Small-world network

Hubs are bigger than other nodes Average degree= 3.833

Average shortest path length = 1.803.

Clustering coefficient = 0.522

Average degree = 2.833

Average shortest path length = 2.109.

Clustering coefficient = 0.167

| Network science | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Network types | ||||

| Graphs | ||||

|

||||

| Models | ||||

|

||||

| ||||

|

||||

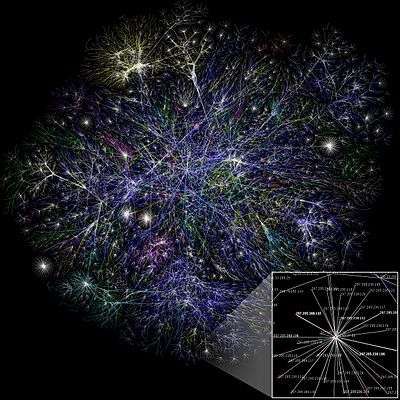

A small-world network is a type of mathematical graph in which most nodes are not neighbors of one another, but the neighbors of any given node are likely to be neighbors of each other and most nodes can be reached from every other node by a small number of hops or steps. Specifically, a small-world network is defined to be a network where the typical distance L between two randomly chosen nodes (the number of steps required) grows proportionally to the logarithm of the number of nodes N in the network, that is:[1]

while the clustering coefficient is not small. In the context of a social network, this results in the small world phenomenon of strangers being linked by a short chain of acquaintances. Many empirical graphs show the small-world effect, e.g., social networks, the underlying architecture of the Internet, wikis such as Wikipedia, and gene networks.

A certain category of small-world networks were identified as a class of random graphs by Duncan Watts and Steven Strogatz in 1998.[2] They noted that graphs could be classified according to two independent structural features, namely the clustering coefficient, and average node-to-node distance (also known as average shortest path length). Purely random graphs, built according to the Erdős–Rényi (ER) model, exhibit a small average shortest path length (varying typically as the logarithm of the number of nodes) along with a small clustering coefficient. Watts and Strogatz measured that in fact many real-world networks have a small average shortest path length, but also a clustering coefficient significantly higher than expected by random chance. Watts and Strogatz then proposed a novel graph model, currently named the Watts and Strogatz model, with (i) a small average shortest path length, and (ii) a large clustering coefficient. The crossover in the Watts–Strogatz model between a "large world" (such as a lattice) and a small world was first described by Barthelemy and Amaral in 1999.[3] This work was followed by a large number of studies, including exact results (Barrat and Weigt, 1999; Dorogovtsev and Mendes; Barmpoutis and Murray, 2010). Braunstein [4] found that for weighted ER networks where the weights have a very broad distribution, the optimal path scales becomes significantly longer and scales as N^{1/3}.

Properties of small-world networks

Small-world networks tend to contain cliques, and near-cliques, meaning sub-networks which have connections between almost any two nodes within them. This follows from the defining property of a high clustering coefficient. Secondly, most pairs of nodes will be connected by at least one short path. This follows from the defining property that the mean-shortest path length be small. Several other properties are often associated with small-world networks. Typically there is an over-abundance of hubs - nodes in the network with a high number of connections (known as high degree nodes). These hubs serve as the common connections mediating the short path lengths between other edges. By analogy, the small-world network of airline flights has a small mean-path length (i.e. between any two cities you are likely to have to take three or fewer flights) because many flights are routed through hub cities.

This property is often analyzed by considering the fraction of nodes in the network that have a particular number of connections going into them (the degree distribution of the network). Networks with a greater than expected number of hubs will have a greater fraction of nodes with high degree, and consequently the degree distribution will be enriched at high degree values. This is known colloquially as a fat-tailed distribution. Graphs of very different topology qualify as small-world networks as long as they satisfy the two definitional requirements above.

Network small-worldness has been quantified by comparing clustering and path length of a given network to an equivalent random network with same degree on average.[5] Another method for quantifying network small-worldness utilizes the original definition of the small-world network comparing the clustering of a given network to an equivalent lattice network and its path length to an equivalent random network.[6] The small-world measure () is defined as[7]

R. Cohen and Havlin[8][9] showed analytically that scale-free networks are ultra-small worlds. In this case, due to hubs, the shortest paths become significantly smaller and scale as

Examples of small-world networks

Small-world properties are found in many real-world phenomena, including websites with navigation menus, food chains, electric power grids, metabolite processing networks, networks of brain neurons, voter networks, telephone call graphs, and social influence networks.

Networks of connected proteins have small world properties such as power-law obeying degree distributions.[10] Similarly transcriptional networks, in which the nodes are genes, and they are linked if one gene has an up or down-regulatory genetic influence on the other, have small world network properties.[11]

Examples of non-small-world networks

In another example, the famous theory of "six degrees of separation" between people tacitly presumes that the domain of discourse is the set of people alive at any one time. The number of degrees of separation between Albert Einstein and Alexander the Great is almost certainly greater than 30[12] and this network does not have small-world properties. A similarly constrained network would be the "went to school with" network: if two people went to the same college ten years apart from one another, it is unlikely that they have acquaintances in common amongst the student body.

Similarly, the number of relay stations through which a message must pass was not always small. In the days when the post was carried by hand or on horseback, the number of times a letter changed hands between its source and destination would have been much greater than it is today. The number of times a message changed hands in the days of the visual telegraph (circa 1800–1850) was determined by the requirement that two stations be connected by line-of-sight.

Tacit assumptions, if not examined, can cause a bias in the literature on graphs in favor of finding small-world networks (an example of the file drawer effect resulting from the publication bias).

Network robustness

It is hypothesized by some researchers such as Barabási that the prevalence of small world networks in biological systems may reflect an evolutionary advantage of such an architecture. One possibility is that small-world networks are more robust to perturbations than other network architectures. If this were the case, it would provide an advantage to biological systems that are subject to damage by mutation or viral infection.

In a small world network with a degree distribution following a power-law, deletion of a random node rarely causes a dramatic increase in mean-shortest path length (or a dramatic decrease in the clustering coefficient). This follows from the fact that most shortest paths between nodes flow through hubs, and if a peripheral node is deleted it is unlikely to interfere with passage between other peripheral nodes. As the fraction of peripheral nodes in a small world network is much higher than the fraction of hubs, the probability of deleting an important node is very low. For example, if the small airport in Sun Valley, Idaho was shut down, it would not increase the average number of flights that other passengers traveling in the United States would have to take to arrive at their respective destinations. However, if random deletion of a node hits a hub by chance, the average path length can increase dramatically. This can be observed annually when northern hub airports, such as Chicago's O'Hare airport, are shut down because of snow; many people have to take additional flights.

By contrast, in a random network, in which all nodes have roughly the same number of connections, deleting a random node is likely to increase the mean-shortest path length slightly but significantly for almost any node deleted. In this sense, random networks are vulnerable to random perturbations, whereas small-world networks are robust. However, small-world networks are vulnerable to targeted attack of hubs, whereas random networks cannot be targeted for catastrophic failure.

Appropriately, viruses have evolved to interfere with the activity of hub proteins such as p53, thereby bringing about the massive changes in cellular behavior which are conducive to viral replication. A useful method to analyze network robustness is the percolation theory.

Construction of small-world networks

The main mechanism to construct small-world networks is the Watts–Strogatz mechanism.

Small-world networks can also be introduced with time-delay,[13] which will not only produces fractals but also chaos[14] under the right conditions, or transition to chaos in dynamics networks.[15]

Degree-Diameter graphs are constructed such that the number of neighbors each vertex in the network has is bounded, while the distance from any given vertex in the network to any other vertex (the diameter of the network) is minimized. Constructing such small-world networks is done as part of the effort to find graphs of order close to the Moore bound.

Another way to construct a small world network from scratch is given in Barmpoutis et al.,[16] where a network with very small average distance and very large average clustering is constructed. A fast algorithm of constant complexity is given, along with measurements of the robustness of the resulting graphs. Depending on the application of each network, one can start with one such "ultra small-world" network, and then rewire some edges, or use several small such networks as subgraphs to a larger graph.

Small-world properties can arise naturally in social networks and other real-world systems via the process of dual-phase evolution. This is particularly common where time or spatial constraints limit the addition of connections between vertices The mechanism generally involves periodic shifts between phases, with connections being added during a "global" phase and being reinforced or removed during a "local" phase.

See also: Diffusion-limited aggregation, pattern formation

Applications

Applications to sociology

The advantages to small world networking for social movement groups are their resistance to change due to the filtering apparatus of using highly connected nodes, and its better effectiveness in relaying information while keeping the number of links required to connect a network to a minimum.[17]

The small world network model is directly applicable to affinity group theory represented in sociological arguments by William Finnegan. Affinity groups are social movement groups that are small and semi-independent pledged to a larger goal or function. Though largely unaffiliated at the node level, a few members of high connectivity function as connectivity nodes, linking the different groups through networking. This small world model has proven an extremely effective protest organization tactic against police action.[18] Clay Shirky argues that the larger the social network created through small world networking, the more valuable the nodes of high connectivity within the network.[17] The same can be said for the affinity group model, where the few people within each group connected to outside groups allowed for a large amount of mobilization and adaptation. A practical example of this is small world networking through affinity groups that William Finnegan outlines in reference to the 1999 Seattle WTO protests.

Applications to earth sciences

Many networks studied in geology and geophysics have been shown to have characteristics of small-world networks. Networks defined in fracture systems and porous substances have demonstrated these characteristics.[19] The seismic network in the Southern California region may be a small-world network.[20] The examples above occur on very different spatial scales, demonstrating the scale invariance of the phenomenon in the earth sciences. Climate networks may be regarded as small world networks where the links are of different length scales.[21]

Applications to computing

Small-world networks have been used to estimate the usability of information stored in large databases. The measure is termed the Small World Data Transformation Measure.[22][23] The greater the database links align to a small-world network the more likely a user is going to be able to extract information in the future. This usability typically comes at the cost of the amount of information that can be stored in the same repository.

The Freenet peer-to-peer network has been shown to form a small-world network in simulation,[24] allowing information to be stored and retrieved in a manner that scales efficiency as the network grows.

Small-world neural networks in the brain

Both anatomical connections in the brain[25] and the synchronization networks of cortical neurons[26] exhibit small-world topology.

A small-world network of neurons can exhibit short-term memory. A computer model developed by Solla et al.[27][28] had two stable states, a property (called bistability) thought to be important in memory storage. An activating pulse generated self-sustaining loops of communication activity among the neurons. A second pulse ended this activity. The pulses switched the system between stable states: flow (recording a "memory"), and stasis (holding it).

On a more general level, many large-scale neural networks in the brain, such as the visual system and brain stem, exhibit small-world properties.[5]

Small world with a distribution of link length

The WS model includes a uniform distribution of long-range links. When the distribution of link lengths follows a power law distribution, the mean distance between two sites changes depending on the power of the distribution.[29]

See also

- Barabási–Albert model

- Climate Networks

- Dual-phase evolution

- Dunbar's number

- Erdős number

- Erdős–Rényi (ER) model

- Percolation theory

- Scale-free network

- Six degrees of Kevin Bacon

- Small world experiment

- Social network

- Watts and Strogatz Model

References

- ↑ http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v393/n6684/full/393440a0.html

- ↑ Watts, Duncan J.; Strogatz, Steven H. (June 1998). "Collective dynamics of 'small-world' networks". Nature. 393 (6684): 440–442. Bibcode:1998Natur.393..440W. doi:10.1038/30918. PMID 9623998. Papercore Summary http://www.papercore.org/Watts1998

- ↑ Barthelemy, M.; Amaral, LAN (1999). "Small-world networks: Evidence for a crossover picture". Phys. Rev. Lett. 82 (15): 3180–3183. arXiv:cond-mat/9903108

. Bibcode:1999PhRvL..82.3180B. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.82.3180.

. Bibcode:1999PhRvL..82.3180B. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.82.3180. - ↑ Braunstein, Lidia A.; Buldyrev, Sergey V.; Cohen, Reuven; Havlin, Shlomo; Stanley, H. Eugene (2003). "Optimal Paths in Disordered Complex Networks". Physical Review Letters. 91 (16). Bibcode:2003PhRvL..91p8701B. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.91.168701. ISSN 0031-9007.

- 1 2 The brainstem reticular formation is a small-world, not scale-free, network M. D. Humphries, K. Gurney and T. J. Prescott, Proc. Roy. Soc. B 2006 273, 503–511, doi:10.1098/rspb.2005.3354

- ↑ The ubiquity of small-world networks Q.K. Telesford, K.E. Joyce, S. Hayasaka, J.H. Burdette, P.J. Laurienti, Brain Connect. 2011;1(5):367–75, doi:10.1089/brain.2011.0038

- ↑ Telesford, Joyce, Hayasaka, Burdette, and Laurienti (2011). "The Ubiquity of Small-World Networks". Brain Connectivity. 1 (0038): 367–75. doi:10.1089/brain.2011.0038. PMC 3604768

. PMID 22432451.

. PMID 22432451. - ↑ R. Cohen, S. Havlin, and D. ben-Avraham (2002). "Structural properties of scale free networks". Handbook of graphs and networks. Wiley-VCH, 2002 (Chap. 4).

- ↑ R. Cohen, S. Havlin (2003). "Scale-free networks are ultrasmall". Phys. Rev. Lett. 90 (5): 058701. arXiv:cond-mat/0205476

. Bibcode:2003PhRvL..90e8701C. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.90.058701. PMID 12633404.

. Bibcode:2003PhRvL..90e8701C. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.90.058701. PMID 12633404. - ↑ Bork, P.; Jensen, LJ; von Mering, C.; Ramani, A.; Lee, I.; Marcotte, EM. (2004). "Protein interaction networks from yeast to human" (PDF). Current Opinion in Structural Biology. 14 (3): 292–299. doi:10.1016/j.sbi.2004.05.003. PMID 15193308.

- ↑ Van Noort, V; Snel, B; Huynen, MA. (Mar 2004). "The yeast coexpression network has a small-world, scale-free architecture and can be explained by a simple model". EMBO Rep. 5 (3): 280–4. doi:10.1038/sj.embor.7400090. PMC 1299002

. PMID 14968131.

. PMID 14968131. - ↑ Einstein and Alexander the Great lived 2202 years apart. Assuming an age difference of 70 years between any two connected people in the chain that connects the two, this would necessitate at least 32 connections between Einstein and Alexander the Great.

- ↑ X. S. Yang, Fractals in small-world networks with time-delay, Chaos, Solitons & Fractals, vol. 13, 215–219 (2002)

- ↑ X. S. Yang, Chaos in small-world networks, Phys. Rev. E 63, 046206 (2001)

- ↑ W. Yuan, X. S. Luo, P. Jiang, B. Wang, J. Fang, Transition to chaos in small-world dynamical network

- ↑ D.Barmpoutis and R.M. Murray (2010). "Networks with the Smallest Average Distance and the Largest Average Clustering". arXiv:1007.4031

[q-bio.MN].

[q-bio.MN]. - 1 2 Shirky, Clay. 2008. Here Comes Everybody

- ↑ Finnegan, William "Affinity Groups and the Movement Against Corporate Globalization"

- ↑ X. S. Yang, Small-world networks in geophysics, Geophys. Res. Lett., 28(13), 2549–2552 (2001)

- ↑ A. Jimenez, K. F. Tiampo, and A. M. Posadas, Small-world in a seismic network: the California case, Nonlin. Processes Geophys., 15, 389–395 (2008)

- ↑ Gozolchiani, A.; Havlin, S.; Yamasaki, K. (2011). "Emergence of El Niño as an Autonomous Component in the Climate Network". Physical Review Letters. 107 (14). Bibcode:2011PhRvL.107n8501G. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.107.148501. ISSN 0031-9007.

- ↑ http://mike2.openmethodology.org/wiki/Small_Worlds_Data_Transformation_Measure

- ↑ Hillard, Robert (2010). Information-Driven Business. Wiley. ISBN 978-0-470-62577-4.

- ↑ Sandberg, Oskar. "Searching in a Small World" (PDF).

- ↑ Sporns, Olaf; Chialvo DR; Kaiser M; Hilgetag CC (2004). "Organization, development and function of complex brain networks". Trends Cogn Sci. 8 (9): 418–425. doi:10.1016/j.tics.2004.07.008. PMID 15350243.

- ↑ Yu, Shan; D. Huang; W. Singer; D. Nikolić (2008). "A Small World of Neuronal Synchrony". Cerebral Cortex. 18 (12): 2891–2901. doi:10.1093/cercor/bhn047. PMC 2583154

. PMID 18400792.

. PMID 18400792. - ↑ Cohen, Philip. Small world networks key to memory. New Scientist. 26 May 2004.

- ↑ Sara Solla's Lecture & Slides: Self-Sustained Activity in a Small-World Network of Excitable Neurons

- ↑ D. Li, K. Kosmidis, A. Bunde, S. Havlin (2011). "Dimension of spatially embedded networks". Nature Physics. 7: 481–484. Bibcode:2011NatPh...7..481D. doi:10.1038/nphys1932.

Books

- Buchanan, Mark (2003). Nexus: Small Worlds and the Groundbreaking Theory of Networks. Norton, W. W. & Company, Inc. ISBN 0-393-32442-7.

- Dorogovtsev, S.N. & Mendes, J.F.F. (2003). Evolution of Networks: from biological networks to the Internet and WWW. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-851590-1.

- Watts, D. J. (1999). Small Worlds: The Dynamics of Networks Between Order and Randomness. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-00541-9.

- Fowler, JH. (2005) "Turnout in a Small World," in Alan Zuckerman, ed., Social Logic of Politics, Temple University Press, 269–287

- Reuven Cohen and Shlomo Havlin (2010). Complex Networks: Structure, Robustness and Function. Cambridge University Press.

Journal articles

- Albert, R.; Barabási A.L. (2002). "Statistical mechanics of complex networks". Rev. Mod. Phys. 74: 47–97. arXiv:cond-mat/0106096

. Bibcode:2002RvMP...74...47A. doi:10.1103/RevModPhys.74.47.

. Bibcode:2002RvMP...74...47A. doi:10.1103/RevModPhys.74.47. - Albert, R.; Barabási A.L. (1999). "Emergence of scaling in random networks". Science. 286 (5439): 509–12. arXiv:cond-mat/9910332

. Bibcode:1999Sci...286..509B. doi:10.1126/science.286.5439.509. PMID 10521342.

. Bibcode:1999Sci...286..509B. doi:10.1126/science.286.5439.509. PMID 10521342. - Barthelemy, M.; Amaral, LAN. (1999). "Small-world networks: Evidence for a crossover picture". Phys. Rev. Lett. 82 (15): 3180–3183. arXiv:cond-mat/9903108

. Bibcode:1999PhRvL..82.3180B. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.82.3180.

. Bibcode:1999PhRvL..82.3180B. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.82.3180. - Dorogovtsev, S.N.; Mendes, J.F.F. (2000). "Exactly solvable analogy of small-world networks". Europhys. Lett. 50: 1–7. arXiv:cond-mat/9907445

. Bibcode:2000EL.....50....1D. doi:10.1209/epl/i2000-00227-1.

. Bibcode:2000EL.....50....1D. doi:10.1209/epl/i2000-00227-1. - Milgram, Stanley (1967). "The Small World Problem". Psychology Today. 1 (1): 60–67.

- Newman, Mark (2003). "The Structure and Function of Complex Networks". SIAM Review. 45 (2): 167–256. arXiv:cond-mat/0303516

. Bibcode:2003SIAMR..45..167N. doi:10.1137/S003614450342480. pdf

. Bibcode:2003SIAMR..45..167N. doi:10.1137/S003614450342480. pdf - Ravid, D.; Rafaeli, S. (2004). "Asynchronous discussion groups as Small World and Scale Free Networks". First Monday. 9 (9). doi:10.5210/fm.v9i9.1170.

- R. Parshani, S.V. Buldyrev, S. Havlin (2011). "Critical effect of dependency groups on the function of networks". PNAS. 108: 1007–1010. arXiv:1010.4498

. Bibcode:2011PNAS..108.1007P. doi:10.1073/pnas.1008404108.

. Bibcode:2011PNAS..108.1007P. doi:10.1073/pnas.1008404108. - S. V. Buldyrev, R. Parshani, G. Paul, H. E. Stanley, S. Havlin (2010). "Catastrophic cascade of failures in interdependent networks". Nature. 464 (7291): 1025–8. arXiv:0907.1182

. Bibcode:2010Natur.464.1025B. doi:10.1038/nature08932. PMID 20393559.

. Bibcode:2010Natur.464.1025B. doi:10.1038/nature08932. PMID 20393559.

External links

- Dynamic Proximity Networks by Seth J. Chandler, The Wolfram Demonstrations Project.

- Small-World Networks entry on Scholarpedia (by Mason A. Porter)