine Parks Authority. (2008). Natural values of the Solitary Islands Marine Park.

- ↑ NSW Marine Parks Authority. (2013). Solitary Islands Marine Park - Southern Sanctuary Zone.

- ↑ Cook, J. (1771). Journal of H.M.S. Endeavour, 1768-1771 [manuscript]. Retrieved 20/05/2015, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.ms-ms1-s236r

- ↑ Cook, J. (1770). A Chart of New South Wales, or the East Coast of New Holland. Discover'd and Explored By Lieutenant J. Cook, Commander of his Majesty's Bark Endeavour, in the Year MDCCLXX. from http://southseas.nla.gov.au/journals/maps/zoom_au.html

- ↑ Yeates, N. T. M. (1990). Coffs Harbour. Vol 1: Pre- 1880 to 1945. Coffs Harbour: Bananacoast Printers.

- ↑ Chrisp, M. D., Laffan, S., Linder, H. P., & Munro, A. (2001). Endemism in Australian flora. Journal of Biogeography, 28, 183-198. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2699.2001.00524.x

- 1 2 3 Zann, L. P. (2000). The Eastern Australian Region: a Dynamic Tropical/Temperate Biotone. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 41, 188-203. doi:10.1016/S0025-326X(00)00110-7

- ↑ Malcolm, H. A., Davies, P. L., Jordan, A., & Smith, S. D. A. (2011). Variation in sea temperature and the East Australian Current in the Solitary Islands region between 2001-2008. Deep-Sea Research Part II: Topical Studies in Oceanography, 28(5), 616-627. doi:10.1016/j.dsr2.2010.09.030

- ↑ Millar, A. J. K. (1990). Marine red algae of the Coffs Harbour region, northern New South Wales. Australian Systematic Biology, 3, 293-593. doi:10.1071/SB9900293

- ↑ NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service. (1998). Zieria prostrata Recovery Plan. Sydney: NPWS.

- 1 2 NPWS North Coast Region. (2003). Moonee Beach Nature Reserve: NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service.

- ↑ NSW Office of Environment and Heritage. (2013). Austral Toadflax - profile. Retrieved 20/05/2015, from http://www.environment.nsw.gov.au/threatenedspeciesapp/profile.aspx?id=10802

- 1 2 Lane, S. G. (1974a). Seabird Islands No 6, North Solitary Island, New South Wales. The Australian Bird Bander, 12, 14-15.

- ↑ Morris, A. K. (1975). Seabird Islands No12, North-West Solitary Island, New South Wales. The Australian Bird Bander, 13, 58-59.

- ↑ Lane, S. G. (1975a). Seabird Islands No 10, South-West Solitary Island, New South Wales. The Australian Bird Bander, 13, 14-15.

- 1 2 3 Lane, S. G. (1975b). Seabird Islands No 14, South Solitary Island, New South Wales. The Australian Bird Bander, 13, 80-82.

- 1 2 Lane, S. G. (1974b). Seabird Islands No 9. Split Solitary Island, New South Wales. The Australian Bird Bander, 12, 79.

- 1 2 Lane, S. G. (1976). Seabird Islands No 33, Korffs Islet, New South Wales. The Australian Bird Bander, 14, 92.

- 1 2 Floyd, R. B., & Swanson, N. M. (1983). Wedge-tailed Shearwaters on Muttonbird Island: an estimate of the breeding success and the breeding population. Emu, 82, 244-250. doi:10.1071/MU9820244s

- 1 2 3 Swanson, N. M. (1976). Seabird Islands No 32, Mutton Bird Island, New South Wales. The Australian Bird Bander, 14, 88-89.

- ↑ Higgins, P. J. (Ed.). (1999). Handbook of Australian, New Zealand and Antarctic Birds. Volume 4: Parrots to Dollarbird. Melbourne: Oxford University Press.

- ↑ Higgins, P. J., & Davies, S. J. J. F. (Eds.). (1996). Handbook of Australian, New Zealand and Antarctic Birds. Volume 3: Snipe to Pigeons. (Eds.). (1993). Handbook of Australian, New Zealand and Antarctic Birds. Volume 2: Raptors to Lapwings. Melbourne: Oxford University Press.

- 1 2 NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service. (nd). Shorebirds of the Coffs Coast: NSW Office of Environment & Heritage.

- 1 2 Rule, M. J., Jordan, A., & McIlgorm, A. (2007). The marine environment of northern New South Wales: a review of current knowledge and existing datasets. Coffs Harbour: National Marine Science Centre.

- ↑ NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service. (2008). Little Terns of the Coffs Coast- Bongil Bongil National Park and Hearnes Lake: Dept of Environment & Climate Change NSW.

- ↑ NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service. (2004). Muttonbird Island - Nature Reserve: Dept of Environment and Conservation.

- 1 2 Lane, S. G. (1979). Summary of the breeding seabirds on New South Wales coastal islands. Corella, 3, 7-10.

- ↑ Gill, R. E., Douglas, D. C., Handel, C. M., Tibbitts, T. L., Hufford, G., & Piersma, T. (2014). Hemispheric-scale wind selection facilitates bar-tailed godwit circum-migration of the Pacific. Animal Behaviour, 90, 117-130. doi:10.1016/j.anbehav.2014.01.020

- ↑ Finn, P. G., Catterall, C. P., & Driscoll, P. V. (2007). Determinants of preferred intertidal feeding habitat for Eastern Curlew: A study at two spatial scales. Austral Ecology, 32(2), 131-144. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-9993.2006.01658.x

- ↑ Weishu, H., & Purchase, D. (1987). Migration of Banded Waders between China and Australia. Colonial Waterbirds,10, 106-110. doi: 10.2307/1521239

- ↑ Möller, L., Valdez, F. P., Allen, S., Bilgmann, K., Corrigan, S., & Beheregaray, L. B. (2011). Fine-scale genetic structure in short-beaked common dolphins (Delphinus delphis) along the East Australian Current. Marine Biology, 158, 113-126. doi:10.1007/s00227-010-1546-x

- ↑ NSW Marine Parks Authority. (2011b). Solitary Island Marine Park & Solitary Islands Marine Reserve (Commonwealth Waters) - zoning summary and user guide.

- ↑ Harriott, V. J., Smith, S. D. A., & Harrison, P. L. (1994). Patterns of coral community structure of subtropical reefs in the Solitary Islands Marine Reserve, Eastern Australia. Marine Ecology Progress Series, 109, 67-76. doi: 10.3354/meps109067

- 1 2 3 4 NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service. (2012). Solitary Islands group of reserves: Draft Management Plan. NSW Office of Environment and Heritage.

- ↑ NSW Marine Parks Authority. (nd). Solitary Islands Marine Park: Consultation & Management. Retrieved 20/05/2015, from http://www.mpa.nsw.gov.au/simp-consulatation.html

Coordinates: 19°55′24″S 119°54′54″E / 19.92333°S 119.91500°E