Swedish Social Democratic Party

Sweden's Social Democratic Workers' Party Sveriges socialdemokratiska arbetareparti | |

|---|---|

| |

| Abbreviation | S, SAP |

| Leader | Stefan Löfven |

| Secretary-General | Lena Rådström Baastad |

| Parliamentary group leader | Tomas Eneroth |

| Founded | 23 April 1889 |

| Headquarters | Sveavägen 68, Stockholm |

| Student wing | Social Democratic Students of Sweden |

| Youth wing | Swedish Social Democratic Youth League |

| Women's wing | Social Democratic Women in Sweden |

| Religious wing | Religious Social Democrats of Sweden |

| Membership (2014) | 100,900[1] |

| Ideology |

Social democracy[2][3] Democratic socialism[3] |

| Political position | Centre-left |

| European affiliation | Party of European Socialists |

| International affiliation |

Progressive Alliance, Socialist International (observer) |

| European Parliament group | Progressive Alliance of Socialists and Democrats |

| Nordic affiliation | SAMAK |

| Colours | Red |

| Riksdag |

113 / 349 |

| European Parliament |

5 / 20 |

| County councils[4] |

572 / 1,597 |

| Municipal councils[5] |

4,364 / 12,780 |

| Website | |

|

www | |

The Swedish Social Democratic Party, (Swedish: Sveriges socialdemokratiska arbetareparti, SAP; literally, "Social Democratic Workers' Party of Sweden"),[6] contesting elections as the Arbetarepartiet–Socialdemokraterna ('The Workers' Party – The Social Democrats'), usually referred to just as the 'Social Democrats' (Socialdemokraterna); is the oldest and largest political party in Sweden. The current party leader since 2012 is Stefan Löfven; he has also been Prime Minister of Sweden since 2014.

History

Founded in 1889, a schism occurred in 1917 when the left socialists split from the Social Democrats to form the Swedish Social Democratic Left Party (later the Communist Party of Sweden and now the Left Party). The symbol of the SAP is traditionally a red rose, which is believed to have been Fredrik Ström's idea. The words of honour, as recorded by the 2001 party programme, are "freedom, equality, and solidarity."

The Social Democratic Party's position has a theoretical base within Marxist revisionism. Its party programme interchangeably calls their ideology democratic socialism, or social democracy, though few high-level representatives have invoked socialism since Olof Palme (prime minister 1969-76, and again 1982-1986, assassinated 1986).[7] The party supports social welfare provision paid for by progressive taxation. The party supports a social corporatist economy involving the institutionalization of a social partnership system between capital and labour economic interest groups, with government oversight to resolve disputes between the two factions.[8] In recent times they have become strong supporters of egalitarianism, and maintain a strong opposition to discrimination and racism.

In 2007, the Social Democrats elected Mona Sahlin as its first female party leader.

On 7 December 2009, the Social Democrats launched a political and electoral coalition known as the Red-Greens together with the Greens and the Left Party. The parties contested the 2010 election on a joint manifesto, but lost the election to the incumbent centre-right coalition The Alliance. On 26 November 2010 the Red-Green alliance was dissolved.[9]

Current status

Currently, the Social Democratic Party has about 100,000 members, with about 2,540 local party associations and 500 workplace associations. It has been the largest party in the Riksdag since 1917. The member base is diverse, but prominently features organized blue-collar workers and public sector employees. The party has a close, historical relationship with the Swedish Trade Union Confederation (LO); but as a corporatist organ, the Social Democratic Party has formed policy in compromise mediation with the employers' federations (primarily the Confederation of Swedish Enterprise and its predecessors) as well as the union federations.

Organisations within the Swedish social democratic movement:

- The National Federation of Social Democratic Women in Sweden (S-kvinnor) organizes women.

- The Swedish Social Democratic Youth League (Sveriges Socialdemokratiska Ungdomsförbund or SSU) organizes youth.

- The Social Democratic Students of Sweden (Socialdemokratiska Studentförbundet) organizes university students.

- The Religious Social Democrats of Sweden (Socialdemokrater för tro och solidaritet) organizes all members with religious beliefs.

- The LGBT Social Democrats of Sweden (HBT-Socialdemokraterna) organizes LGBT-people.

Voter base

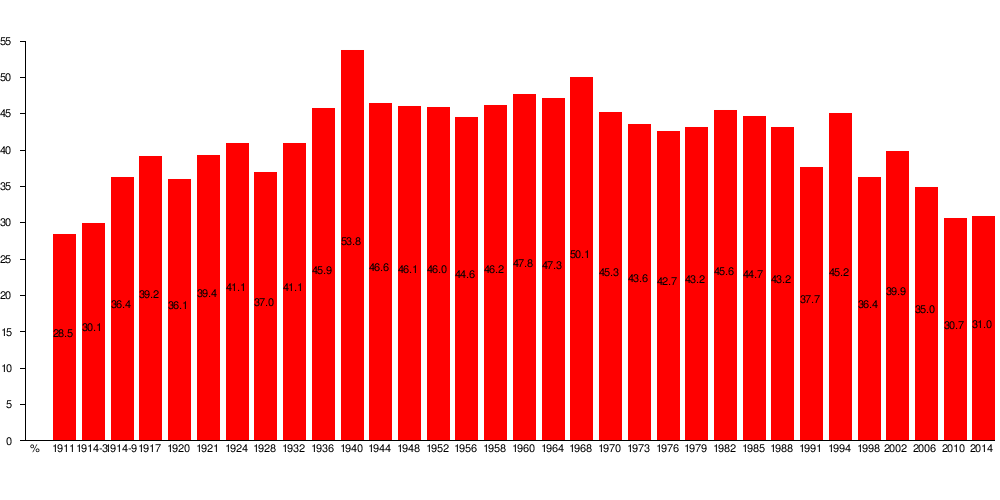

The Swedish Social Democratic Party had its so called "golden age" during the mid 1930's and mid 1980's where in half of all general elections they got between 44.6% to 46.2% (averaging 45.3%) of the votes, making it one of the most successful political parties in the history of the liberal democratic world.[10]

In two of the general elections, the years of 1940 and 1968, they even got more than 50%, however both cases had special circumstances. In 1940 all established Swedish parties, except for the Communist Party, had a coalition government due to the pressures of the second world war, and it can be speculated that it lead to voters most likely wanting one party to be in majority to give a parliament that couldn't be hung. In the year of 1944 the tides of the war had turned and the allied nations looked to win, giving voters more confidence in voting by preference explaining the more normal electoral result of 46.1%. Also there might very well have been some resentment among parts of the public regarding how the Communist Party was held out of the government, and in 1944 they got 10.3%. In the year 1968 the established communist party, most likely due to bad press about the communist overtaking of Czechoslovakia, got a historically very bad result of a mere 3% of the votes, while the Social Democrats enjoyed 50.1% and their own majority in parliament.

Only in a fairly brief period between the elections of the years 1973 to 1979 did the social democrats get below the normal interval between 44.6% to 46.2%, instead scoring an average of 43.2%, and losing in 1976, the first time in 44 years, and again just barely in 1979. However winning back power in 1982 with a normal result of 45.6%.

The voter base consists of a diverse swathe of people throughout Swedish society, although it is particularly strong amongst organised blue-collar workers.[11]

2006 election results

| Social democracy |

|---|

|

|

Development |

|

People |

|

In the 2006 general election, the Social Democratic Party received the smallest share of votes (34.99%) ever in a general election with universal suffrage, resulting in the loss of office to the opposition, the centre-right coalition Alliance for Sweden.[12] Among the support that the Social Democratic Party lost in the 2006 election was the vote of pensioners (down 10% from the 2002 election), and blue-collar trade unionists (down 5%). The combined Social Democratic Party and Left Party vote of citizens with non-Nordic foreign backgrounds sank from 73% in 2002 down to 48% in 2006. Stockholm County typically votes for the centre-right parties. Only 23% of Stockholm City residents voted for the Social Democratic Party in 2006.[13]

Electoral history

| Group | Votes (%) |

Avg. result +/− (pp) |

|---|---|---|

| Members of LO | 51 | +24 |

| On sick leave | 51 | +24 |

| Raised outside Sweden | 49 | +22 |

| Blue-collar workers | 41 | +14 |

| Unemployed | 39 | +12 |

| Local government employees | 34 | +7 |

| Aged 65+ | 34 | +7 |

| Public sector employees | 32 | +5 |

| Government employees | 29 | +2 |

| Females | 29 | +2 |

| Aged 18–21 | 28 | +1 |

| First-time voters | 28 | +1 |

| Aged 31–64 | 27 | 0 |

| Members of TCO | 26 | -1 |

| Students | 25 | -2 |

| Males | 25 | -2 |

| Aged 22–30 | 24 | -3 |

| Farmers | 24 | -3 |

| Private sector employees | 23 | -4 |

| Employed persons | 22 | -5 |

| White-collar workers | 20 | -7 |

| Members of SACO | 18 | -9 |

| Business owners | 16 | -11 |

| All groups (total) | 27 | 0 |

Riksdag

| Election year | # of overall votes |

% of overall vote |

# of overall seats won |

+/– | Government | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1921 | 630,855 | 36,2 (#1) | 93 / 230 |

|

in minority | |

| 1924 | 725,407 | 41,1 (#1) | 104 / 230 |

|

in minority | |

| 1928 | 873,931 | 37,0 (#1) | 90 / 230 |

|

in opposition | |

| 1932 | 1,040,689 | 41,7 (#1) | 104 / 230 |

|

in minority | |

| 1936 | 1,338,120 | 45.9 (#1) | 112 / 230 |

|

in minority | |

| 1940 | 1,546,804 | 53.8 (#1) | 134 / 230 |

|

in majority | |

| 1944 | 1,436,571 | 46.6 (#1) | 115 / 230 |

|

in minority | |

| 1948 | 1,789,459 | 46.1 (#1) | 112 / 230 |

|

in minority | |

| 1952 | 1,729,463 | 46.1 (#1) | 110 / 230 |

|

in coalition | Coalition with Farmers league |

| 1956 | 1,729,463 | 44.6 (#1) | 106 / 231 |

|

in coalition | Coalition with Farmers league |

| 1958 | 1,776,667 | 46.2 (#1) | 111 / 231 |

|

in minority | |

| 1960 | 2,033,016 | 47.8 (#1) | 114 / 232 |

|

in minority | |

| 1964 | 2,006,923 | 47.3 (#1) | 113 / 233 |

|

in minority | |

| 1968 | 2,420,242 | 50.1 (#1) | 125 / 233 |

|

in majority | |

| 1970 | 2,256,369 | 45.3 (#1) | 163 / 350 |

|

in minority | |

| 1973 | 2,247,727 | 43.6 (#1) | 156 / 350 |

|

in minority | |

| 1976 | 2,324,603 | 42.7 (#1) | 152 / 349 |

|

in opposition | |

| 1979 | 2,356,234 | 43.2 (#1) | 154 / 349 |

|

in opposition | |

| 1982 | 2,533,250 | 45.6 (#1) | 166 / 349 |

|

in minority | |

| 1985 | 2,487,551 | 44.7 (#1) | 159 / 349 |

|

in minority | |

| 1988 | 2,321,826 | 43.2 (#1) | 156 / 349 |

|

in minority | |

| 1991 | 2,062,761 | 37.7 (#1) | 138 / 349 |

|

in opposition | |

| 1994 | 2,513,905 | 45.2 (#1) | 161 / 349 |

|

in minority | |

| 1998 | 1,914,426 | 36.4 (#1) | 131 / 349 |

|

in minority | |

| 2002 | 2,113,560 | 39.9 (#1) | 144 / 349 |

|

in minority | |

| 2006 | 1,942,625 | 35.0 (#1) | 130 / 349 |

|

in opposition | |

| 2010 | 1,827,497 | 30.7 (#1) | 112 / 349 |

|

in opposition | |

| 2014 | 1,932,711 | 31.0 (#1) | 113 / 349 |

|

in minority coalition | Coalition with Green party |

European Parliament

| Election year | # of overall votes |

% of overall vote |

# of overall seats won |

+/− | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1995 | 752,817 | 28.1 (#1) | 7 / 22 |

||

| 1999 | 657,497 | 26.0 (#1) | 6 / 22 |

|

|

| 2004 | 616,963 | 24.6 (#1) | 5 / 19 |

|

|

| 2009 | 773,513 | 24.4 (#1) |

|

|

|

| 2014 | 899,074 | 24.2 (#1) | 5 / 20 |

|

Political impact and history

The party's first chapter in its statutes says "the intension of the Swedish Social Democratic Labour Party is the struggle towards the Democratic Socialism," that is, a society with a democratic economy based on the socialist principle, "From each according to his ability, to each according to his need." Since the party held power of office for a majority of terms after its founding in 1889 through 2003, the ideology and policies of the Social Democratic Party (SAP) have had strong influence on Swedish politics.[15] The Swedish social democratic ideology is partially an outgrowth of the strong and well-organized 1880s and 1890s working class emancipation, temperance, and religious folkrörelser (folk movements), by which peasant and workers' organizations penetrated state structures early on and paved the way for electoral politics. In this way, Swedish social-democratic ideology is inflected by a socialist tradition foregrounding widespread and individual human development.[16] Gunnar Adler-Karlsson (1967) confidently likened the social democratic project to the successful social democratic effort to divest the king of all power but formal grandeur: "Without dangerous and disruptive internal fights…After a few decades they (capitalists) will then remain, perhaps formally as kings, but in reality as naked symbols of a passed and inferior development state."[17] However, so far this socialist ambition has not materialised.

Liberalism

Liberalism has also strongly infused social-democratic ideology. Liberalism has oriented social democratic goals to security, as where Tage Erlander, prime minister from 1946 to 1969, described security as "too big a problem for the individual to solve with only his own power".[18] Up to the 1980s, when neoliberalism began to provide an alternative, aggressively pro-capitalist model for ensuring social quiescence, the SAP was able to secure capital's co-operation by convincing capital that it shared the goals of increasing economic growth and reducing social friction. For many social democrats, Marxism is loosely held to be valuable for its emphasis on changing the world for a more just, better future.[19] In 1889, Hjalmar Branting, leader of the SAP from its founding to his death in 1925, asserted, "I believe … that one benefits the workers...so much more by forcing through reforms which alleviate and strengthen their position, than by saying that only a revolution can help them."[20] Some observers have argued that this liberal aspect has hardened into increasingly neoliberal ideology and policies, gradually maximizing the latitude of powerful market actors.[21] Certainly, neoclassical economists have been firmly nudging the Social Democratic Party into capitulating to most of capital's traditional preferences and prerogatives, which they term "modern industrial relations".[22] Both socialist and liberal aspects of the party were influenced by the dual sympathies of early leader Hjalmar Branting, and manifest in the party's first actions: reducing the work day to eight hours and establishing the franchise for working-class people.

While some commentators have seen the party lose focus with the rise of SAP neoliberal study groups, the Swedish Social Democratic Party has for many years appealed to Swedes as innovative, capable, and worthy of running the state.[23] The Social Democrats became one of the most successful political parties in the world, with some structural advantages in addition to their auspicious birth within vibrant folkrörelser. At the close of the nineteenth century, liberals and socialists had to band together to augment establishment democracy, which was at that point embarrassingly behind in Sweden; they could point to formal democratic advances elsewhere to motivate political action.[24] In addition to being small, Sweden was a semi-peripheral country at the beginning of the twentieth century, considered unimportant to competing global political factions; so it was permitted more independence, while soon the existence of communist and capitalist superpowers allowed social democracy to flourish in the geo-political interstices.[25] The SAP has the resource of sharing ideas and experiences, and working with its sister parties throughout the Nordic countries. Sweden could also borrow and innovate upon ideas from English-language economists, which was an advantage for the Social Democrats in the Great Depression; but more advantageous for the bourgeois parties in the 1980s and afterward. While the SAP has not been innocent of repressing communists,[26] the party has overall benefitted, in government coalition and in avoiding severe stagnation and drift, by engaging in relatively constructive relationships with the more radical Left Party and the Green Party. The early SAP had internal resources as well, in creative politicians with brilliant tactical minds, and similarly creative labor economists at their disposal.

Revisionism

Among the social movement tactics of the Swedish Social Democratic Party in the twentieth century was its redefinition of "socialization" from "common ownership of the means of production" to increasing "democratic influence over the economy."[27] Starting out in a socialist-liberal coalition fighting for the vote, the Swedish Social Democrats defined socialism as the development of democracy—political and economic.[28] On that basis they could form coalitions, innovate, and govern where other European social democratic parties became crippled and crumbled under Right-wing regimes. The Swedish Social Democrats could count the middle class among their solidaristic working class constituency by recognizing the middle class as "economically dependent", "working people", or among the "progressive citizens", rather than as sub-capitalists.[29] "The party does not aim to support and help [one] working class at the expense of the others," the Social Democratic congress of 1932 established. In fact, with social democratic policies that refrained from supporting inefficient and low-profit businesses in favor of cultivating higher-quality working conditions, as well as a strong commitment to public education, the middle class in Sweden became so large that the capitalist class has remained concentrated.[30] Not only did the SAP fuse the growing middle class into their constituency, they also ingeniously forged periodic coalitions with small-scale farmers (as members of the "exploited classes") to great strategic effect.[31] The SAP version of socialist ideology allowed them to maintain a prescient view of the working class: "[The SAP] does not question … whether those who have become capitalism's victims … are industrial workers, farmers, agricultural laborers, forestry workers, store clerks, civil servants or intellectuals", asserted the party's 1932 election manifesto.[32]

While the SAP has worked more or less constructively with more radical Left parties in Sweden, the Social Democrats have borrowed from socialists some of their discourse, and decreasingly, the socialist understanding of the structurally compromised position of labor under capitalism. Even more creatively, the Social Democrats commandeered selected, transcendental images from such nationalists as Rudolf Kjellen (1912), very effectively undercutting fascism's appeal in Sweden.[33] In this way, Per Albin Hansson declared that "there is no more patriotic party than the [SAP since] the most patriotic act is to create a land in which all feel at home," famously igniting Swedes' innermost longing for transcendence with the idea of the Folkhem (1928), or People's Home. The Social Democratic Party promoted Folkhemmet as a socialist home at a point in which the party turned its back on working class struggle and the policy tool of nationalization.[34] "The expansion of the party to a people's party does not mean and must not mean a watering down of socialist demands," Hansson soothed.[35]

- "The basis of the home is community and togetherness. The good home does not recognize any privileged or neglected members, nor any favorite or stepchildren. In the good home there is equality, consideration, co-operation, and helpfulness. Applied to the great people's and citizens' home this would mean the breaking down of all the social and economic barriers that now separate citizens into the privileged and the neglected, into the rulers and the dependents, into the rich and the poor, the propertied and the impoverished, the plunderers and the plundered. Swedish society is not yet the people's home. There is a formal equality, equality of political rights, but from a social perspective, the class society remains, and from an economic perspective the dictatorship of the few prevails" (Hansson 1928).[36]

Social democracy

The Social Democratic Party is generally recognized as the main architect of the progressive taxation, fair trade, low-unemployment, Active Labor Market Policies (ALMP)-based Swedish welfare state that was developed in the years after World War II. Sweden emerged sound from the Great Depression with a brief, successful "Keynesianism-before Keynes" economic program advocated by Ernst Wigforss, a prominent Social Democrat who educated himself in economics by studying the work of the British radical Liberal economists. The social democratic labor market policies (ALMPs) were developed in the 1940s and 1950s by LO (Landsorganisationen i Sverige, the blue-collar union federation) economists Gösta Rehn and Rudolf Meidner.[37] The Rehn-Meidner model featured the centralized system of wage bargaining that aimed to both set wages at a "just" level and promote business efficiency and productivity. With the pre-1983 cooperation of capital and labor federations that bargained independently of the state, the state determined that wages would be higher than the market would set in firms that were inefficient or uncompetitive and lower than the market would set in firms that were highly productive and competitive. Workers were compensated with state-sponsored retraining and relocating; as well, the state reformed wages to the goal of "equal pay for equal work", eliminated unemployment ("the reserve army of labor") as a disciplinary device, and kept incomes consistently rising, while taxing progressively and pooling social wealth to deliver services through local governments.[38] Social Democratic policy has traditionally emphasized a state spending structure whereby public services are supplied via local government, as opposed to emphasizing social insurance program transfers.[39]

These social democratic policies have had international influence. The early Swedish "red-green" coalition encouraged Nordic-networked socialists in the state of Minnesota, in the U.S., to dedicate efforts to building a similarly potent labor-farmer alliance that put the socialists in the governorship, ran model innovative statewide anti-racism programs in the early years of the twentieth century, and enabled federal forest managers in Minnesota to practice a precocious ecological-socialism, before Democratic Party reformers appropriated the Minnesota Farmer-Labor Party infrastructure to the liberal Democratic Party in 1944.[40]

At a 27 July 1960 Republican National Committee breakfast in Chicago, President Dwight D. Eisenhower said, probably referring to Sweden, "Only in the last few weeks, I have been reading quite an article on the experiment of almost complete paternalism in a friendly European country. This country has a tremendous record for socialistic operation, following a socialistic philosophy, and the record shows that their rate of suicide has gone up almost unbelievably and I think they were almost the lowest nation in the world for that. Now, they have more than twice our rate. Drunkenness has gone up. Lack of ambition is discernible on all sides."[41]

Under the Social Democrats' administration, Sweden retained neutrality, as a foreign policy guideline, during the wars of the twentieth century, including the Cold War. Neutrality preserved the Swedish economy and boosted Sweden's economic competitiveness in the first half of the twentieth century, as other European countries' economies were devastated by war.[42] Under Olof Palme's Social Democratic leadership Sweden further aggravated the hostility of United States political conservatives when Palme openly denounced US aggression in Vietnam. U.S. President Richard Nixon suspended diplomatic ties with the social democratic country.[43] In 2003, top-ranking Social Democratic Party politician Anna Lindh—who criticized the U.S. invasion of Iraq, as well as both Israeli and Palestinian atrocities, and who was the lead figure promoting the European Union in Sweden—was assassinated in public in Stockholm. As Lindh was to succeed Goran Persson in the party leadership, her death was deeply disruptive to the party as well as to the campaign to promote the adoption of the EMU (euro) in Sweden. The neutrality policy has changed with the contemporary ascendance of the bourgeois coalition, and Sweden has committed troops to support the US and UK's interventions in Afghanistan. Under Social Democratic governance relatively strong overseas humanitarian programs and a comparatively well-developed refugee program have been implemented, and frequently reformed.[44]

Rehn-Meidner macroeconomics to neoliberalism

Because the Rehn-Meidner model allowed capitalists owning very productive and efficient firms to retain excess profits at the expense of the firms' workers, thus exacerbating inequality, workers in these firms began to agitate for a share of the profits in the 1970s, just as women working in the state sector began to assert pressure for better wages. Meidner established a study committee that came up with a 1976 proposal that entailed transferring the excess profits into investment funds controlled by the workers in the efficient firms, with the intention that firms would create further employment and pay more workers higher wages, rather than increasing the wealth of company owners and managers.[45] Capitalists immediately distinguished this proposal as socialism, and launched an unprecedented opposition—including calling off the class compromise established in the 1938 Saltsjöbaden Agreement.[46]

The 1980s were a very turbulent time in Sweden that initiated the occasional decline of Social Democratic Party rule. In the 1980s, pillars of Swedish industry were massively restructured. Shipbuilding was discontinued, wood pulp was integrated into modernized paper production, the steel industry was concentrated and specialized, and mechanical engineering was digitalized.[47] In 1986, one of the Social Democratic Party's strongest champions of egalitarianism and democracy, Olof Palme was assassinated. Swedish capital was increasingly moving Swedish investment into other European countries as the European Union coalesced, and a hegemonic consensus was forming among the elite financial community: progressive taxation and pro-egalitarian redistribution became economic heresy.[48] A leading proponent of capital's cause at the time, Social Democrat Finance Minister Kjell-Olof Feldt reminisced in an interview, "The negative inheritance I received from my predecessor Gunnar Sträng (Minister of Finance, 1955–1976) was a strongly progressive tax system with high marginal taxes. This was supposed to bring about a just and equal society. But I eventually came to the opinion that it simply didn't work out that way. Progressive taxes created instead a society of wranglers, cheaters, peculiar manipulations, false ambitions and new injustices. It took me at least a decade to get a part of the party to see this."[49] With the capitalist confederation's defection from the 1938 Saltsjöbaden Agreement and Swedish capital investing in other European countries rather than Sweden, as well as the global rise of neoliberal political-economic hegemony, the Social Democratic Party backed away from the progressive Meidner reform.[50]

The economic crisis in the 1990s has been widely cited in the Anglo-American press as a social democratic failure, but it is important to note not only did profit rates begin to fall worldwide after the 1960s,[51] also this period saw neoliberal ascendance in Social Democratic ideology and policies as well as the rise of bourgeois coalition rule in place of the Social Democrats. 1980s Social Democratic neoliberal measures—such as depressing and deregulating the currency to prop up Swedish exports during the economic restructuring transition, dropping corporate taxation and taxation on high income-earners, and switching from anti-unemployment policies to anti-inflationary policies—were exacerbated by international recession, unchecked currency speculation, and a centre-right government led by Carl Bildt (1991–1994), creating the fiscal crisis of the early 1990s.[52]

When the Social Democrats returned to power in 1994, they responded to the fiscal crisis[53] by stabilizing the currency—and by reducing the welfare state and privatizing public services and goods, as governments did in many countries influenced by Milton Friedman, the Chicago Schools of political and economic thought, and the neoliberal movement. Social Democratic Party leaders—including Göran Persson, Mona Sahlin, and Anna Lindh—promoted European Union (E.U.) membership, and the Swedish referendum passed by 52–48% in favor of joining the E.U. on 14 August 1994. Bourgeois leader Lars Leijonborg at his 2007 retirement could recall the 1990s as a golden age of liberalism in which the Social Democrats were under the expanding influence of the Liberal Party and its partners in the bourgeois political coalition. Leijonborg recounted neoliberal victories such as the growth of private schooling and the proliferation of private, for-profit radio and television.[54]

21st century

However, many of the aspects of the social-democratic welfare state continued to function at a high level, due in no small part to the high rate of unionization in Sweden, the independence of unions in wage-setting, and the exemplary competency of the feminized public sector workforce,[55] as well as widespread public support. The Social Democrats initiated studies on the effects of the neoliberal changes, and the picture that emerged from those findings allowed the party to reduce many tax expenditures, slightly increase taxes on high income-earners, and significantly reduce taxes on food. The Social Democratic Finance Minister increased spending on child support and continued to pay down the public debt.[56] By 1998 the Swedish macro-economy recovered from the 1980s industrial restructuring and the currency policy excesses.[47] At the turn of the twenty-first century, Sweden has a well-regarded, generally robust economy, and the average quality of life, after government transfers, is very high, inequality is low (the Gini coefficient is .28), and social mobility is high (compared to the affluent Anglo-American and Central European countries).[48]

The Social Democratic Party pursues environmentalist and feminist policies which promote healthful and humane conditions. Feminist policies formed and implemented by the Social Democratic Party and the Left Party and the Greens (which made an arrangement with the Social Democrats to support the government, while not forming a coalition), include paid maternity and paternity leave, high employment for women in the public sector, combining flexible work with living wages and benefits, providing public support for women in their traditional responsibilities for care giving, and policies to stimulate women's political participation and leadership. Reviewing policies and institutional practices for their impact on women had become common in social democratic governance.[57]

The Social Democratic Party was defeated in 2006 by the centre-right Alliance for Sweden coalition. Mona Sahlin succeeded Göran Persson as party leader in 2007, becoming the party's first female party leader. Prior to the 2010 general election, the Social Democratic Party formed a cooperation with the Green Party and the Left Party culminating in the Red-Green Alliance. The cooperation was dissolved following another defeat in 2010, throwing the party in to its longest period in opposition since before 1936. Mona Sahlin announced her resignation following the 2010 defeat and she was succeeded by Håkan Juholt in 2011. Initially his leadership gave a rise in the opinion polls before being involved in a scandal surrounding benefits from parliament which, after a period, culminated in his resignation. Sahlin and Juholt become the first party leaders since Claes Tholin, who was party leader 1896-1907, to not become Prime Ministers.

Stefan Löfven, elected by the party board, succeeded Juholt as party leader. Löfven led the Social Democratic Party into the 2014 European Parliament election which resulted in the partys worst electoral results at national level since universal suffrage was introduced in 1921. He then led the party into the 2014 general election which resulted in the party's second worst election result to the Riksdag since universal suffrage was introduced in 1921. With a hung parliament, Löfven formed a minority coalition government with the Green Party. On 2 October 2014, the Riksdag approved Löfven to become the country's Prime Minister,[58] and he took office on 3 October 2014 alongside his Cabinet. The Social Democratic Party and the Green Party voted in favour of Löfvén becoming Prime Minister, while close ally the Left Party abstained. The oppositional Alliance-parties also abstained while far-right Sweden Democrats voted against.

International affiliations

The party was a member of the Labour and Socialist International between 1923 and 1940.[59]

The current-day party is a member of the Progressive Alliance, the Party of European Socialists[60] and SAMAK, as well as being an observer affiliate of the Socialist International.[61]

Party Leaders

| Party Leader | Period | Party Secretary | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Claes Tholin | |

|

Karl Magnus Ziesnitz, Carl Gustaf Wickman |

| First party leader after collective leadership. | |||

| Hjalmar Branting | |

|

Carl Gustaf Wickman, Fredrik Ström, Gustav Möller |

| Prime Minister 1920, 1921-1923 and 1924-1925. Died in office. | |||

| Per Albin Hansson | |

|

Gustav Möller, Torsten Nilsson, Sven Andersson |

| Prime Minister 1932-1936 and 1936-1946. Died in office. | |||

| Tage Erlander | |

|

Sven Andersson, Sven Aspling, Sten Andersson |

| Prime Minister 1946-1969. Longest-serving Prime Minister in Swedish history. | |||

| Olof Palme | |

|

Sten Andersson, Bo Toresson |

| Prime Minister 1969-1976 and 1982-1986. Assassinated. | |||

| Ingvar Carlsson | |

|

Bo Toresson, Mona Sahlin, Leif Linde |

| Prime Minister 1986-1991 and 1994-1996. | |||

| Göran Persson | |

|

Ingela Thalén, Lars Stjernkvist, Marita Ulvskog |

| Prime Minister 1996-2006. | |||

| Mona Sahlin | |

|

Marita Ulvskog, Ibrahim Baylan |

| First female party leader. | |||

| Håkan Juholt | |

|

Carin Jämtin |

| Resigned after a scandal. | |||

| Stefan Löfven | |

|

Carin Jämtin, Lena Rådström Baastad |

| Prime Minister 2014- | |||

See also

- Prime Minister of Sweden

- Government of Sweden

- Parliament of Sweden

- Elections in Sweden

- Politics of Sweden

- Welfare in Sweden

- ABF

Literature

- Andersson, Jenny (2006). Between growth and security: Swedish social democracy from a strong society to a third way. Manchester University Press.

- Johansson, Karl Magnus; Von Sydow, Göran (2011). Swedish social democracy and European integration: Enduring divisions. Social Democracy and European Integration: The politics of preference formation. Routledge. pp. 157–187.

- Therborn, Göran & Kjellberg, Anders & Marklund, Staffan & Öhlund, Ulf (1978) "Sweden Before and After Social Democracy: A First Overview", Acta Sociologica 1978 – supplement, pp. 37–58.

- Therborn, Göran (1984) "The Coming of Swedish Social Democracy", in E. Collotti (ed.) Il movimiento operaio tra le due guerre, Milano: Annali della Fondazione Giangiacomo Feltrinelli 1983/84, pp. 527–593

- Östberg, Kjell (2012). Swedish Social Democracy After the Cold War: Whatever Happened to the Movement?. Social Democracy After the Cold War. Athabasca University Press. pp. 205–234.

References

- ↑ Holmqvist, Anette; Röstlund, Lisa (December 8, 2014). "Medlemsström till partierna i krisen". Aftonbladet (in Swedish).

- ↑ Merkel, Wolfgang; Alexander Petring; Christian Henkes; Christoph Egle (2008). Social Democracy in Power: The Capacity to Reform. London: Taylor & Francis. pp. 8, 9. ISBN 0-415-43820-9.

- 1 2 Wolfram Nordsieck. "Parties and Elections in Europe: The database about parliamentary elections and political parties in Europe, by Wolfram Nordsieck". parties-and-elections.eu. Retrieved 13 September 2014.

- ↑ "2014: Val till landstingsfullmäktige – Valda", Valmyndigheten, 2014-09-28

- ↑ "2014: Val till kommunfullmäktige – Valda", Valmyndigheten, 2014-09-26

- ↑ Lamb, Peter; Docherty, James C. (2006), Historical Dictionary of Socialism (Second ed.), Scarecrow Press

- ↑ http://www.ibtimes.co.uk/who-killed-swedish-pm-olof-palme-five-best-conspiracy-theories-1438035

- ↑ Gerassimos Moschonas, Gregory Elliot (translator). In the Name of Social Democracy: The Great Transformation, 1945 to the Present. London, United Kingdom; New York, United States: Verso, 2002. P. 64–69.

- ↑ Stenberg, Ewa (26 November 2012). "Det borde bara ha varit vi och S". Dagens Nyheter (in Swedish). Archived from the original on 18 October 2012. Retrieved 21 January 2012.

- ↑ Göran Therborn "A Unique Chapter in the History of Democracy: The Swedish Social Democrats", in. K. Misgeld et al (eds.), Creating Social Democracy, University Park Pa., Penn State University Press, 1996

- ↑ Hur röstade LO-medlemmar? Archived 5 August 2012 at the Wayback Machine., Social bakgrund – sysselsättning relaterat till partiröst SVT Valu (Parliamentary election exit poll) Archived 30 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ (Swedish)Historisk statistik över valåren 1910–2006, from Statistics Sweden, accessed 14 June 2007

- ↑ Sundström, Eric. 2006. "Election analysis: Why we lost." http://ericsundstrom.blogspot.com/2006_09_01_archive.html.

- ↑ Holmberg, Sören; Näsman, Per; Wänström, Kent (2010). Riksdagsvalet 2010 Valu (PDF) (Report). Sveriges Television. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 June 2011. Retrieved 2010-09-30.

- ↑ Samuelsson, Kurt. 1968. From Great Power to Welfare State: 300 Years of Swedish Social Development. London: George Allen and Unwin.

- ↑ Alapuro, Risto. 1999. "On the repertoires of collective action in France and the Nordic countries." TBD.

- ↑ Pp. 101–102 in Adler-Karlsson, Gunnar. 1967. Functional Socialism. Stockholm: Prisma. Cited on p. 196 in Berman, Sheri. 2006. The Primacy of Politics: Social Democracy and the Making of Europe's Twentieth Century. Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, MA.

- ↑ Pp. 258–259 in Erlander, Tage. 1956 SAP Congress Protokoll, in Från Palm to Palme: Den Svenska Socialdemokratins Program. Stockholm: Raben and Sjögren. Cited in Berman 2006: 196. Abrahamson, Peter. "The Scandinavian model of welfare." TBD

- ↑ Berman 2006: 153

- ↑ in a letter to Axel Danielsson in jail (1889), reprinted on p. 189 in Från Palm to Palme: Den Svenska Socialdemokratins Program. Stockholm: Raben and Sjögren. Cited in Berman 2006:156.

- ↑ Korpi, Walter and Stern. 2004. "Women's employment in Sweden: Globalization, deindustrialization, and the labor market experiences of Swedish Women 1950-2000." Globalife Working Paper No. 51. Korpi, Walter and Joakim Palme. 2003. "New politics and class politics in the conext of austerity and globalization: Welfare state regress in 18 countries 1975-1995." Stockholm: Stockholm University. Korpi, Walter. 2003. "Welfare state regress in Western Europe: Politics, Institutions, Globalization, and Europeanization." Annual Review of Sociology 29: 589–609. Korpi, Walter. 1996. "Eurosclerosis and the sclerosis of objectivity: On the role of velues among economic policy experts." Economic Journal 106: 1727–1746. Notermans, Ton. 1997. "Social democracy and external constraints." Pp. 201–239 in Spaces of Globalization: Reasserting the Power of the Local, edited by K.R. Cox. New York: The Guildord Press. Olsen, Gregg. 2002. The Politics of the Welfare State: Canada, Sweden, and the United States. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Pred, Alan. 2000. Even in Sweden: Racisms, Racialized Spaces, and the Popular Geographical Imagination. Berkeley: University of California Press. Ryner, Magnus. TBD. SAF. 1993. The Swedish Employers' Confederation: An Influential Voice in Public Affairs. Stockholm: SAF. Stephens, John D. 1996. "The Scandinavian welfare states: Achievements, crisis, and prospects." Pp. 32–65 in Welfare States in Transition: National Adaptations in Global Economies, edited by Gosta Esping-Anderson. Wennerberg, Tor. 1995. "Undermining the welfare state in Sweden." ZMagazine, June. Accessed at .

- ↑ Vartiainen, Juhana. 2001. "Understanding Swedish Social Democracy: Victims of Success?" pp. 21–52 in Social Democracy in Neoliberal Times, edited by Andrew Glyn. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- ↑ Berman 2006: 153–154, 156

- ↑ Berman 2006: 159

- ↑ Berman 2006: 152

- ↑ Cohen, Peter. 1994. "Sweden: The Model That Never Was." Monthly Review, July–August.

- ↑ Berman 2006: 196

- ↑ Berman 2006: 153, 155

- ↑ Berman 2006: 157

- ↑ Stevenson, Paul. 1979. "Swedish Capitalism: An Essay Review." Crime, Law, and Social Change 3(2).

- ↑ Berman 2006: 158–159; 166–167

- ↑ Reprinted in Håkansson, edl, Svenska Valprogram, Vol. 2, and cited in Berman 2006: 173

- ↑ Berman 2006: 163–164; 170

- ↑ Meidner, Rudolf. 1993. "Why did the Swedish model fail?" The Socialist Register 29: 211–228. http://socialistregister.com/index.php/srv/article/view/5630

- ↑ Hansson, Per Albin. "Folk och Klass": 80. Cited in Berman 2006: 166

- ↑ Berkling. Från Fram till Folkhemmet: 227–230; Tilton. The Political Theory of Swedish Social Democracy: 126–127.

- ↑ Carroll, Eero. 2003. "International organisations and welfare states at odds? The case of Sweden." Pp. 75–88 in The OECD and European Welfare States, edited by Klaus Armingeon and Michelle Beyeler. Northampton, MA: Edward Elgar; Esping-Anderson, Gösta. 1985. Politics Against Markets: The Social-Democratic Road to Power. Princeton: Princeton University Press; Korpi, Walter. 1992. Halkar Sverige efter? Sveriges ekonomiska tillväxt 1820–1990 i jämförande belysning, Stockholm: Carlssons; Olsen, Gregg M. 1999. "Half empty or half full? The Swedish welfare state in transition." Canadian Review of Sociology & Anthropology, 36 (2): 241–268; Olsen, Gregg. 2002. The Politics of the Welfare State: Canada, Sweden, and the United States. Oxford: Oxford University Press; Samuelsson, Kurt. 1968. From Great Power to Welfare State: 300 years of Swedish Social Development. London: George Allen and Unwin.

- ↑ Berman, Sheri. 2006. The Primacy of Politics: Social Democracy and the Making of Europe's Twentieth Century. Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, MA

- ↑ Abrahamson, Peter. 1999. "The Scandinavian model of welfare." TBD

- ↑ Delton, Jennifer A. 2002. Making Minnesota Liberal. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota; Hudson, Mark. 2007. The Slow Co-Production of Disaster: Wildfire, Timber Capital, and the United States Forest Service. Eugene, OR: University of Oregon.

- ↑ Eisenhower, Dwight D. 1960. From Public Papers of the President. Dwight D. Eisenhower Library. Available online at http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/?pid=11891#ixzz1fU73Watz

- ↑ Esping-Anderson, Gosta. 1985. Politics Against Markets: The Social-Democratic Road to Power. Princeton: Princeton University Press; Samuelsson, Kurt. 1968. From Great Power to Welfare State: 300 Years of Swedish Social Development. London: George Allen and Unwin.

- ↑ Andersson, Stellan. "Olof Palme och Vietnamfrågan 1965–1983" (in Swedish). olofpalme.org. Retrieved 27 February 2008.

- ↑ Integrationsverket website TBD; Alund, Aleksandra & Carl-Ulrik Schierup TBD; Mulinari, Diana and Anders Neergaard. 2004. Den Nya Svenska Arbetarklassen. Borea: Borea Bokforlag.

- ↑ Michael Newman (25 July 2005), Socialism: A Very Short Introduction, Oxford University Press

- ↑ Berman 2006

- 1 2 Krantz, Olle and Lennart Schön. 2007. Swedish Historical National Accounts, 1800–2000. Lund: Almqvist and Wiksell International.

- 1 2 Steinmo, Sven. 2001. "Bucking the Trend? The Welfare State and Global Economy: The Swedish Case Up Close." University of Colorado, 18 December.

- ↑ Sjöberg, T. (1999). Intervjun: Kjell-Olof Feldt [Interview: Kjell-Olof Feldt]." Playboy Skandinavia (5): 37–44.

- ↑ Berman 2006: 198

- ↑ McNally, David. 1999. "Turbulence in the World Economy." Monthly Review 51(2). http://www.monthlyreview.org/699mcnal.htm. Bowles, Samuel, David M. Gordon, and Thomas E. Weisskopf. 1989. "Business Ascendancy and Economic Impasse: A Structural Retrospective on Conservative Economics, 1979–87." Journal of Economic Perspectives 3(1): 107–134.

- ↑ Englund, P. 1990. "Financial deregulation in Sweden." European Economic Review 34 (2–3): 385–393. Korpi TBD. Meidner, R. 1997. "The Swedish model in an era of mass unemployment." Economic and Industrial Democracy 18 (1): 87–97. Olsen, Gregg M. 1999. "Half empty or half full? The Swedish welfare state in transition." Canadian Review of Sociology & Anthropology, 36 (2): 241–268.

- ↑ Between 1990 and 1994, per capita income declined by approximately 10% – https://web.archive.org/web/20070627060024/http://hdr.undp.org/docs/publications/ocational_papers/oc26c.htm. Archived from the original on 27 June 2007. Retrieved 5 July 2007. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ The Local, 13 June 2007. http://www.thelocal.se.

- ↑ Olsen, 2002.

- ↑ Steinmo, Sven. 2001. "Bucking the Trend? The Welfare State and Global Economy: The Swedish Case Up Close." University of Colorado, 18 December. Carroll, Eero. 2004. "International Organizations and Welfare States at Odds? The Case of Sweden." The OECD and European Welfare States. Edited by Klaus Armingeon and Michelle Beyer. Northampton, MA: Edward Egar.

- ↑ Acker, Joan. Hobson, Barbara. Sainsbury, Diane. 1999. "Gender and the making of the Norwegian and Swedish welfare states." Pp. 153–168 in Comparing Social Welfare Systems in Nordic Europe and France. Nantes: Maison des Sciences de l'Homme Ange-Guepin. Älund, Aleksandra and Carl-Ulrik Schierup. 1991. Paradoxes of multiculturalism. Aldershot: Avebury.

- ↑ "Sverige har fått en ny statsminister". dn.se. Retrieved 2 October 2014.

- ↑ Kowalski, Werner. Geschichte der sozialistischen arbeiter-internationale: 1923 – 19. Berlin: Dt. Verl. d. Wissenschaften, 1985. p. 322

- ↑ "Parties – PES". PES. Retrieved 13 September 2014.

- ↑ "Member Parties of the Socialist International". Socialist International. Retrieved 13 September 2014.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Socialdemokraterna. |

- Socialdemokraterna (English)

- United States Department of State – Sweden

- The Swedish Labor Movement Archive and Library (Arbetarrorelsens Arkiv och Bibliotek)