Sloth lemur

| Sloth lemur | |

|---|---|

| |

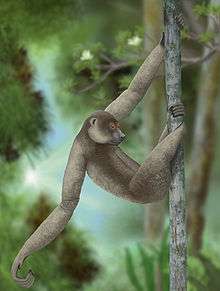

| Life restoration of a large sloth lemur (Palaeopropithecus ingens) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Synapsida |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Primates |

| Suborder: | Strepsirrhini |

| Superfamily: | Lemuroidea |

| Family: | †Palaeopropithecidae Tattersall, 1973[1] |

| Genera | |

The sloth lemurs (Palaeopropithecidae) comprise an extinct clade of lemurs that includes four genera.[2][3] The common name can be misleading, as members of Palaeopropithecidae were not closely related to sloths, but instead to lemurs. This clade has been dubbed the ‘‘sloth lemurs’’ because of remarkable postcranial convergences with South American sloths.[4] Despite postcranial similarities, however, the hands and feet show significant differences. Sloths possess long, curved claws, while sloth lemurs have short, flat nails on their distal phalanges like most primates.[5]

Diet

Members of the Palaeopropithecidae family appear to have eaten a mix of fruit, nuts, and foliage.[6] The sloth lemurs were mixed-feeders rather than specialized browsers who ate a mixed diet based on seasonality. However, on the basis of high robusticity of the mandibular corpus, Palaeopropithecus and Archaeoindris can be considered highly folivorous.[4] The Palaeopropithecidae family exhibited molar megadonty, small deciduous teeth with low occlusal length ratios, and a decoupling of the speed of dental and body growth with acceleration of dental development relative to body growth. These attributes were observed in conjunction with the finding that Palaeopropithecidae experienced prolonged periods of gestation.[7]

Distribution and Diversity

Postcranial measurements and anatomy suggest that three of the four genera, Palaeopropithecus, Babakotia, and Mesopropithecus were primarily arboreal and suspensory.[5] The family was isolated due to river systems which formed a bio-geographical boundary, and likely attributed to the speciation of the family into four genera.[8]

Taxonomy

Traditionally the Palaeopropithecidae family has been considered most closely related to members of the extant family Indriidae based on morphology. Recently, DNA from extinct giant lemurs has confirmed this, as well as the fact that Malagasy primates in general share a common ancestor.[9] The post-canine teeth of sloth lemurs are similar in number (two premolars, three molars) and general design to living Indriids. Babakotia and Mesopropithecus preserve the typical Indriid-like toothcomb, but Palaeopropithecus and Archaeoindris have replaced it with four short and stout teeth of unknown functional significance.[4] The vertebrae formation supports the theory that three of the four genera were suspensory/arboreal, while Babakotia was more likely antipronograde.[10]

Extinction

The extinction of Palaeopropithecus (as well as other giant lemurs) has been linked to climate change and the subsequent collapse of ecosystems that come with rapid climate shift. Recent findings also indicate that human hunting is partly responsible for the extinction of giant lemurs. It is likely not the only cause and cannot be applied to the entire island of Madagascar, but does explain patterns in certain regions of human settlement.[11] Long bones have been discovered with cuts characteristic of butchering, either by dismembering and skinning or by filleting. These marks indicate removal of muscle tissue and dismemberment at joints.[12] Thorough scrutiny has led scientists to believe these marks to be from hunting by early humans.[13]

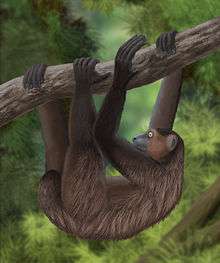

Mesopropithecus globiceps

Mesopropithecus globiceps

| Taxonomy of family Palaeopropithecidae[14](Table 21.1) | Phylogeny of sloth lemurs and their closest relatives[15][16] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

References

- ↑ McKenna, MC; Bell, SK (1997). Classification of Mammals: Above the Species Level. Columbia University Press. p. 335. ISBN 0-231-11013-8.

- ↑ Mittermeier, Russell A.; et al. (2006). Lemurs of Madagascar (2nd ed.). Conservation International. pp. 44–45. ISBN 1-881173-88-7.

- ↑ Nowak, Ronald M. (1999). Walker's Primates of the World. Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 89–91. ISBN 0-8018-6251-5.

- 1 2 3 "Molar microwear of subfossil lemurs: improving the resolution of dietary inferences". J. Hum. Evol. 43: 645–57. November 2002. doi:10.1006/jhev.2002.0592. PMID 12457853.

- 1 2 "Phalangeal Curvature and Positional Behavior in Extinct Sloth Lemurs (Primates, Palaeopropithecidae) on JSTOR". JSTOR 43006.

- ↑ Godfrey, Laurie R.; Semprebon, Gina M.; Jungers, William L.; Sutherland, Michael R.; Simons, Elwyn L.; Solounias, Nikos (2004-09-01). "Dental use wear in extinct lemurs: evidence of diet and niche differentiation". Journal of Human Evolution. 47 (3): 145–169. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2004.06.003. PMID 15337413.

- ↑ "Dental Microstructure and Life History in Subfossil Malagasy Lemurs on JSTOR". JSTOR 3058636.

- ↑ Gommery, Dominique; Tombomiadana, Sabine; Valentin, Frédérique; Ramanivosoa, Beby; Bezoma, Raulin (2004-10-01). "Nouvelle découverte dans le Nord-Ouest de Madagascar et répartition géographique des espèces du genre Palaeopropithecus". Annales de Paléontologie. 90 (4): 279–286. doi:10.1016/j.annpal.2004.07.001.

- ↑ Karanth, K. Praveen; Delefosse, Thomas; Rakotosamimanana, Berthe; Parsons, Thomas J.; Yoder, Anne D.; Simons, Elwyn L. (2005-04-05). "Ancient DNA from Giant Extinct Lemurs Confirms Single Origin of Malagasy Primates". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 102 (14): 5090–5095. doi:10.1073/pnas.0408354102. JSTOR 3375184. PMC 555979

. PMID 15784742.

. PMID 15784742. - ↑ Granatosky, Michael C.; Miller, Charlotte E.; Boyer, Doug M.; Schmitt, Daniel (2014-10-01). "Lumbar vertebral morphology of flying, gliding, and suspensory mammals: Implications for the locomotor behavior of the subfossil lemurs Palaeopropithecus and Babakotia". Journal of Human Evolution. 75: 40–52. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2014.06.011.

- ↑ Muldoon, Kathleen M. (2010-04-01). "Paleoenvironment of Ankilitelo Cave (late Holocene, southwestern Madagascar): implications for the extinction of giant lemurs". Journal of Human Evolution. 58 (4): 338–352. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2010.01.005. PMID 20226497.

- ↑ Godfrey, Laurie R.; Jungers, William L. (2003-01-01). "The extinct sloth lemurs of Madagascar". Evolutionary Anthropology: Issues, News, and Reviews. 12 (6): 252–263. doi:10.1002/evan.10123. ISSN 1520-6505.

- ↑ Perez, Ventura R.; Godfrey, Laurie R.; Nowak-Kemp, Malgosia; Burney, David A.; Ratsimbazafy, Jonah; Vasey, Natalia (2005-12-01). "Evidence of early butchery of giant lemurs in Madagascar". Journal of Human Evolution. 49 (6): 722–742. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2005.08.004. PMID 16225904.

- ↑ Godfrey, L. R.; Jungers, W. L.; Burney, D. A. (2010). "Chapter 21: Subfossil Lemurs of Madagascar". In Werdelin, L.; Sanders, W. J. Cenozoic Mammals of Africa. University of California Press. pp. 351–367. ISBN 978-0-520-25721-4.

- ↑ Orlando, L.; Calvignac, S.; Schnebelen, C.; Douady, C. J.; Godfrey, L. R.; Hänni, C. (2008). "DNA from extinct giant lemurs links archaeolemurids to extant indriids" (PDF). BMC Evolutionary Biology. 8 (121). doi:10.1186/1471-2148-8-121. PMC 2386821

. PMID 18442367.

. PMID 18442367. - ↑ Godfrey, L. R.; Jungers, W. L. (2003). "Subfossil Lemurs". In Goodman, S. M.; Benstead, J. P. The Natural History of Madagascar. University of Chicago Press. pp. 1247–1252. ISBN 0-226-30306-3.